| | | | | | | Presented By PhRMA | | | | Axios Science | | By Alison Snyder · Jul 14, 2022 | | Thanks for reading Axios Science. This week's newsletter is 1,820 words, about a 7-minute read. - Send your feedback and ideas to me at alison@axios.com.

- Sign up here to receive this newsletter.

- This newsletter will be summering for the next six weeks. We'll return on Aug. 25 when my colleague Eileen Drage O'Reilly will be at the helm. I'll be back in your inbox the following week.

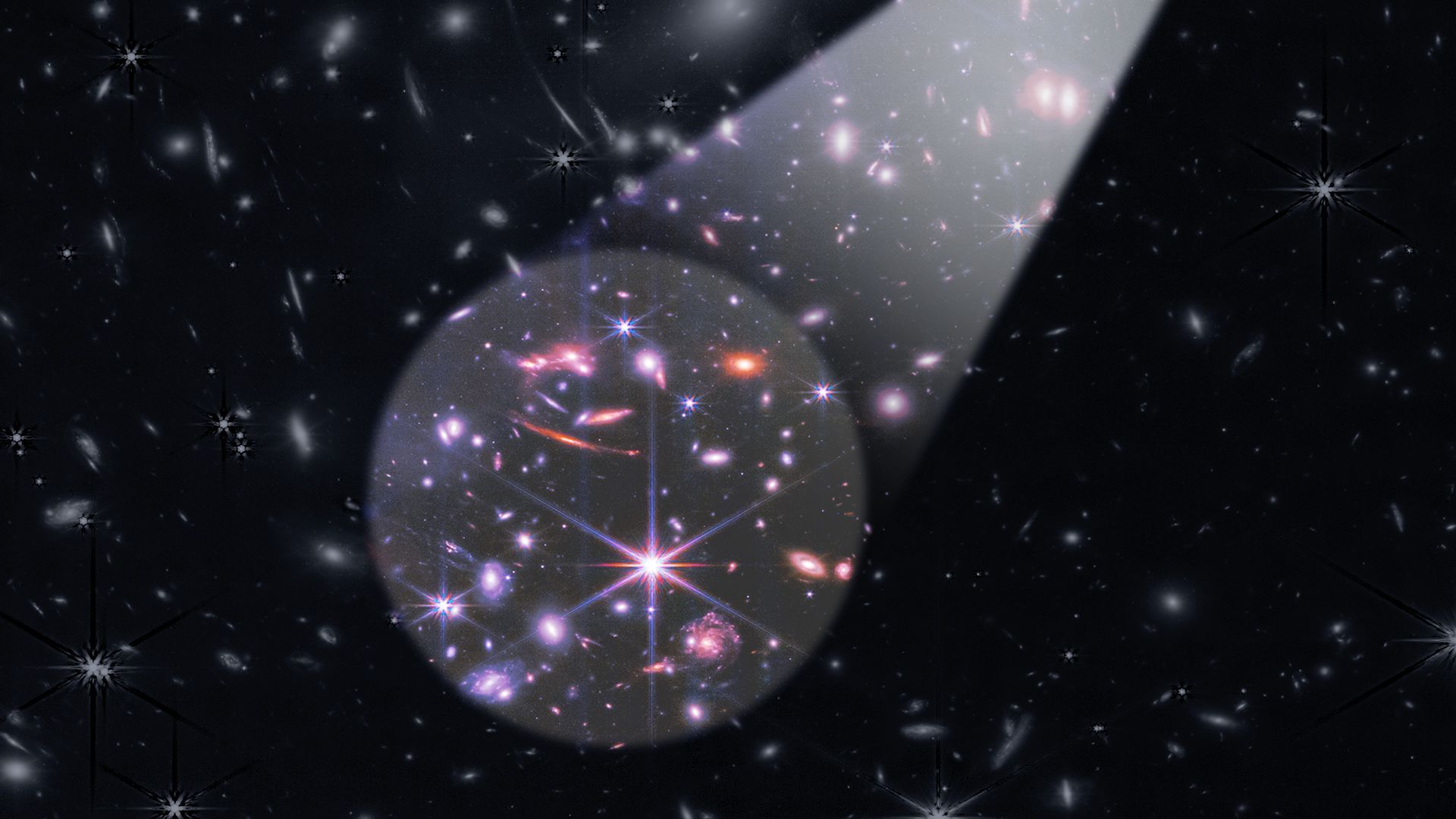

| | | | | | 1 big thing: Astronomers search for light from the earliest galaxies |  | | | Photo illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios. Photo: NASA, ESA, CSA, and STScI | | | | Features of some of the earliest galaxies in the universe are coming into sharper focus, my Axios colleague Miriam Kramer and I write. The big picture: Data from telescopes in space and on Earth — including the powerful new James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) — will give astronomers their best shot yet of figuring out how the first stars and galaxies in the universe formed and evolved. - The several hundred million years after the Big Bang are a mysterious and critical moment in the cosmos. During that time, the first stars were born from gas largely made of hydrogen and helium. Those stars died and produced heavier elements that were strewn across the universe, seeding the next generation of stars.

- One billion years after the Big Bang, galaxies and supermassive black holes existed across the universe. The universe was also reionized by then, transforming it from a place filled with dark, dense primordial gas into a place where light could shine.

- Astronomers want to know what role the first stars and galaxies played in that critical process — and how these early astronomical objects came to be.

Driving the news: NASA released a stunning image showing thousands of galaxies — some of which formed less than 1 billion years after the Big Bang — this week as part of the JWST's first five scientific photos. - The telescope is also designed to piece together the elements that made up the earliest galaxies to understand their evolution.

- "This is how the oxygen in our bodies was made — in stars in galaxies. And we're seeing that process get started," says Jane Rigby, an astrophysicist at NASA's Goddard Flight Center and the operations project scientist for JWST.

How it works: JWST looks at the universe in infrared (IR) light, giving astronomers access to distant stars and galaxies that emit light typically obstructed by cosmic dust. - As the universe expands, the wavelength of optical light from early galaxies increases and is shifted into the IR spectrum as it moves through space and time. These galaxies are too faint for us to see with the naked eye, but they can still be captured by the lenses and detectors of sensitive telescopes.

- Data from JWST will be combined with optical observations from the Hubble Space Telescope, radio data from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) and the Very Large Array (VLA) telescopes, and measurements from the Chandra X-ray Observatory to give scientists a more holistic view of the universe.

The big question: In combining that data, astronomers are searching for clues about how the first galaxies ever formed. |     | | | | | | 2. First galaxy clues | | One theory suggests early galaxies were born from massive clouds of gas and dust that collapsed in on themselves, creating dense clouds that began to coalesce and spin — forming galaxies. - Another theory, supported by Hubble data, says smaller masses of gas and dust merged to form larger galaxies and clusters bound together by immense gravity.

- Mounting evidence points to mergers as the dominant way galaxies grow but observations are still sparse and the details aren't clear.

- "Galaxy formation is just a messy process," says Chris Carilli, a radio astronomer who works on the National Science Foundation's ALMA observatory and studies early galaxy formation.

- "[It's] more like weather," he says. Like studying clouds, the goal is to identify essential physical phenomena seen across galaxies and separate them from the details of an individual galaxy to understand when and how the universe turned primordial gas into stars.

Between the lines: About 10 billion years ago, the mass of galaxies appears to have been dominated by gas rather than stars, according to data from ALMA. In newer galaxies, the opposite is true. - This molecular inventory provides clues about how galaxies — and their star-forming activities — change over time. The rise and fall in the amount of gas in galaxies over the history of the universe parallels the rate at which stars were formed in them, Carilli says.

Where it stands: Scientists were able to use the JWST to parse out the molecules — including oxygen, neon and hydrogen — that made up one of the galaxies in this week's deep field image as it existed 13.1 billion years in the past. - "The spectra are the astronomer's equivalent of the DNA swabs," tweeted Jonathan McDowell, an astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. "What the galaxies were up to is encoded in their light."

What to watch: Comparing the properties of gas in galaxies near and far can help astronomers study how the interstellar medium itself changed over time. - "I think we'll be able to better understand that evolution in the coming years, especially with JWST," says Bryan Terrazas, an astrophysicist and postdoctoral fellow at the Center for Astrophysics.

|     | | | | | | 3. Catch up quick on COVID | | "New hospital admissions of patients with COVID-19 are on the rise in the U.S., topping 31,000 over a seven-day average ending July 11," Axios' Tina Reed reports from CDC data. The FDA this week authorized Novavax's COVID vaccine "voicing hope that the availability of a more traditional vaccine might help convince those skeptical" of mRNA COVID vaccine technology to get vaccinated, Matthew Herper writes in STAT. A new Omicron subvariant was detected in Shanghai, per Reuters. |     | | | | | | A message from PhRMA | | What's fueling inflation? | | |  | | | | Not prescription drugs — and the presidential administration's economic data proves it. The proof: Overall inflation surged by 8.6% since May 2021 while prices for medicines grew less than 2%, even before factoring in the discounts insurers receive. Find out more. | | | | | | 4. Monkeypox update |  Data: CDC; Chart: Erin Davis/Axios Visuals The federal and state response to the escalating monkeypox outbreak is lacking access to enough vaccines, testing and treatments to keep up with the virus' spread, infectious disease experts are warning, Axios' Eileen Drage O'Reilly and Erin Davis report. Why it matters: Public health officials are racing to halt the spread before the disease becomes endemic in more countries. Cases are rising quickly — New York City, for example, has seen a tripling in patients over the past week. - Globally, there are now more than 11,000 patients — with 336 in New York City alone — and "a lot of cases that are not being diagnosed," NYC Department of Health's Mary Foote said today at a news briefing held by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

The big picture: Some experts say this outbreak echoes the start of the HIV epidemic that also first appeared in communities of men who have sex with men (MSM), but NIAID director Anthony Fauci says there are "fundamental differences" from that traumatic time when there was an unknown agent killing patients rapidly. - While this outbreak of monkeypox outside endemic countries is "unprecedented" in its rate of human-to-human spread, the virus for monkeypox has been identified, isn't nearly as deadly, and there are potential vaccines and treatments already in existence, Fauci tells Axios.

- "The challenge, now, is to obviously get a handle on the extent of this and the spread of this, and you do that by testing," Fauci says.

- "The other challenge is to implement the countermeasures we already have. Like getting the vaccines to the people at risk and to make sure that we mobilize the vaccines we contracted to be made years ago," he adds.

The latest: The CDC has now partnered with five commercial firms to make testing more widely available, but there's concern it hasn't reacted quickly enough. - The FDA approved in 2019 the Jynneos vaccine for adults at high risk of monkeypox to Bavarian Nordic A/S, but there are not enough doses to distribute, Foote says. CDC press officer Scott Pauley says the CDC and HHS have delivered more than 41,000 doses of the vaccines as of July 7.

- While there's an effective antiviral treatment called TPOXX, which is FDA-approved for smallpox, it's only available for use in certain monkeypox patients via an onerous 120-page protocol for expanded access to investigational new drugs, which is a big barrier to access, Foote says. (FDA declined to "confirm, deny or comment" to Axios on "potential/pending applications.")

"We're worried that this could become a treatment only accessible by patients with privilege or who are very savvy at navigating a very complicated system," Foote says. Read more and check out the interactive map. |     | | | | | | 5. Worthy of your time | | First person dosed in novel gene editing clinical trial (Amanda Heidt — The Scientist) Hawai'i law could break years-long astronomy impasse (Alexandra Witze — Nature) DeepMind AI learns simple physics like a baby (Davide Castelvecchi — Nature) |     | | | | | | 6. Something wondrous |  | | | An insect in Amazonia, Brazil, in December 2015. Photo: Christophe Simon/AFP via Getty Images | | | | The orchestra of sounds produced by animals can be used to measure how many species are present in the Amazon, according to a recent study. Why it matters: These "acoustic fingerprints" of animal communities could help researchers better understand the long-term consequences for species threatened by logging and fire, the researchers write in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. - The study site in the Amazon is "a frontier zone where expanding agricultural commodities are coming up against the last vestiges of intact forest in this region," says Danielle Rappaport, who was a co-author of the study as a graduate student at the University of Maryland.

- Drought, fires and logging have taken sections of forest, leaving a fragmented home for its inhabitants.

Changes in the forest are typically measured by satellites from space and by Lidar flown on planes, which can be used to estimate the amount of carbon (in the form of trees) to get a better representation of the forest under the canopy. - But, "the ability to observe animal communities is limited," says Rappaport, who is now chief research and innovation officer at Amazon Investor Coalition, a platform she co-founded to address the economic pressures that drive forest degradation.

- The bioacoustic approach allows scientists to get a picture of animal communities without having to identify individual animals.

How it works: Frogs, insects, mammals and birds all produce sound. The collective soundscape of different species varies by the time of day and includes a range of frequencies. - It's like an "animal orchestra," Rappaport says.

- The researchers dropped sensors into 39 degraded forest areas in the southern Brazilian Amazon to record the daily soundscape. They collected 214 full-day records in total.

- They then combined the recordings with satellite imagery and data about how long ago the associated area of forest was degraded, whether there had been a single fire or multiple ones, the intensity of the degradation and other conditions.

What they found: They expected the sounds of birds to be the most important markers of forest intactness but it was the insect orchestra, especially at midday and during the night, that gave the best measure of biodiversity in an area, they reported. - That was true in both logged and burned forests.

But the orchestra was different — quieter and less diverse — in forests burned multiple times compared to forests that burned once or were logged. - When an area is logged, though, some insect instruments in the orchestra were temporarily lost. They came back over time.

What to watch: There are now solar-powered acoustic sensors that Rappaport says could be used to transmit data in real-time. "Now the vision of having ecosystem weather stations that can tell us what birds, mammals and bats are present is viable." Listen to an insect orchestra in the Amazon. |     | | | | | | A message from PhRMA | | The real root of inflation | | |  | | | | Some policymakers are blaming the cost of prescription medicines for the rise of inflation to build support for harmful policies. What you need to know: Medication affordability is key, but the fact is that prescription drugs are not fueling inflation. Learn what drives up costs for patients. | | | | Many thanks to Miriam, Eileen and Erin for contributing to this week's newsletter, to Laurin-Whitney Gottbrath for editing, to Aïda Amer on the Axios Visuals team and to Carolyn DiPaolo for copy editing this edition. |  | | Are you a fan of this email format? It's called Smart Brevity®. Over 300 orgs use it — in a tool called Axios HQ — to drive productivity with clearer workplace communications. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters. If you're interested in advertising, learn more here.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment