| | | | | | | Presented By 3M | | | | Axios Science | | By Alison Snyder · Jun 16, 2022 | | Thanks for reading Axios Science. This week's newsletter is 1,194 words, about a 5-minute read. | | | | | | 1 big thing: Polar bear discovery raises cautious hopes |  | | | A polar bear stands on a snow-covered iceberg that is surrounded by fast ice, or sea ice connected to the shore, in southeast Greenland in March 2016. Photo: Kristin Laidre/University of Washington | | | | A previously unknown group of polar bears in southeast Greenland is living in an environment with relatively little sea ice, potentially pointing toward a way to preserve some of the iconic species as Arctic sea ice melts, my colleague Andrew Freedman and I write. Why it matters: The research suggests polar bears can live in a wider variety of conditions than scientists previously thought — and, some scientists say, raises the possibility that some groups of polar bears in select locations could be more resistant to global warming's sweeping changes. - However, many questions remain to be answered about the newly identified population and its ability to withstand rapid Arctic climate change.

Driving the news: The newly discovered group of polar bears lives among the isolated fjords and glaciers of southeast Greenland. - Researchers tracked the group — which they say likely contains a few hundred bears — using satellite data and ground-based tracking devices. They published their findings today in the journal Science.

Polar bears typically use sea ice that freezes along the coastlines as their hunting ground to catch seals. But that ice is absent for more than 250 days each year in southeast Greenland. - During stretches when they don't have access to sea ice, polar bears typically move to land or head to other areas where they can find sea ice.

- But this newly discovered group was able to stay put and keep hunting, relying instead on freshwater ice from glaciers.

The intrigue: The study's authors say the population offers a window into how some animals might fare as climate change continues to transform the Arctic, where temperatures are increasing about three times as fast as the rest of the world. - "[S]ome polar bears can become established and adapt to this distinctive environment, which, in some areas, may provide a buffer to sea-ice loss," the authors write.

- The newly discovered population could provide a focus for polar bear conservation efforts, similar to how ecologists are seeking out hardier coral species that can better withstand marine heat waves.

But, but, but... The ice these bears rely on is also under threat. It may offer these bears a hunting ground now, because sea ice is disappearing first, but Greenland's glaciers are melting. - "These bears are subject to the same climate warming as all other polar bears," lead author Kristin Laidre of the University of Washington told Axios in an interview.

- Whether polar bears use sea ice or ice from glaciers, "the general contours of the story are the same — climate change melt and ice retreat," said John Whiteman, chief research scientist at Polar Bears International. Whiteman was not involved in the new study.

- The pace of ice sheet deterioration will determine whether the population of bears "might do better for a little while" or "end up in jeopardy," Whiteman told Axios.

- "These bears can really shed light on our understanding about the species," Laidre said, "And maybe how other similar areas in Greenland and Svalbard might be really critical to the persistence of polar bears as a species when we lose Arctic sea ice."

Read the entire story. |     | | | | | | 2. Catch up quick on COVID |  | | | Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios | | | | FDA advisers voted unanimously yesterday for emergency use authorizations of Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech COVID vaccines in children between 6 months and 5 years old, Jacqueline Howard at CNN reports. Pfizer's COVID-19 pill Paxlovid "didn't significantly reduce the risk of hospitalization or death in people with a standard risk of developing severe infections" in a study, per Axios' Adriel Bettelheim. Chronic COVID infections are being studied as possible sources of new variants, Ewen Callaway writes in Nature. |     | | | | | | 3. Survey: More representation could help close Latino STEM gap |  Reproduced from Pew Research Center; Chart: Axios Visuals Hispanics say the key to improving diversity in science hinges on seeing more Hispanic scientists, science students and science teachers, according to a Pew Research Center report published Tuesday. State of play: The survey of 3,700 Hispanic adults found about 30% of Latinos see scientists as unwelcoming to Latinos, which could hinder efforts to diversify the field, my colleague Astrid Galván and I write. The big picture: Latinos make up 17% of the U.S. workforce but only 8% of people working in science, technology, engineering or math, Pew found earlier. - The percentage of Latino college students earning a bachelor's degree in a STEM field is up from 8% in 2010 to 12% in 2018, according to the latest available data.

By the numbers: Only 26% of 1,821 Latinos surveyed said scientists as a professional group are very welcoming of Hispanics. And only 35% of them said Hispanic people have reached the highest levels of success in science, compared to 59% for medical doctors. - 81% of respondents said young Hispanic people would be more likely to pursue STEM degrees if they saw more examples of high-achievers in the field who are Hispanic.

What they're saying: Erika Tatiana Camacho, a professor of applied mathematics at Arizona State University, says educating parents about STEM fields and the jobs they offer could help drive more Latino students to the field. - Camacho is a program director at the National Science Foundation, which is supporting a slate of new programs at Hispanic-serving institutions (colleges that serve an at least 25% Hispanic full-time student population) that add a cultural perspective to how they teach STEM.

- Many times students are asked "to leave [their] identity at the door of the classroom ... as opposed to bring in who they are to the center point," she says.

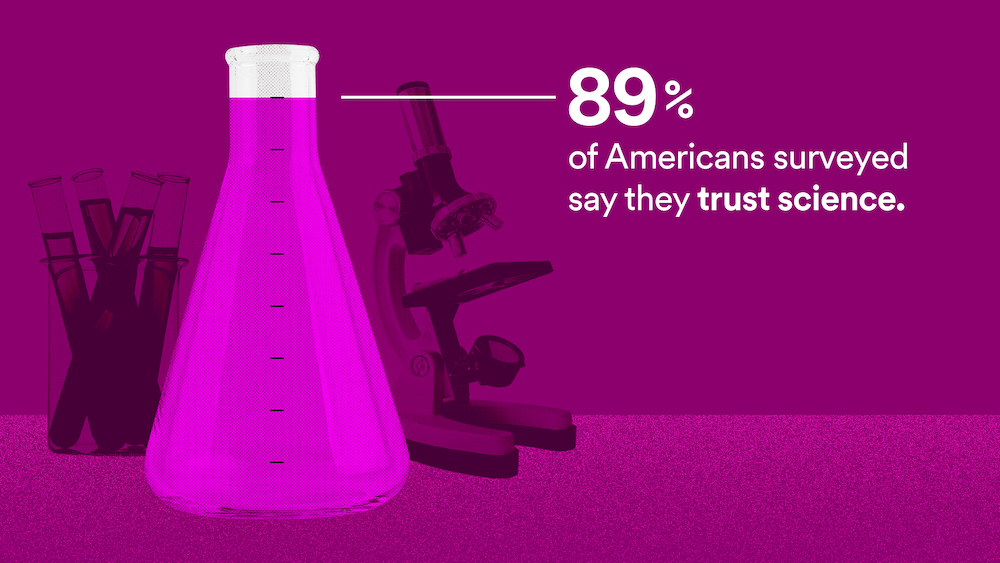

|     | | | | | | A message from 3M | | Trust in science is high, but misinformation poses a threat | | |  | | | | 3M is partnering with the world's largest digital journalism association to address the consequences of misinformation in media. Why now: 34% of Americans say they're skeptical of science and 47% believe science divides people with opposing views. Read the 3M 2022 State of Science Index. | | | | | | 4. Worthy of your time | | Ten years after the Higgs, physicists face the nightmare of finding nothing else (Adrian Cho — Science) Mystery of Black Death's origins solved, researchers say (Ian Sample — The Guardian) How the ocean inside the mantle affects the habitability of the Earth (Theo Nicitopoulos — Hakai) |     | | | | | | 5. Something wondrous |  | | | An uncontrolled landing. Video: Richard L. Essner Jr./ Southern Illinois University Edwardsville | | | | A teeny tiny frog has an inner ear canal so small it can't land on its feet, scientists report this week. The big picture: The evolution of jumping gave frogs — a diverse and large group of vertebrates — an edge. - But, "most of what's known about frog jumping is based on easily accessible frogs and toads," says Richard Essner Jr., a professor of biology at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville and a co-author of the study published this week in Science Advances.

- Extremely small species can offer insights into how and when jumping evolved.

Details: Pumpkin toadlets, which belong to the Brachycephalus genus, live in Brazil's Atlantic Forest and are about 0.4 inches long. - If they are "put on a dime, there is plenty of room to spare," Essner says.

- Pumpkin toadlets are part of a group of frogs with relatively advanced jumping skills, but after the tiny frogs launch, they cartwheel and backflip in the air before landing uncontrollably. (But seemingly unhurt.)

What they found: CT scans revealed the frogs' inner ear canals — which are part of the vestibular system that provides the brain with information about movement and balance — are very small. - So small that the fluid that sits in the ear canal and typically helps the body sense its position can't move — and the frog can't tell its orientation as it jumps and prepares for landing.

What's next: Essner says he wants to study the soft tissue in the canal and look at the jumping of other miniaturized frog species. |     | | | | | | A message from 3M | | The state of trust in science | | |  | | | | The 2022 State of Science Index found global trust in science is high and appreciation is stronger than in pre-pandemic times. Here's why: People recognize the relevance of science to their lives and are looking for science to provide solutions to major social issues. Get all the facts. | | | | Thanks to Andrew for contributing, Sam Baker for editing and Carolyn DiPaolo for copy editing. |  | It's called Smart Brevity®. Over 200 orgs use it — in a tool called Axios HQ — to drive productivity with clearer workplace communications. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters. If you're interested in advertising, learn more here.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1300, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment