| | | | | | | Presented By Northrop Grumman | | | | Axios Space | | By Miriam Kramer ·Nov 03, 2020 | | Thanks for reading Axios Space. At 1,182 words, this week's newsletter will take you about 4½ minutes to read. 🇺🇸 Happy Election Day! Here are the best ways to follow along with our coverage today and throughout the week: Please send your tips, questions and Election Day jitters to miriam.kramer@axios.com, or if you received this as an email, just hit reply. | | | | | | 1 big thing: The end of the ISS will mix up space geopolitics |  | | | Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios | | | | Twenty years after astronauts moved in full time, the International Space Station is nearing its end, opening up a new geopolitical landscape above Earth. Why it matters: The end of the program will force nations collaborating on the station, along with China and others new to the human spaceflight scene, to recalibrate. - They could also turn their attention to cooperating — or competing — on the Moon instead.

State of play: The U.S. could end its support of the space station at the end of 2024, but NASA and its partners are considering extending its life until 2028. - Either way, countries involved in the ISS program are already pivoting to collaborate on NASA's Artemis Moon mission, which is expected to bring people to the lunar surface by 2024.

- The European Space Agency signed on last week to help build the small Gateway space station that will orbit the Moon and act as a jumping-off point for missions to the surface.

- Japan and Canada, nations that also collaborate on the ISS, are working on Gateway as well.

The intrigue: The space station has been a constant in orbit, tying the U.S., Russia and about a dozen other countries together in their space ambitions. - But the end of the ISS could pull the U.S. and Russia away from one another.

- It's not yet clear where Russia — one of the largest supporters of the ISS — will land when it comes to post-space station cooperation.

- Dmitry Rogozin, the head of Russia's space agency Roscosmos, has already spoken out against the Gateway station, calling the Artemis Moon plans too "U.S. centric."

Between the lines: Another wrinkle in the post-ISS geopolitical landscape is China's ambition to build its own station orbiting Earth, which is expected to come online around the time the ISS ends. - That could pull possible U.S. partners in space to China instead, with some experts suggesting Russia might find new ways to collaborate with China.

- "I don't think Russia and China are immediately going to become best buddies. ... They've got their own complications in their relationship, but it does provide an alternative and a different option for countries that might not have been able to get on board with the U.S., Russia and the current ISS," Victoria Samson of the Secure World Foundation told me.

The big picture: Not all attention will turn to the Moon at the end of the space station, however. NASA is hoping to make use of private space stations under development as a proving ground for missions to deeper space. - Those space stations could be places where nations are able to collaborate with one another as well.

- "My guess would be the international partners would be buying time on those commercial vehicles," former NASA administrator Charles Bolden told me.

- Yes, but: In order to smoothly transition between the ISS and these private stations, companies would need to have them operational in orbit before the end of the space station, an aggressive timeline that may not be met.

The bottom line: Geopolitics are shifting in space as the ISS winds down and nations start to look to the Moon as a place for collaboration. |     | | | | | | 2. A brief history of voting from space |  | | | NASA astronaut Kate Rubins and her orbiting voting booth. Photo: NASA | | | | One vote in the 2020 U.S. presidential election wasn't cast from a voting booth or by mail, but from 250 miles up aboard the ISS. The big picture: NASA astronaut Kate Rubins is far from the first person to exercise her civic duty from orbit. Cosmonauts and astronauts have voted from space for decades. - "I think it's really important for everybody to vote, and if we can do it from space, then I believe folks can do it from the ground, too," Rubins told AP last month.

How it works: Astronauts in space can vote by receiving an encrypted ballot from mission control. They then fill out the ballot and send it back to Earth, where it's sent to a registrar who converts the electronic ballot and counts the vote. - That process is possible because Texas passed a law making it legal for residents of the state to vote from orbit.

- No other states have this law on the books, but all active NASA astronauts need to live near Houston, so the Texas law is effectively a catch-all for Americans heading to space right now.

Background: The first people to vote from space were Russian cosmonauts aboard the space station Mir, according to space historian Robert Pearlman. - "Yury Usachov and Yuri Onufrienko were aboard Mir with American astronaut Shannon Lucid. In June of 1996, the two of them voted in the Russian presidential election that year," said Pearlman, who runs the website Collectspace.com.

- NASA astronaut David Wolf voted in a local election from Mir in 1997.

- And NASA's Leroy Chiao became the first American to cast a vote for president from orbit aboard the ISS in 2004.

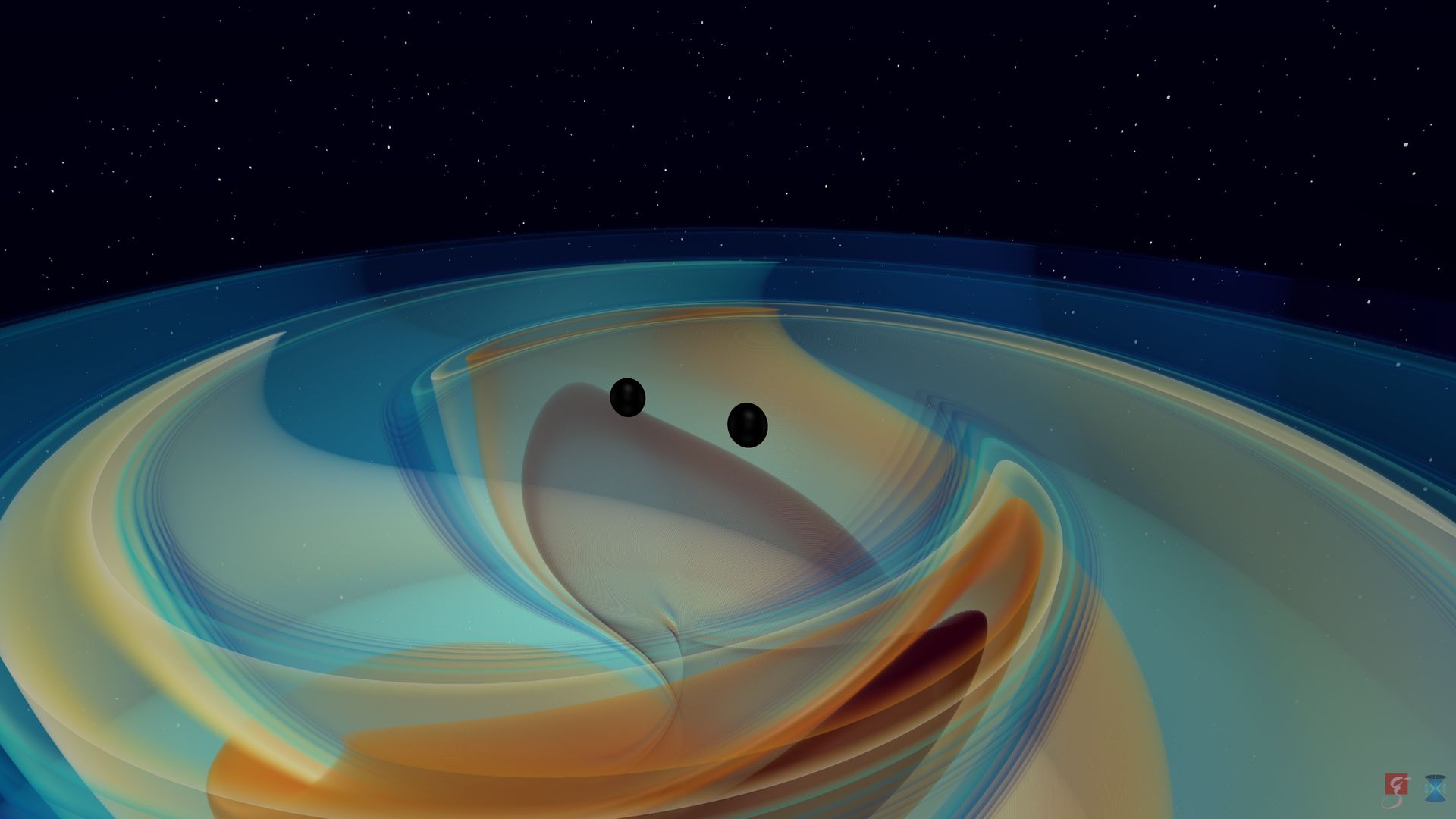

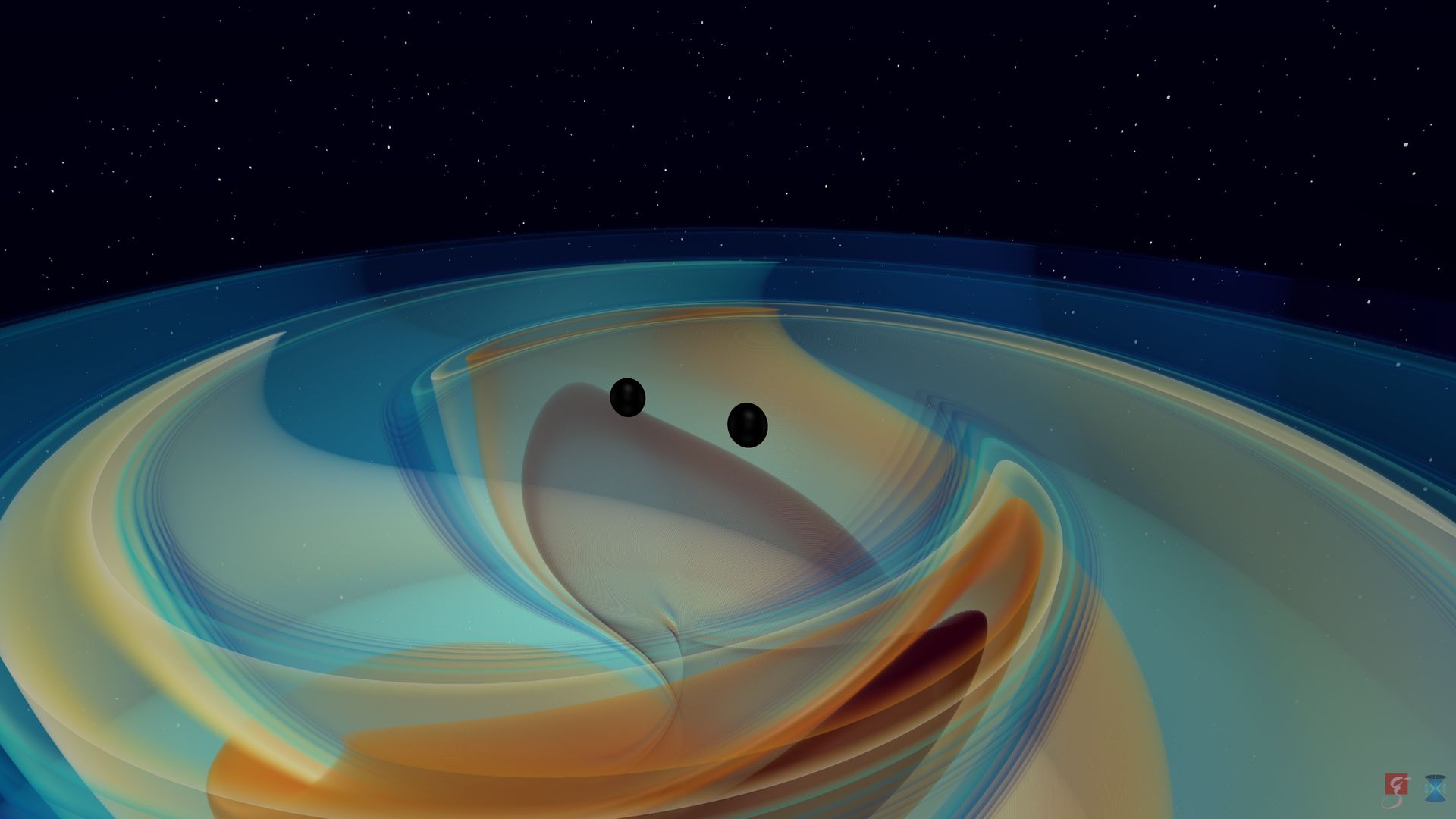

What's next: Eventually, space voting laws might have to be adopted elsewhere in the U.S., if private astronauts are going to be living and working in space for the long haul. |     | | | | | | 3. Glut of gravitational waves |  | | | A simulation of two black holes merging. Image: N. Fischer/H. Pfeiffer/A. Buonanno/SXS | | | | Scientists have found 50 signals from gravitational waves sent out by massive objects slamming into each other in space. Why it matters: The more scientists find these signals from cosmic crashes, the more they are able to piece together a fuller understanding of the universe, including the formation of black holes. What they did: Researchers found 39 signals from gravitational waves sent out by colliding black holes and neutron stars picked up by the LIGO and Virgo detectors between April 1 and Oct 1, 2019. - "The sharp increase in the number of detections was made possible by significant improvements to the instruments with respect to previous observation periods," according to the LIGO statement.

How it works: The two L-shaped LIGO detectors pick up gravitational waves by using a laser that runs down the length of each arm of the L. - That laser bounces back to the bend in the L when it hits a mirror placed at each end.

- If both lasers get back to the middle at the same time, that means no gravitational wave has passed through, but if they're out of alignment, it could indicate a gravitational wave passed by, stretching the fabric of space and time as it did.

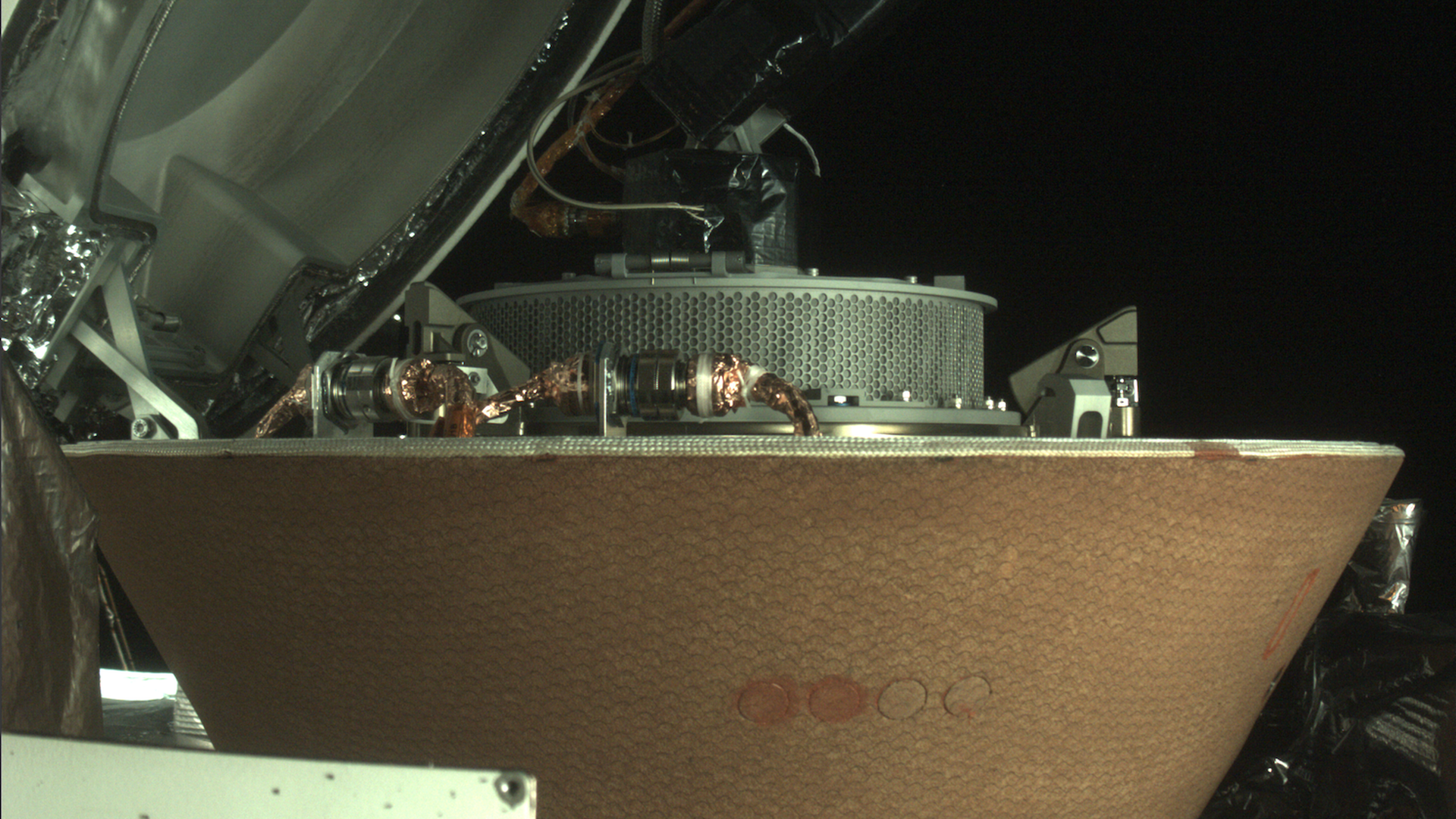

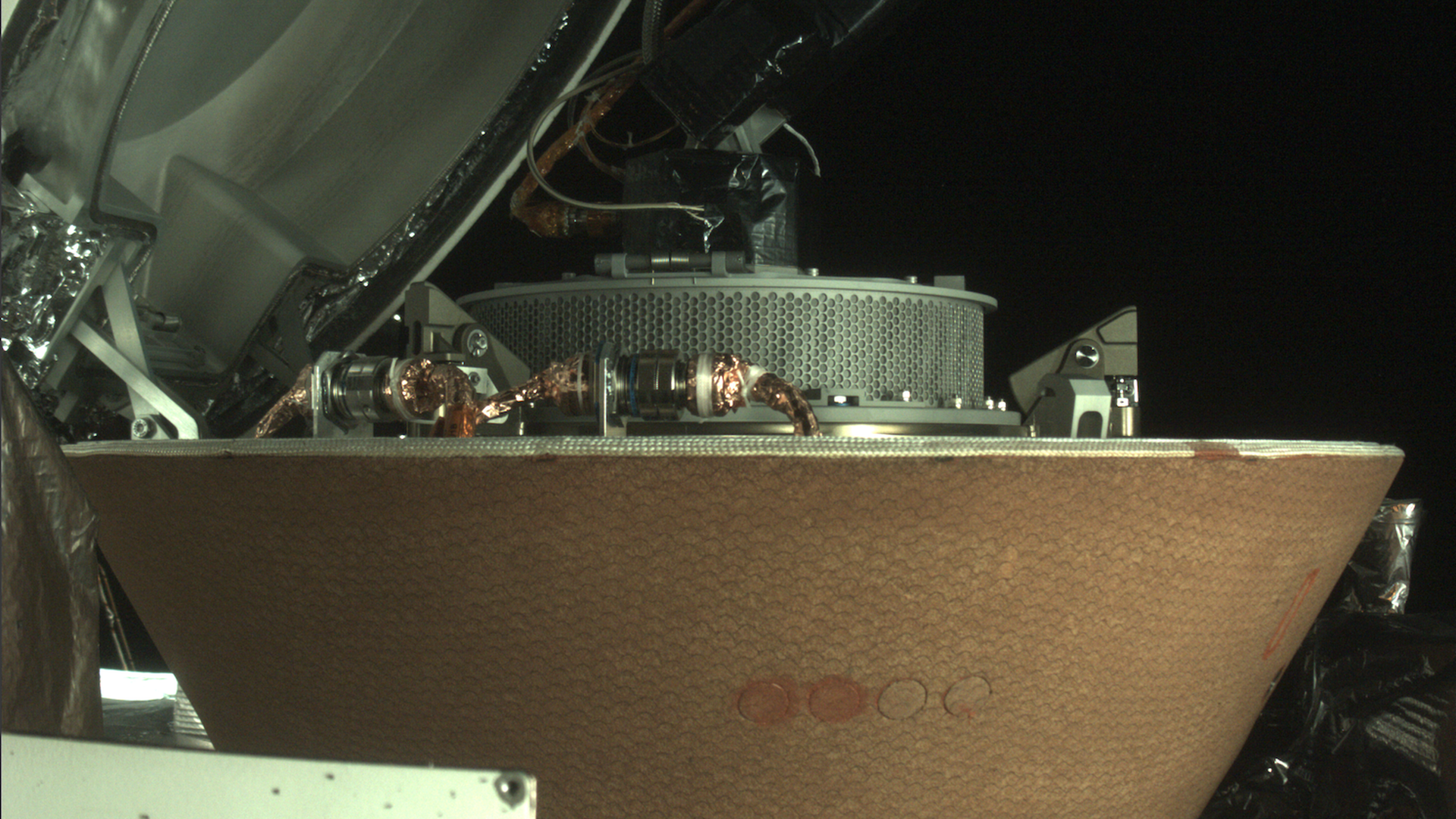

|     | | | | | | A message from Northrop Grumman | | It's impossible to connect the joint force as one. Until it's not | | |  | | | | How is Northrop Grumman Cyber defining possible? Here's how: We provide powerful, scalable networks and integrated capabilities that ensure warfighters and the systems they depend on can act as one joint force across every domain, service and mission. Learn more about how. | | | | | | 4. Out of this world reading list |  | | | Photo: NASA/Goddard/University of Arizona/Lockheed Martin | | | | U.S. military keeps sharp eyes on orbit as congestion grows (Sandra Erwin, SpaceNews) The rogue planets that wander the galaxy alone (Marina Koren, The Atlantic) SpaceX replacing two Falcon 9 engines ahead of crewed flight (Loren Grush, The Verge) NASA spacecraft stows sample of asteroid to bring back to Earth (Axios) |     | | | | | | 5. Your weekly dose of awe: Spooky season in space |  | | | Photo: NASA/ESA/W. Keel | | | | The ghostly evidence of a collision between two galaxies floats 120 million light-years away. - The two misshapen galaxies look like a set of spooky eyes with a crooked smile beneath them, in this photo from the Hubble Space Telescope.

- "The arm embraces both galaxies," NASA said in a statement, referencing the "smile." "It most likely formed when interstellar gas was compressed as the two galaxies began to merge. The higher density [of material] precipitates new star formation."

What's next: According to NASA, eventually this merging galaxy pair may become a huge spiral galaxy, far larger than our Milky Way. |     | | | | | | A message from Northrop Grumman | | It's impossible to connect the joint force as one. Until it's not | | |  | | | | How is Northrop Grumman Cyber defining possible? Here's how: We provide powerful, scalable networks and integrated capabilities that ensure warfighters and the systems they depend on can act as one joint force across every domain, service and mission. Learn more about how. | | | | Big thanks to Alison Snyder, Sheryl Miller and David Nather for editing this week's edition. If this email was forwarded to you, subscribe here. 👩🚀 | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1300, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment