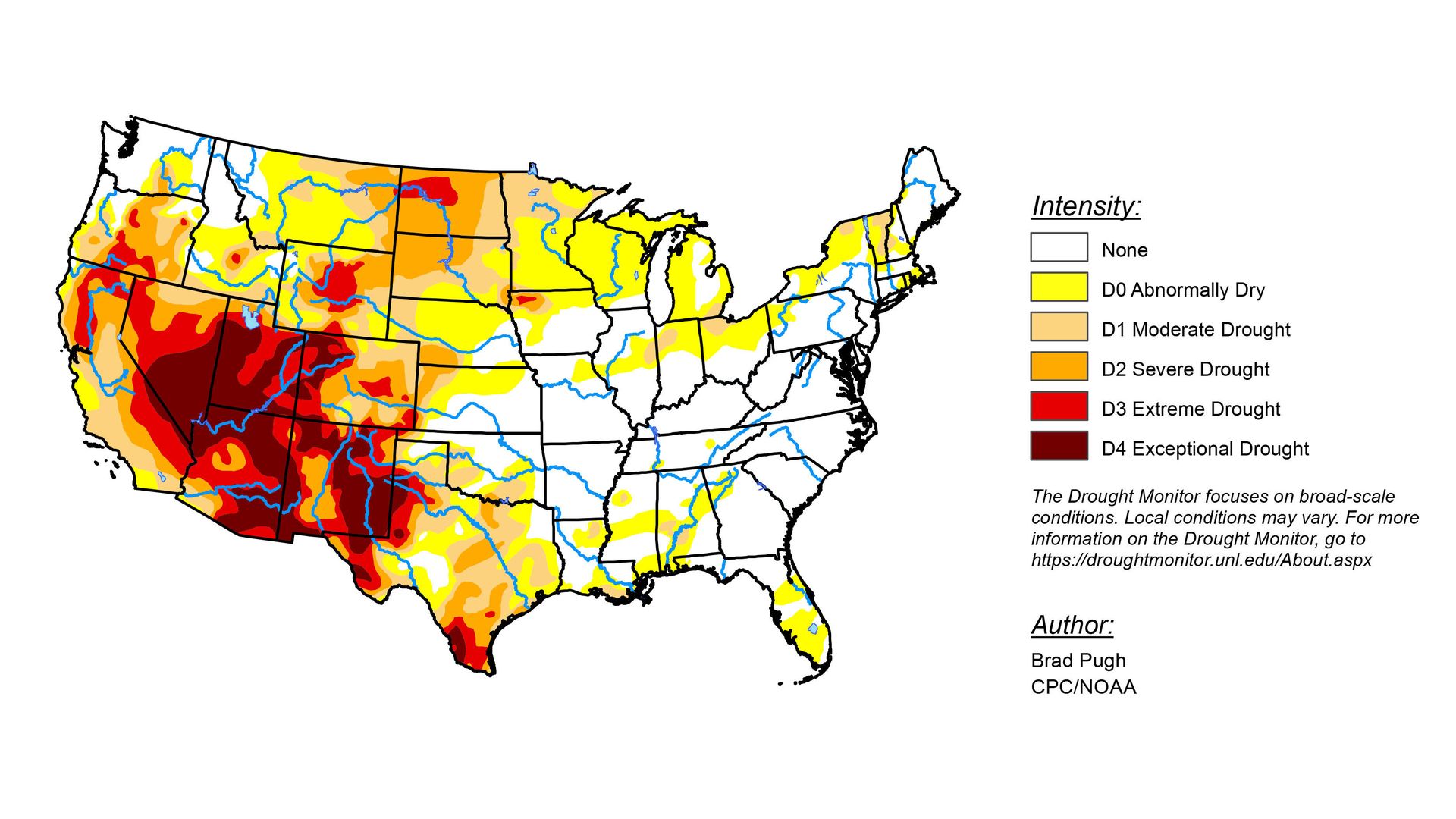

| | | | | | | Presented By J.P. Morgan's Innovation Economy Team | | | | Axios Future | | By Bryan Walsh ·Mar 24, 2021 | | Welcome to Axios Future, where no matter how bad your day has gone, at least you're not the captain of the beached container ship Ever Given. (See item #6.) Today's Smart Brevity count: 1,765 words or about 6½ minutes | | | | | | 1 big thing: A very, very, very dry future for the U.S. West |  | | | Photo: Justin Sullivan/Getty Images | | | | The American West is in the midst of a punishing drought, and long-term conditions are only expected to get worse. Why it matters: Much of the West has a deep history of decades-long "megadroughts" — and that was before the added drying effects of climate change. But with population in the region projected to continue growing, both water demand and carbon emissions risk an arid future for the West. By the numbers: According to the U.S. Drought Monitor, nearly 40% of the West is currently in a state of extreme or exceptional drought, the two most severe categories, and barely 10% of the region is altogether drought-free. - And conditions aren't likely to improve in the near future given the ongoing contributions of climate change. NOAA's most recent Seasonal Drought Outlook predicts persistent dryness west of the Rockies, save for the Pacific Northwest, with drought affecting 74 million Americans.

Where it stands: The driest parts of the American West are already in the grips of a "megadrought," defined as a prolonged drought lasting two or more decades. - The ongoing drought is the result both of reduced precipitation, including less of the winter snowfall that replenishes water reserves, and punishingly high temperatures, which strips the soil of moisture.

The big picture: The American West has a long history of recurring megadroughts that dates back to well before humans started putting carbon into the atmosphere. - A study published last year used moisture-sensitive tree-ring chronologies to find evidence — backed by historical documents of the era — of a multidecadal megadrought in the U.S. Southwest during the 16th century.

- That megadrought was the worst in the region for at least 1,200 years — with the second-worst occurring over the past 20 years.

What to watch: Drought is a product of how little rain might fall and how hot temperatures become, but also of how much water humans are taking from the environment. This means that we're adding more and more people to the very region in the U.S. that has both a history of extreme, multidecadal drought and is set to get drier in the years to come thanks to climate change. Yes, but: Total water withdrawals in the U.S. actually declined 25% between the peak in 1980 and 2015 — one sign of our ability to decouple growth from water use. The bottom line: Multiple past civilizations have met their demise in part due to megadroughts, but with smarter water management and climate action, that doesn't have to be our fate. |     | | | | | | 2. American dry |  | | | U.S. Drought Monitor for March 16 for the continental U.S. Credit: The U.S. Drought Monitor is jointly produced by the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Map courtesy of NDMC. | | | | The most recent U.S. Drought Monitor shows two-thirds of the continental U.S. — and nearly all of the West — in at least some state of drought. Details: The current drought began last year, which was the driest on record for Utah and Nevada, and among the driest for states like Colorado. - "By intensity, it would be about as bad as the U.S. Drought Monitor has shown in the last 20 years," climatologist Brian Fuchs of the National Drought Mitigation Center told USA Today recently.

|     | | | | | | 3. Government by democratic lottery |  | | | Illustration: Eniola Odetunde/Axios | | | | A group is putting forward a unique way to break U.S. political gridlock — replace legislators with ordinary citizens chosen by democratic lottery. Why it matters: Government by democratic lottery may seem extreme — but so is the current period of partisan gridlock, which has made it increasingly difficult for the government to tackle long-term problems. How it works: Instead of regularly electing legislators, democratic lotteries would have representatives in legislative bodies chosen at random from the citizen body, albeit with adjustments to be made for the final selection to represent the demographic and ideological makeup of the population. - The system is a throwback to how democracy worked at times in ancient Athens, where citizens — or at least free male citizens — were chosen by lot for political office.

Context: The Athenians used democratic lotteries because they believed elections inevitably led to corruption and division, according to Adam Cronkright, a coordinator at the democratic lottery group of by for*. - With this system, "there are no stump speeches, no attack ads, no campaigns, no political parties, because none of that matters with a democratic lottery," he says.

Examples: This past fall, of by for* convened a citizens' panel in Michigan of 30 people chosen by democratic lottery. - Citizens on the panel — who had vastly different political backgrounds — met remotely to debate action on COVID-19, one of the most divisive issues facing the country today.

- Despite their divisions, members were able to debate the issues and come up with policy recommendations that had over 70% support of the panel — significantly higher than much of what's passed in a deeply divided Congress.

The catch: Beyond the constitutional changes that would be required to put any democratic lottery in place, the sheer complexity of the U.S. government goes far beyond what citizen-legislators in ancient Athens had to face. - Trying to ensure that a democratic lottery selects a true cross-section of the American public would be a logistical and judicial headache.

Yes, but: Removing elected representatives would cut off the oxygen of a growing number of politicians who seem more interested in social media posting than governing. The bottom line: Americans are accustomed to viewing the health of their democracy through the prism of elections, but coming after a year when the U.S. had the highest voter turnout in decades but remains dysfunctional, we may need to rethink that. |     | | | | | | A message from J.P. Morgan's Innovation Economy Team | | What leaders of mid-sized companies should expect | | |  | | | Many experts believe that 5 trends will help reshape the business landscape. - These trends include: a booming U.S. economy, an uptick in challenges to hiring top talent, and more advantages to selling a business.

J.P. Morgan Chase's Private Business Advisory explains these trends. | | | | | | 4. COVID testing in a post-vaccine world |  | | | Photo: Axios | | | | Far from scaling back testing, the U.S. needs to ramp up rapid COVID-19 tests even as it distributes vaccines, health experts told me at an Axios event today. Why it matters: We're still a long way from enough people receiving and accepting vaccines to fully curb the pandemic, and more ubiquitous testing — especially cheap rapid tests — can help ensure a safer reopening even as the virus continues to circulate. What they're saying: "[I]n the midst of a pandemic, we can switch the purpose of testing from just purely a diagnostic test to actually a test that is going to help mitigate spread at the community level," Harvard epidemiologist Michael Mina told me. - "The only way to make that a reality is to get the tests away from being prescription-use only, make them smaller, simpler and tests that people could be using at home," he added.

How it works: As I've written many, many, many times, the way we've done testing during the pandemic — focusing on expensive PCR lab tests that can take days to return results — is of little use for giving people truly actionable information about their COVID status. - Mina has been pushing cheap, rapid tests that, while somewhat less accurate than PCR tests, can deliver results quickly enough and frequently enough for people to act on.

- "If people walking into [a] building use a test at home before work or at the doorway before school, whatever that might be, it can reduce any chances of spread, say, by 90%," says Mina. "And that is a major win."

Of note: A paper published yesterday in Science reviewed a mass rapid testing plus isolation program in Slovakia that helped reduce the prevalence of positive tests by more than 50% in a week, even as schools and workplaces remained open. The bottom line: Opening without greatly expanding testing — which is what much of the U.S. is doing right now — is a dangerous combination, especially with more contagious virus variants becoming increasingly prevalent. |     | | | | | | 5. Worthy of your time | | The geopolitical fight to come over green energy (Helen Thompson) - We have barely begun to grapple with the economic and geopolitical challenges that will accompany the necessary shift off fossil fuels.

Quantum computing ethics and hype: the call is coming from within the house (Scott Aaronson) - As the money in the quantum computing sector grows, so does the tendency of companies and researchers to hype their work — until, like in quantum physics itself, it can feel as if there's no solid ground to stand on.

Could an accident have caused COVID-19? (Alison Young — USA Today) The world of John McPhee (The New Yorker) - A look back at the work of the great nonfiction chronicler, whom I was lucky enough to study under at college, where I learned this important writing lesson: You can never have enough index cards.

|     | | | | | | 6. 1 globalization thing: Canal lock |  | | | Workers next to a container ship that was hit by strong winds and ran aground in the Suez Canal, Egypt. Photo: Suez Canal Authority via Reuters | | | | Traffic at the Suez Canal is blocked because a huge container ship ran aground. Why it matters: The Suez accounts for approximately 30% of container shipping volumes, and blocking it for even a short time will cause oil prices to rise — and remind us that the entire global economy relies on really, really big ships. Driving the news: The Ever Given was heading from China to the Netherlands when it ran aground yesterday after getting caught in poor visibility and high winds from a sandstorm. - Because the 1,312-foot ship found itself wedged across the width of the canal, traffic through the all-important maritime chokepoint may be disrupted for days.

- And almost as importantly, the accident gave birth to many, many memes.

The big picture: Even as COVID-19 brought the virtual realm to the forefront, the world economy still chiefly runs on actual, physical stuff — and much of that actual, physical stuff is brought to us in the holds of vast container ships. - The pandemic has disrupted the flow of global trade, with consumers in the U.S. ordering so many goods online from manufacturers in China that the world was running low on shipping container boxes.

By the numbers: There are currently over 5,000 container ships operating around the world, with more than 20 million 20-foot-equivalent cargo containers. - As vast as the oceans are, much of the world's shipping — and especially the oil that keeps the economy running — flows through just seven major maritime chokepoints, including the Suez Canal.

- While e-commerce grew by 44% in 2020 as we increasingly shopped from home, all those online orders would be useless without container ships to carry them out.

The bottom line: Apparently, all it takes to put a spoke in the wheel of globalization is one very large ship in one very wrong place. |     | | | | | | A message from J.P. Morgan's Innovation Economy Team | | How CEOs and CFOs can manage digital disruption | | |  | | | | A recent survey of 3,600 companies has uncovered a game-changing fact: 63% of them face significant disruption. Why it's important: To stay ahead, companies must welcome change with positive, innovative and customer-centric approaches to rapid shifts. J.P. Morgan Chase explains how. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1300, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

Post a Comment

0Comments