| | | | | | | Presented By the National Pharmaceutical Council | | | | Axios Science | | By Alison Snyder · Oct 27, 2022 | | Thanks for reading Axios Science. This week's newsletter — about ancient trees, trust in scientists, and more — is 1,626 words, a 6.5-minute read. - Send your feedback, ideas and favorite old trees to me at alison@axios.com.

- Please ask your friends and colleagues to sign up here to receive this newsletter.

| | | | | | 🌲 1 big thing: The push to protect ancient trees |  | | | Illustration: Gabriella Turrisi/Axios | | | | Ancient trees contain unique information about Earth's past — the planet's climate, the ebb and flow of civilizations, and the biology of a species' survival — that can be valuable for modeling the planet's future. - As these trees are threatened by people, pests and fire, scientists and historians are increasing calls for their protection.

Why it matters: Ancient trees and the records they carry can't be restored. - "If we lose them, they are gone," says Chuck Cannon, director of the Center for Tree Science at the Morton Arboretum.

- "It is a type of extinction. We lose our connections to past conditions and potential ways in which a forest or tree species can evolve."

Details: Ancient trees are those that are unusually old for their species — "often more than 10 to 20 times older than the average tree in the forest," Cannon and his colleagues wrote in an article published last week in the journal Trends in Ecology and Evolution. - Some can live for centuries. An estimated 25 species, including baobabs (Adansonia digitata) and bristlecone pines (Pinus longaeva), can live for at least 1,000 years without human help.

That's the scientific definition. But ancient trees are also part of what historian Jared Farmer calls elderflora — long-living trees venerated by cultures and even "honored with personhood," he writes in his new book, "Elderflora: A Modern History of Ancient Trees." - Farmer, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, chronicles how trees got caught up in conflict, industrial revolutions and science, and how they've been protected, prodded and pillaged along the way.

- He also traces the birth of tree ring science, or dendrochronology, and the contributions and concerns it raised.

How it works: Old trees support other species of plants and animals, form networks of roots that carry nutrients beneath the forest floor, and influence their own microclimates. - They capture carbon from the air. Trees grow faster later in their life — and bigger trees store more carbon.

- Their rings carry proxy data about temperature, precipitation and disturbances in past climates — information that can help predict how a forest might respond to changes in temperature and other conditions in the future or to model climates to come.

- The unique combination of genetic and epigenetic changes in these "lottery winners," which survive for centuries or more, helps forests adapt and survive, Cannon and his colleagues reported earlier this year in Nature Plants.

- "There is no reason a tree should die from old age — they are always renewing their organs. It is actually a very rare event, almost chance," Cannon says. Other scientists are researching that theory.

Where it stands: Longer warm seasons and air fertilized with CO2 from climate change are spurring the growth of temperate and boreal forests. - But forests are skewing young — between 1900 and 2015, one-third of the world's old-growth forests were lost, according to a 2020 study.

What to watch: The Biden administration earlier this year issued an executive order directing the creation of an inventory of old-growth forests and their conservation. - Cannon and his colleagues are calling for the framework of the Convention on Biological Diversity to include mapping and monitoring old-growth forests and ancient trees. This would include working with Indigenous people and remote communities to better understand ancient trees.

The big picture: Farmer, as a historian, views long-lived trees — and the stories of and in them — as a way to think long-term. - "To me, the proper understanding of humans' place on the planet acknowledges not just the precedence of Earth for humanity, but the precedence on Earth of so many other kinds of life forms [that] have successfully adapted to a changing planet over a timescale that is barely within our realm of understanding," he says.

- "Could we learn to live on the planet a fraction of the time that some of these ancient conifers have? That's a great species-level goal, right?

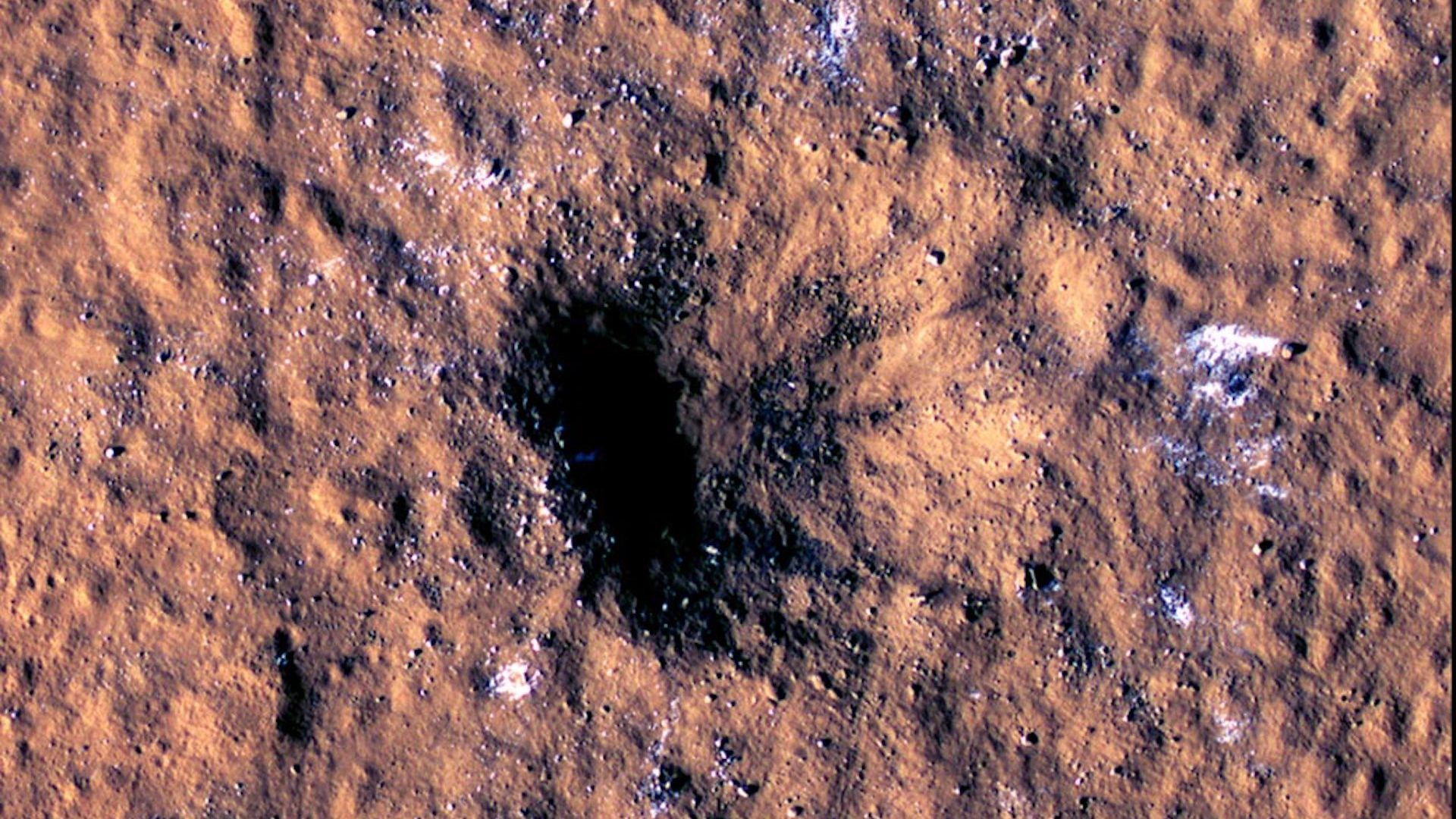

Go deeper. |     | | | | | | 2. Spacecraft feel, see major impact on Mars |  | | | A meteor impact seen on Mars. Photo: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona | | | | A NASA lander on Mars felt the shockwaves from a major meteor strike on the Red Planet, according to new studies published today, Axios' Miriam Kramer writes. Why it matters: The InSight lander's observations are allowing scientists to understand and map the interior and crust of Mars with great detail, potentially revealing more about how the world and even its atmosphere may have formed. Driving the news: InSight felt a magnitude 4 marsquake caused by a meteor strike on Christmas Eve last year, according to two new studies in the journal Science. - Some of the waves caused by this meteor strike — called surface waves — hadn't been seen by InSight before, but they are particularly useful when trying to map the crust of the planet.

- "The whole path between the event — in this case the impact — and InSight is sampled by the surface waves as they move across the planet," Bruce Banerdt, InSight's principal investigator, said during a press conference Thursday. "And so we have an idea of what the crust is over this fairly long path."

- The impact occurred more than 2,000 miles away from InSight.

Context: Another study published in Nature Astronomy this week found magma may still flow beneath the surface of at least one part of Mars, causing marsquakes. The intrigue: NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter also later caught sight of the impact crater the meteor created. The strike flung material up to 23 miles away, according to NASA, and even uncovered ice in the process. - "The image of the impact was unlike any I had seen before, with the massive crater, the exposed ice, and the dramatic blast zone preserved in the Martian dust," Liliya Posiolova, who works with the MRO, said in a statement.

What to watch: InSight is nearing the end of its life on Mars after landing on the Red Planet in 2018. - The spacecraft is being covered with Martian dust that has settled atop its solar panels, preventing it from drawing the power it needs.

- NASA expects the probe will no longer be able to function in about six weeks, ending its mission.

|     | | | | | | 3. In scientists we do — and don't — trust |  Data: Pew Research Center; Chart: Axios Visuals Democrats and Republicans disagree on the role of scientists in public policy — and that divide has only grown wider since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a new survey from the Pew Research Center, Axios' Herb Scribner writes. By the numbers: The share of Americans who say scientists are usually better than others at making policy decisions about scientific issues dropped from 45% in 2019 to 41% in September 2022, per Pew. - In the beginning of the pandemic (May 2020), 47% of Americans said scientific experts were better than others at making policy decisions, and 60% said scientists should play an active role in policy debates about scientific issues.

- In the latest survey, 48% of Americans responded that scientific experts should play an active role in policy. Drops were seen among both Republicans and Democrats.

Between the lines: Democrats have higher trust in scientists than Republicans, per the new Pew data. - 41% of Democrats and those who lean toward the Democratic Party have a great deal of confidence in scientists. Nearly all (89%) have at least a fair amount of confidence. About one in 10 Democrats have a negative view of scientists.

- 15% of Republicans and Republican leaners have a strong level of confidence in scientists when it comes to the public arena. About 36% have little or no confidence in scientists.

- A majority (63%) of Republicans did have a fair amount of confidence in scientists to act in the best interests of the public.

The big picture: Democrats and Republicans have been "at odds over science-related questions" during the pandemic, especially when it comes to the coronavirus threat, public policy response, mask-wearing and vaccines, according to Pew. - What role scientific expertise should play in policymaking is a longstanding question that reared its head during the COVID pandemic and remains a relevant one in the face of climate change and other complex challenges.

Methodology: Figures in the story come from a new Pew Research Center survey that was conducted from Sept. 13 to 18, 2022. About 10,000 panelists responded out of 11,687 who were sampled. |     | | | | | | A message from the National Pharmaceutical Council | | 340B: Where is the money going? | | |  | | | | It's the fundamental question health policy researchers should be asking about 340B. Transparency requirements would provide the needed oversight and accountability for this program. It's time for an honest conversation about 340B. | | | | | | 4. Worthy of your time | | A new treatment for debilitating nightmares offers sweeter dreams (Jackie Rocheleau — Science News) It takes a lot of elephant brains to solve this mystery (Jack Tamisiea — NYT) Everything dies, including information (Erik Sherman — MIT Tech Review) |     | | | | | | 5. Something wondrous |  | | | Honey bees swarming. Photo: Tim Graham/Getty Images | | | | A swarm of bees can generate an electric field in the atmosphere on par with that produced by thunderstorm clouds, according to a new study. The big picture: Electric fields in Earth's atmosphere play a role in a host of processes, from moving aerosols to directing insects as they forage and pollinate. What they found: Honeybee swarms are made up of thousands of insects, each with their own electric charge created as their wings flap against the air. - When swarms moved over a monitor on the ground, the researchers measured changes in the electric charge in the atmosphere between 100 to 1,000 volts per meter, they report in the journal iScience. The charge was greater when the swarm was denser.

- They then modeled the electrical effect of other species, including desert locusts. They estimate massive locust swarms can alter the atmosphere's electric field even more than honeybees.

The intrigue: "We only recently discovered that biology and static electric fields are intimately linked and that there are many unsuspected links that can exist over different spatial scales, ranging from microbes in the soil and plant-pollinator interactions to insect swarms and the global electric circuit," Ellard Hunting, of the University of Bristol in the UK and one of the study authors, told Popular Science. - "The true implications of this remain speculative, and whether these dynamics induced by insects affect weather is definitely worth investigating."

|     | | | | | | A message from the National Pharmaceutical Council | | 340B: Is it really serving patients? | | |  | | | | Even after 30 years, we don't know if 340B works to improve patient access to medicines. What you need to know: Studying the effects of 340B is difficult because simple transparency requirements don't exist. It's time for an honest conversation about 340B. | | | | Thanks to Laurin-Whitney Gottbrath for editing this newsletter, to the Axios Visuals team, and to Nick Aspinwall for copy editing this edition. |  | | Are you a fan of this email format? It's called Smart Brevity®. Over 300 orgs use it — in a tool called Axios HQ — to drive productivity with clearer workplace communications. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters. If you're interested in advertising, learn more here.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment