| | | | | | | Presented By PwC | | | | Axios Future | | By Bryan Walsh ·Apr 07, 2021 | | Welcome to Axios Future, which is ready for another vacation after returning from a vacation last week with a toddler. Today's Smart Brevity count: 1,905 words or about 7 minutes | | | | | | 1 big thing: Americans are leaving organized religion |  | | | Illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios | | | | New surveys show membership in communities of worship has declined sharply in recent years, with less than 50% of Americans belonging to a church, synagogue or mosque. Why it matters: The accelerating trend toward a more secular America represents a fundamental change in the national character, one that will have major ramifications for politics and even social cohesion. By the numbers: A Gallup poll released last week found just 47% of Americans reported belonging to a house of worship, down from 50% in 2018 and 70% as recently as 1999. - The shift away from organized religion is a 21st-century phenomenon. U.S. religious membership was 73% when Gallup first measured it in 1937, and it stayed above 70% for the next six decades.

Context: The decline in membership is primarily driven by a sharp rise in the "nones" — Americans who express no religious preference. - The percentage of Americans who do not identify with any religion rose from 8% between 1998 and 2000 to 21% over the past three years, while the percentage of nones who do not belong to a house of worship has risen as well.

The big picture: The story of a more secular America is chiefly — though not entirely — one of generational change. - Membership in houses of worship correlates with age, with the oldest Americans much more likely to be church members than younger adults.

- But while church membership is lower among younger generations, the drop-off is particularly stark among millennials and Gen Z, who are about 30 percentage points lower than Americans born before 1946, compared to 8 points and 16 points, respectively, for baby boomers and Gen X.

Details: Whatever their religious practices, Americans are increasingly rejecting many of the moral precepts found in most major religions. - A 2017 Gallup poll found a significant majority of Americans believe practices like birth control, divorce, extramarital sex, and gay and lesbian relations are all morally acceptable.

The catch: Just because conventional religious practice is on the decline doesn't mean Americans will have no need to fill what journalist Murtaza Hussain calls the country's "God-shaped hole." - While the earlier phases of the civil rights movement were built on the strength of the Black church, today, many young people are flocking to campaigns like Black Lives Matter that aren't religious in nature, but often adopt the language of religion, spirituality and justice.

- "Political debates over what America is supposed to mean have taken on the character of theological disputations," Shadi Hamid, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, wrote in a recent Atlantic essay. "This is what religion without religion looks like."

What's next: As religion decreasingly becomes something Americans practice, it may instead become another identity, subsumed into the ongoing culture wars. The bottom line: The U.S. remains an unusually religious country, with more than 7 in 10 Americans still affiliating with some organized religion, according to the Gallup poll. - But conventional religion's power is on the wane, and it might take a miracle for that to change.

Read the whole story |     | | | | | | 2. Health care leads the way for top private AI firms |  | | | Illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios | | | | A new list of the top 100 private AI companies shows that health is driving investment in the industry. Why it matters: COVID-19 has shown the power and potential of AI applications for health, and the growth of the field will continue long after the pandemic has finally ended. What's happening: This morning, the business research firm CB Insights released its annual AI 100 ranking of the most promising private companies working in artificial intelligence. - The list includes companies headquartered in 12 countries and nearly 20 different industries.

- The firms on the list have raised more than $11.7 billion in equity funding collectively since 2010, and 12 companies have a valuation over $1 billion.

What they're saying: "The list is a testament to not just the breadth of AI's impact but also the depth of automation within industries," says Deepashri Varadharajan, lead analyst for emerging tech at CB Insights. Details: AI companies focused on health care claimed the most spots on the list with eight, including some working on surgical technology, clinical trials and even dental insurance. - Health care AI startups enjoyed record funding in the third quarter of 2020, with 122 deals adding up to more than $2 billion.

- "While health care has always been one of the top categories in the AI 100, the pandemic certainly accelerated AI's adoption in the space," says Varadharajan.

The bottom line: One of the biggest takeaways of the AI 100 ranking is the way artificial intelligence has moved from the digital realm into the physical world — and there's nothing more physical than our health. Go deeper: Coronavirus accelerates AI in health care |     | | | | | | 3. Using "eyes in the sky" and AI to remotely rate insurance risks |  | | | Illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios | | | | A startup is employing machine learning to process aerial imagery and remotely analyze insurance risks to properties around the country. Why it matters: The combination of AI and aerial imagery from satellites and even stratospheric balloons can help insurers quickly judge property risks without an in-person visit, saving money and time. How it works: Arturo's AI model can identify potentially risky characteristics of a property — like roof tiles in need of repair or a pool that lacks a fence — and estimate the likelihood of an insurable accident in the future. - "We create high-fidelity information about the property in seconds for the insurers today, and likely lenders tomorrow, to understand what's actually there," says John-Isaac Clark, Arturo's CEO.

Background: Arturo's business model is a combination of two major technological trends: the ever-increasing growth of aerial imagery that can capture detailed pictures of the ground and the power of machine learning. - Before he became the CEO of Arturo, Clark was head of product at DigitalGlobe, a major commercial vendor of space imagery and geospatial content.

- "There's been a fundamental change in how we understand location as consumers," says Clark. "Whether it comes from space, from satellites, from airplanes, this imagery created for us a way to understand where things were and where we were going."

The big picture: Insurance might seem like the blandest of businesses, but since its origins hundreds of years ago, the field has focused on using available data to try to predict the future — which happens to be precisely what machine learning is good at. - A recent report from Porch Research found "InsurTech" companies like Arturo raised $5.4 billion in venture funding last year.

- As both the sources of data — Arturo recently partnered with Urban Sky to tap that company's cost-effective "Microballoon" imagery — and the computational power of AI systems grow, so will the InsurTech field.

The catch: Given that insurance essentially exists as a shared hedge against uncertainty, the better insurance companies get at predicting the future, the harder it might be for some properties or people with higher risk profiles to get protection. |     | | | | | | A message from PwC | | Three trends that are transforming the post-pandemic workforce | | |  | | | | A recent PwC Workforce Pulse Survey found that: - Workers are on the move, with 22% planning to move over 50 miles from their job.

- Gen Z and millennials see a future where remote work is a given.

- Many employees now view soft skills as critical to their success.

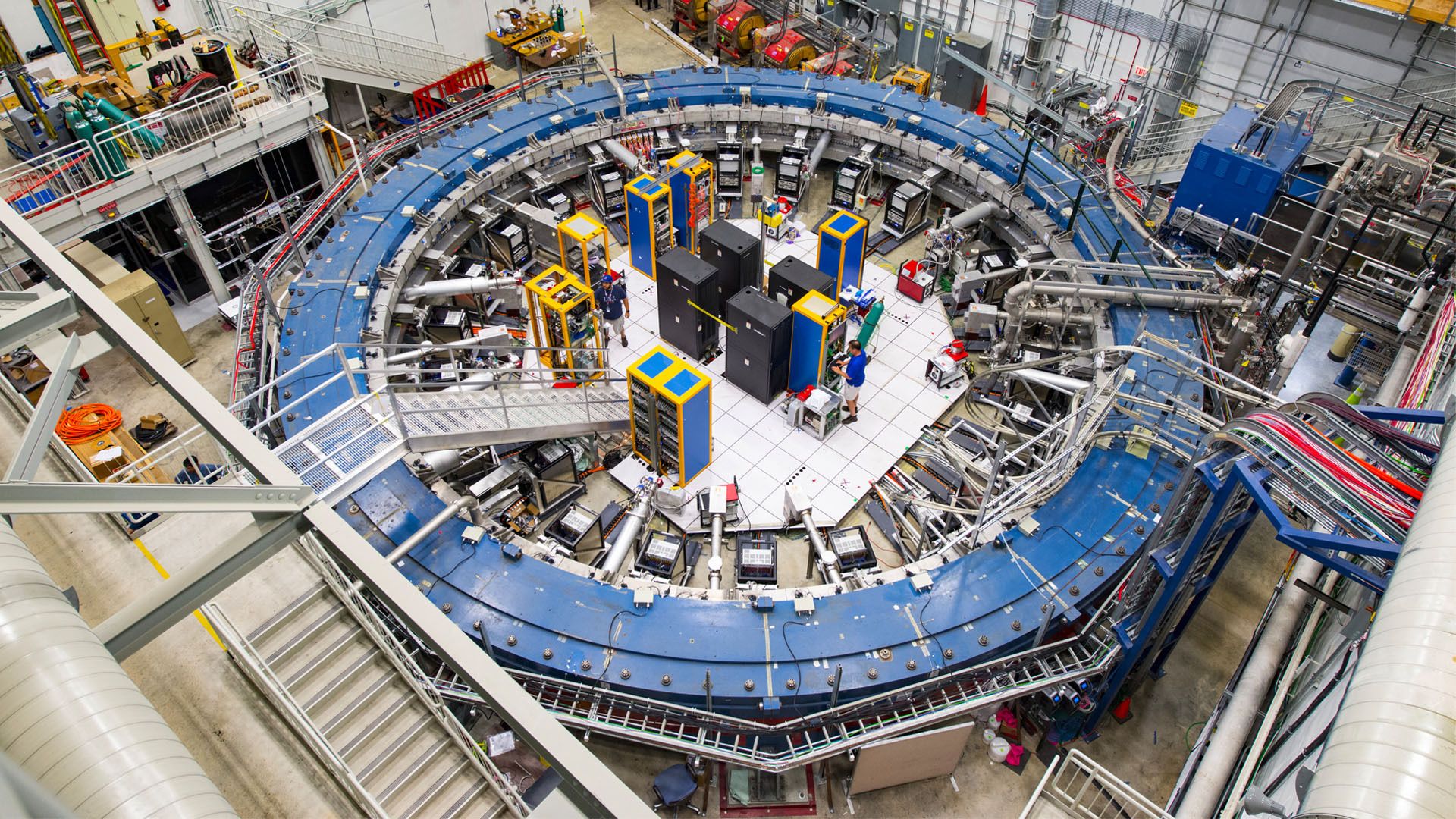

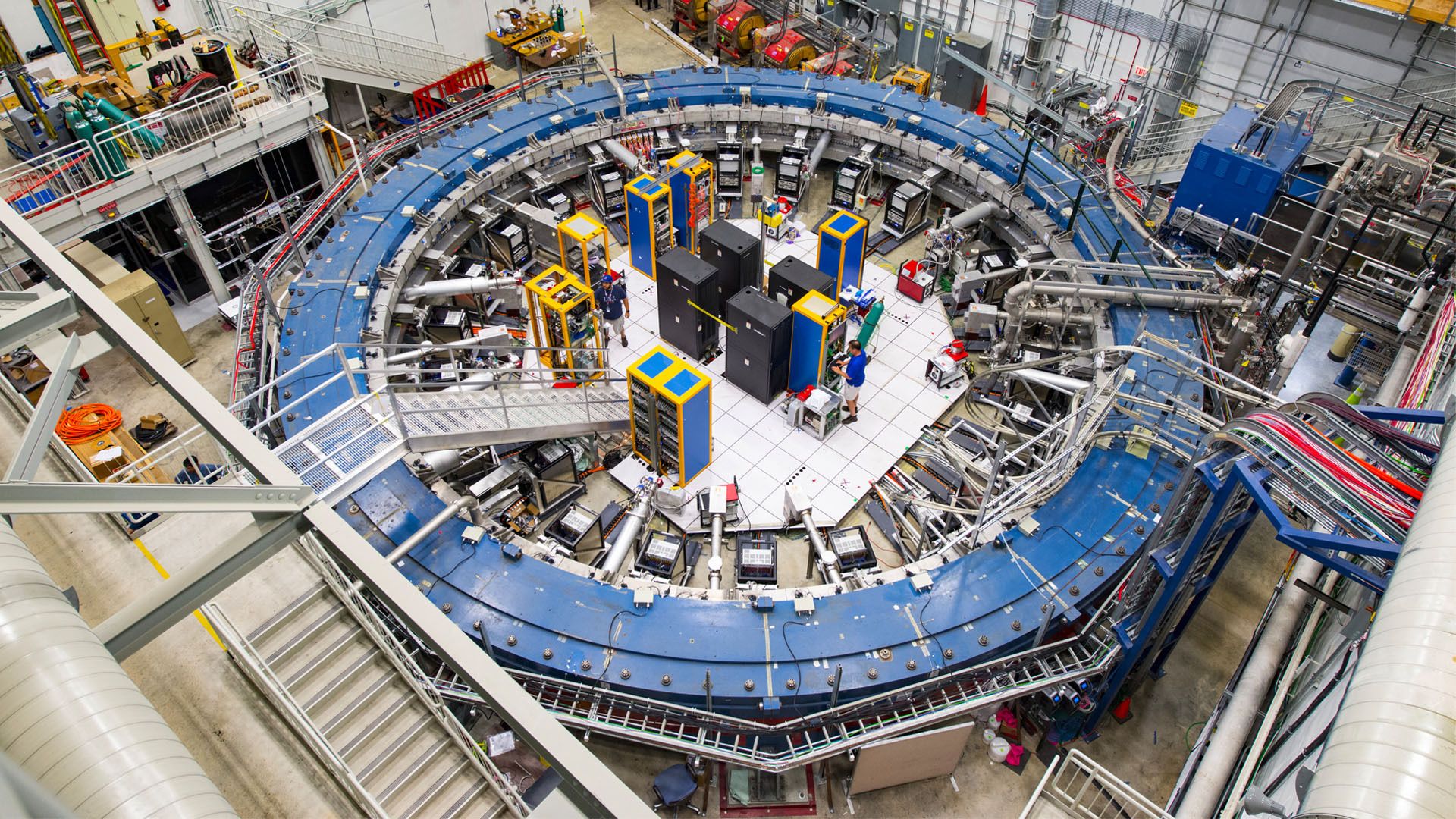

What this means for businesses. | | | | | | 4. So much depends upon the wobble of a muon |  | | | The Muon g-2 ring, at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in Batavia, Illinois. Photo: Reidar Hahn/Fermilab, via U.S. Department of Energy | | | | The results of high-energy physics experiments released on Wednesday open the possibility that a tiny subatomic particle called a muon may act in ways that break the known laws of physics. The big (or very, very, very tiny) picture: The experimental work — while still far from conclusive — underscores the fact that science still has much to learn about the fundamental workings of the universe, and it points the way toward further breakthroughs. Driving the news: In a news conference and virtual seminar on Wednesday, as well as a set of papers published the same day, scientists announced the first results of the Muon g-2 experiments being carried out at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, or Fermilab. - Muons are subatomic particles similar to electrons but possess 207 times as much mass — hence the rather unflattering nickname "fat electrons."

- The particles — which have puzzled scientists since they were first discovered in 1936 — are produced in large amounts during collider experiments at places like Fermilab that involve smashing particles together at high speeds.

What they found: When the muons were sent through intense magnetic fields at Fermilab's Muon g-2 ring, they behaved in ways that didn't quite line up with theoretical predictions, wobbling more than expected. - Anytime nature throws us a curveball, scientists take notice, and the fact that the Fermilab experiments lined up with similar work at Brookhaven National Laboratory in 2001, which has long puzzled researchers, is notable.

- The experiments suggest the Standard Model — physics' fundamental theory about how particles interact with each other — may be far from complete.

The catch: The scientists behind the experiments reported that the results had a 1 in 40,000 chance of being a fluke — pretty good, but still short of the certainty required to claim an official discovery in physics. The bottom line: Today's results represent just 6% of the data ultimately expected to come from the Fermilab muon experiments in the years to come, which means plenty more time for new revelations — and plenty more work for high-energy particle physicists. |     | | | | | | 5. Worthy of your time | | Medium's OneZero — a science and tech publication I helped start before I came to Axios — is largely closing today, so I asked departing editor-in-chief Damon Beres to pick some of his favorite stories. Homeless in the shadow of Apple's $5 billion campus (Brian J Barth) - Just half a block from the $2.1 trillion company's spaceship-like headquarters is an encampment of tents and tarp homes — a potent symbol of Silicon Valley's inequality.

Your DNA test could crack a cold case (Emily Mullin) - OneZero's excellent biotech reporter on how consumer DNA databases are being used to solve decades-old crimes.

The privileged have entered their escape pods (Douglas Rushkoff) - One of the best writers on the social implications of tech explores how the pandemic gave us an early glimpse of the way the very rich can use technology to wall themselves off from chaos.

The influencer and the hitman (Ian Frisch) - One of my favorite parts about OneZero was its willingness to go long on strange corners of tech, and this feature — about a feud over an internet domain name that led to a shooting — does that perfectly.

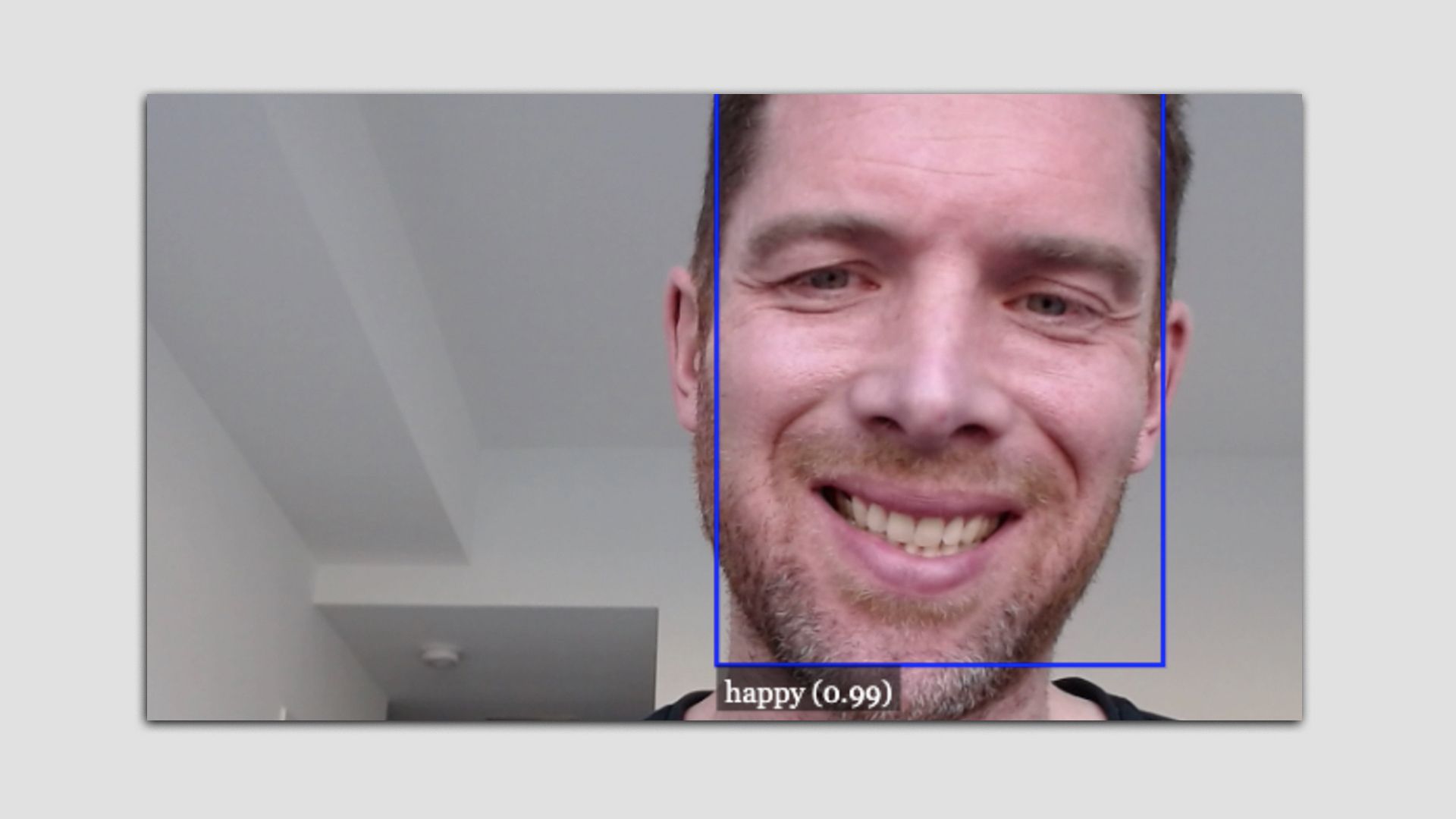

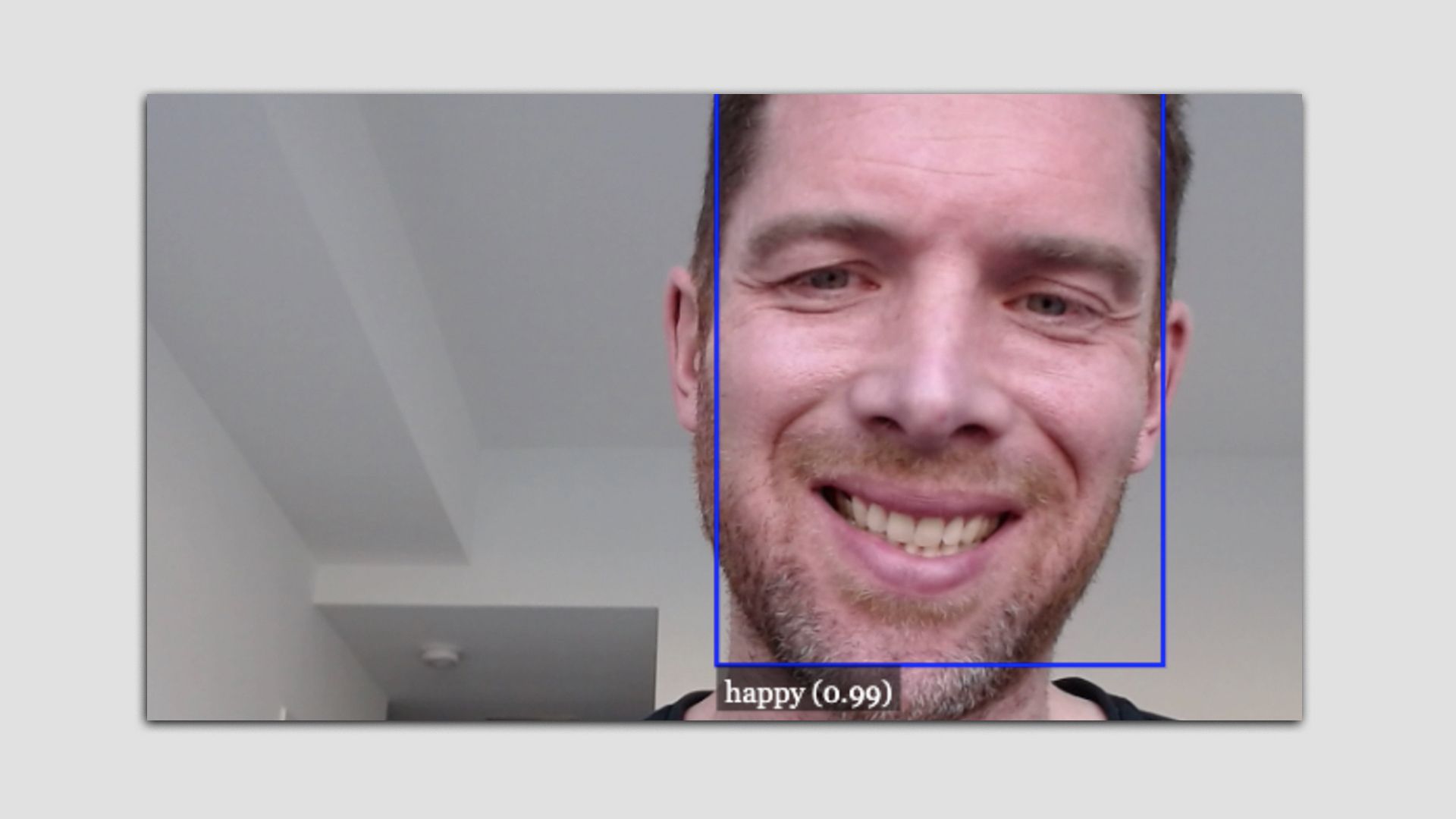

|     | | | | | | 6. 1 AI thing: The perils of emotion recognition |  | | | I am 99% sure I am happy. Photo: Screenshot of me playing the Emojify game | | | | New AI tools purport to be able to identify human emotion in images and speech patterns. Why it matters: Prompted in part by the push of the pandemic, tech companies have been advertising emotion recognition programs, but experts warn they may not work — and may be misused. How it works: Emotion recognition software is meant to do just that — use decades-old psychological research about how humans express emotions and recognize it in image, video or even in speech. The catch: There are serious concerns about how effective emotion recognition AI really is and whether it can even be used ethically. - A multidisciplinary team led by University of Cambridge professor Alexa Hagerty recently produced the Emojify Project, which allows users on the web to try out emotion recognition tech for themselves.

- It's not hard to "fool" the system by producing a less than real facial expression that corresponds to one of the six supposedly universal emotions conveyed by all human beings — like the "smile" I'm presenting in the picture above this piece.

What they're saying: In a piece published earlier this week in Nature, AI ethicist Kate Crawford argued the technology should be regulated because it can draw "faulty assumptions about internal states and capabilities from external appearances, with the aim of extracting more about a person than they choose to reveal." - Last week my Axios colleague Ina Fried broke a story about a digital civil rights group asking Spotify to abandon a technology it has patented to detect emotion, gender and age using speech recognition.

The bottom line: The two questions we should ask about emerging technology are: does it work? And should we use it? - To put it in terms computers might recognize, the answer so far is: 🤷.

|     | | | | | | A message from PwC | | Why 44% of U.S. workers would willingly give up 20% of their pay | | |  | | | | Some workers, especially those who are younger, are more likely to accept smaller pay increases for unlimited vacation and mental health benefits, according to PwC's Workforce Pulse Survey. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1300, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment