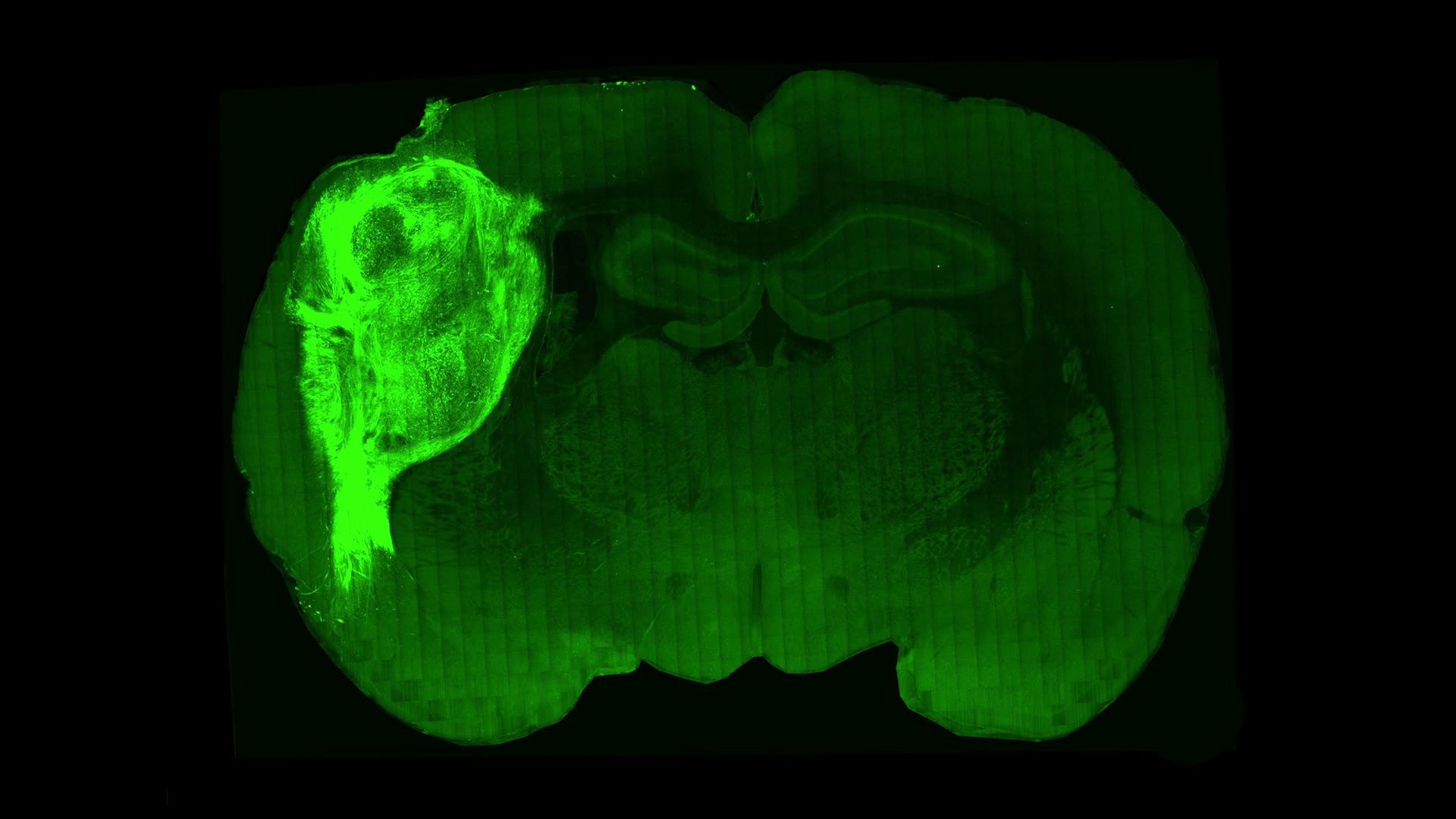

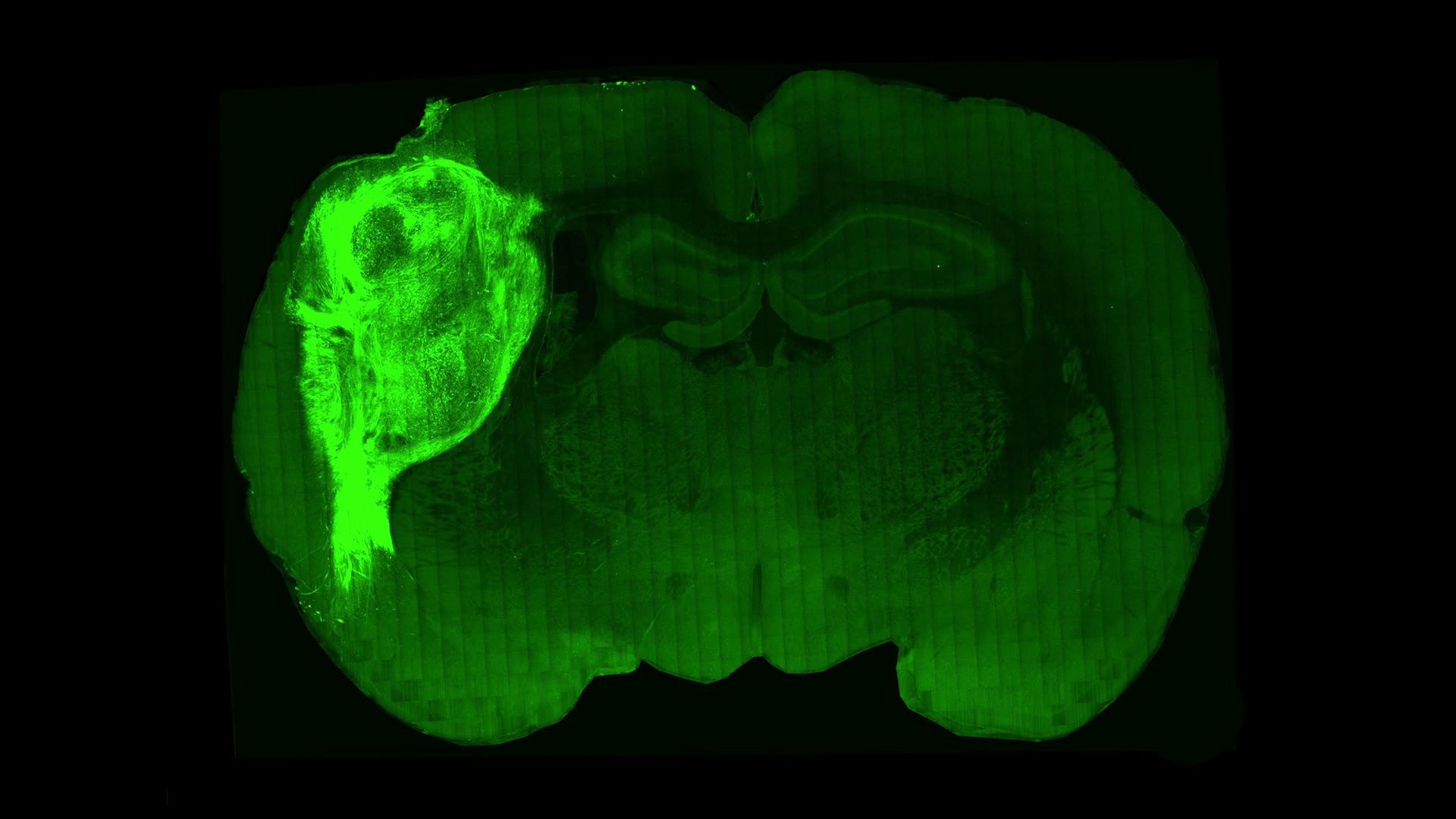

| | | | | | | | | | | Axios Science | | By Alison Snyder · Oct 13, 2022 | | This week's newsletter is 1617 words, about a 6.5-minute read. | | | | | | 1 big thing: Human cells in rat brains are new tool to study disease |  | | | A transplanted human organoid labeled with a fluorescent protein in a section of the rat brain. Credit: Stanford University | | | | Lab-grown clusters of human neurons transplanted into the brains of young rats and connected to their brain circuitry offer a new way to study the human brain, researchers reported this week. Why it matters: The living human brain is largely inaccessible to scientists, hindering the study of autism spectrum disorders, schizophrenia and other conditions. - The approach is "a step forward for the field and offers a new way to understand disorders," Madeline Lancaster, a developmental biologist at the Medical Research Council's Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, U.K., told me in an email. Lancaster developed brain organoid techniques but wasn't involved in the new research.

How it works: Brain organoids are clumps of cells a few millimeters in diameter that are made from stem cells that develop into neurons. - Organoids made from human cells offer scientists a model that's more similar to the human brain than animal models, like rats.

- But organoids in a dish can only develop so much. Without the blood vessels that support living cells, the neurons stop growing and they don't form circuits, leaving the organoids far less complex than the human brain and limiting what scientists can glean from them about brain disorders.

- Scientists have tried to take advantage of an animal's more complex environment to create more sophisticated organoids: when they are transplanted into adult rats, previous research has shown organoids continue to mature.

What's new: Scientists led by neurobiologist Sergiu Paşca at Stanford University transplanted organoids — about 1 to 1.5 millimeters in diameter — into the developing brains of young rats. - After three months, individual neurons grew larger than they did in a dish and the organoids grew to about nine times the size they were when they were implanted, covering about one-third of the rat's brain hemispheres, the team reported this week in the journal Nature.

- The human neurons and rat neurons began to form connections, which didn't affect the behavior of the rats.

- The researchers then tested whether the human neurons integrated into the rat brain circuitry by blowing air at the rat's whiskers. They found the human neurons were active in response.

In another experiment, the researchers demonstrated that the human neurons can also drive the rat's behavior. - A technique called optogenetics was used to activate the human neurons in rats when they drank from a water bottle (a reward).

- Over time, the rats began to go to the water bottle when the neurons were activated. Rats that didn't have the transplant, or whose human neurons weren't turned on, didn't drink from the bottle.

The impact: Paşca and others aim to use organoids to study brain disorders. - The team transplanted cells from patients with Timothy syndrome, a rare genetic disease, and saw defects in the neurons as they grew, which hadn't been seen in organoids that weren't transplanted.

- "We have a moral imperative to find better models to study these conditions, and tackling difficult conditions such as psychiatric disorders will require bold new approaches," Paşca said in a press conference.

What's next: "There are interesting possibilities when you are looking at this general model for repairing the brain after some injury," says neurosurgeon Isaac Chen from the Presbyterian Medical Center of Philadelphia, who studies brain organoid transplantation. - A first step would be to see whether transplanted organoids could be integrated into an animal with an injury, he adds.

The big picture: Brain organoid research brings ethical and legal concerns, along with debates about the limits of the research. - As of now, organoids still aren't organized like human brain tissue, and "putting human organoid-derived cells in the brain [of an animal] does not in any way make their consciousness human," says Jeantine Lunshof, a bioethicist at Harvard University who studies the ethics of organoids.

- A current concern, though, is whether organoids might be transplanted to non-human primates. Paşca says there is no need: "It's not something that we would do or that I would encourage doing."

|     | | | | | | 2. The wildlife populations in peril |  Data: WWF; Chart: Jared Whalen/Axios Populations of mammals, birds, fish, reptiles and amphibians around the world declined an average of 69% between 1970 and 2018, according to a new report. Why it matters: Knowing where populations are declining helps conservationists identify "where actions will have the most impact to protect species," says Rebecca Shaw, chief scientist at the World Wildlife Federation (WWF), which published its latest biennial Living Planet report on the state of biodiversity this week. How it works: The Living Planet Index (LPI) used in the report measures how populations of vertebrates — not the number of individuals of a species — change over time. By the numbers: The LPI tracked almost 32,000 wildlife populations of 5,200 vertebrate species around the world. - The index revealed the world's wildlife populations declined an average of 69% over the past 50 years.

- Fish, frogs and other freshwater vertebrate species populations declined by an average of 83%.

- In Latin America and the Caribbean, where swaths of land are being developed for food systems and mined, wildlife populations fell by an average of 94%.

Between the lines: The index only reflects species that are being monitored, and there are gaps in data about fish and reptiles in the tropics. - About 11,000 of the populations tracked in the LPI are new to the report this year — most of them from the global south.

- Biodiversity data from the region is sparse and researchers working on the LPI combed through non-English scientific literature to improve representation of wildlife, Shaw says.

Yes, but: The index has its limitations. For instance, a small number of declining populations can exaggerate the overall global LPI. - When the authors recalculated the figure by removing populations with extreme increases or decreases, however, the average decline was still steep.

- An average decline in species population sizes can also mask good news about increases in individual wildlife populations. The report says about half of the populations monitored are stable or increasing.

- Populations of loggerhead turtles in Cyprus, the common crane in the U.K., and mountain gorillas in Rwanda, Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo have all grown.

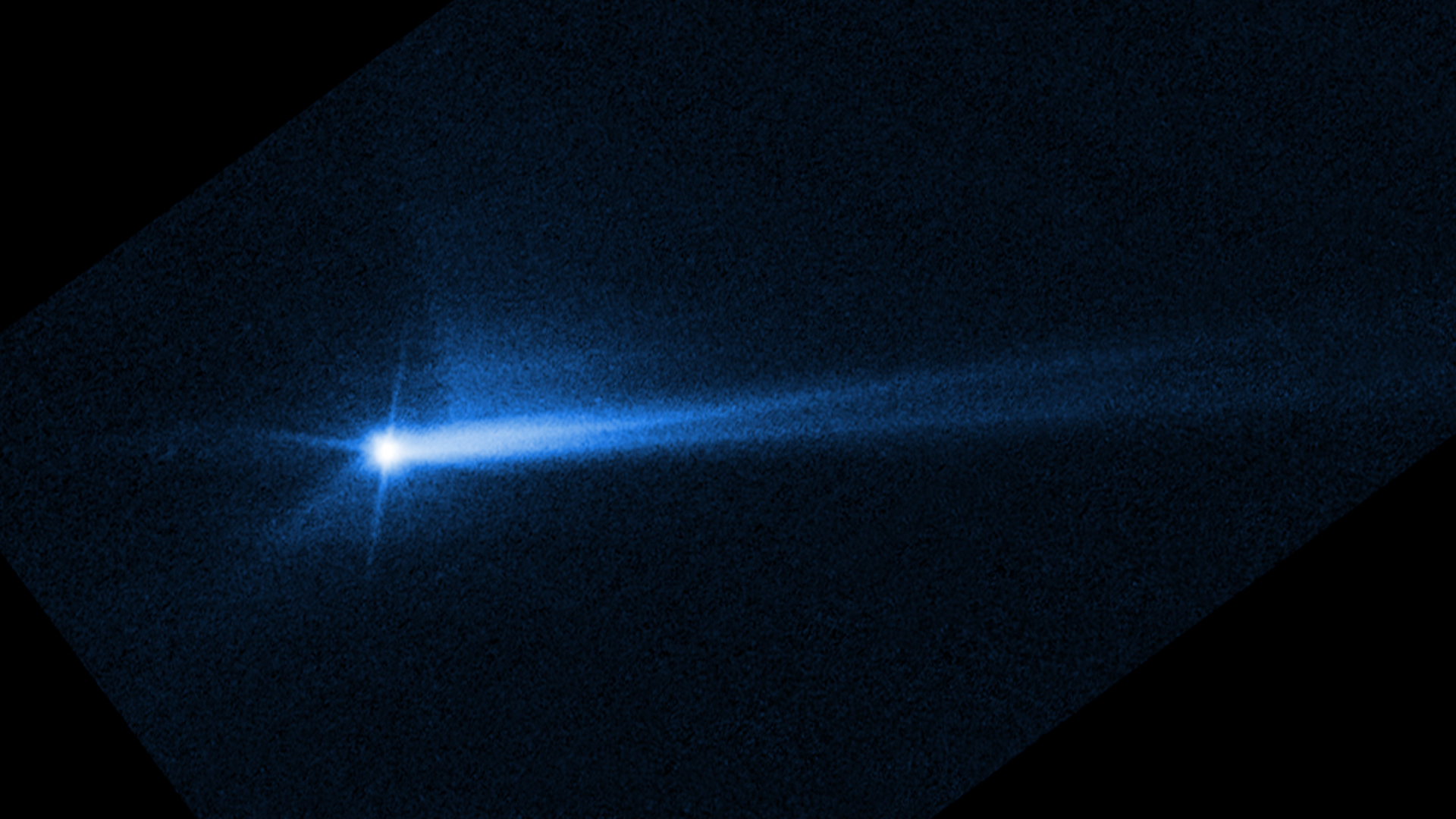

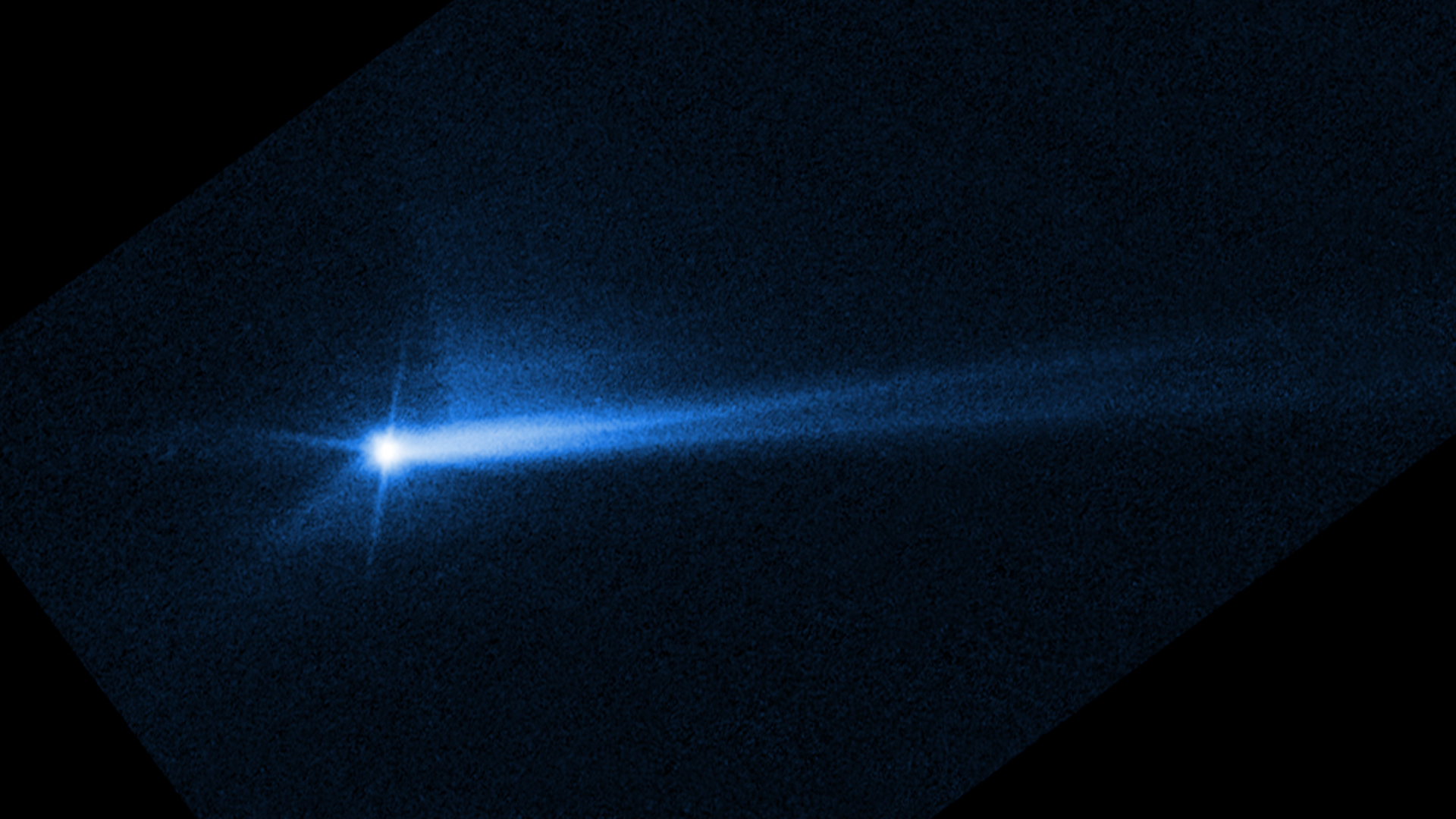

What to watch: Targets for preserving biodiversity will be set at the UN Biodiversity Conference in December. |     | | | | | | 3. NASA's DART mission deflects an asteroid |  | | | Debris blasted off of the asteroid Dimorphos as seen by the Hubble Space Telescope. Photo: NASA/ESA/STScI/Hubble | | | | A NASA mission to change the orbit of an asteroid in deep space successfully deflected its asteroid target, the space agency confirmed this week, Axios' Miriam Kramer writes. Why it matters: The Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) was designed to test the technology needed to throw a dangerous asteroid off-course with Earth if one is ever found. Catch up quick: DART slammed into the small asteroid moonlet Dimorphos on Sept. 26 in a bid to change its path around the larger asteroid Didymos. - NASA announced Tuesday that observations from ground and space-based telescopes found DART's impact changed the orbit of Dimorphos around Didymos, shortening it by about 32 minutes and effectively taking it off its normal course.

- The test would have been considered a success if it had just changed the orbit of Dimorphos by 73 seconds.

- It took a couple weeks for scientists to gather enough data to figure out just how much the moonlet's orbit had changed.

The big picture: NASA and other space agencies around the world are focused on finding and tracking potentially dangerous asteroids that could impact Earth sometime in the future. - "This is a planet wide issue," Lori Glaze, the director of planetary science at NASA, said during a press conference Tuesday. "If there were an asteroid that were a threat to Earth, we should all be concerned and we all need to be working together."

- Scientists are now working to develop the Near Earth Object Surveyor telescope, a space-based observatory that will be able to detect difficult-to-find, possibly dangerous space rocks.

- That mission, however, has been delayed until 2028 due to a major budget cut.

|     | | | | | | A message from Axios | | Business news worthy of your time | | |  | | | | Together, Axios Markets, Axios Macro, and Axios Closer decipher what the daily deluge of news, statistics, and analysis really means — and why it matters. Subscribe for Free | | | | | | 4. Worthy of your time |  | | | A parrotfish scrapes off and eats turf algae from coral skeletons at Millennium (Caroline) Atoll. Photo: Enric Sala/National Geographic | | | | Once devastated, these Pacific reefs have seen an amazing rebirth (Enric Sala — National Geographic, paywall) Oh what a hangled web we weave (Lilly Sullivan — This American Life, with a h/t to my friend MK) The vital crosstalk between brain and breath (Greg Miller — Knowable) |     | | | | | | 5. Something wondrous |  | | | Pong controlled by a layer of neurons in a dish. Credit: Kagan et al - Neuron | | | | Neurons can play Pong, a team of scientists reported this week. Why it matters: The researchers say the experimental setup is a new way to study how the brain works and to potentially better understand epilepsy and other diseases. How it works: Researchers at the Melbourne-based startup Cortical Labs grew mouse and human neurons on a "DishBrain"— an array of electrodes that can read the electrical activity of the neurons to move the paddle. - It can also deliver an electrical pulse to the cells that provides feedback — in under 5 milliseconds — that the neuron was hitting the ball.

- The 800,000 neurons learned to play within 5 minutes — and, as time went on, rallied longer.

- Human neurons could rally longer than mouse neurons.

The neurons "can adjust firing activity in a way that suggests the ability to learn to perform goal-oriented tasks," the team wrote in the journal Neuron. - They term it "synthetic biological intelligence" — but not everyone is convinced, Dan Robitzski writes in The Scientist.

The big picture: "The results shouldn't be surprising, because neurons are built to process information," says Brett Kagan, chief scientific officer at Cortical Labs. - Generalized intelligence — a major goal for AI researchers — comes from neurons. The team at Cortical wants to develop next-generation computer chips that harness neurons' computational power.

- "So, it's not that wild, and at the same time, it is quite exciting," he says.

What's next: The team plans to treat the neurons with ethanol and medicines to see their effect, and to use the system to try to find "insights into the cellular correlates of intelligence," they say in the paper. |     | | | | | | A message from Axios | | Business news worthy of your time | | |  | | | | Together, Axios Markets, Axios Macro, and Axios Closer decipher what the daily deluge of news, statistics, and analysis really means — and why it matters. Subscribe for Free | | | | Big thanks to Laurin-Whitney Gottbrath for editing this week's newsletter, to Jared Whalen on the Axios visuals team and to Nick Aspinwall for copy editing this edition. |  | | Are you a fan of this email format? It's called Smart Brevity®. Over 300 orgs use it — in a tool called Axios HQ — to drive productivity with clearer workplace communications. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters. If you're interested in advertising, learn more here.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment