| | | | | | | Presented By University of Central Florida | | | | Axios Science | | By Alison Snyder · Jun 02, 2022 | | Thanks for reading Axios Science. This week's edition is 1,575 words, about a 6-minute read. | | | | | | 1 big thing: How to make space for species |  | | | Illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios | | | | The plummet in the planet's biodiversity could be slowed by protecting and expanding key areas animals inhabit and connecting them so species can move freely. Two studies published today lay out ways to make that space. The big picture: There's wide acknowledgment the future of Earth's biodiversity — which supports the health and well-being of the species H. sapiens — hinges on protecting more of the planet. But how much land should be conserved — and where — is debated by scientists, governments, businesses and organizations. Where it stands: Today, 16.6% of Earth's land and inland water ecosystems are protected, per one 2020 estimate. - The draft targets that will be discussed at the 2022 UN Biodiversity Conference (COP15) later this year include protecting 30% of land and seas around the world by 2030 and reducing the rate of extinctions by 90% by 2050.

- It also prioritizes connecting protected lands so animals can move to mate and adapt to changes in their environment.

What's new: Combining data about existing protected areas, land that hasn't been disturbed and the geographical distribution of more than 35,000 species, a new estimate concludes at least 44% of Earth's land — about 25 million square miles — needs more protection to stop the loss of today's biodiversity. - About 70% of this area is currently protected or intact but farming, mining and other intensive uses are imminent threats, especially in countries with developing economies, according to a study published today in the journal Science.

- An additional 4.8 million square miles of land would need to be conserved to meet the biodiversity targets.

Context: The study is one of many global priority maps with varying estimates for how much land should be conserved, which depend in part on the data and specific objectives, says Megan Evans, who studies environmental policy at the University of New South Wales in Australia and wasn't involved in the research. - She has questioned the value of global priority maps given conservation decisions are largely made on the ground but others say both global and local level studies are important because ecology happens across scales.

A second study looks at another part of the conservation equation: connectivity between areas. - Researchers used data about mammal movements and how humans use different areas of land to predict where there would be concentrated flows of medium and large mammals.

- They found areas — especially in eastern Europe and Africa — that could be conserved to connect existing protected land.

- Many of those areas are near places heavily used by humans, creating "pinch points," says Angela Brennan, a conservation scientist at the University of British Columbia and a World Wildlife Fund fellow who is a co-author of the study. That suggests "mitigating the human footprint may improve connectivity more than adding new [protected areas], although both strategies together maximize benefits," the team wrote today in Science.

But, but, but ... Approximately 1.8 billion people live in areas that would need to be conserved to achieve conservation goals, the researchers of the first study report. - "So the potential impacts if these schemes go wrong is enormous," says Chris Sandbrook, a conservation social scientist at the University of Cambridge and a co-author of the study.

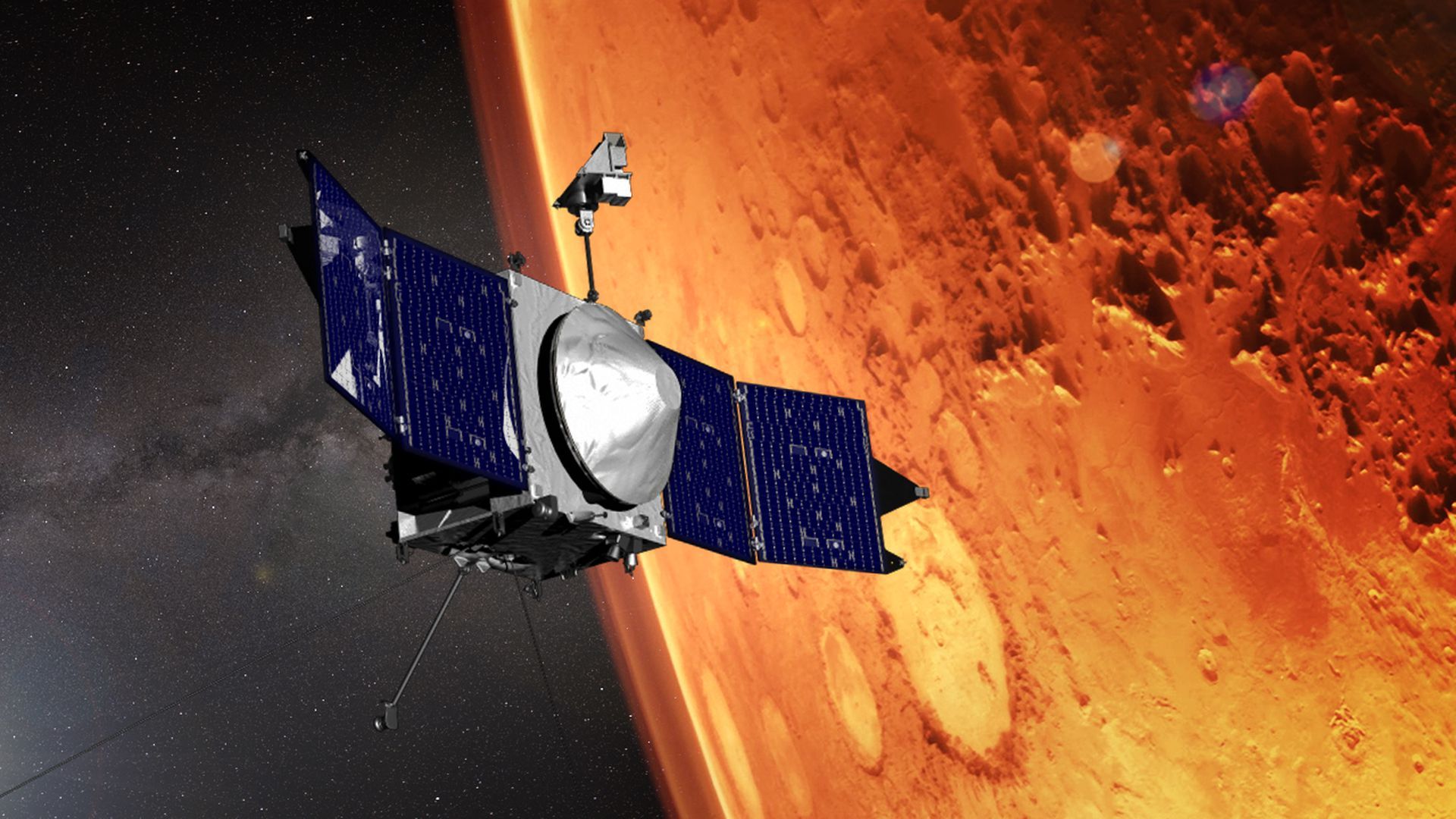

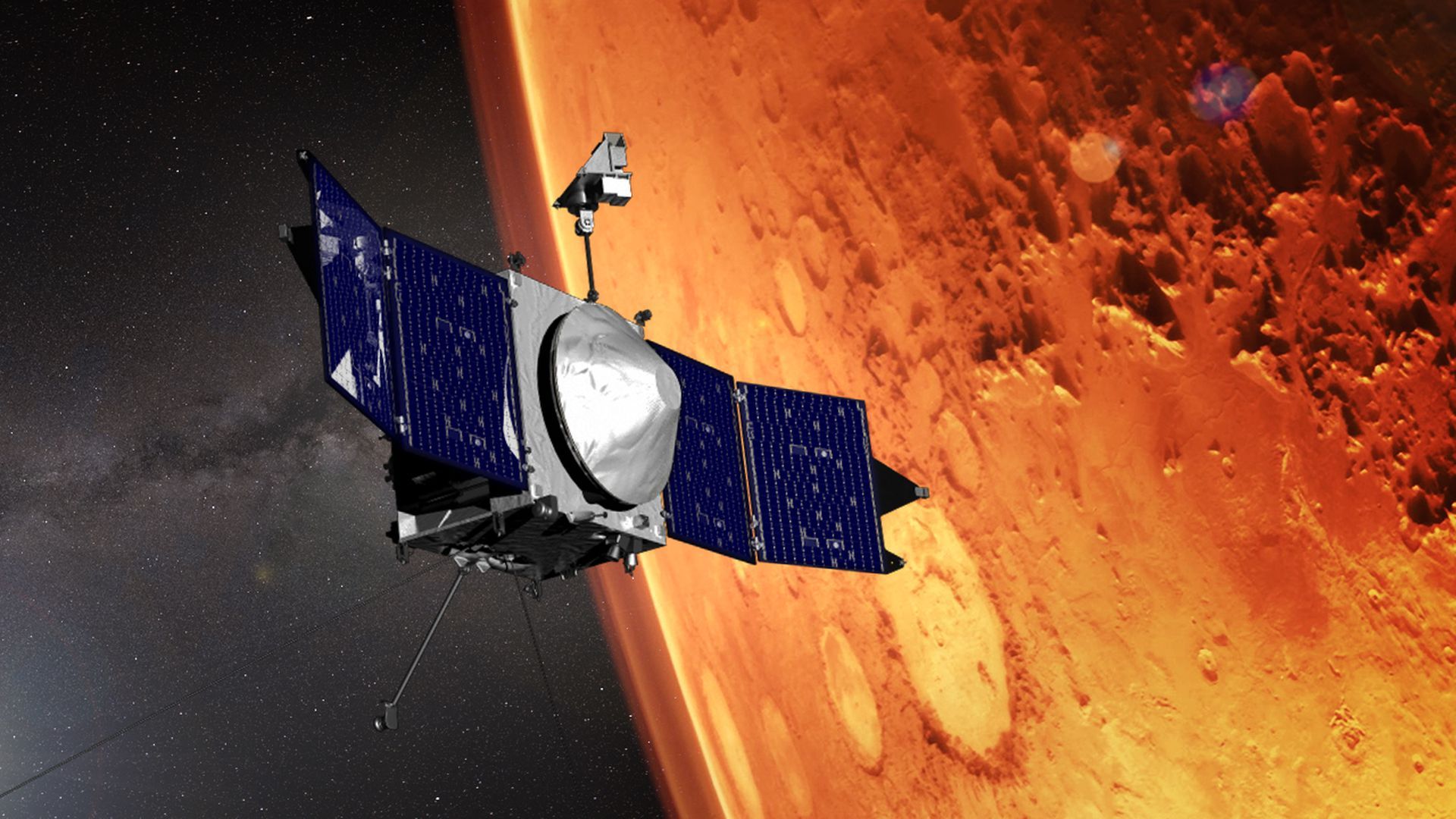

Go deeper. |     | | | | | | 2. NASA Mars orbiter faced "existential threat" |  | | | Artist's representation of MAVEN orbiting Mars. Photo: NASA | | | | A NASA probe tasked with studying Mars from orbit is back to performing its science after a major problem kept it sidelined for months, Axios' Miriam Kramer writes. Why it matters: The MAVEN spacecraft has been orbiting Mars since 2014, and in that time, revealed the key role powerful solar winds played in turning Mars from a wet, relatively warm world into the cold, dry one it is today. - The spacecraft has also been a relay station for communications between NASA's spacecraft on the surface of the planet and Earth.

What's happening: In February, MAVEN started having problems with navigational instruments called Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) designed to help make sure the spacecraft is pointed in the right direction. - MAVEN cycled its computer to try to reboot itself and bring the IMUs back into service. When that didn't work, the spacecraft switched to its backup computer, which allowed mission managers to get better readings from IMU-2.

- Controllers on the ground then got to work implementing a navigational system to allow MAVEN to figure out how to keep itself pointed in the right direction.

- The team was originally going to move to that system later this year anyway, but had to speed up the development to keep the spacecraft functioning.

The intrigue: "The team really stepped up to an existential threat," Rich Burns, the MAVEN project manager at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, said in a statement. - According to a report from Space.com, the team came perilously close to losing MAVEN.

- While they were attempting to get MAVEN functioning again, the spacecraft was drifting, losing its focus on the Sun, which could have ended the mission had they not gotten an IMU back online just in time, Meghan Bartels reported.

- But even once they shifted the spacecraft into a safe configuration, that wasn't the end of the drama. MAVEN wasn't able to act as a communications relay from Mars to Earth during its downtime, decreasing the amount of science coming from the Red Planet as a whole, Bartels added.

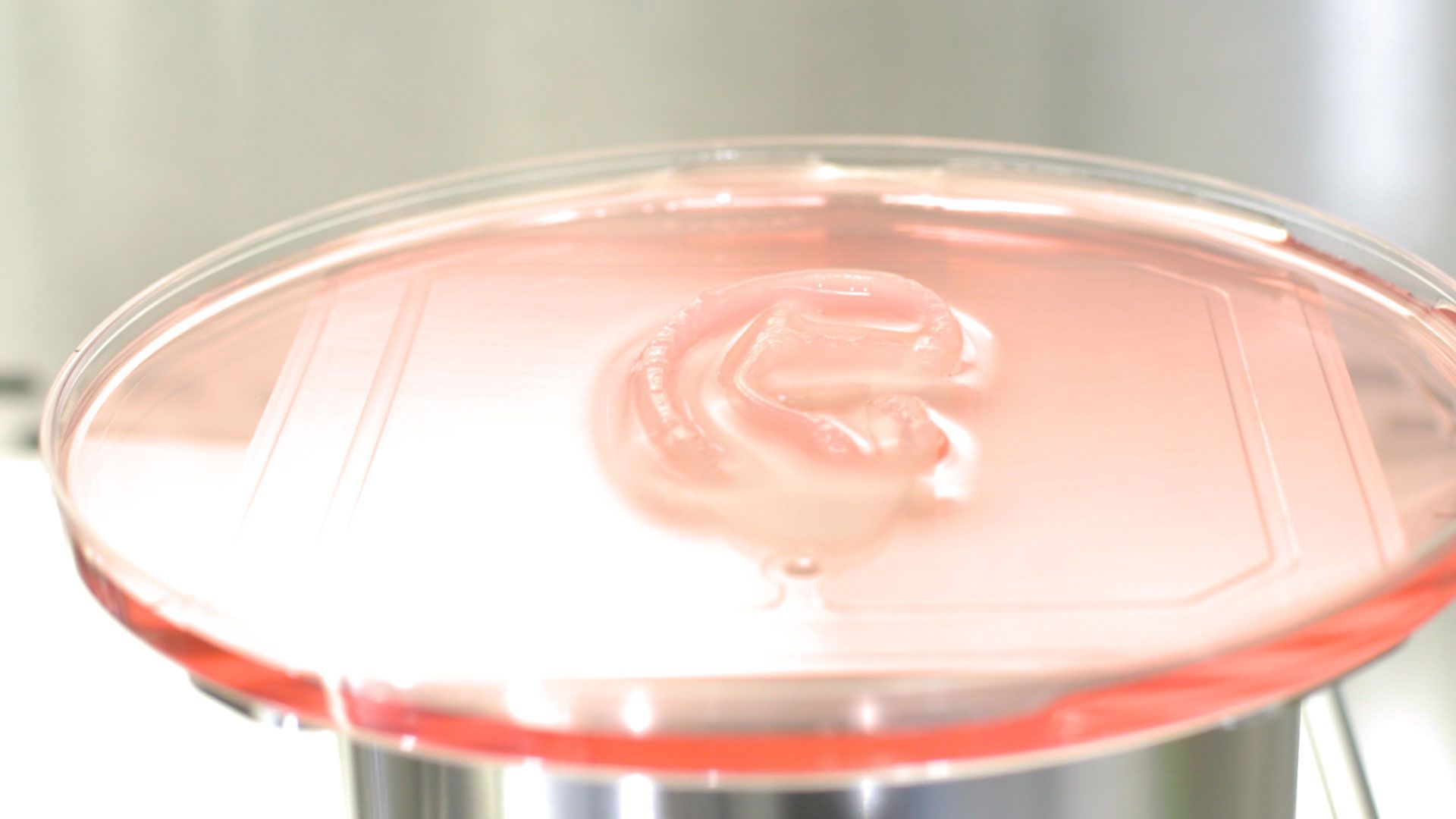

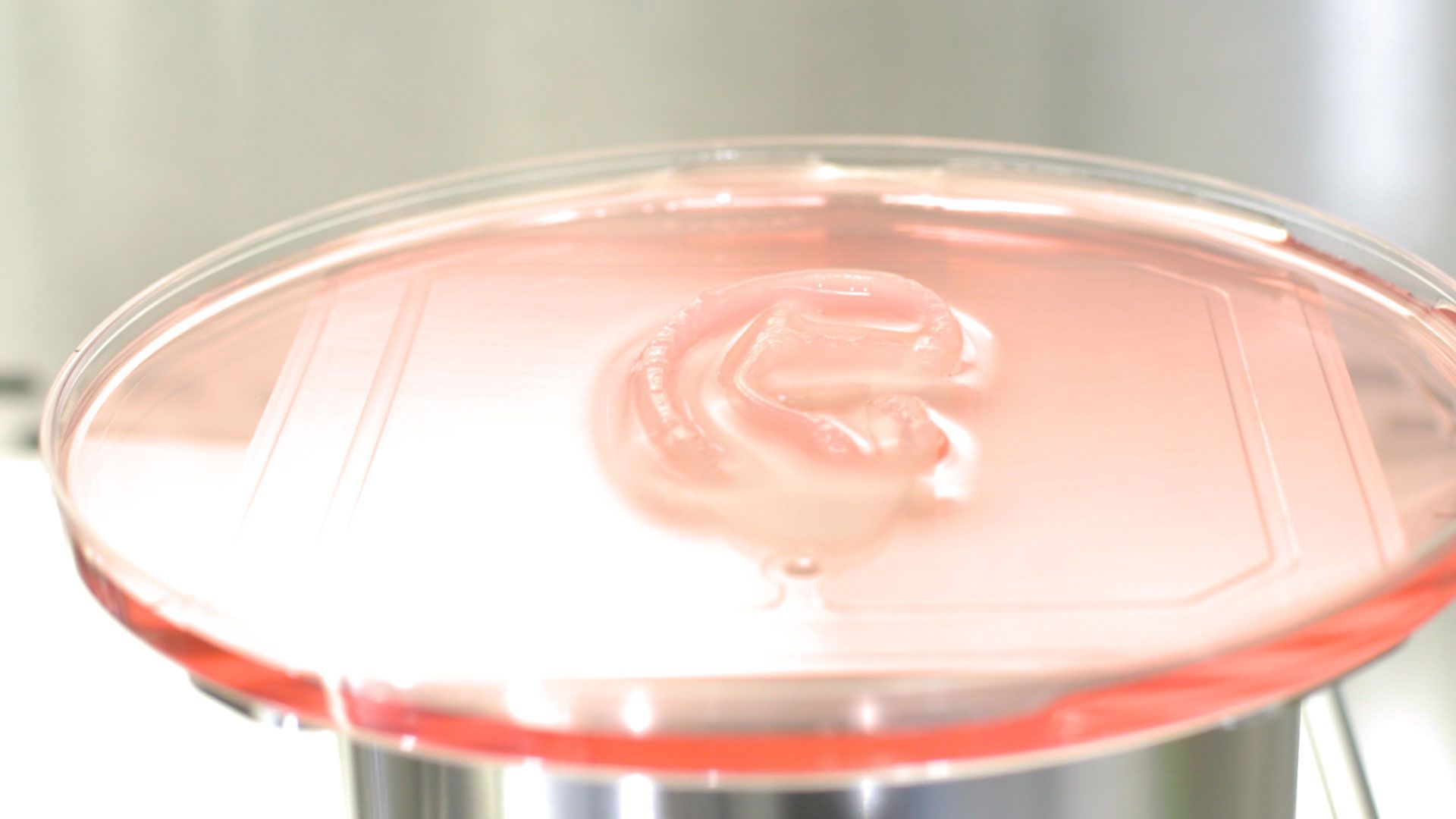

What's next: MAVEN is now back to full science operations and embarking on a freshly extended mission that will see it continuing to study how the Sun's activity affects the Martian atmosphere. |     | | | | | | 3. Catch up quick on COVID |  Data: N.Y. Times; Note: Case counts may be affected by Memorial Day disruptions to reporting; Cartogram: Kavya Beheraj/Axios "The number of reported new COVID cases — along with COVID deaths — appeared to level off over the past seven days," with the caveat that it is unclear if Memorial Day disrupted data reporting, per Axios' Tina Reed and Kavya Beheraj. "New variants appear to be even more immune-resistant than the original Omicron strain, raising the possibility that even retooled vaccines could be outdated by the time they become available this fall," Axios' Caitlin Owens reports. Novavax's application for emergency use authorization of its COVID vaccine — which is based on a protein from the virus rather than mRNA and can be stored at room temperature — will be reviewed by an FDA advisory committee next week, per Axios' Tina Reed. A wave of Omicron subvariant infections hit South Africa even though most people in the country have antibodies, Livia Albeck-Ripka reports in the NYT. "The researchers say the study provides yet more evidence of the capacity of the virus to evolve and dodge immunity." |     | | | | | | A message from University of Central Florida | | Critical engineering talent to keep the nation's grid evolving | | |  | | | | GE Digital and Florida Power & Light are investing in a cutting-edge Microgrid Control Lab at the University of Central Florida. The deets: The lab simulates a control room where students and faculty can gain real-life experiences, developing skills to enhance the U.S. energy grid for the future. | | | | | | 4. First 3D printed ear made with human cells transplanted |  | | | 3DBio Therapeutics says the company has completed its "first-in-human" implant in a clinical trial. Photo: 3DBio Therapeutics | | | | The first 3D printed ear implant has been successfully transplanted on a 20-year-old woman as part of an ongoing clinical trial, Axios' Kelly Tyko writes. Driving the news: 3DBio Therapeutics and the Microtia-Congenital Ear Deformity Institute announced today that they conducted the human ear reconstruction using a living tissue ear implant. Why it matters: Microtia, a rare congenital deformity where one or both outer ears are absent or underdeveloped, affects approximately 1,500 babies born in the U.S. annually. - The new ear was printed in a shape that matches the woman's left ear, according to 3DBio, a regenerative medicine company based in Queens, New York.

- AuriNovo, the name of the implant, is designed to provide a "treatment alternative to rib cartilage grafts and synthetic materials traditionally used to reconstruct the outer ear of microtia patients," the company said.

What they're saying: The successful application of the technology is considered a major advance in the field of tissue engineering, experts told the New York Times. - "It shows this technology is not an 'if' anymore, but a 'when,'" Adam Feinberg, a professor of biomedical engineering at Carnegie Mellon University, who is not affiliated with 3DBio, told the Times.

- However, the company has not released technical details about the process, the Times notes, making peer evaluation of the science difficult.

What's next: A clinical trial is being conducted in Los Angeles, California, and San Antonio, Texas, and expects to enroll 11 patients. - Daniel Cohen, 3DBio CEO and co-founder, said initial indications focus on "cartilage in the reconstructive and orthopedic fields including treating complex nasal defects and spinal degeneration."

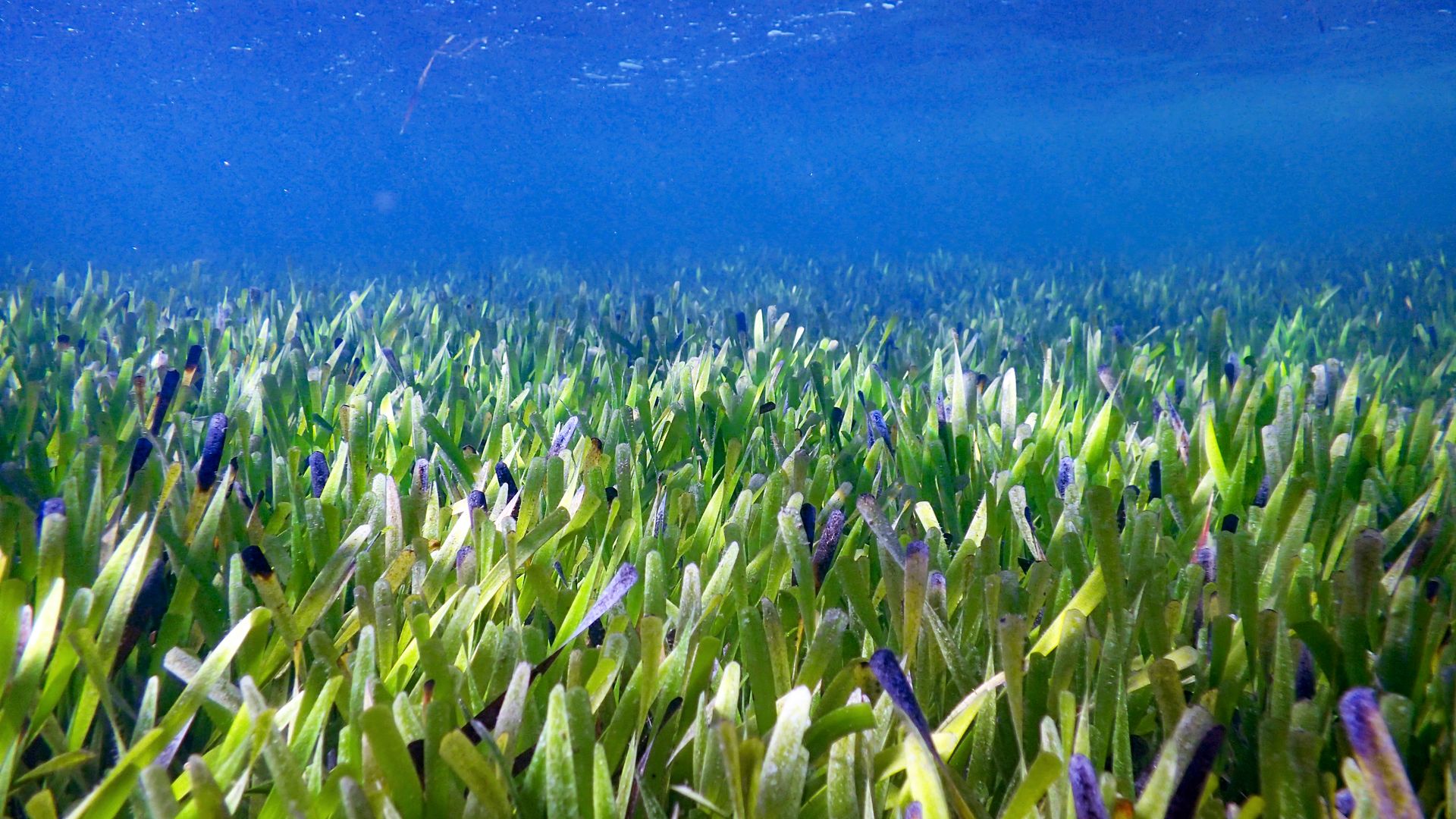

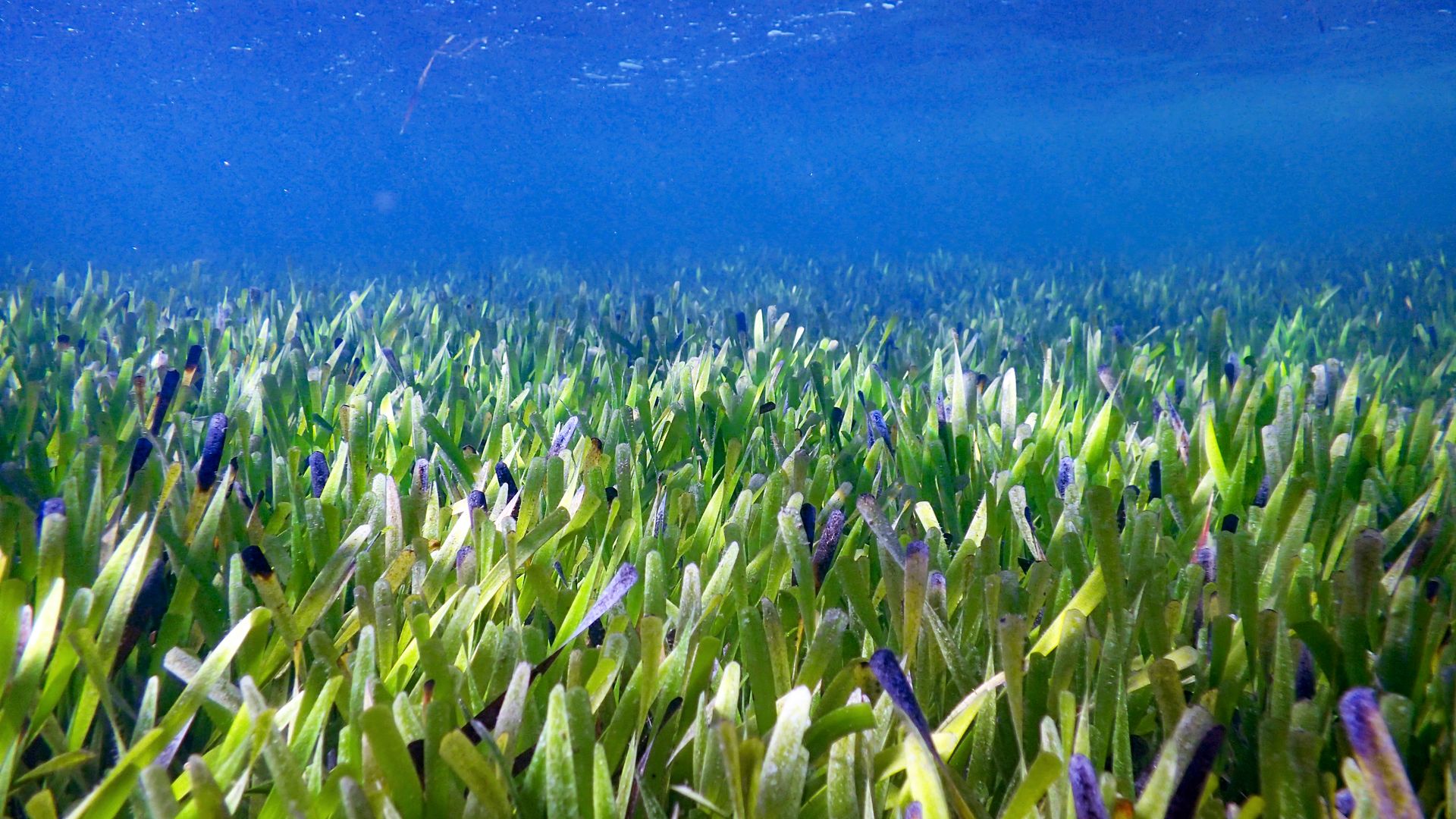

|     | | | | | | 5. Worthy of your time | | Animal divorce: When and why pairs break up (Catherine Offord — The Scientist, subscription) What really happens when Mercury is in retrograde (Marina Koren — The Atlantic, subscription) Guardians of the brain (Diana Kwon — Nature) |     | | | | | | 6. Something wondrous |  | | | Shark Bay seagrass, Posidonia australis. Photo: Rachel Austin/UWA | | | | A seagrass meadow spanning more than 111 miles in western Australia is a single plant — and the world's largest known organism, according to a study published this week. The big picture: "Nature is amazing if you don't disturb it," says Elizabeth Sinclair, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Western Australia and a co-author of the study published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B. Details: DNA analysis revealed the meadow in Shark Bay was a single plant made from clones that grow from rhizomes, a type of stem that extends in the sand in multiple directions. - It takes up about 77 square miles and the researchers estimate it is 4,500 years old.

The intrigue: Normally, seagrass (P. australis) commonly found in the region has 20 chromosomes, but the large clone has 40 chromosomes. - "That effectively doubles the amount of [genetic] variation," Sinclair says. "Having all this extra variation likely gives it an advantage to coping with a wider range in environments including the large change in salinity, or saltiness, of the water."

What's next: The team is now looking at how different pieces of the plant can live in different local environments with varying amounts of salt, Sinclair says. |     | | | | | | A message from University of Central Florida | | Providing talent for energy grid sustainability and innovation | | |  | | | | UCF's Microgrid Control Lab enables students and faculty to test real-life grid control operations and develop skills to optimize, sustain and secure the U.S. energy grid. GE Digital, Florida Power & Light and UCF are investing in engineers to improve how energy is transmitted and delivered. Learn more. | | | | Thanks to Miriam and Kelly for contributing to this week's newsletter and to Laurin-Whitney Gottbrath and Carolyn DiPaolo for editing it. |  | It's called Smart Brevity®. Over 200 orgs use it — in a tool called Axios HQ — to drive productivity with clearer workplace communications. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters. If you're interested in advertising, learn more here.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1300, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment