| | | | | | | | | | | Axios Science | | By Alison Snyder ·Mar 31, 2022 | | Thanks for reading Axios Science. This week's edition is 1,500 words, about a 6-minute read. | | | | | | 1 big thing: Big data's promise for medicine |  | | | Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios | | | | The goal of reaching an era of individualized precision medicine will first require a closer look at the broader population, Axios' Eileen Drage O'Reilly writes. The big picture: Large clinical trials and massive databases of de-identified genetic and other health information — sometimes from generations of populations — are offering scientists and doctors data to decipher why certain individuals have a higher risk of disease or different responses to treatments. - Until the roles of genetics, ancestry, environment, diet, age and gender are better understood, precision medicine will remain an elusive goal.

- By running large clinical trials of treatments that incorporate people from all communities and backgrounds, there's a better chance of knowing if certain groups will respond differently.

- And by collecting and tracking genetic and other information from people from diverse backgrounds and circumstances, researchers — often using machine-learning or AI — can examine what happens to a particular group's health over longer periods of time.

What's happening: There are many institutions gathering this data, including... What's new: The COVID-19 pandemic led various groups to collectively create large-scale studies to seek safe and effective COVID treatments as rapidly as possible, such as the U.K.'s Recovery trial on more than 47,000 participants and the WHO's Solidarity Therapeutics Trial on 14,200 randomized hospitalized patients globally. Growing awareness of the problems caused by a lack of diversity in clinical trials and in most genetic databases has led to other changes. - The U.S. research program All of Us, which has more than 480,000 participants, recently released whole genome sequences from almost 100,000 U.S. participants, almost half of whom are from underrepresented groups.

- That All of Us data is expected to lead to discoveries that could reduce health disparities and help us "move away from a one-size-fits-all approach to treatment," says Karriem Watson, chief engagement officer of All of Us.

- Smaller public-private partnerships are also tackling the issue. For instance, Sema4, a patient-centered AI health care company, launched the REPRESENT trial to enroll 5,000 advanced-stage cancer patients from diverse populations in comprehensive genetic and genomic testing, says Sema4 chief medical officer and oncologist William Oh.

Reality check: Personalized medicine continues to face serious challenges and has sometimes resulted in deadly missed targets. But many hope accumulating data from large, more diverse trials will help alleviate those issues. Between the lines: Large cohort studies are one of the key "strategies to be able to understand the risk factors associated with cancer and with other diseases," says Marcia Cruz-Correa, physician-scientist at the University of Puerto Rico Comprehensive Cancer Center. - For example, the Framingham study found that high levels of cholesterol were a risk factor for coronary artery disease — "and now we don't even think twice about checking cholesterol levels as a standard of care," says Cruz-Correa.

- "We've been basically missing the boat on a very large proportion of patients who are underrepresented in clinical cancer treatment and research," Oh says.

The bottom line: These massive datasets are expected to help tease out the biological and socioeconomic factors of disease, Oh says. "They're all tied together." |     | | | | | | 2. Catch up quick on COVID |  Data: Our World in Data; Chart: Jared Whalen/Axios "COVID vaccine supply struggles are easing, but in 44 counties — most of them in Africa — less than 20% of the population is fully vaccinated. In 19, the rate is under 10%," Axios' Dave Lawler reports. "After plummeting for several weeks, the number of new COVID cases in the U.S. has largely leveled off," Axios' Tina Reed and Kavya Beheraj write. Just over half of all new COVID cases in the U.S are due to the Omicron subvariant BA.2, per Axios' Shawna Chen. The earlier COVID antibody treatments are given, the more effective they are, Ewen Callaway reports for Nature. |     | | | | | | 3. China makes genetic data a national resource |  | | | Illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios | | | | The Chinese government has identified genetic data as a national strategic resource and is strengthening state control over the country's gene banks and other repositories of genetic information, Axios' Bethany Allen-Ebrahimian reports. Why it matters: The collection and use of genetic information are fraught with ethical concerns, including consent and privacy, exploitation of marginalized groups, and a growing transnational trend toward genetic surveillance. - "The Chinese authorities are making a real effort to protect the genetic information of Chinese citizens from non-state actors," Yves Moreau, a geneticist at the University of Leuven in Belgium, tells Axios, while carving out a "huge exception for the state."

Driving the news: Newly released draft guidelines prohibit the genetic information of Chinese nationals from being sent abroad and mandate the cataloging of human genetic databases, including data at academic institutions, to be carried out every five years. - The guidelines offer details for implementing a brief set of regulations issued by China's State Council in 2019 for governing the management of genetic information after a major scandal in which a Chinese scientist performed gene-editing on human embryos.

- They specifically designate the science and technology bureau of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps — a sprawling paramilitary organization sanctioned by the U.S. government for complicity in operating mass internment camps and forced labor in Xinjiang — as responsible for managing the survey in the regions it administers.

The big picture: Other countries, including the U.K. and the U.S., have created large databases of genetic and health information from hundreds of thousands of participants, but China's new rules suggest a new level of governmental control on genetic information. - "It's natural for any state to consider genetic information something strategic. But this is going very far, saying that the state will be the central judge of how we manage this kind of information, both internationally and nationally," Moreau said.

- The prohibition on transmitting Chinese genetic data abroad and protecting it from abuse by private actors, while ensuring the government has total access and control, resembles the principle enshrined in China's new data privacy law.

- "It comes from a philosophy that seems to be quite strong right now in China as viewing genetic resources as a strategic resource. Like 'data is the new oil' — genetic data is one of those things," Moreau said.

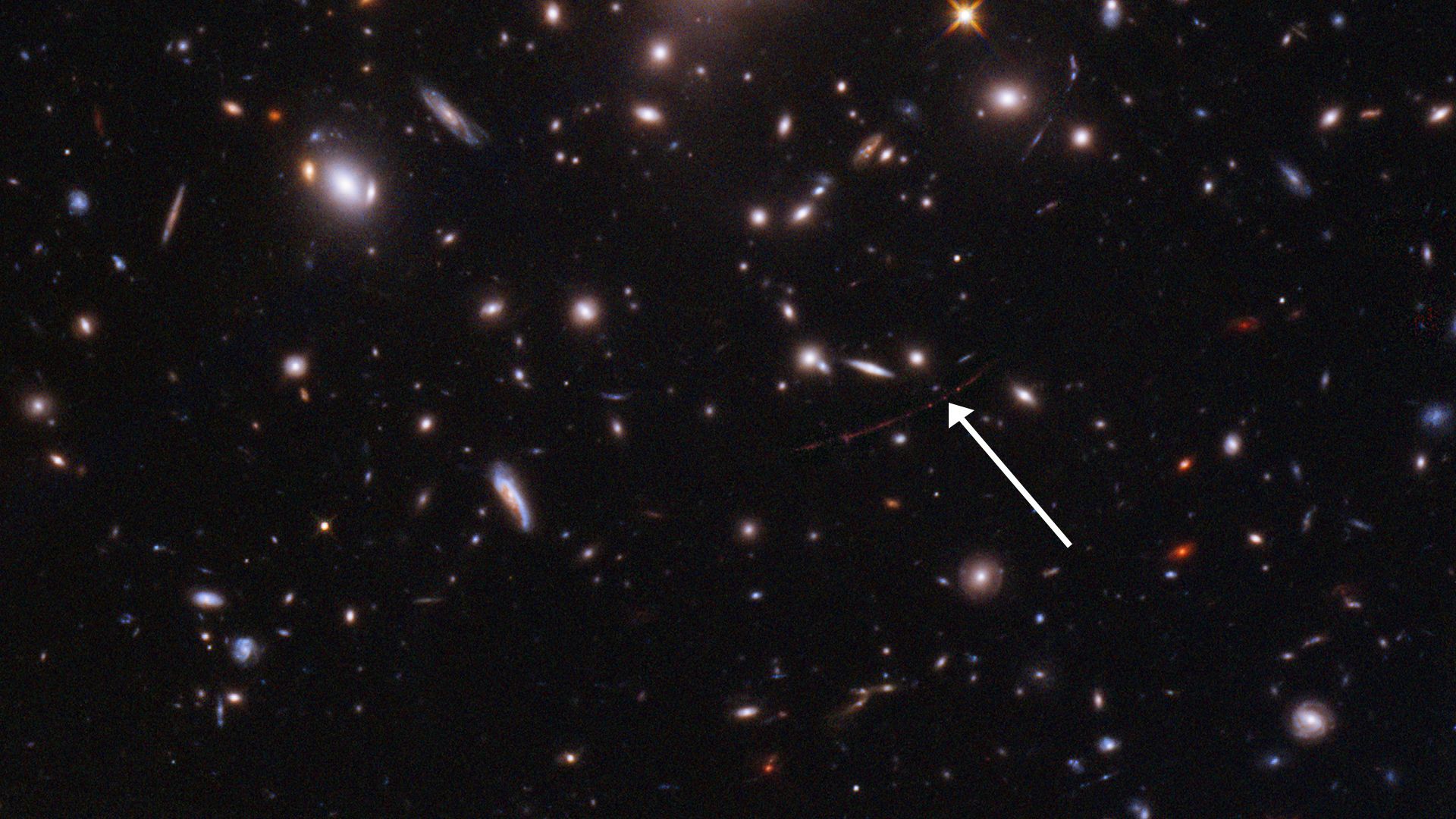

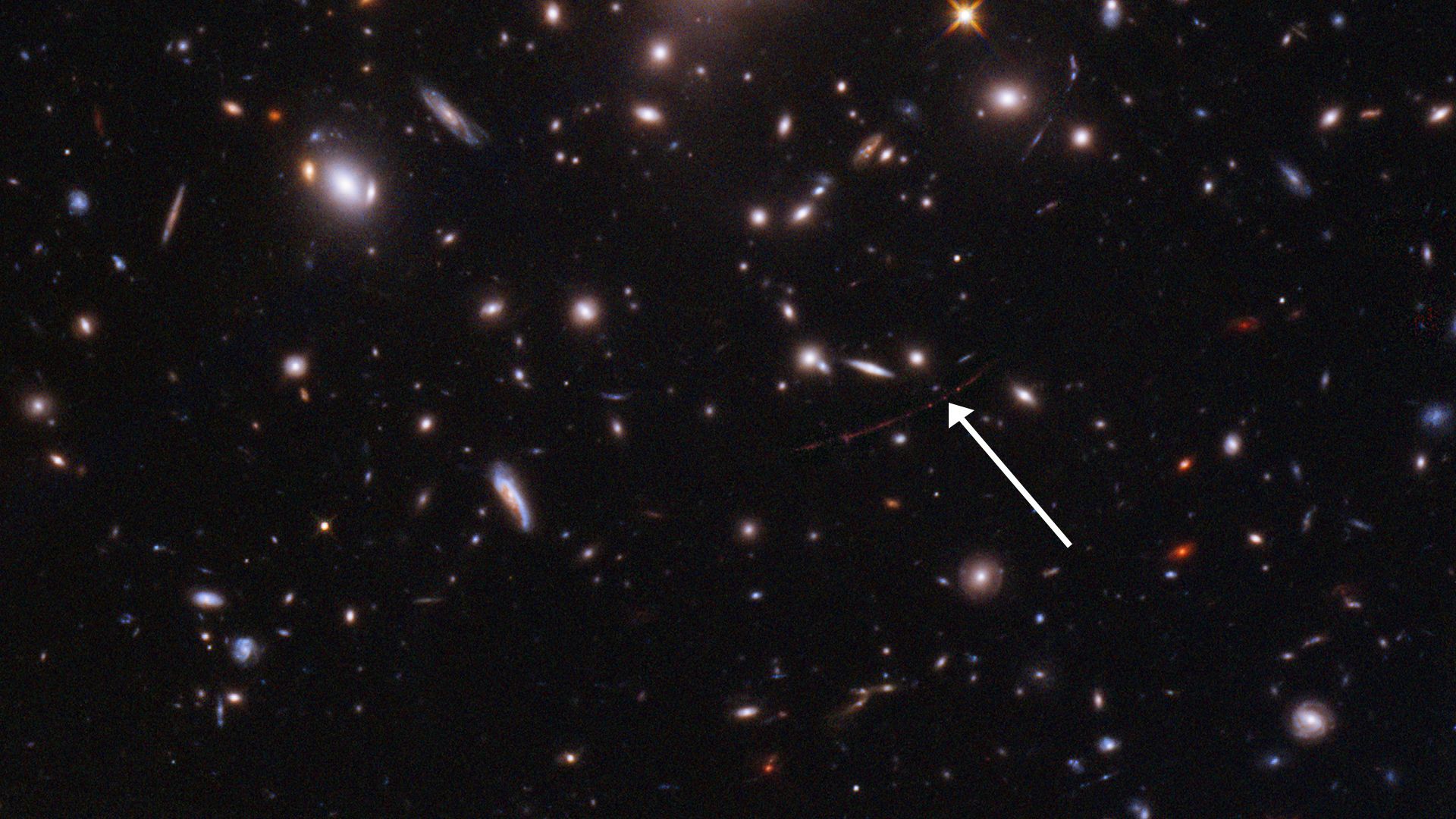

Read more. |     | | | | | | A message from Axios | | Get the top stories shaping our world in your inbox | | |  | | | | Take a tour of the most important stories around the globe with Axios World. Delivered weekly to your inbox by world editor Dave Lawler. Subscribe for free | | | | | | 4. Worthy of your time | | How a basement hideaway at UC Berkeley nurtured a generation of blind innovators (Isabella Cueto — STAT) Keep getting lost? Maybe you grew up on the grid (Benjamin Mueller — NYT) Under the sea, a hidden climate variable (Matt Simon — Undark) The long goodbye to Saturn's rings (Marina Koren — The Atlantic) |     | | | | | | 5. Something wondrous |  | | | The star Earendel (indicated by the arrow) is positioned along a ripple in spacetime. Image: NASA, ESA, JHU, STScI | | | | The Hubble Space Telescope detected light from the most distant individual star ever seen to date, Axios' Jacob Knutson writes. Why it matters: Light from the star, which existed within the first billion years after the Big Bang, took 12.9 billion years to reach Earth, NASA announced yesterday. - The previous record of the farthest star ever seen took 9 billion years to reach Earth, and it was detected by Hubble in 2018.

The big picture: Hubble detected the star — which researchers named "Earendel," meaning "morning star" in Old English — through a natural gravitational lens caused by clusters of galaxies that magnifies light from distant galaxies behind this gravitational field. - Researchers estimate Earendel is at least 50 times the mass of the sun and millions of times as bright, rivaling the most massive stars known.

What they're saying: "We almost didn't believe it at first, it was so much farther than the previous most-distant, highest redshift star," Brian Welch, an astronomer at Johns Hopkins University and the lead author of the paper describing the find in the journal Nature, said in a statement. - "Normally at these distances, entire galaxies look like small smudges, with the light from millions of stars blending together."

- "Earendel existed so long ago that it may not have had all the same raw materials as the stars around us today," he added. "Studying Earendel will be a window into an era of the universe that we are unfamiliar with, but that led to everything we do know."

What's next: Welch and other researchers plan to view Earendel with NASA's newly launched James Webb Space Telescope, which is significantly more powerful than Hubble. - "With Webb we expect to confirm Earendel is indeed a star, as well as measure its brightness and temperature," said Dan Coe, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute and co-author of the paper.

- Coe said he expects Webb will be able to help determine the elements that make up Earendel. The star was formed before heavy elements were largely present in the universe, and it could be a rare massive low-metal star largely made up of primordial hydrogen and helium.

|     | | | | | | A message from Axios | | Get the top stories shaping our world in your inbox | | |  | | | | Take a tour of the most important stories around the globe with Axios World. Delivered weekly to your inbox by world editor Dave Lawler. Subscribe for free | | | | Big thanks to Carolyn DiPaolo for copy editing this week's edition. |  | It's called Smart Brevity®. Over 200 orgs use it — in a tool called Axios HQ — to drive productivity with clearer workplace communications. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters. If you're interested in advertising, learn more here.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1300, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment