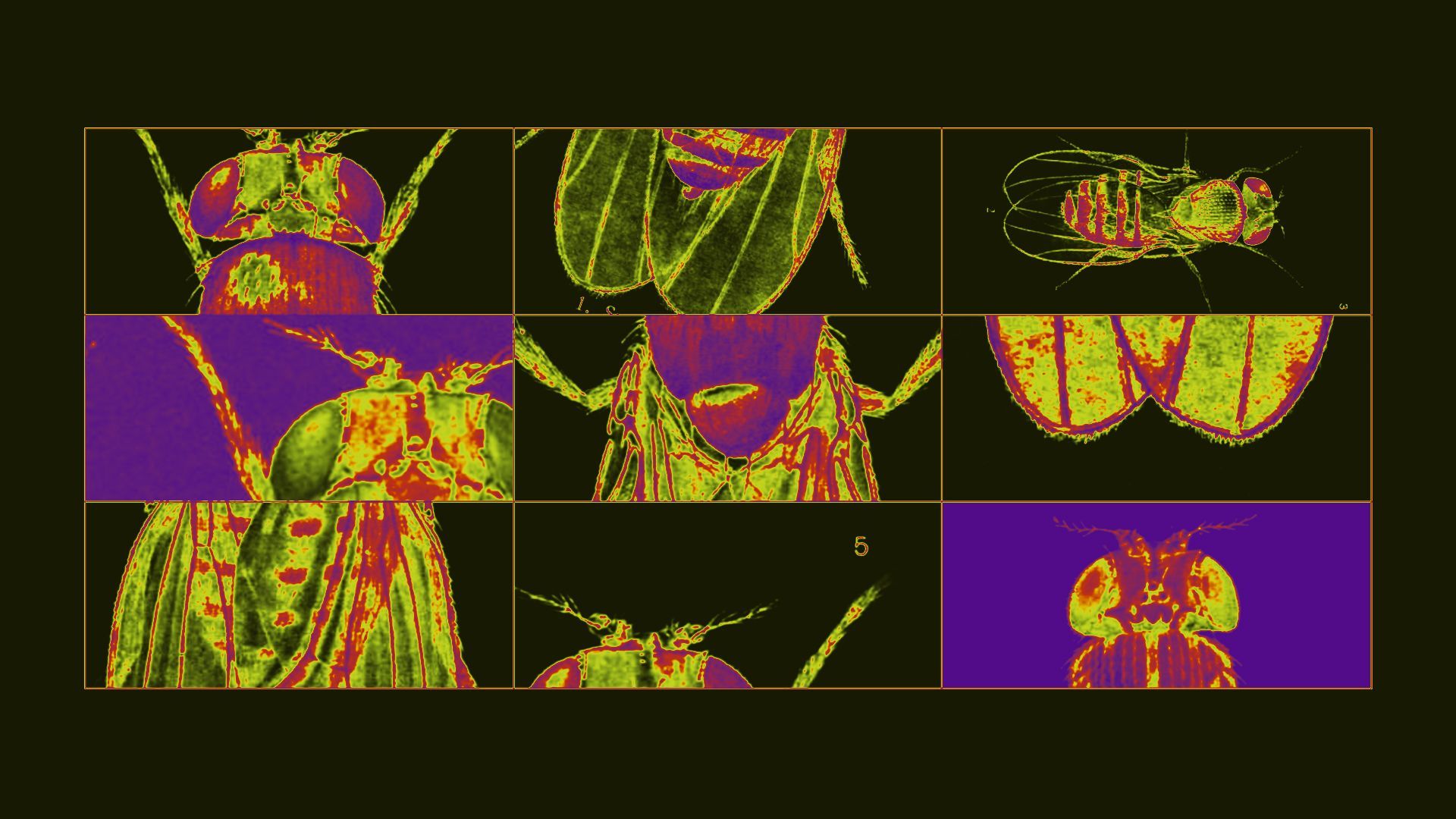

| | | | | | | Presented By Babbel | | | | Axios Science | | By Alison Snyder · Mar 09, 2023 | | Thanks for reading Axios Science. This week's newsletter is 1,709 words, about a 6-minute read. 💥 Axios is hosting our second annual What's Next Summit on March 29 in Washington, D.C., spotlighting the innovations, trends and people that are breaking boundaries and shaping our world. Register for the event livestream here. | | | | | | 1 big thing: Clues from a complex bug brain map |  | | | Photo Illustration: Natalie Peeples/Axios. Photos: Biodiversity Heritage Library | | | | A new map of a maggot's brain offers details about the wiring of neurons involved in learning — and could offer insights for powering AI in the same task. Why it matters: The fly brain diagram will allow scientists to probe how the brain's hardware shapes behavior. It could also reveal circuits that evolved over hundreds of millions of years — and could suggest ways to process information with less energy, a problem plaguing AI. - "Both natural and artificial intelligence is learned so understanding learning fundamentally is agnostic" to whether it is neurons or silicon, says Joshua Vogelstein, an assistant professor of biomedical engineering at Johns Hopkins University.

- "What is it to say it is learning? And what are the mechanisms of learning? Those principles will be helpful to better understand what is happening in ourselves and to build better tools to serve us."

What's new: A team of researchers, including Vogelstein, today published a complete wiring diagram — or connectome — of a fruit fly larva's brain. It's the largest and most complex complete nervous system mapped to date, and the culmination of more than a decade of work. - The scientists created images of a six-hour-old female Drosophila melanogaster's brain by using electron microscopy to study 4,841 brain slices, each about 50 nanometers thick, and then reconstructed the connections between neurons.

What they found: There are 3,016 neurons and 548,000 synapses, or connections, in the fruit fly's brain, according to the study published in the journal Science. - The scientists found 93 distinct types of neurons and determined their connections, hubs in the neuron networks and different types of circuits.

- They found many of the dopaminergic neurons involved in learning had recurrent connections, that send signals forward and backward with a partner.

- Those pathways of neurons in the fly larva brain "resembled prominent characteristics of state-of-the-art machine learning networks."

Yes, but: The researchers mapped the brain of one fruit fly larva. - "It is just one maggot. We could have gotten a weird one," Vogelstein says. "It's unlikely because they are clones but it is certainly possible and if so, we might learn a lot about one and a little in general."

- Fruit fly larvae have complex behaviors like moving toward food but unlike adults, they don't yet fly and have only limited vision, says Stanley Heinze of Lund University in Sweden, who studies insect neuroscience and was not involved in the new research. "But the overall principles are the same in the end, and the insights provide the roadmap or mental scaffold for how to interpret more complex connectomes."

- A separate team is trying to map the brain of an adult fruit fly.

- The diagram is also missing information: the dynamics of how a connectome changes from one moment to the next; whether a neuron is moving information along in the network or inhibiting it; and the types of chemical signals, called neurotransmitters and neuromodulators, at work.

Scientists have debated how much can be gleaned about an animal's behavior from a connectome. - It is "unlikely to be sufficient" for understanding learning and intelligence because it is missing "lots of details of how information is flowing but it is likely to be required to understand the mechanism," says Vogelstein, who is in the camp that the architecture of the brain is important for understanding behavior.

- The connectome is a reference for people to test hypotheses about behavior and development, and the tools they developed to create it can be applied to other connectomes, he says.

- Researchers are trying to map the human brain as well.

What to watch: The brain architecture of insects could hold clues about how to process information with less energy, a potential solution to a problem for today's AI and computation. - Insects "solve these problems in an efficient way with much fewer neurons," Heinze says.

- The paper "gives us the hardware ... that resulted from 500 million years of evolution and was made very efficient."

|     | | | | | | 2. Wildfire smoke's ozone destruction |  | | | Firefighters watching a large bushfire burning near Bargo, Australia, in December 2019. Photo: Peter Parks/AFP via Getty Images | | | | The smoke released by major wildfires likely contributes to the destruction of ozone, the vital atmospheric shield that protects the planet by absorbing most of the sun's harmful ultraviolet radiation, according to a new study published yesterday in Nature. Why it matters: Wildfires are projected to become more frequent and intense over the coming decades due to global warming and land-use change, Axios' Jacob Knutson writes. - A UN-backed panel of scientists estimated that the recovery of Earth's ozone layer was back on track. But increased levels of wildfire smoke in the atmosphere could delay that recovery, the researchers behind the new study found.

Details: The researchers studied the aerosol from major fires in Australia during the austral summer of 2019–2020 to try to better understand the chemical mechanism behind wildfire smoke contributing to ozone degradation. - During that time, which was later dubbed the "black summer," several devastating fires scorched about 59 million acres, killed at least 33 people and killed, wounded or displaced millions of animals.

- Blazes during that fire season also produced massive pyrocumulonimbus cloud towers that injected around 0.9 teragrams (nearly 1 trillion grams) of wildfire smoke into the lower stratosphere.

How it works: The researchers hypothesized that oxidized organics, particularly organic acids, within smoke released by wildfires increase the solubility of hydrochloric acid (HCl) in the lower stratosphere. - As HCl dissolves into smoke particles under stratospheric conditions, reactive chlorine species are activated and contribute to the destruction of ozone molecules, the researchers proposed.

- Just one reactive chlorine atom in the stratosphere can destroy tens of thousands of ozone molecules before it reacts with another gas and finally stabilizes. After reacting with chlorine atoms, ozone breaks down into normal oxygen, which does not absorb harmful ultraviolet radiation from the Sun.

- The researchers tested their hypothesis by comparing simulations of the proposed chemical process with atmospheric observations of the Southern Hemisphere mid-latitudes following the 2019–2020 Australian wildfires.

- The simulations produced inconsistencies in the levels of chlorine species and ozone that were "in remarkable agreement" with the observations, which supported their hypothesis.

Go deeper. |     | | | | | | 3. Our winters are warming faster than our summers |  Reproduced from Climate Central. Map: Axios Visuals Average winter temperatures across the United States have increased by 3.2°F since 1970, according to an analysis from Climate Central, a nonpartisan research and communications group, Axios' Andrew Freedman writes. Why it matters: Warm winters can exacerbate drought (because there's less snowmelt in the spring), wreak havoc on crops and gardens, and spell disaster for towns built around skiing, snowboarding, and similar pursuits. The big picture: Winter is the fastest-warming season for much of the continental U.S. - About 80% of the country now has at least seven more winter days with above-normal temperatures compared to 1970, per Climate Central.

- Seasonal snowfall is declining in many cities — although heavy snowstorms can still happen when temperatures are cold enough.

- In fact, precipitation extremes are happening more frequently and getting more intense, which can lead to feast or famine snowfall.

Driving the news: Not only are winters warming overall, but cold snaps are becoming less severe and shorter in duration, the latest research shows. - That's partly because the Arctic is warming at three to four times the rate of the rest of the world.

- In other words, our global refrigerator is warming up, making it harder to get record-breaking cold for days on end when weather patterns transport Arctic air southward.

Zoom out: This past winter was especially mild across areas east of the Mississippi River. But across the West, it was colder than average. This is reflected in the balance of daily record highs to daily record lows. - Preliminary NOAA data processed by Climate Central shows there were 4,857 daily record highs set or tied in the lower 48 states this past winter, and 4,421 daily record lows set or tied.

- A combination of La Niña, a strong polar vortex, and a stubborn area of high pressure in the far western Atlantic Ocean favored a weather pattern that kept the East Coast on the warm side of winter storms, delivering snow across the Great Lakes northward into Ontario and Quebec.

- This was the 17th-warmest winter on record across the U.S., as colder conditions in the West balanced out milder temperatures in the East.

The bottom line: Over the coming years, most of us can expect to feel climate change's effects more acutely during the winter months. |     | | | | | | A message from Babbel | | Speak a new language in 3 weeks | | |  | | | | If you're planning a summer trip, now is the time to start learning the local language. With just 10 minutes a day, you could be speaking a new language by summer thanks to Babbel, a premium language learning platform that can tailor to topics that interest you. Start now and get 55% off your subscription. | | | | | | 4. Worthy of your time | | The women of Venus (Kavya Beheraj — Axios) Can a 1975 bioweapons ban handle today's biothreats? (Matt Field — Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists) A new superconductor claim faces scrutiny (Emily Conover and James R. Riordon — Science News) The false promise of ChatGPT (Noam Chomsky, Ian Roberts and Jeffrey Watumull — NYT) The mice with two dads (Heidi Ledford and Max Kozlov — Nature) |     | | | | | | 5. Something wondrous |  | | | Photo: Creative Touch Imaging Ltd./NurPhoto via Getty Images | | | | Bumblebees can learn from one another to solve a puzzle — suggesting the insects may have some form of culture, according to a new study. The big picture: Birds, chimpanzees, whales and other animals are believed to transmit knowledge to one another and from generation to generation, which is considered by many to be the essence of culture. The new study was published this week in PLOS Biology. What they did: Scientists at Queen Mary University of London trained bumblebees to open a puzzle box containing a sugar solution by rotating a lid. - The lid rotated clockwise when the insect pushed a red tab and counter-clockwise when it pushed a blue one.

- Some bees were trained to open the box by pushing the red tab and others by pushing the blue tab.

- The trained bees were then placed in separate colonies.

What they found: The bees in the colonies tended to push the color tab that their "demonstrator" pushed. - And they continued to do it even when they figured out the other way worked as well.

- Bees in control colonies without demonstrators didn't consistently push the tabs.

What's next: The researchers are planning to study the behavior in bees that live in colonies for years to see whether the knowledge is passed from one generation to the next, the study's lead author Alice Bridges told NPR. - "Maybe [culture] doesn't require very, very complex cognitive mechanisms," she said. "Maybe it's not some pinnacle of cognition that only a few species have. Maybe it's actually very widespread."

|     | | | | | | A message from Babbel | | Spring forward and kickstart your language learning | | |  | | | | The challenge: Some language learning apps rely on AI and teach random phrases, creating an ineffective process for learners. The solution: With Babbel, you can learn a new language in just 3 weeks with lessons created by real language experts. Get up to 55% off your subscription for a limited time. | | | | Thanks to editor Laurin-Whitney Gottbrath, visual journalist Natalie Peeples and copy editor Carolyn DiPaolo. |  | | Are you a fan of this email format? Your essential communications — to staff, clients and other stakeholders — can have the same style. Axios HQ, a powerful platform, will help you do it. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

To stop receiving this newsletter, unsubscribe or manage your email preferences. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment