| | | | | | | Presented By Capital One | | | | Axios AM Deep Dive: | | Hard Truths | | By Mike Allen ·Nov 14, 2020 | | View in browser | | Good afternoon and welcome to the second edition of our Hard Truths Deep Dive series. - As the fall semester of an unprecedented school year winds to a close, our focus is on race and education, led by Erica Pandey, Marisa Fernandez and Michele Salcedo.

Join Axios on Tuesday at 12:30 p.m. ET for our second Hard Truths event, a discussion on education. Register here. - 🎧 Hear a special edition of the "Axios Today" podcast examining police presence in schools.

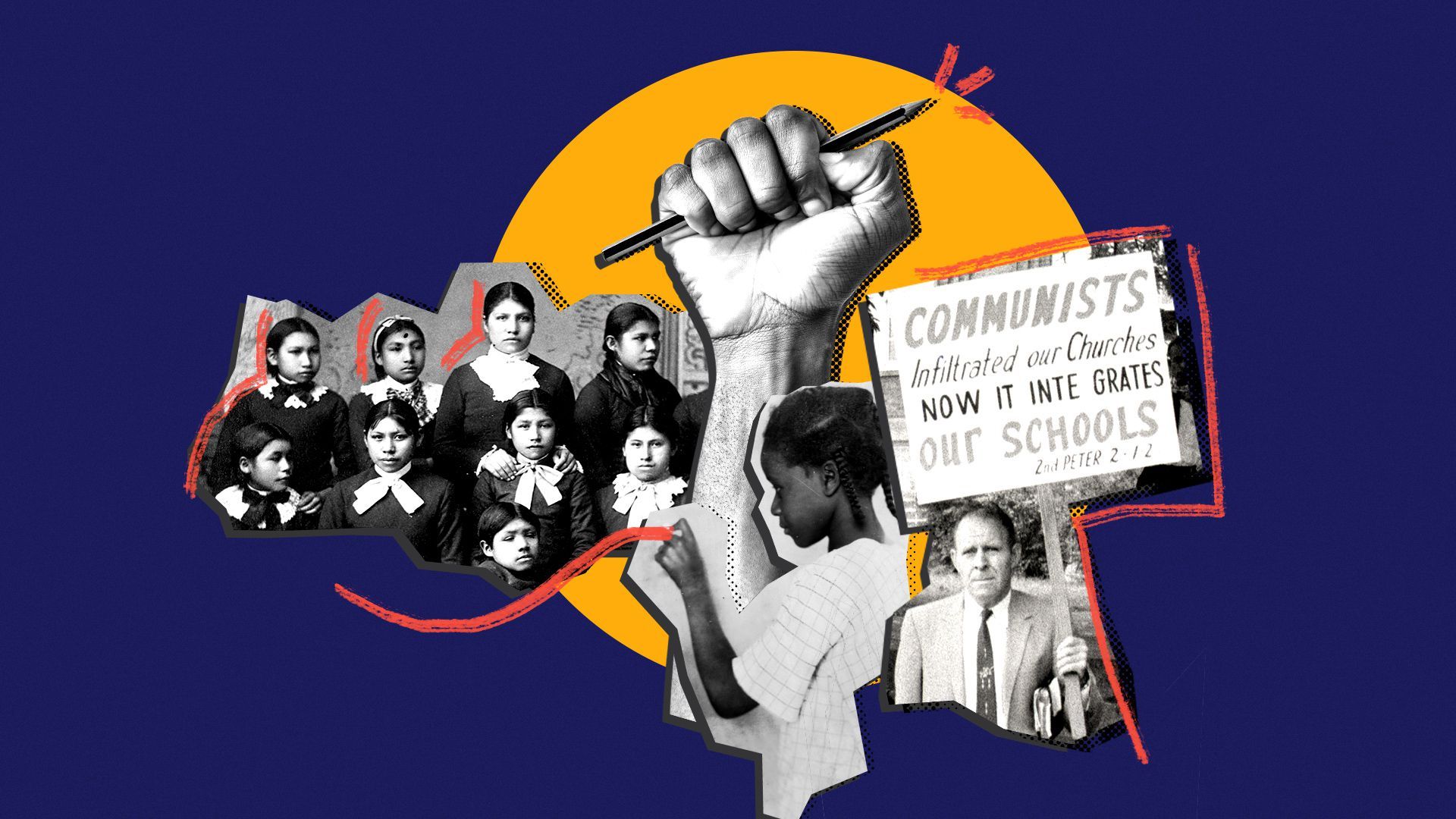

Smart Brevity™ count: 1,454 words ... 5½ minutes. | | | | | | 1 big thing: The failed promise of education |  | | | Photo illustration: Eniola Odetunde/Axios. Photos: Spencer Grant, George Rose, Stephen F. Somerstein/Getty Images | | | | In America, it's better to be born wealthy — which often means white — than to be born smart, Erica Pandey writes. Why it matters: For decades, the U.S. has held up schooling as the key to unlocking the American dream, but the facts tell us that education's promise is false. The big picture: Family income is perhaps the strongest determinant of student success, and low income becomes an even higher barrier when it intersects with race. - Even when Black students from poor families start kindergarten with above-median test scores, 63% test below the median by the time they're in the eighth grade, a recent Georgetown University study found.

- Among kindergartners in the same high-achieving, but lower-income category, nearly 2 in 5 Latino students, nearly 2 in 5 white students and 1 in 5 Asian students also saw lower scores over time.

- High-achieving students of color are too often overlooked by teachers and administrators: The odds of Black and Latino children being referred to gifted programs are 66% and 47% lower than white students, respectively, per the Fordham Institute.

Terence Fitzgerald, an education professor at the University of Southern California said: "If the silver bullet means education will give me the agency and resources to succeed, that it will give me power that is equal to a white man's, that is a lie." - "That will not happen. It hasn't happened for me."

What's happening: Decades of redlining and exclusionary zoning practices have segregated our neighborhoods and, by extension, our public schools. - The ZIP code in which you grow up determines what school you attend. And of the 10 million kids living in America's toughest neighborhoods — based on poverty rate, access to nutritious food, school quality and more — 4.5 million are Latino and 3.6 million are Black.

- There's a $23 billion school funding gap between districts serving mostly white students and districts serving mostly students of color.

Students of color — particularly Black students — are disproportionately disciplined at school, and disciplined more harshly, from a very young age. - Black students are overrepresented among students suspended from public schools by 22%, per a GAO report.

- Inconsistent school discipline can rapidly fray students' trust and engagement in school — and saddle them with delinquency records, fueling the school-to-prison pipeline.

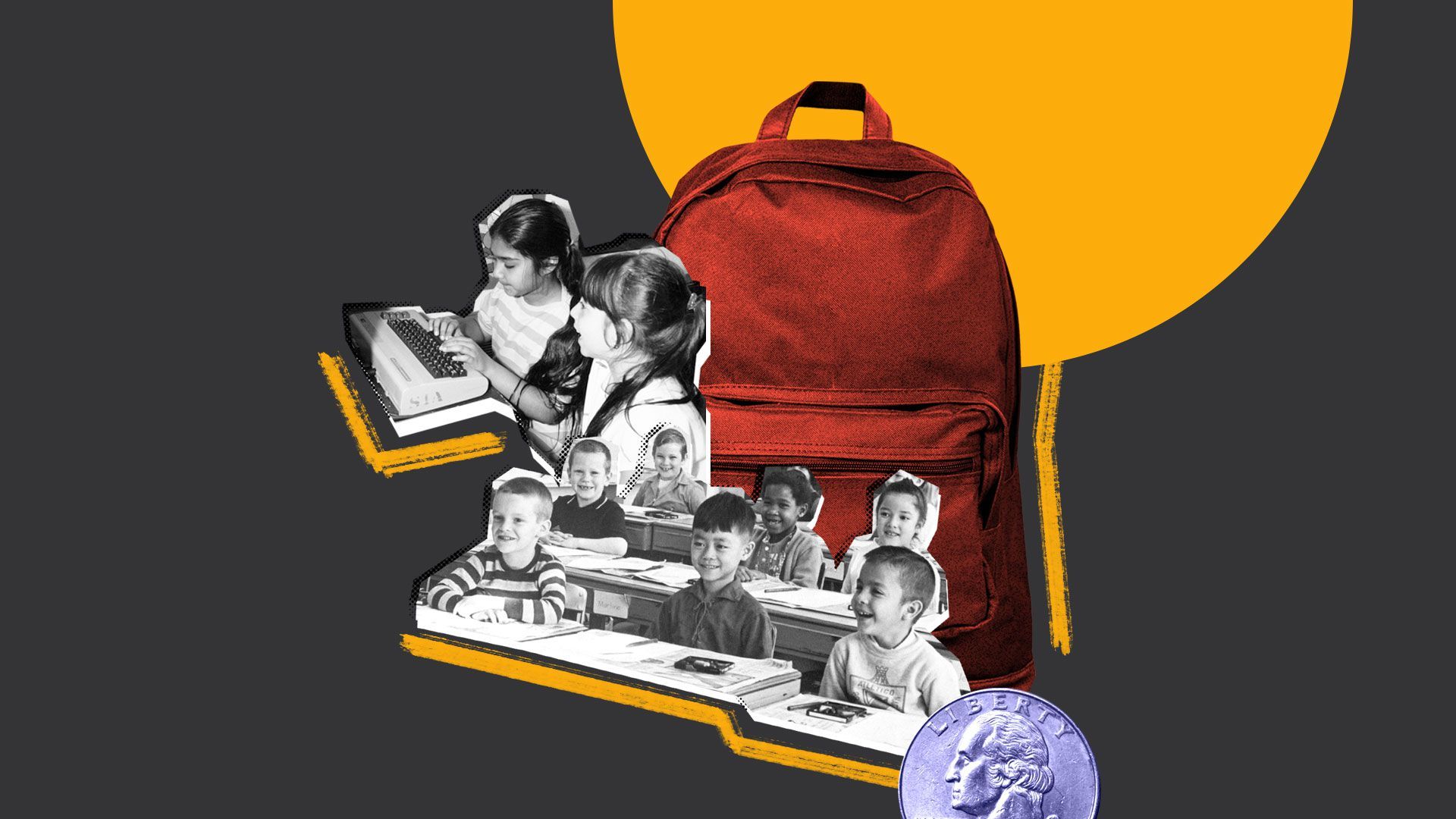

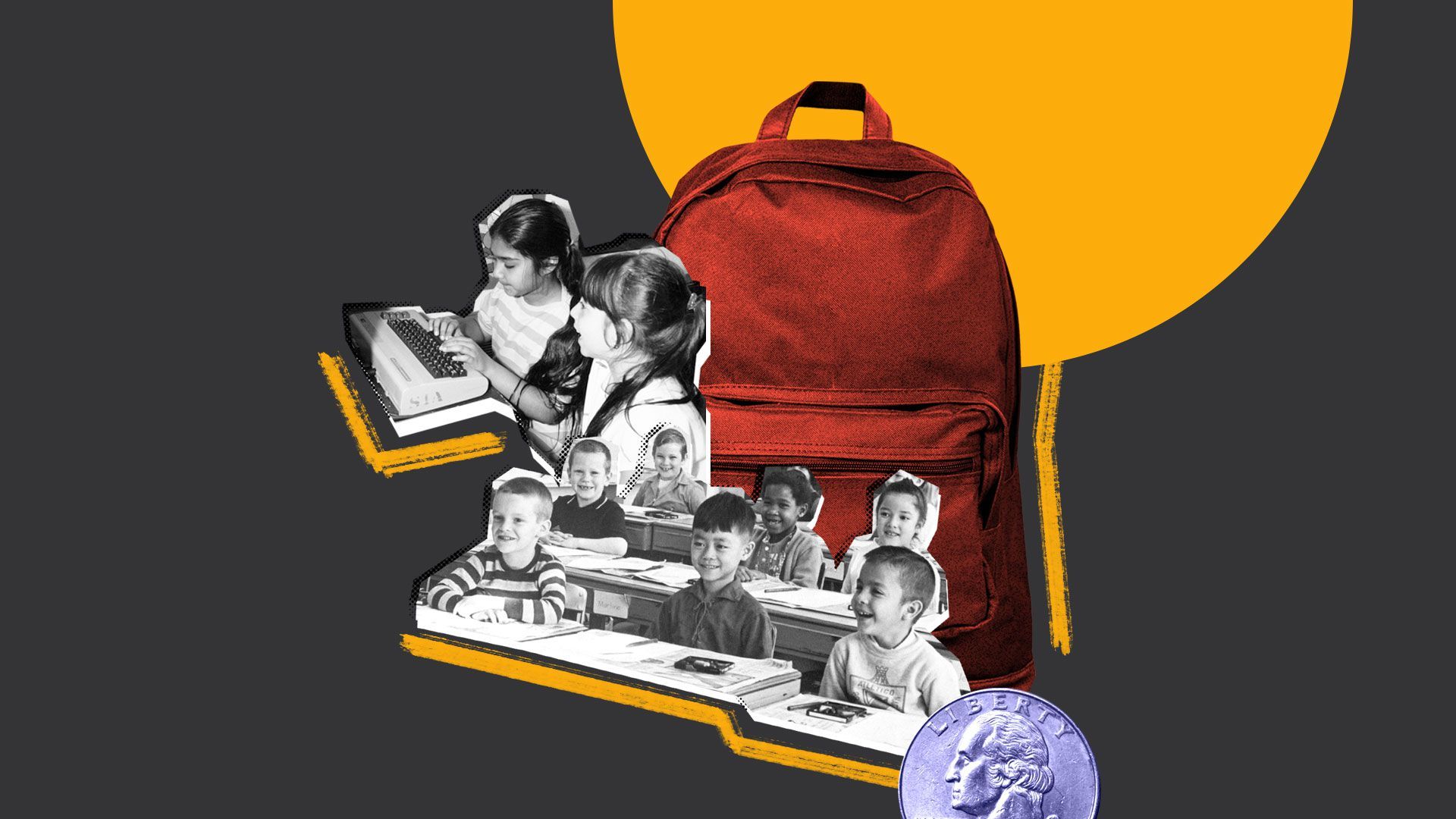

What to watch: The coronavirus pandemic has supercharged education's inequities, including access to broadband or to devices to connect to remote online classes. The bottom line: "The idea that this is about who's smart and who's not is just not true," says Anthony Carnevale, founder and director of Georgetown's Center on Education and the Workforce. "In the end, the system pretty much places you where you were as a child. Education is the problem. It is not the solution." |     | | | | | | 2. A history of unequal education |  | | | Photo illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios. Photos: Lewis W. Hine (Buyenlarge), Bettmann, Corbis/Getty Images | | |  Graphic: Naema Ahmed, Aïda Amer/Axios. Photos: Library of Congress, D. Corson/Classicstock, Bettmann, Ted Dully/The Boston Globe/Getty Images, growingintothemystery.net |     | | | | | | 3. Why neighborhood wealth matters so much |  | | | Photo illustration: Eniola Odetunde/Axios. Photos: Bettmann, Barbara Alper/Getty Images | | | | Property taxes help schools thrive, allowing districts with large, wealthy tax bases to offer their students better educational opportunities while leaving districts with smaller tax bases starved for cash, Courtenay Brown and Erica found. Why it matters: The gap plays an outsized role in perpetuating inequality in U.S. schools. Black and Latino students are likely to live in poorer neighborhoods and therefore attend poorer schools — shortchanging their education and producing consequences that snowball throughout K-12 and beyond. Between the lines: The U.S. is the only industrialized nation in the world where the wealth of your neighborhood plays a pivotal role in the quality of your public school education. - Restrictive housing policies, including redlining and property covenants that locked out Blacks, Latinos and Native Americans, led to segregated neighborhoods — and in turn, segregated schools — across the United States.

The big picture: A school district's budget determines everything from the quality of the teachers to the availability of after-school programs, honors courses and even the quality of lunch. - Better outcomes for lower-income students are directly linked to better funding for public schools, according to a study by Northwestern University and UC Berkeley.

The funding disparities can be vast, not only within states but sometimes in neighboring school districts. - One example: Detroit's public school district, which is 98% non-white, gets roughly $11,200 in local and state funding combined per pupil.

- Affluent Grosse Pointe sits across Mack Avenue to the southeast. Its schools are 75% white, and the district spends upwards of $3,000 more per student, according to an EdBuild analysis of the 2017-2018 school year.

How much money school districts get and how schools distribute those funds varies by state. - Some states make up the difference between what they determine to be adequate spending per student and what the property taxes cover in poorer districts.

- Still, it's rarely enough to close the funding gap between rich and poor schools. And state budget constraints often put this school funding at risk.

The pandemic has laid bare how poor schools have had to scramble to adjust to virtual learning, and how students are falling behind. - In poorer schools, many students share computers or laptops, said Darnisa Amante-Jackson, co-founder of Disruptive Equity Education Project.

- Wealthier public schools provide laptops and Wi-Fi hotspots.

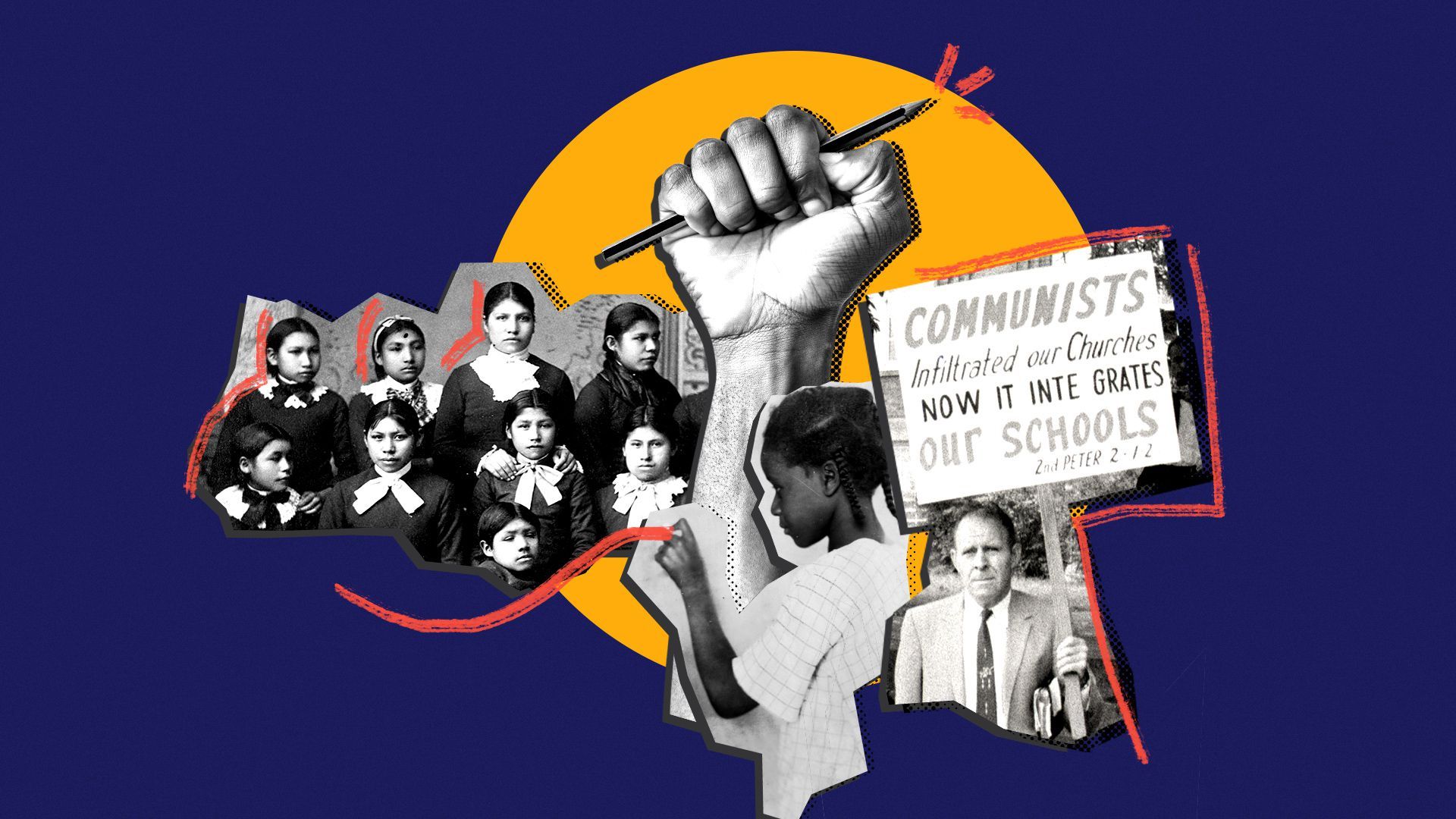

|     | | | | | | A message from Capital One | | Our commitment to growth in underserved communities | | |  | | | | The Capital One Impact Initiative is supporting socioeconomic mobility through a $200 million, five-year commitment to closing gaps in equity and opportunity. Read about our focus on creating a world where everyone has an equal opportunity to prosper. | | | | | | 4. A reckoning with teaching race and history |  | | | Photo illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios. Photos: Library of Congress, Warren K Leffler/Getty | | | | American history classes have failed to represent the experiences that children of color live, leaving some students struggling to see themselves or their cultures as part of America, Marisa Fernandez and Maria Arias report. Why it matters: Accurate historical teachings on slavery, indigenous peoples and immigration help all students understand how people of color have shaped American society. Ethnic studies courses can narrow the learning gap and boost the academic performance of some students of color at risk of dropping out, experts say. - "We don't want to make villains out of people, and at the same time history should be honest," said Leilani Sabzalian, who is Alutiiq and an assistant education professor at the University of Oregon. "History should account for people's lived experiences."

- A new Axios-Ipsos poll finds 68% of Americans think racism should be taught as part of U.S. history lessons, and a majority of Americans say there was "not enough" teaching in their school about the contributions of non-European Americans to our history.

Driving the news: The summer's racial justice protests have moved students and education professionals to examine the historical inconsistencies in textbooks and the singular perspective in school curriculums. - Neither states nor the Education Department requires or recommends expanding history beyond the contributions of European descents, the Southern Poverty Law Center found.

- Lessons on the "first Thanksgiving," for example, mention pilgrims but don't identify the Wampanoag tribe as the Native Americans who attended the feast, or detail their relationship to the pilgrims.

- High school AP classes emphasize European history, with little mention of the contributions of other parts of the world.

The bottom line: Students exposed to courses that examine the roles of race, nationality and culture had better academic performance and a better sense of their own identity. |     | | | | | | Bonus images: In the steps of history |  | | | Via @the_female_lead | | | | Sixty years ago today — on Nov. 14, 1960 — Ruby Bridges put an end to segregation at the all-white William Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans (left). Sixty years after that, Vice President-elect Kamala Harris becomes the first Black woman elected to the nation's second-highest office. |     | | | | | | 5. Poll: Views on education equality |  Data: Axios/Ipsos poll (±2.4% margin of error). Chart: Andrew Witherspoon/Axios A strong majority of Americans say our public education system is unequal, and half say the nation's schools aren't well equipped to help children of all races and ethnicities succeed, according to a new Axios-Ipsos survey. Go deeper. |     | | | | | | 6. Unequal resources outside the classroom |  | | | Photo illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios. Photo: Brooks Kraft LLC/Getty Images | | | | Families have come to heavily rely on schools to help them meet challenges ranging from poverty and discrimination to societal pressures to succeed, Marisa writes. The big picture: Black, Latino and Native American students need different kinds of support beyond the classroom to do well in school and for sound emotional development into adulthood. By the numbers: 14 million students are in schools with no counselor, nurse, psychologist or social worker, according to the ACLU. - Associations recommend at least one counselor and one social worker for every 250 students, at least one nurse for every 750 students, and one psychologist for every 700 students. Few states meet this guidance.

Why it matters: Students in schools that have health care, counseling, career guidance and devices to cope with stress are more likely to have higher graduation rates and fewer school absences. - Although research has shown the racial achievement gap is slowly improving, the resources for social-emotional support are inconsistent by ZIP code.

Black, Latino and Native American students are more often in the presence of school resource officers than counselors or mental health professionals and more likely to face exclusionary discipline in schools. - "In the past couple of decades we've seen this push toward law and order and mass incarceration that has been from communities with fewer resources," said Khalilah Harris, managing director of K-12 education policy at the Center for American Progress.

- A new Axios-Ipsos poll finds just a third of white Americans say they had police or safety officers at their school, compared with nearly half of Hispanic/Latino Americans who say the same, and 45% of Black Americans.

The bottom line: Now more than ever, schools are considered key intervention centers to help students succeed beyond graduation. |     | | | | | | A message from Capital One | | Creating a revolution of diversity in tech | | |  | | | | Capital One associates are mentoring Fellows at Pursuit — a four-year program that trains adults from underserved backgrounds with no prior experience in programming. Read more about how Capital One Associates helped 20 Pursuit Fellows create their first iOS apps. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1300, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment