| | | | | | | Presented By Yieldstreet | | | | Axios Markets | | By Sam Ro ·Aug 03, 2021 | | Today's newsletter is 1,281 words, 5 minutes. 💬 of the day: "Supply chains are slowly, very slowly filling up. Like a water hose, starting upstream and slowly flowing downstream." - a respondent to the July ISM manufacturing survey | | | | | | 1 big thing: Why companies aren't paying more |  | | | Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios | | | | If companies raised pay high enough, then maybe they wouldn't complain about labor shortages that have forced them to forgo sales. But there seems to be a limit to how much a company is willing to pay, despite what seems like a clear opportunity to maximize the top line. Why it matters: Companies have been scrambling to staff up amid a rapid economic recovery. Employers across industries have been raising wages in their efforts to be competitive. What they're saying: Increasing wages is essentially a wager that today's demand will persist and justify higher labor costs in the years to come. And companies don't want to be in a position to have to reverse that decision. - "Companies are hesitant to lower wages," ADP chief economist Nela Richardson explains to Axios. "What generally happens is that companies don't decrease pay during a recession, but they are hesitant to increase pay after that recession ends."

- Much of the labor shortages are occurring in industries where profit margins are already thin, Richardson notes. These include the leisure and hospitality industry, where the risk of profits turning into losses is already high.

And employers can't offer higher pay to just the new people. - "Especially in thin margin businesses, if you pay to attract newer workers, you also have to pay to keep and retain your tenured staff," Richardson says.

Zoom out: There's a wide array of logistical reasons a company may have job openings that it's putting off filling, Wells Fargo economist Shannon Seery tells Axios. - "Perhaps severe supply constraints of inputs mean firms may not be paying more aggressively to recruit because they lack the inputs to produce even if they had the labor," Seery says.

The bottom line: While there appears to be a disconnect between companies complaining about labor shortages and what they're doing about pay, the bias in the labor market continues to favor workers and their wages. - "Wages are on the rise across a number of industries, making the hiring environment all the more competitive and leaving job seekers with the upper hand to be 'picky' in terms of job prospects," Seery says. "Firms will either pay up for inputs and labor today or their competitors will."

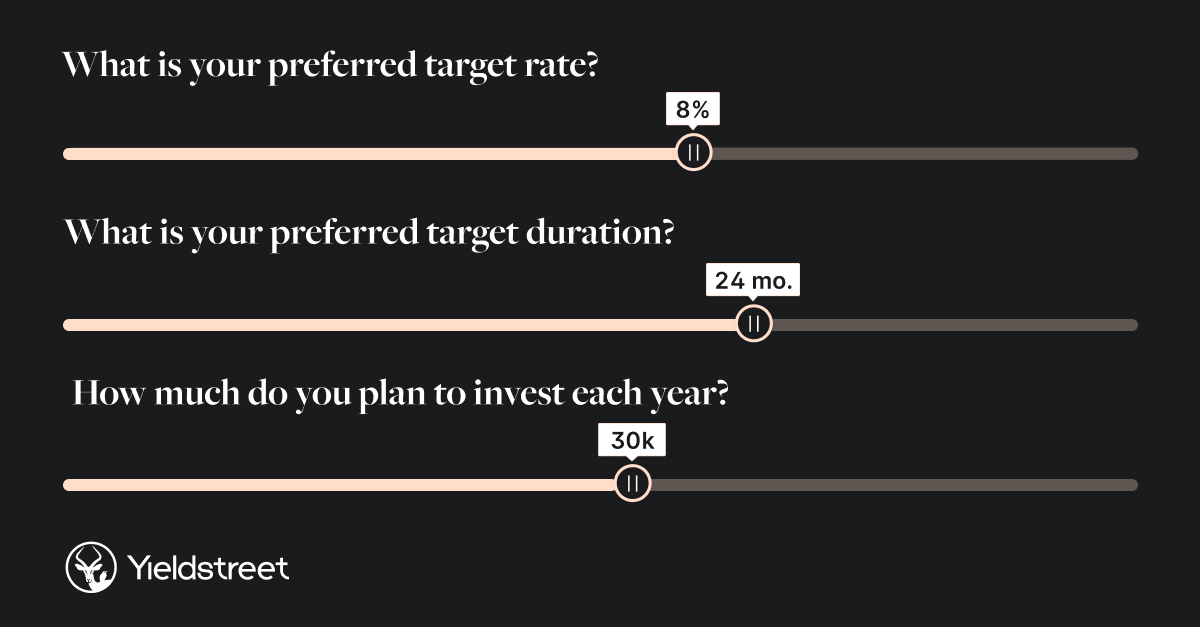

|     | | | | | | 2. Catch up quick | | Chinese state media published and then deleted an article describing online gaming as "spiritual opium," which sent shares of Tencent tumbling. (Reuters) Sanofi is buying biotech company Translate Bio for $3.2 billion. (Bloomberg) |     | | | | | | 3. Buy now, pay later is coming to a retailer near you |  Data: FIS Global; Chart: Sara Wise/Axios Buy now, pay later (BNPL) is one of the hottest parts of fintech, built on the idea that a simple pay-in-installments plan doesn't really feel like a loan — especially when it comes with 0% interest. Now that idea has driven Square to acquire Australia-based BNPL giant Afterpay for about $32 billion in stock, based on where its share price closed on Monday, Axios chief financial correspondent Felix Salmon writes. Why it matters: Consumers unwilling or unable to open traditional credit cards can still be persuaded to borrow money if the marketing message is attractive enough. - Market leader Klarna recently bought an influencer marketing company and has used Snoop Dogg and A$AP Rocky as pitchmen. Its chief marketing officer told Reuters last week that introducing a new way to borrow money should be a bit like "when Nike drops a new sneaker."

- Square has already bought Tidal, Jay-Z's struggling music-streaming service, and has seen the growth of its Cash App turbocharged by hip-hop stars and other social media influencers.

What they're saying: "What sets BNPL apart from traditional shopping is how it repackages debt into a form of self-care," writes the Guardian's Kitty Drake. - Not mentioned in the marketing campaigns: The way in which racking up BNPL obligations can result in consumers being unable to obtain a mortgage, per an investigation by Refinery29.

How it works: Europeans, who have traditionally eschewed credit cards, still want to buy items online even when they don't have the full amount available in their bank accounts. BNPL now accounts for 7.4% of European e-commerce transactions, per FIS Global. - Investors are assuming that younger U.S. consumers will also adopt BNPL, although the U.S. market share is still very low, and much of it is concentrated in the relatively unique relationship that Affirm has with Peloton.

- Markets without broad credit card adoption are in many ways even more attractive. Indonesia's market leader Kredivo, for instance, is going public at a $2.5 billion valuation.

What's next: Soon, whenever you buy a big-ticket item at a store with a Square terminal, you'll be able to opt to pay for it in installments. Taken directly out of your Cash App account, of course. |     | | | | | | A message from Yieldstreet | | How to diversify your portfolio like the ultra-wealthy | | |  | | | | You can diversify your investment portfolio while generating passive income with Yieldstreet. Here's how: The platform lets savvy investors go beyond crypto and the stock market, giving them access to alternative investments such as art, real estate and more. Put your money to work. | | | | | | 4. Markets could be just fine when tapering comes |  | | | Photo: Daniel Acker/Bloomberg via Getty | | | | Experts warn that the Federal Reserve's plan to eventually taper its quantitative easing program could bring volatility to the markets. But the volatility could prove limited. Why it matters: QE is an emergency monetary policy tool that involves large-scale purchases of Treasury and mortgage-backed securities in an effort to keep the bond markets liquid and well-functioning during times of stress. Flashback: In the wake of the global financial crisis, the Federal Reserve employed QE for years before saying in May 2013 that it could begin tapering later that year. - The discussion was received poorly by the markets, which saw stocks and bonds tumble hand-in-hand.

What they're saying: "Market participants may view the Fed's initial announcement about its intentions for tapering as one signal about the timeline for interest rate hikes," Goldman Sachs U.S. equity strategist David Kostin wrote. - In other words, the announcement, which is expected to come later this year, could be seen as a signal for sooner-than-expected rate hikes, which currently aren't expected to happen until 2023.

- The 2013 "taper tantrum" episode was driven by "fears about the premature removal of monetary support and the potential for imminent rate hikes," Kostin says.

Yes, but: "Ultimately, the [2013] selloff proved temporary; the S&P 500 returned 32% in 2013," Kostin notes. State of play: Last week, the Federal Reserve signaled that it could be months before it communicated plans to taper QE. - In a speech given on Monday, Fed governor Lael Brainard sent similar signals, saying she wants to have economic data "in hand for September" before deciding what's next for policy.

The bottom line: The 2013 taper tantrum could very well be renamed the "taper triumph" considering how quickly the markets bounced back and then some. |     | | |  | | | | If you like this newsletter, your friends may, too! Refer your friends and get free Axios swag when they sign up. | | | | | | | | 5. The outlook for business travel isn't great |  | | | Illustration: Annelise Capossela/Axios | | | | Even if virus fears become a thing of the past, long-term cost savings and corporate commitments to reduce carbon emissions mean business travel won't return to pre-pandemic levels any time soon, Axios' Erica Pandey writes. Why it matters: Business travel is a massive part of the global economy with trillions of dollars and millions of jobs at airlines, hotels and travel agencies hinging on its return. - While business travelers only make up around 10% of airline passengers across the major global carriers, they account for 55%–75% of revenue because they're typically the ones who spend big on last-minute tickets or book premium seats, the New York Times' Jane Levere reports.

By the numbers: 76% say they're turning more internal meetings that would require flying into online ones. - 58% say they'll do fewer business trips overall.

- 55% say they'll specifically look at cutting back on international corporate travel.

What they're saying: "Companies used to send maybe eight people to close a deal. Now they'll send two people, and the rest will be on Zoom," says Charlie Leocha, president of Travelers United, a passenger-advocacy organization. Keep reading |     | | | | | | A message from Yieldstreet | | Now you can invest like the ultra-wealthy | | |  | | | | Yieldstreet, an alternative investment platform, has returned over $1 billion in principal and interest to investors to date. More info: Their deals typically have short durations — three months to five years — and target annual yields of 3-15%. Join 300,000+ members today. | | |  | | It'll help you deliver employee communications more effectively. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters. If you're interested in advertising, learn more here.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1300, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment