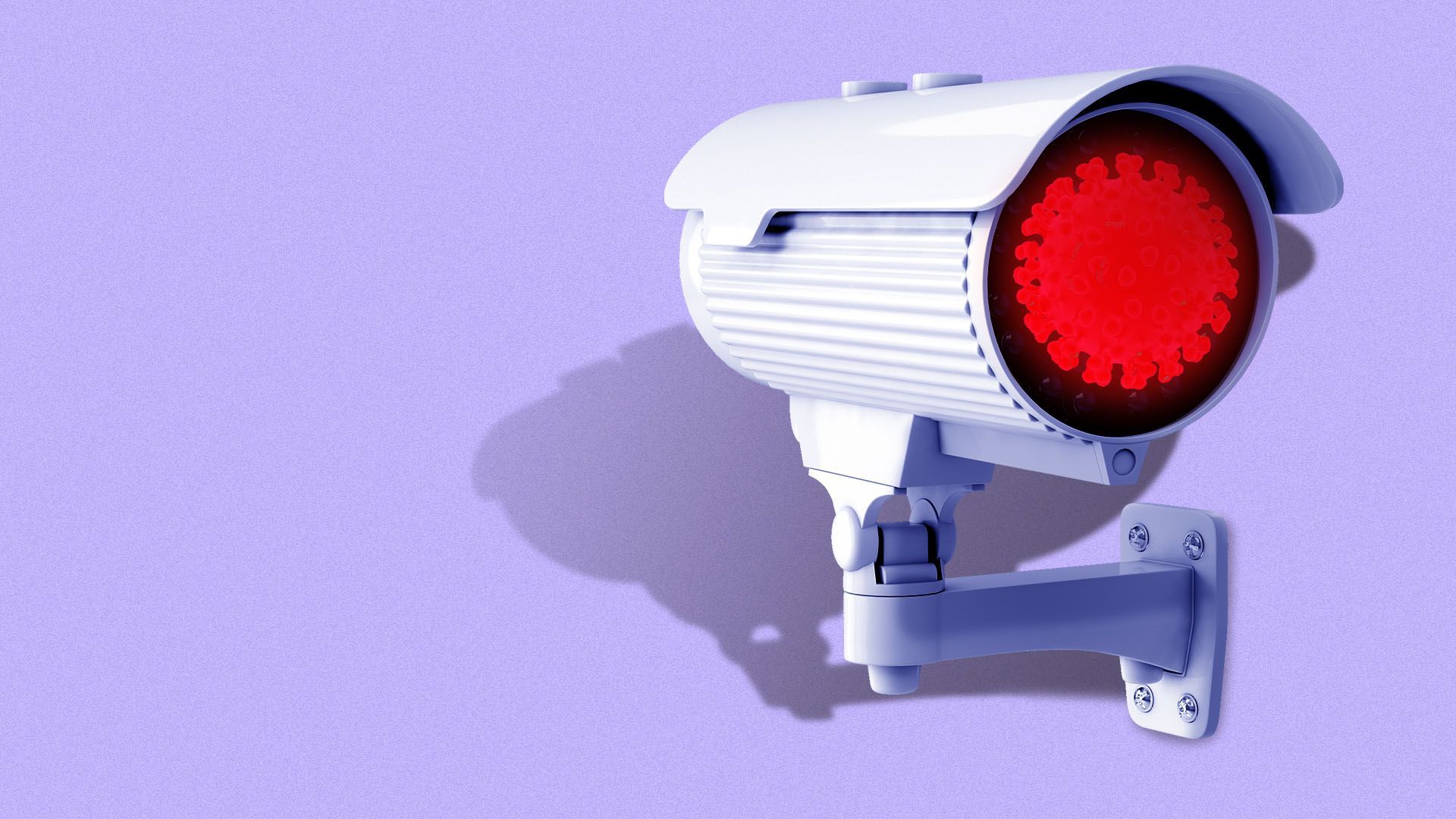

| | | | | | | Presented By Babbel | | | | Axios Future | | By Bryan Walsh ·Jan 13, 2021 | | Welcome to Axios Future, where the nation is reeling from a shocking change in leadership. If you haven't subscribed, do so here. Today's Smart Brevity count: 1,895 words or about 7 minutes. | | | | | | 1 big thing: Why COVID demands genetic surveillance |  | | | Illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios | | | | A seemingly more transmissible coronavirus variant is threatening the world — and exposing the U.S.' lackluster genetic surveillance. Why it matters: A beefed-up program to sequence the genomes of infectious disease pathogens infections could help the U.S. identify dangerous new coronavirus variants — and get the jump on pathogens that could ignite the pandemics of the future. Driving the news: New variants of SARS-CoV-2 — including the B.1.1.7 variant that appears to be helping to drive a tremendous spike in infections in the U.K. and Ireland — are being identified by scientists around the world, my Axios colleague Marisa Fernandez reports today. - While a few state health departments in the U.S. have identified a handful of B.1.1.7 cases, the CDC said on Friday that "neither researchers nor analysts at CDC have seen the emergence of a particular variant in the United States."

Yes, but: Genetic surveillance of coronavirus variants in the U.S. lags well behind dozens of other countries, which means we lack a clear picture of exactly how the novel coronavirus currently infecting more than 200,000 people a day is mutating here. - According to the nonprofit GISAID Initiative, the U.S. has only sequenced a little more than 60,000 cases since the start of the pandemic, or roughly 0.3% of all cases.

- That's a little more than half the cases sequenced by the U.K., the world's leader in genetic surveillance, and the median time it takes to post a sequence of the virus on GISAID in the U.S. is 85 days, slower than far poorer countries like Bangladesh and Sri Lanka.

Be smart: The bottleneck here isn't scientific. Genetic sequencing has gotten faster and cheaper, and every state in the U.S. has the technical capacity to decode viral genomes. - Rather, the U.S. lacks the kind of unified, national genetic surveillance program adopted by the U.K., which in the spring invested £20 million ($27 million) to launch a scientific consortium that standardized the sequencing and reporting of coronavirus variants.

- While the CDC in May brought together dozens of labs in an effort to accelerate sequencing, a report by the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine in July concluded current efforts are "typically passive, reactive, uncoordinated, and underfunded."

What they're saying: "You'll never find what you aren't actively looking for," as Michal Tal, a biologist at Stanford University, told the New Republic last month. - If the U.S. had a strong national genetic surveillance system in place, it could see evidence of more transmissible variants and amp up vaccination or lockdown procedures before outbreaks got even more out of control.

What's next: The incoming Biden administration may be open to the idea of a national genetic surveillance program, which would likely cost several hundred million dollars, according to the New York Times. - Another option is to accelerate efforts to sequence variant strains from wastewater samples in community sewage systems.

- A more systematic genetic surveillance program could also pay dividends beyond the COVID-19 pandemic, by helping scientists identify emerging pathogens as soon as possible.

What to watch: If the weak U.S. genetic surveillance system begins to pick up signs that a variant like B.1.1.7 is beginning to dominate cases here, it would indicate a very bad pandemic is about to get much worse. - And — since the coronavirus is constantly mutating — entirely new variants could show up, like those identified in Ohio today.

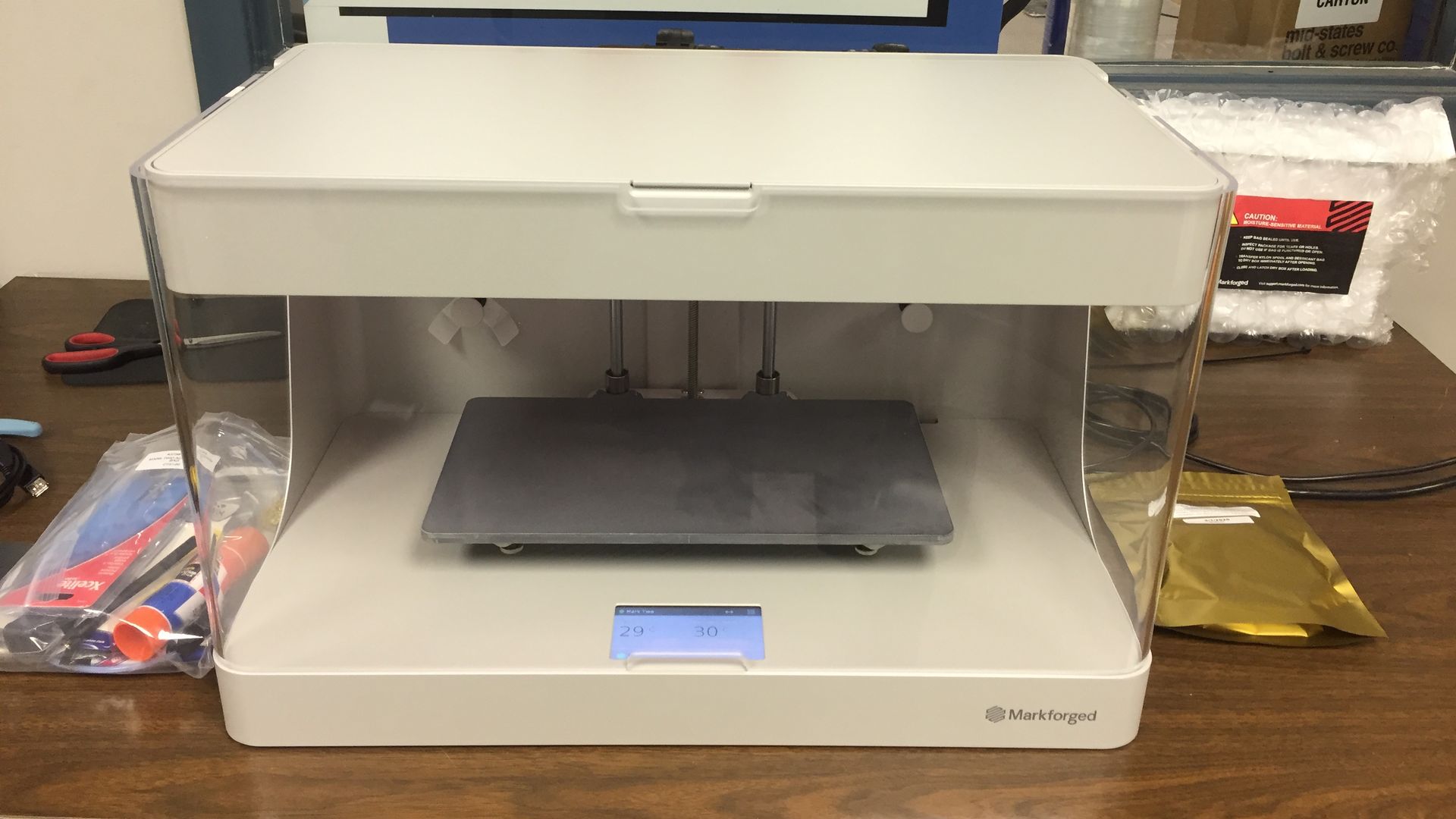

The bottom line: The pandemic has always been a race against time, and without a better genetic surveillance system, the U.S. will be perpetually slow out of the blocks. |     | | | | | | 2. An "emergency alert system" for PPE 3D printing |  | | | A 3D printer used for manufacturing personal protective equipment. Photo: International Engineering & Technologies, Inc. | | | | A 3D-printer platform is sending out machines to hundreds of manufacturers in Michigan as part of an effort to create a network that can print out personal protective equipment on demand. Why it matters: Networked 3D printers can serve as a rapidly scalable backup system for PPE — and showcase the potential of a new method of manufacturing. What's happening: In October, Automation Alley — Michigan's advanced manufacturing hub — launched Project DIAMOnD, an effort to create the world's largest 3D printer network. - The project aims to strengthen supply chains for PPE by distributing advanced 3D printers that could manufacture protective equipment like face shields on demand.

- This week, Markforged — creator of the world's largest metal and carbon fiber additive manufacturing platform — announced it sent 3D printers to more than 200 small and medium-sized manufacturers in the Wolverine State as part of the project.

How it works: "I liken it to a kind of emergency alert system" for manufacturing PPE on demand, says Michael Papish, chief evangelist at Markforged. - The advanced 3D printers operate on a network, so blueprints for PPE can be instantly sent out to manufacturers if the Michigan government feels a need to bolster supplies.

- When the printers aren't needed for PPE, manufacturers can use them as they desire to bolster their own businesses.

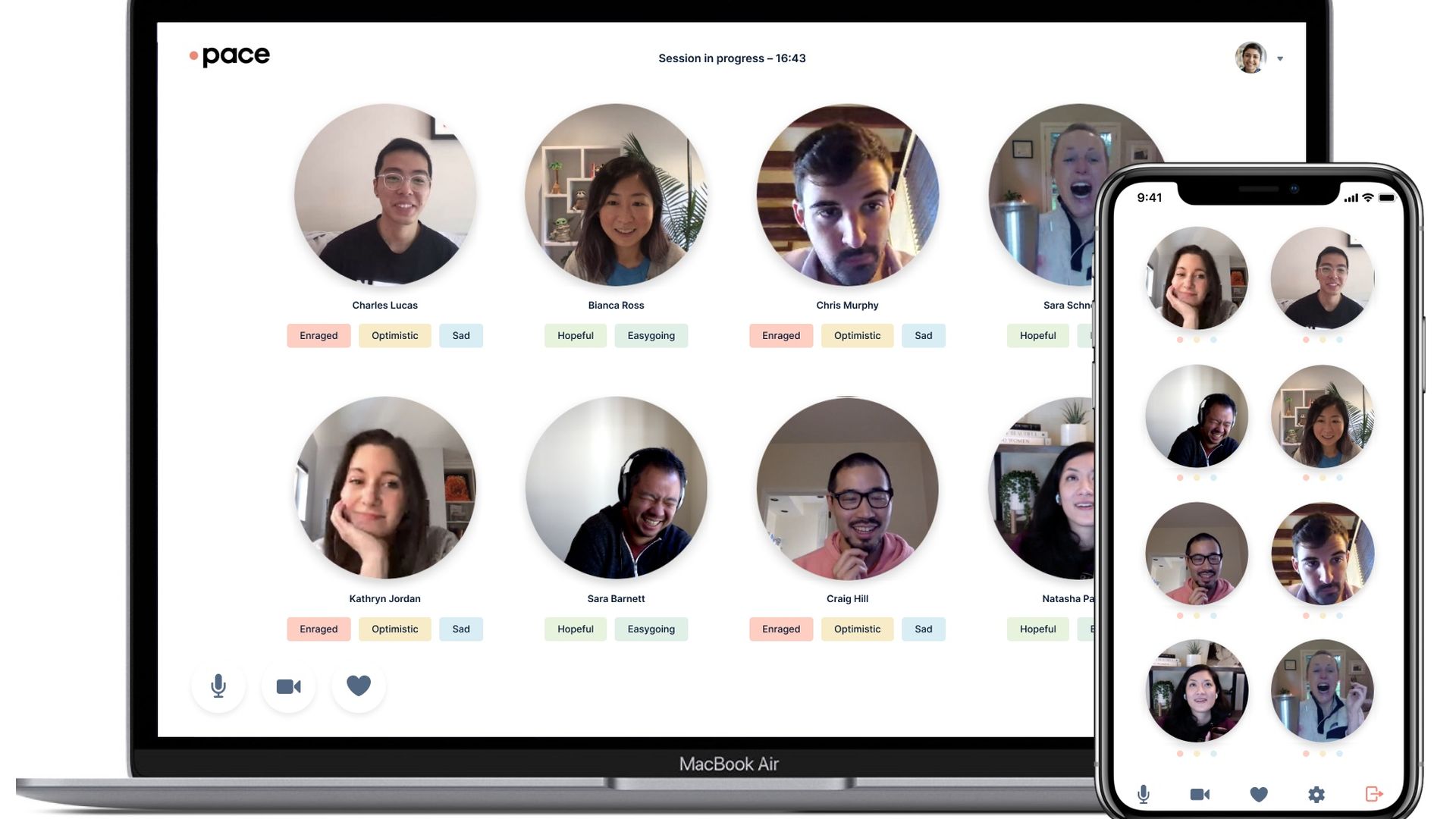

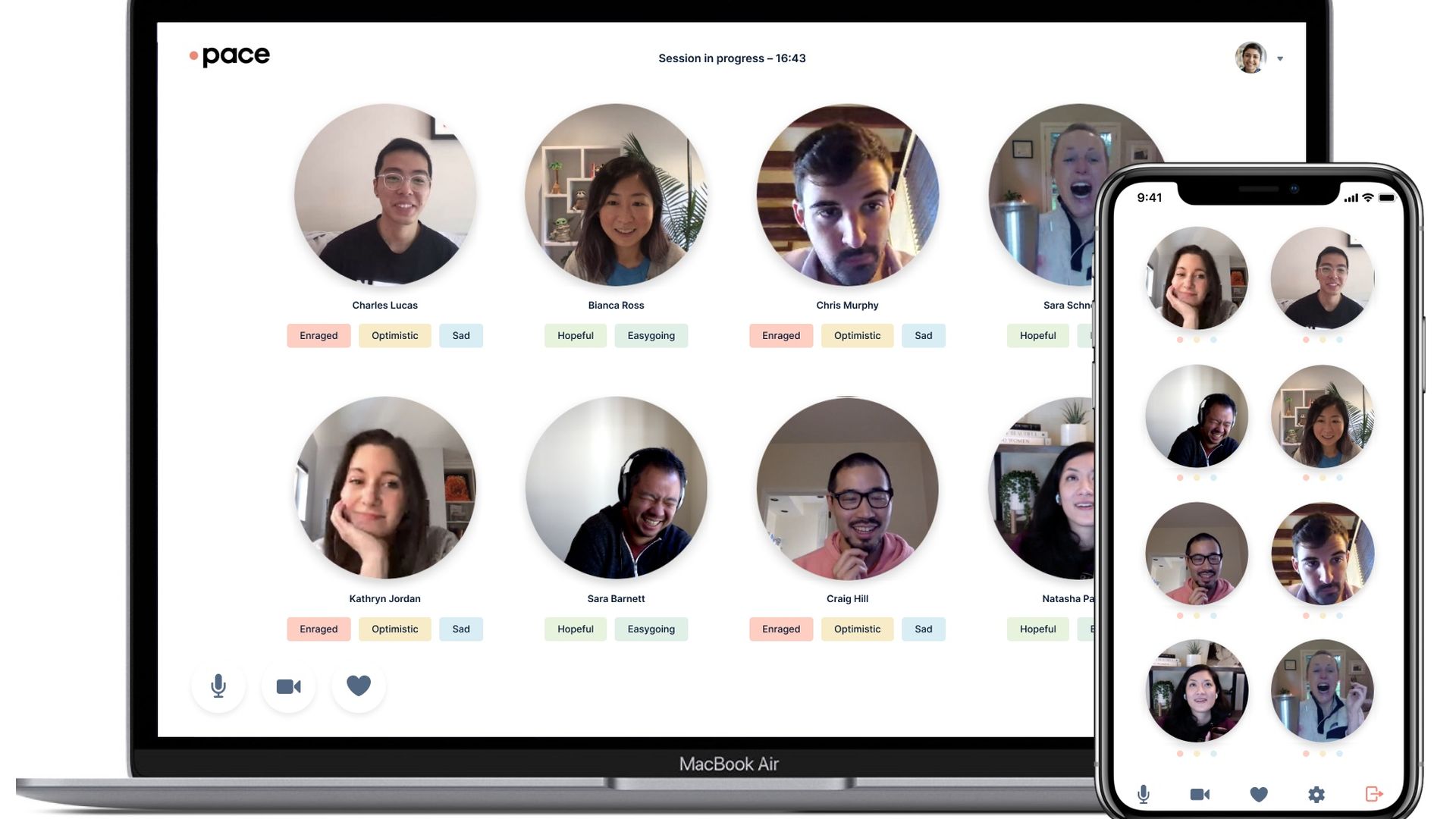

The big picture: The advantage of networked 3D printers is that a decentralized group of manufacturers can quickly be enlisted to produce equipment on the spot, without worrying about knotty supply chains. The bottom line: Just as software fixes can be rapidly iterated and pushed out to networked devices, connected 3D printers promises to bring the same flexibility "to making physical things," says Papish. |     | | | | | | 3. New mental health online service set to launch |  | | | Screenshot of Pace mental health app. Credit: Pace | | | | A team of Silicon Valley veterans is launching a new service that will address mental health issues through online group sessions. Why it matters: The pandemic has led to a worsening of mental health, as traditional in-person therapy has been largely curtailed. New services like Pace that aim to address mental health issues remotely could help close that gap. How it works: Pace will provide a form of group therapy that can be done over the web or on a smartphone, with users selecting communities that fit their own mental health needs. - Some of the first areas include relationship problems, career issues and parenting, as well as a separate section for founders struggling with stress.

- Groups are led by mental health facilitators and cost $45 per week, with users signing on for a season of therapy at a time.

Background: Jack Chou, Pace's CEO and co-founder, told Axios in the company's first interview that he helped come up with the idea for the startup while taking a break from an intense tech career that included stints as head of product at Affirm and Pinterest. - "It was really the first time in my life that I felt like I was struggling, trying to figure something out," says Chou. "And there was really nothing for people like me."

- Chou and his co-founders took inspiration from group fitness classes like SoulCycle, betting that "forms of group therapy could really be developed and brought to bear through technology to people wherever they were."

The big picture: Though the team began working on Pace before the pandemic hit and essentially closed most in-person mental health services, it is launching during a boom for teletherapy. - The online provider Talkspace agreed today to a $1.4 billion merger with the blank-check firm Hudson Executive Investment.

The bottom line: According to a Gallup poll from December, Americans' mental health is the worst it has been in two decades. - We need help, and we need it now.

|     | | | | | | A message from Babbel | | Start speaking a new language in three weeks | | |  | | | | In 2021, let language take you places with Babbel. The background: This language learning app gives you bite-sized, manageable lessons in a variety of languages. It'll have you speaking the basics in three weeks. Sign up today and get 60% off. | | | | | | 4. The flu season that isn't |  Data: CDC; Chart: Sara Wise/Axios Thanks largely to social distancing and mask-wearing — as well as higher uptake of the flu vaccine — influenza deaths this season are almost nonexistent. Why it matters: The drastic drop in infections of influenza and other circulating respiratory viruses has given the U.S. health care system a welcome respite at a time when COVID-19 is rampaging. By the numbers: According to the CDC, the U.S. recorded just five flu deaths in the 52nd week of 2020, a period that usually represents the height of the influenza season. - That is 40-fold fewer deaths than the same week in 2019, and more than 130-fold fewer deaths than during the bad flu season of 2017.

- According to data from BioFire Diagnostics, levels of nearly every common respiratory and gastrointestinal virus are currently all but undetectable.

How it works: It turns out if you drastically reduce global travel, close public workplaces and schools, and promote mask-wearing and handwashing, you'll cut off opportunities for common pathogens to spread. - It also helps that a record number of flu vaccine doses have been shipped this season, and an estimated 53–54% of American adults had gotten a shot by the end of December, significantly higher than the same time last year.

The big picture: Historically low levels of flu and other common viruses are happening at the same time the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S. is at its worst. - That's not surprising: While common viruses have circulated for years and there is a base level of resistance in the population, no one had encountered SARS-CoV-2 before it emerged in China a year ago, and the virus continues to spread rapidly through the vulnerable population.

What to watch: With each week that passes with unusually low levels of flu, susceptibility to the virus will rise, potentially setting up the U.S. for a harsh rebound in the future. - That may be what's happening in Australia, where flu cases during its winter season were virtually nonexistent, only to bounce back this December, when the flu is usually absent in the Southern Hemisphere.

The bottom line: While it's good to see fewer deaths from influenza, SARS-CoV-2 is ravaging the U.S. at an entirely different magnitude, with more Americans dying of COVID-19 last week than the entire number of flu deaths last season. |     | | | | | | 5. Worthy of your time | | What happened to social mobility in America? (Branko Milanovic — Foreign Affairs) - The U.S. is in the grip of a new aristocracy that dominates both wages and capital — a development unprecedented in the country's history.

mRNA technology gave us the first COVID-19 vaccines. It could also upend the drug industry (Walter Isaacson — TIME) - The biographer of Steve Jobs on how the technology used to make COVID-19 vaccines could revolutionize medicine.

Are experts real? (Alvaro de Menard) - A fascinating blog post that explores how increasing specialization in the sciences had led to a crisis of confidence in expertise.

Lost passwords lock millionaires out of their bitcoin fortunes (Nathaniel Popper — New York Times) - I have no idea how much bitcoin is truly worth, but the schadenfreude value of this article — about people who can't access bitcoin trading for hundreds of millions of dollars because they forgot their passwords — is incalculable.

|     | | | | | | 6. 1 education thing: The decline and fall of history |  | | | According to a 2016 study, 71% of Americans think this guy was president. (Reality check: He was not.) Photo: omersukrugoksu | | | | History has plummeted over the past decade as a field of study for U.S. college students. Why it matters: The U.S. is undergoing unprecedented political crises, but the decline of historical study means that many of us may lack perspective on just what is happening to our country. By the numbers: Since the economic crisis in 2008, history has seen the steepest decline of all major disciplines in the number of bachelor's degrees awarded. - In 2008, the National Center for Education Statistics reported 34,652 majors in history, but by 2017 — the most recent year that data was available — that number had fallen to 24,266, as historian Benjamin M. Schmidt noted in 2018.

- The raw number of history BAs awarded in 2017 was smaller than in any year since 1991, even as overall college enrollment has grown.

- The percentage of college-age adults with history degrees is less than half of its peak in 1971.

Context: History's decline has been especially steep since 2011–12, "the first years for which students who saw the financial crisis in action could easily change their majors," as Schmidt wrote. The bottom line: The epistemic crisis the U.S. is clearly experiencing has numerous causes, from the rise of unfiltered social media to seemingly deliberate efforts by some in the media to mislead the public. - But actual knowledge of U.S. history is one of the best prophylactics against conspiracy think — and it's one we abandon at our peril.

|     | | | | | | A message from Babbel | | Start the new year with a new language | | |  | | | | In 2021, let language take you places with Babbel. The background: This language learning app gives you bite-sized, manageable lessons in a variety of languages. It'll have you speaking the basics in three weeks. Sign up today and get 60% off. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1300, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment