| | | | | | | Axios Future | | By Bryan Walsh ·Dec 23, 2020 | | Welcome to Axios Future, where we have only one thought looking back on 2020: what a decade this year has been. - Thank you so much for following the new Axios Future through a very eventful 10 months and 77 newsletters.

- If you haven't subscribed, do so here, and send feedback and tips to bryan.walsh@axios.com.

- My New Year's resolutions include faster email responses.

Today's Smart Brevity count: 1,923 words or about 7 minutes. | | | | | | 1 big thing: 2020 was bad — but not nearly the worst |  | | | Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios | | | | 2020 will go down in infamy for all the obvious reasons, but history shows it doesn't actually rank among humanity's worst years. Why it matters: Understanding just how far we've come from the years when life was nasty, brutal and short can help us put the pain of 2020 in perspective, and appreciate the progress we need to defend. What's happening: You could take your pick of statistics that underscore just how terrible 2020 was. Here's an obvious one: the U.S. is on track to record more than 3.2 million deaths this year, the highest in the country's history. - That represents more than 400,000 additional deaths from the previous year, for an annual increase of about 15%.

The big picture: It's numbers like these that prompted my former colleagues at TIME magazine to give 2020 the Adolf Hitler treatment. Yes, but: As even the TIME piece acknowledges, the U.S. has had worse years. - In 1918 the U.S. lost tens of thousands of people in the trenches of World War I and hundreds of thousands more in the Spanish flu pandemic.

- Deaths that year rose an astounding 46% from 1917, and life expectancy dropped by nearly 12 years, compared to a likely three-year decline in 2020.

Background: Go back further and widen your lens, and far more terrible years begin to crop up. - Take 1816, known as the "Year Without a Summer," thanks to a massive volcanic eruption in 1815 that spread sun-blocking ash throughout the atmosphere. Average global temperatures fell and crops failed, leading to terrible famine.

- Or 1349, perhaps the worst year of the Black Death pandemic, which would eventually kill a third or more of Europe's population alone, equivalent to at least 247 million deaths today.

- And don't forget 536, which the journal Science memorably called "the worst year to be alive." A volcanic eruption in Iceland early that year cast Europe and parts of the Middle East and Asia into a literal dark age, intensifying famines and hastening the spread of bubonic plague.

Be smart: What these anni horribili have in common is that they concentrated the two conditions that have been the default state until recently: disease and starvation. - For all but a tiny elite, humanity until the 20th century was caught in a Malthusian trap, with any opportunity for significant population growth or material improvement constrained by limited agricultural productivity.

- The world only began to escape that zero-sum game with the advent of industrialization in the 19th century, which in turn was only possible because the sanitary revolution and the later development of vaccines and antibiotics enabled us to largely conquer infection, allowing cities and trade to flourish.

By the numbers: The global economy is projected to contract by more than 4% this year, and as many as 115 million people could fall back into extreme poverty. - But that would still leave an economy more than twice as large as it was just 30 years ago, when more than a third of the world's population was in extreme poverty.

- Today, even with COVID-19, that figure is closer to 9%.

The catch: As 2020 has painfully demonstrated, just because life has been getting better all the time doesn't mean it will continue to do so. - Industrialization enabled us to escape the Malthusian trap, but it also put us on the path to catastrophic climate change — likely the biggest headwind we'll face in the decades ahead.

- More to the point, we don't judge our standard of living against the deep and terrible past, but from our recent memories and what we see around us, so we have every right to feel terrible about 2020.

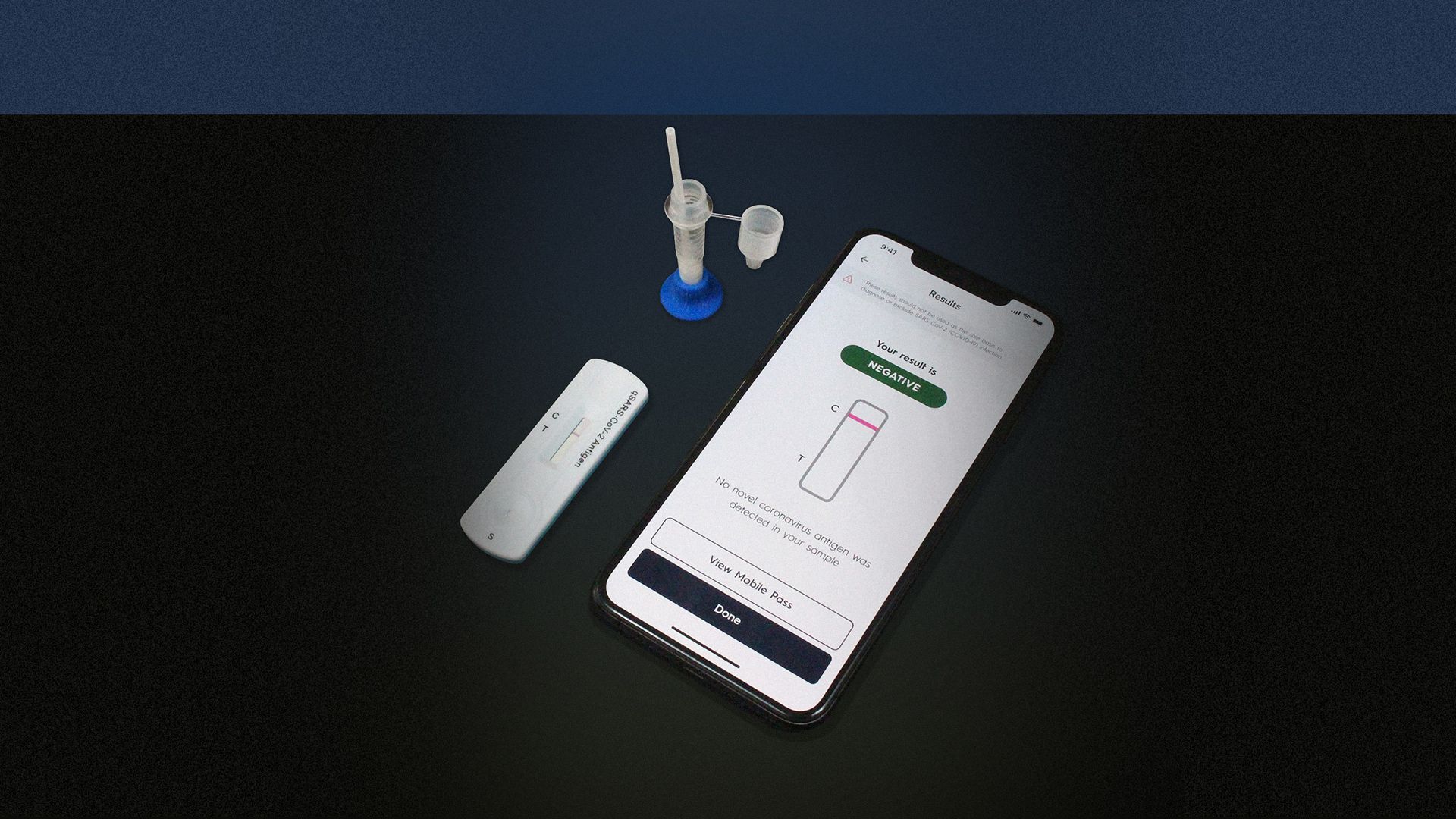

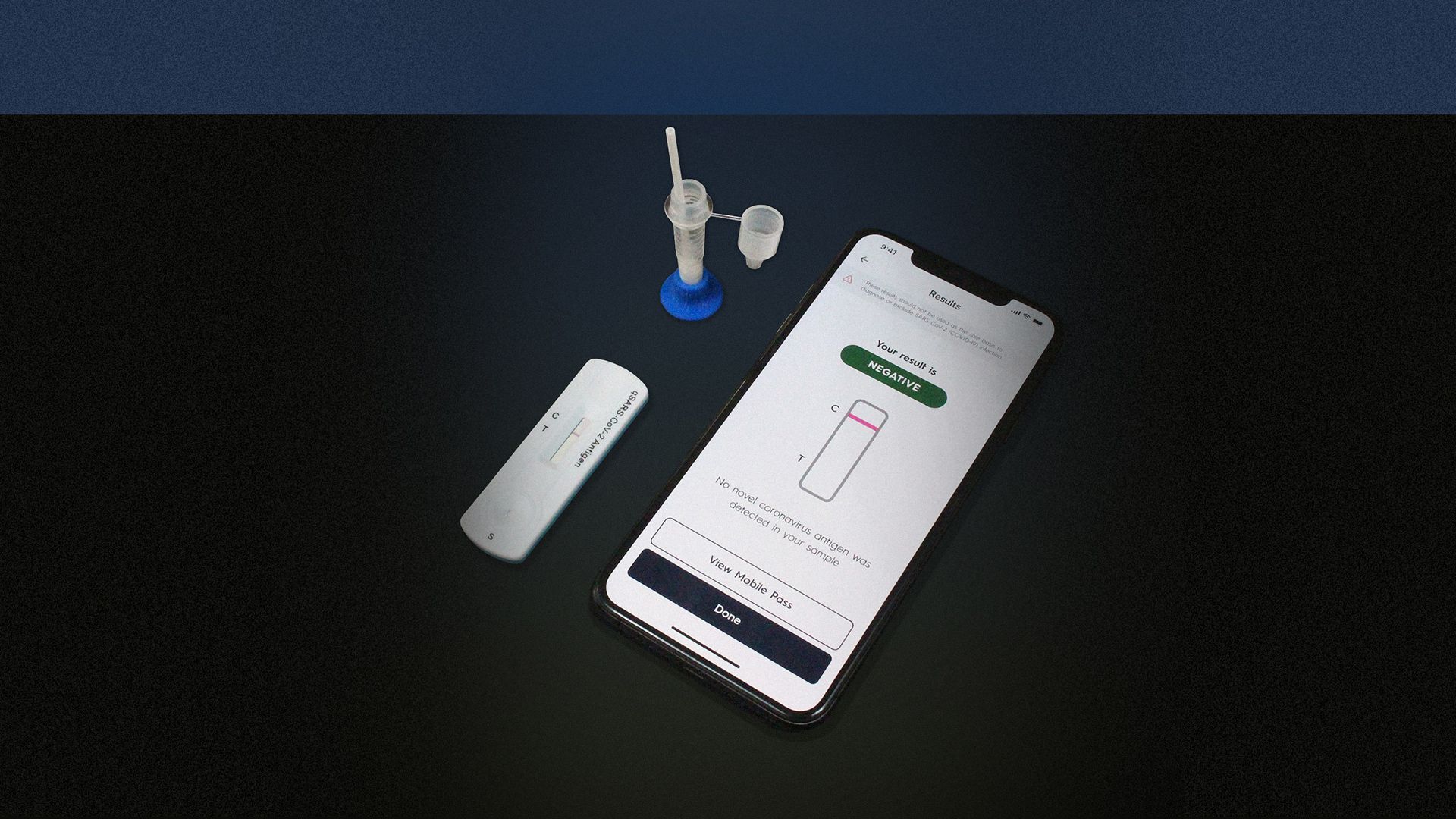

The bottom line: 2020 could have been worse, and historically at least, we've seen much, much worse. That might be the best glimmer of hope in an otherwise pitch-black holiday season. |     | | | | | | 2. A new deal to deliver at-home rapid COVID tests |  | | | The Gauss/Cellex rapid at-home COVID-19 test. Credit: Gauss | | | | The company behind one of the new fully at-home COVID-19 tests is partnering with a digital health platform to deliver rapid diagnostics to consumers. Why it matters: The new partnership can help mass, at-home testing efforts to scale up rapidly at a moment when the pandemic is spinning out of control and population-wide vaccination is still months away. Driving the news: Gauss, a computer vision startup, is partnering with the digital health platform Truepill to speed the same-day delivery of millions of rapid at-home COVID-19 tests that can be ordered online. - The antigen tests, developed with the biotech startup Cellex, can be taken and read at home using a smartphone, delivering results within 15 minutes.

- The test is still awaiting emergency use authorization from the FDA — though Gauss expects approval to come through within days — and will be priced in the $30 range.

- Gauss is working to produce a million tests over the next month, with plans to scale up to 30 million tests in the first quarter of 2021.

Context: Michael Mina, of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and Kristian Andersen, of the Scripps Research Institute, laid out the case for mass, self-administered rapid at-home tests in an article published in Science on Monday. - Mina and Andersen want governments to provide the tests free of charge. The price tag would reach the billions — but the pandemic may cost the U.S. alone more than $16 trillion, so that seems like a good deal.

|     | | | | | | 3. Introducing an AI that can plan |  | | | DeepMind's MuZero can master games without being told the rules. Credit: DeepMind | | | | An AI company has published research today detailing a machine-learning agent that can figure out how to play and win multiple games with no prior instruction. Why it matters: The new research shows that an AI can learn by observation, much as humans do, which will have real-world ramifications that go well beyond the chessboard. Driving the news: In a paper published in the journal Nature, researchers at Google-owned DeepMind described the science behind MuZero, an AI agent that has shown the ability to "plan winning strategies in unknown environments," as the company described in a post. - MuZero mastered Go, chess, shogi and Atari games, performing as well as the company's earlier agent AlphaZero on the board games and beating all previous algorithms on video games like Pac-Man.

Background: DeepMind's earlier AlphaZero system relied on look-ahead search to rapidly select the best possible moves at a given time. But it only works if it has pre-programmed knowledge of how the game operates. - Other algorithms try to learn an accurate model of a game's environment, which they can then use to plan strategy. But visually rich games like Pac-Man — let alone anything an AI might encounter beyond the console — are difficult for even highly capable algorithms to model.

How it works: MuZero combines these two approaches by learning a model that relies only on the most important aspects of an environment, which it can then exploit with look-ahead search. - As MuZero tries one action after another, it learns the rules of the game while noticing the rewards and penalties, refining its methods until it hits on a winning strategy.

- It's not unlike how a child — albeit one with infinite patience and Google's near-infinite computing budget — would learn to play a game.

What's next: MuZero's nimble efficiency means that it should have more success with real-world applications, and DeepMind says it's already using it to invent better video compression. - Other potential applications include protein design and automated vehicles.

The bottom line: Human beings' cognitive super power is our ability to generalize from what we learn and use that to plan ahead. If AIs can fully master that skill, the possibilities could be endless. |     | | | | | | 4. Human rights abuses from above |  | | | Photo: NASA | | | | Suspicious behavior on ships that may be subjecting their crews to forced labor can be seen from space, my Axios colleague Miriam Kramer writes. Why it matters: Forced labor is a known issue in the international fishing industry, but the scale and scope of it are difficult to quantify. The study could be the catalyst for developing tools to better enforce laws to end these human rights abuses. What they found: The authors of the new study, published Monday in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, used machine learning and satellite data collected between 2012 and 2018 to analyze about 16,000 long-liner, squid jigger and trawler vessels, including 22 ships with known human rights abuses. - The team, which included human rights experts, found 27 high-risk behaviors that could indicate forced labor and can be seen using satellite data compiled by Global Fishing Watch.

Yes, but: The researchers behind the study emphasized this new work is a proof of concept that isn't ready to be used as a predictive tool to stop forced labor in real time. - "We are not accusing any specific vessels here of forced labor," co-author of the study David Kroodsma of Global Fishing Watch told Axios. "We are simply showing that there's a high risk of it across the fleet, based on their behavior. And the next step is to get more information."

|     | | | | | | 5. Worthy of your time | | Amazon has turned a middle-class warehouse career into a McJob (Matt Day and Spencer Soper — Bloomberg) - The e-commerce giant has hired hundreds of thousands of people for its warehouses during the pandemic, but an investigation finds that many workers can barely make ends meet.

The creator economy needs a middle class (Li Jin — Harvard Business Review) - Social media and streaming has made multimillionaires out of a few winners, but it won't be sustainable without policies that support a living income for far more creators.

The secret to success? Having a big sister (Nurith Aizenman — NPR) - Research from Kenya suggests that children with older sisters — who perform significant caretaking for siblings — do better in life. (Apologies to my younger brother Sean, who has managed to do pretty well despite me being a guy.)

How to give a meaningful holiday gift this year (Sigal Samuel — Future Perfect) - An effective altruism guide to holiday gifting this year, just in time for us procrastinators.

|     | | | | | | 6. 1 accountability thing: What I got wrong in 2020 |  | | | Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios | | | | No futurist — except maybe MuZero one day — gets every prediction right. Why it matters: Pundit accountability is a valuable if slightly embarrassing habit for journalists to adopt. If we can figure out where we went wrong in the past, maybe we'll be able to improve our batting average in the future. For the record: What follows is a partial list of some of Future's more notable mis-hits. The coronavirus is a force for deglobalization: On May 20, I wrote that "the COVID-19 pandemic is rolling back the tide of globalization, both economically and politically." - Reality check: While the earliest stages of the pandemic — when the Chinese economy was totally locked down — seemed to signal the coming unwinding of international supply chains, global trade is bouncing back and China's export-driven economy is going strong.

- Yes, but: Automation and 3D printing might eventually make it cheaper to reshore, but not in the near future.

The argument for a billion Americans: On Sept. 12, I wrote that "if the U.S. wants to counterbalance a rising China, it needs to compete on sheer numbers." - Reality check: In all fairness — to me at least — I was describing the case laid out by journalist Matthew Ygelsias in his recent book. But there's no sign the U.S. is ready to adopt any of the family- and immigration-supporting policies major population growth would require, and my Axios colleague Felix Salmon had a pretty good counterargument to the whole concept.

- Yes, but: I still think it's a good idea on both merits and justice, but we're in the reality-describing business here, and this isn't happening.

"Cyberpunk 2077" goes back to the future: On Dec. 12, I wrote that the video game "could well be the future of leisure." The bottom line: As the physicist Niels Bohr supposedly said, "Prediction is very difficult, especially if it's about the future." - Here's to a slightly more accurate 2021.

|     | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1300, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment