| | | | | | | Presented By Babbel | | | | Axios Science | | By Alison Snyder ·Jan 14, 2021 | | Thanks for reading Axios Science. This week's newsletter — about science's role in policy, what happens in the brain when we disagree and an advance in treating addiction — is about a 5½-minute read. | | | | | | 1 big thing: Scrutinizing pandemic science advice |  | | | Illustration: Brendan Lynch/Axios | | | | The pandemic is a high-stakes, real-time test of how science informs policy, and the first assessments of how decision-makers have tapped scientists for guidance are now emerging. Why it matters: How democracies use scientific expertise is — and will be — a key question as countries navigate increasingly complex challenges like future pandemics, climate change, AI and whatever else the 21st century throws at us. Driving the news: The U.K.'s House of Commons last week released a report about how the government "has obtained and made use of scientific advice during the pandemic." - The U.K. government crafted pandemic response measures with scientific advice from the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE), a mechanism set up in 2009 for bringing independent experts together to provide scientific and technical advice to policymakers during emergencies.

- But outside of SAGE, advice from experts in social sciences, economics and other fields was also considered. The assessment of this input was "less visible" and its "role in decision-making opaque," the report concluded, emphasizing the need for transparency about who is providing the advice, the evidence they use, and the uncertainties surrounding it.

The report points to the need for advisory groups to include a broad range of expertise that goes beyond science, says Roger Pielke Jr. of the University of Colorado, Boulder, who is evaluating science advice in the pandemic. - "Science advice is often narrowed extremely," says Jessica Weinkle, an assistant professor at the University of North Carolina, Wilmington who is studying the interface of science and policy in the state's pandemic response.

- "Not only does that create embedded problems for diversity of thought and representation but also diversity in what matters and the way we think about relevant information for making decisions."

The big picture: How exactly scientists and experts should inform policymaking is a long-standing question. - We want science to play a prominent role in informing decisions," says Pielke.

- But 'following the science' may not ask enough of both scientists and politicians. "It misplaces accountability, artificially limits the types of expertise you would take and deemphasizes the role of choice."

- Instead, "politicians have to lead experts to provide them with information they need to make better decisions" and experts have to be sure policymakers tell them the decision they're trying to make, he says.

- Ultimately, policy decisions — including those involving science — are political ones, with uncertainties and values. "By giving [policymakers] options, it holds them accountable for the decisions they make," says Weinkle.

What's next: President-elect Biden, who has said he will "follow the science," will inherit a deeply divided U.S. where trust in institutions like the CDC has eroded as the country struggles through a raging pandemic and climate change bears down. - Accountability on the part of policymakers will be key against that backdrop, experts say.

- "If you have divisive politics, you cannot use appeals to expertise to paper over the uncertainties and the variety of possible options that you can consider by saying experts tell us to do this or do that," says Daniel Sarewitz, a professor of science and society at Arizona State University.

- "The best you can do is be clear about uncertainties and why you are making the decision you are making and hope you can build confidence around those."

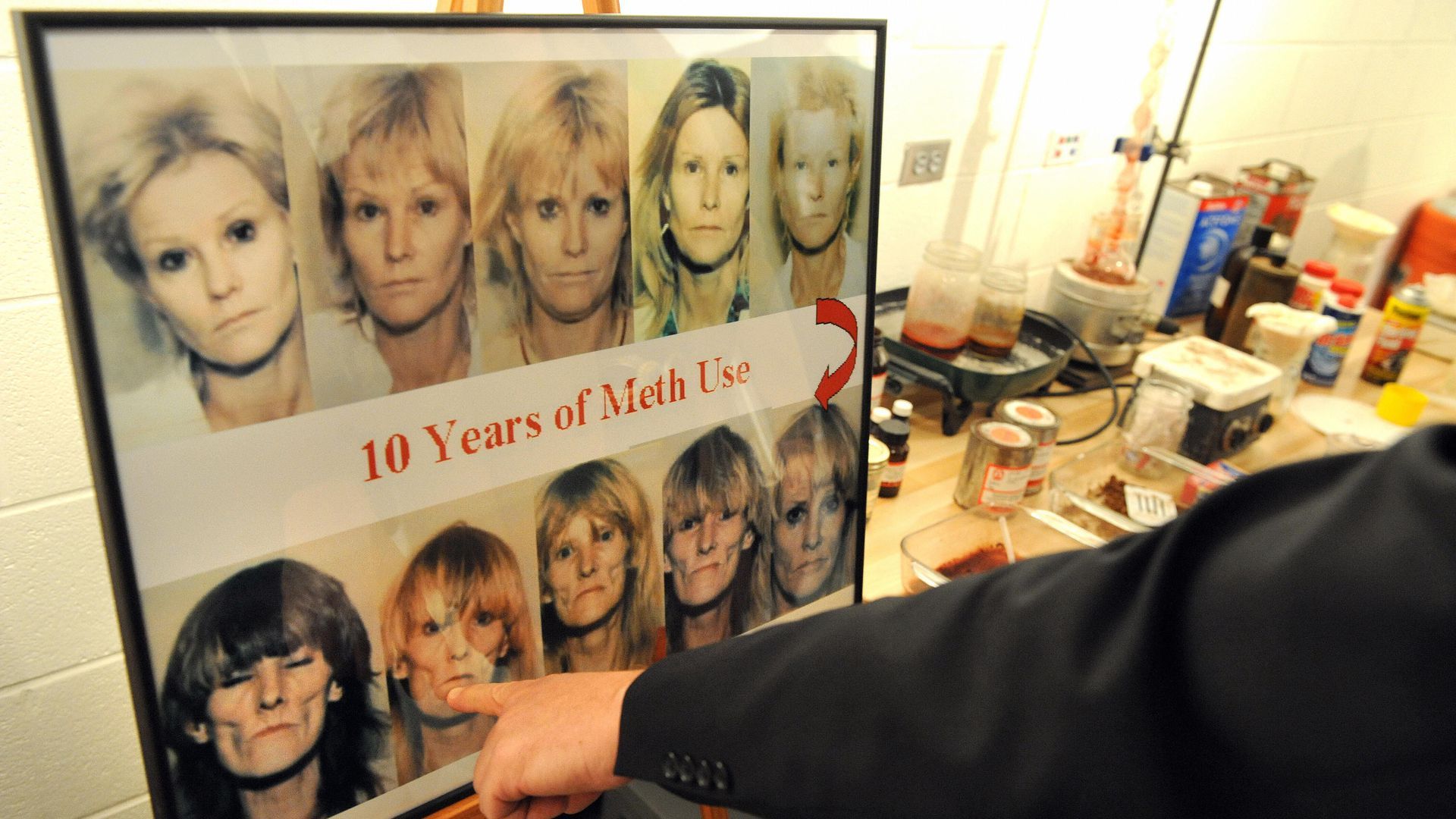

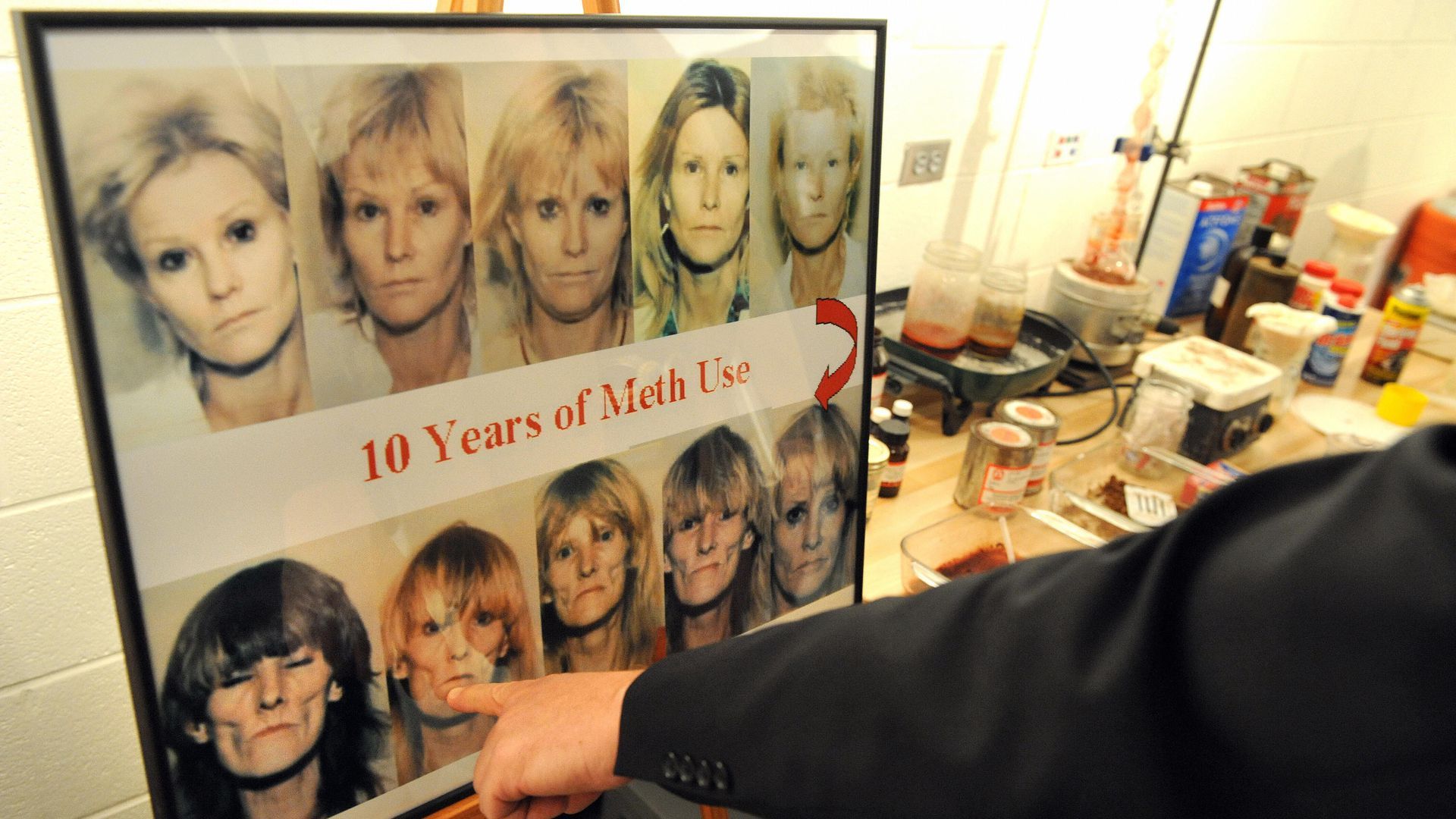

Read the entire story. |     | | | | | | 2. Catch up quick on COVID-19 |  Data: The COVID Tracking Project, state health departments; Map: Andrew Witherspoon/Axios "The U.S. is now averaging nearly 250,000 new coronavirus cases per day — a crisis of staggering proportions, even though many Americans have tuned it out," Axios' Sam Baker and Andrew Witherspoon write. "We're beginning to see more than 4,000 coronavirus deaths a day, Axios' Caitlin Owens reports. Hospitals remain overwhelmed, and the quality of care is being threatened, she writes. A WHO team arrived in China to investigate the origins of SARS-CoV-2 as the country is seeing its biggest rise in cases since last summer. Reinfection from SARS-CoV-2 was rare in a study of more than 20,000 health care workers in the U.K., Nature News' Heidi Ledford reports. Past infection reduced "the risk of catching the virus again by 83% for at least five months." Go deeper: See the state by state results on an interactive graphic |     | | | | | | 3. New drug combo may help people fight meth addiction |  | | | A progressive series of mug shots shows the effects of 10 years of meth use, shown at the DEA Training Academy in 2008. Photo: Tim Sloan/AFP via Getty Images | | | | Combining two FDA-approved drugs may help stop some people's use of methamphetamine, a new study shows. Why it matters: Currently there are no FDA-approved drug treatments available for people with a methamphetamine use disorder — an addiction that has risen during the pandemic, Axios' Eileen Drage O'Reilly writes. - Preliminary CDC data shows overdose deaths from meth and similar stimulants increased 35% during the pandemic.

"This is very timely and urgent because we currently have no medications that can be utilized to help in the treatment of people who are addicted to methamphetamines, and this is the largest effect that we have seen in terms of the therapeutic benefit for any intervention used to improve outcomes on patients with methamphetamine use disorder." — Nora Volkow, of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, tells Axios What's new: In a phase III clinical trial of 403 people with moderate to severe meth addiction (using the drug an average of 27 times per month), researchers gave the non-placebo groups a combination of extended-release naltrexone, used to treat opioid and alcohol use disorders, and bupropion, which is an antidepressant and nicotine cessation aid. - Published in the New England Journal of Medicine Wednesday, the study found that at weeks 5 and 6, 16.5% of those given the combination drug responded, compared to only 3.4% of those in the control group. At weeks 11 and 12, 11.4% of the treatment group responded, compared to 1.8% of the control group.

- "This combination is almost six times better than placebo," says Madhukar H. Trivedi, lead author and chief of the mood disorders division at UT Southwestern Medical Center.

- Participants who took the drug also tended to report fewer cravings and no significant adverse side effects, he says.

- "This significantly increased the likelihood of people being able to stop taking methamphetamine," Volkow tells Axios.

SAMHSA's National Helpline is a free, confidential, 24/7, 365-day-a-year treatment referral and information service for individuals and families facing mental and/or substance use disorders. Call 1-800-662-HELP. Read the entire story. |     | | | | | | A message from Babbel | | Start speaking a new language in three weeks | | |  | | | | In 2021, let language take you places with Babbel. The background: This language learning app gives you bite-sized, manageable lessons in a variety of languages. It'll have you speaking the basics in three weeks. Sign up today and get 60% off. | | | | | | 4. The brain biology of agreeing — and disagreeing |  | | | Illustration: Annelise Capossela/Axios | | | | Agreeing and disagreeing recruit different regions of the brain when two people debate, according to new research. The big picture: Our interactions and conversations are among our most consequential behaviors, particularly in politically divisive times, yet little is known about the neurobiology of what happens in the brains of two people as they interact. Details: Neuroscientist Joy Hirsch of Yale University and her colleagues paired 38 adults in face-to-face discussions and looked at how the activity of neurons changed as the people discussed controversial statements (for example, "marijuana should be legalized") that they either agreed or disagreed on. - Cognitive processes were more engaged during disagreement, whereas sensory areas (for example, those involved in eye movement, gesturing and social cues) were more engaged during agreement, they report this week in the journal Frontiers in Human Neuroscience.

- The brain isn't working hard when agreeing, says Hirsch.

- But, "in disagreement, the brain is massively engaged in cognitive tasks."

And during disagreement, the signals in the brains of both people are less in sync with each other compared to when two people are in agreement, the researchers found. - "Synchronous engagement happens during moments of simpatico, gesturing, and smiling. Those things are creating coherence of brains," says Hirsch.

How they did it: The researchers measured the activity of neurons using function near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), a technique similar to fMRI in that it measures blood flow to neurons, a proxy for their activation. - Unlike fMRI, the technique can be used to image multiple people simultaneously and they can freely move and gesture.

- Yes, but: It can't detect changes in regions deeper in the brain, where the network's underlying emotions exist.

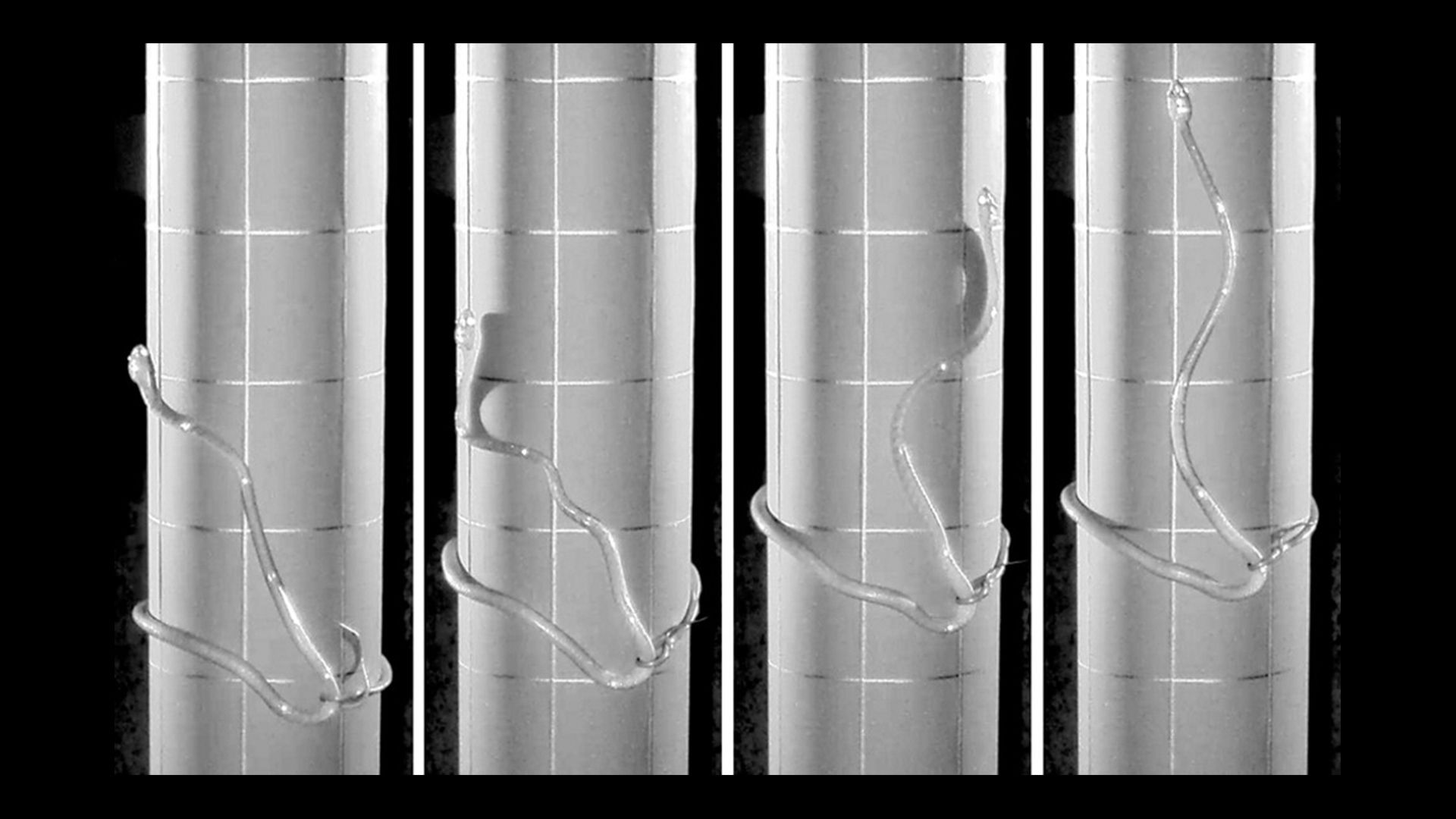

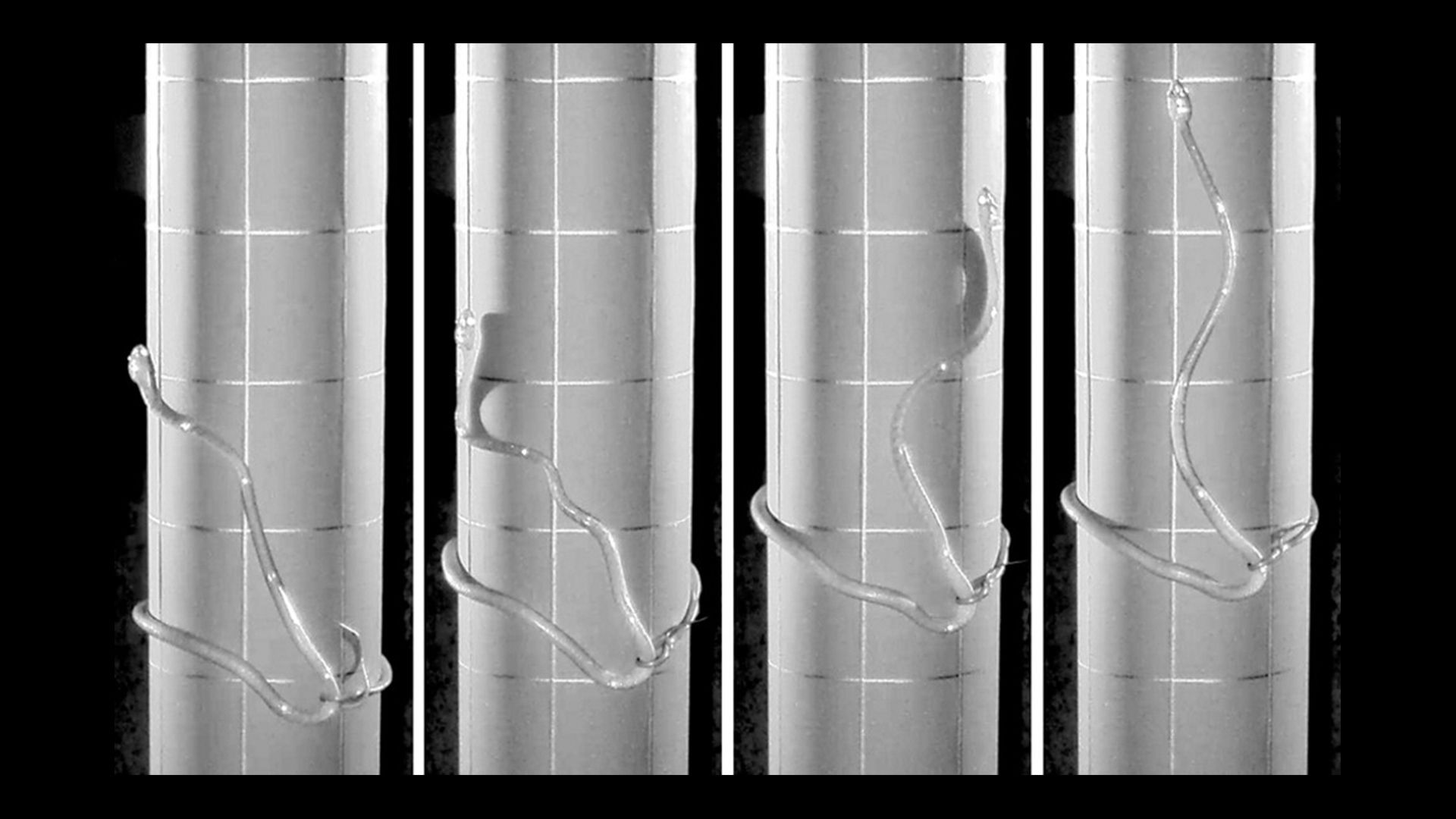

The bottom line: "Agreement and disagreement are biological. You can see it in the brain," says Hirsch. Go deeper: How we talk to each other about the tough stuff |     | | | | | | 5. Worthy of your time |  | | | Illustration: Brendan Lynch/Axios | | | | The science of mob thinking (Sara Fischer and me — Axios) Evolution's engineers (Kevin Laland and Lynn Chiu — Aeon) A Japanese forestry firm wants to put wooden satellites into orbit (The Economist) Scientists discover 10 billion-year-old "super-Earth" planet (Miriam Kramer — Axios) |     | | | | | | 6. Something wondrous |  | | | A brown tree snake lasso climbing. Credit: Savidge et al. Current Biology | | | | Scientists have discovered a new way snakes can move. Why it matters: The finding may aid bird restoration efforts by helping to develop more effective barriers to protect birds from their predators and it could inspire the design of robots to move through disaster areas, Kate Baggaley writes for Popular Science. Details: The brown tree snake (Boiga irregularis) is invasive in Guam where it ascends trees to feed on forest birds. - Researchers were testing whether large (5- to 8-inch-diameter) smooth poles could keep the snakes from climbing into nesting boxes when they observed a snake form a "lasso" with its body and pull itself up the pole.

- Snakes are known to have four modes of movement — rectilinear, lateral undulation, sidewinding and concertina.

- Typically they are seen climbing by gripping a pole near their head and tail and bending and extending their body like an accordion to climb in so-called concertina mode.

- "Lasso locomotion" is more of a struggle. "Slow speeds, slipping, frequent pausing and heavy breathing during pauses all suggest lasso locomotion is demanding," the researchers at Colorado State University and the University of Cincinnati report in Current Biology.

The big picture: By expanding its repertoire of moves, the species may be able to exploit new resources, contributing to "the success and impact of this highly invasive species," they write. |     | | | | | | A message from Babbel | | Start the new year with a new language | | |  | | | | In 2021, let language take you places with Babbel. The background: This language learning app gives you bite-sized, manageable lessons in a variety of languages. It'll have you speaking the basics in three weeks. Sign up today and get 60% off. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1300, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment