| | | | | | | Presented By Babbel | | | | Axios Science | | By Alison Snyder · Jan 12, 2023 | | Thanks for reading Axios Science. This week's newsletter is 1,619 words, about a 6-minute read. | | | | | | 1 big thing: What's slowing down science |  | | | Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios | | | | Discoveries that push science in new directions are happening less often than they did in the last century, according to a new finding that will frame debates about how (and how much) to try to spur this type of research. Why it matters: Scientific advances fuel economies and contribute to improving human health and life — and they are increasingly at the center of geopolitics. Countries are strengthening their scientific institutions to compete for top talent and scientific and technological dominance. - "What we understand about those institutions and how to make them better really has the potential of making a big impact over the long run on who we are as a society and on human welfare," says Pierre Azoulay, an economist at MIT who studies technological innovation.

What's new: A study of 25 million scientific papers published between 1945 and 2010 and 3.9 million patents (from 1976 - 2010) found the proportion of "disruptive" papers being published fell. - Previous analyses have found patents, papers, Nobel Prizes and grant applications have become less novel than earlier work and less likely to bring together existing knowledge in new ways, both of which support innovation, the study authors write in the journal Nature.

- But the new study takes a broader look at the question.

How it works: The researchers gauged a paper's "disruptiveness" using the consolidation-disruption (CD) index that captures how a paper is cited. - Citations of a paper that builds on earlier work (consolidates knowledge) typically also cite that earlier work. But a paper is considered disruptive if the papers that later cite it don't reference the same papers in the original paper — the new finding replaces the old in the network of knowledge.

- The researchers also analyzed the words in papers and found older papers were more likely to be written in terms of discovery ("form," "measure" and "determine") whereas newer ones contained language of improvement.

- They found a decline in disruptiveness across fields but it was greatest in the social sciences and least in the life sciences.

Yes, but: The number of disruptive papers held steady over the decades. That helps to reconcile the findings with headline-making discoveries about advancing AI, blackhole photographs and the rapid development of COVID vaccines, says Russell Funk, a sociologist at the University of Minnesota and a co-author of the new study. The optimistic take: "We're still asking new questions at a remarkably consistent rate and solving problems at a higher rate," says Dashun Wang, who directs the Center for Science of Science and Innovation at Northwestern University's Kellogg School of Management. The more pessimistic view: "The fact that the absolute number is not falling can be taken as a positive ... but the fall in proportion is pretty drastic and opens a lot of questions," Azoulay says. - The big question: "We have more knowledge to build on than ever so why isn't innovation accelerating?" Funk says.

- The big picture: For many, disruption — coveted and promoted in the culture of Silicon Valley — carries a positive connotation and is increasingly synonymous with progress.

- But it can't be all there is to science, Wang says. "There needs to be people who ask questions and people who solve problems. Problem solvers are probably viewed as less disruptive but it doesn't mean they are not as valuable."

- He points to Einstein's theory of general relativity and the Nobel Prize-winning LIGO experiments that test it.

- "There are super important discoveries that aren't disruptive but advance a field or make a technology viable. You really need both," Funk says, noting the index's original name was consolidation-destablization. "If I had my way, I wouldn't call it disruption."

Go deeper. |     | | | | | | 2. Study: Young scientists thrive in China talent program |  | | | Illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios | | | | Young Chinese scientists recruited back to China through a government talent program went on to publish more scientific papers than their counterparts who remained overseas, according to an analysis recently published in the journal Science. Why it matters: "If we perceive the 20th century as a century of international trade and manufacturing, the 21st century is more about a knowledge-based economy and brain power truly matters a lot," says Yanbo Wang, who studies innovation policy at the University of Hong Kong and is a co-author of the study. - Policymakers will have to figure out which tools help to recruit and retain talent, he says.

- The study authors point to "access to greater funding and larger research teams" as driving the productivity of scientists who received funding from China's Young Thousand Talents (YTT) program.

Background: The YTT program began in 2010 and offered more than 3,500 young researchers (typically under 40 years old) funding and benefits to relocate full-time to China between 2011 and 2017. Foreign-born scientists are eligible for grants but the program has largely attracted Chinese-born researchers who received their graduate degrees abroad. - The talent recruitment program is one of many in China and a branch of the Thousand Talents Plan, a large, loosely defined — and controversial — program that began in 2008 with the aim of recruiting top-caliber scientists to work with China.

Details: Wang and his colleagues studied 339 young Chinese scientists who accepted YTT offers and returned to China, and 73 who rejected the offers. - They analyzed the number of annual publications from the researchers in the five years before they returned to China, and by that metric, the group that accepted the YTT grants was in the top 15% of all early-career scientists in the U.S. with Chinese surnames, the authors reported.

Yes, but: The researchers who didn't accept the YTT grants were on average in the top 10% of scientists — what the authors define as "top-caliber" — and were more likely to have faculty appointments than to work in someone else's lab. - The scientists who stayed also had more research funding than those who accepted YTT grants.

But, but, but... The researchers who returned to China published 27% more papers — and more papers in high-impact journals — in the seven years after they went back, compared to those who stayed in the U.S. - They were also more likely to be the last authors, an indication they led the research as principal investigators (PIs) of their own teams.

- "They didn't have the opportunity to become PIs in the U.S. and EU but in the YTT they were able to become independent researchers," Wang says, adding the data reflects the difficulty young researchers can have in accessing funding in the U.S. and European Union.

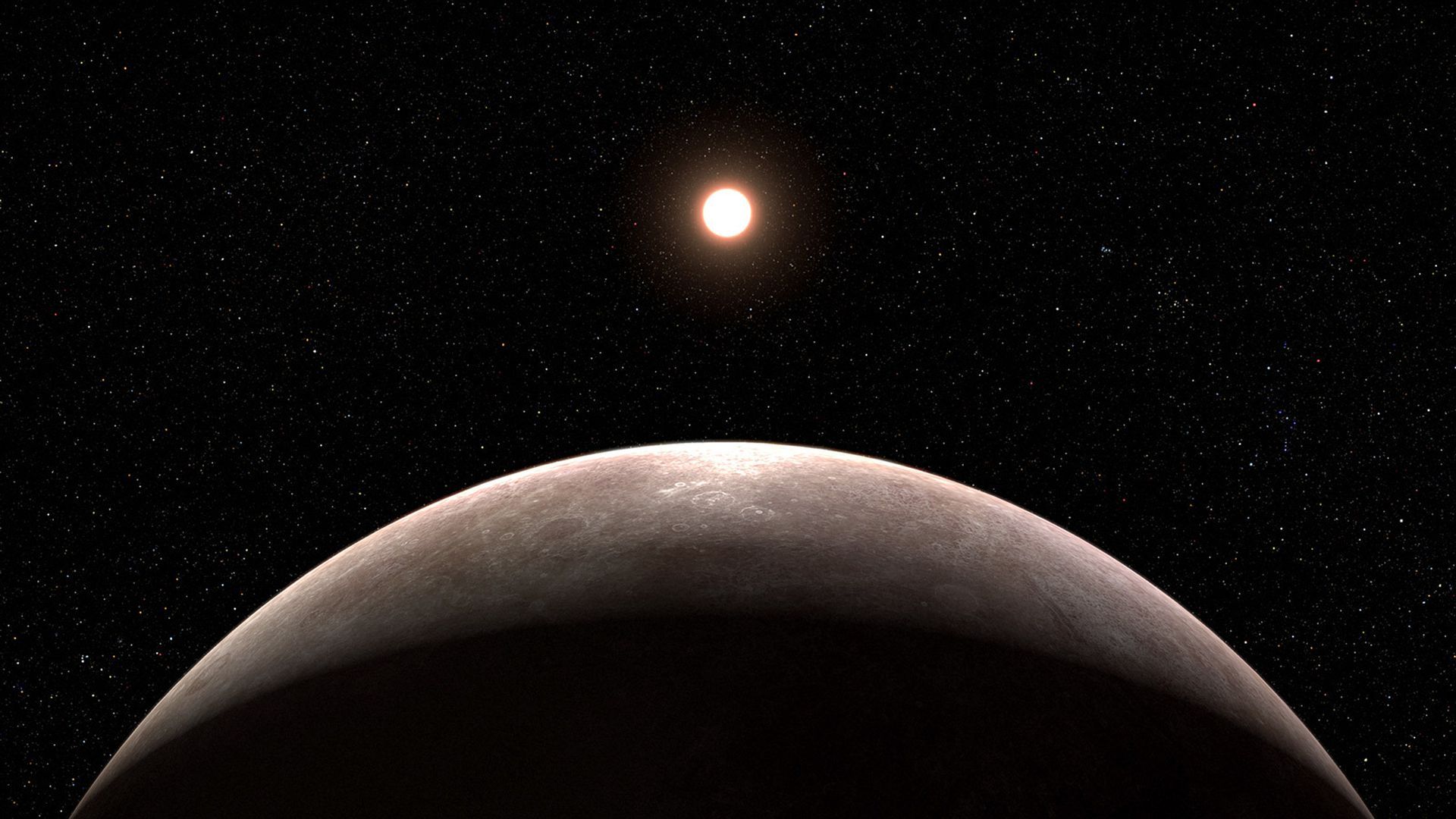

Read the entire story. |     | | | | | | 3. JWST confirms its first alien planet, and it's the size of Earth |  | | | Artist's illustration of the planet LHS 475 b. Image: NASA/ESA/CSA/Leah Hustak (STScI) | | | | The James Webb Space Telescope has confirmed its first planet orbiting a distant star, and it's a rocky world just about the same size as Earth, Axios' Miriam Kramer writes. Why it matters: Part of the scientific value of the JWST is its ability to characterize alien planets. This finding opens the door to learning more about what the atmosphere of this planet could be. What they found: Researchers turned the JWST's powerful eye on a star system suspected to have a planet about 41 light-years away. - NASA's TESS spacecraft first hinted at the world's existence, but the JWST's new observations confirmed the planet — named LHS 475 b.

- The planet orbits its star — which is smaller and cooler than the Sun — every two days, and the data suggests the world is hundreds of degrees warmer than the Earth.

- While the planet has an incredibly close orbit, because the star is smaller and cooler, the planet could still have an atmosphere, according to NASA.

The intrigue: Figuring what — if any — atmosphere envelopes LHS 475 b is going to take a bit longer for scientists to piece together. - The research team has been able to rule out a few different atmospheric compositions. They think LHS 475 b doesn't have an atmosphere that's thick and methane-rich, like Saturn's moon Titan, but it's possible the planet has an atmosphere that is entirely made of carbon dioxide.

- The team should get more information with follow-up observations this summer.

|     | | | | | | A message from Babbel | | Spend 10 minutes a day escaping to a new world | | |  | | | | Jumpstart your year with Babbel, the learning platform that offers daily language lessons for real-world use. You get to access: - Podcasts, games, videos and articles.

- Live online classes with top teachers.

- Tailored lessons with topics you pick.

Speak a new language in just 3 weeks. | | | | | | 4. Worthy of your time |  Data: Exxon; Chart: Axios Visuals Exxon's climate research accurately projected global warming, study finds (Andrew Freedman — Axios) The new soldiers in propane's fight against climate action: television stars (Hiroko Tabuchi — NYT) XB what? BQ huh? Do you need to keep up with Omicron's ever-expanding offspring? (Helen Branswell — STAT) |     | | | | | | 5. Something wondrous |  | | | A fresco in the house of the Vettii, in the archaeological excavations of Pompeii, reopened to the public after the restoration. Photo: Marco Cantile/LightRocket via Getty Images | | | | People visiting Italy's Pompeii archeological park can again see the extravagant House of the Vettii, which was reopened to the public this week after 20 years of restoration, Axios' Laurin-Whitney Gottbrath writes. Why it matters: The site showcases why some archaeologists think the layer of ash that buried the city in 79AD when Mount Vesuvius erupted may have both damaged and helped preserve Pompeii's stunning frescoes, shielding them from light and the elements for centuries. - It also offers a glimpse into how the uber-rich in Pompeii lived before the city disappeared under the volcanic ash.

The big picture: Researchers believe the House of Vettii was owned by two formerly enslaved brothers (there's debate about whether they were brothers or just enslaved by the same person) who become rich by trading wine. - It's known as Pompeii's Sistine Chapel because of its abundant and well-preserved frescoes and mosaics.

- "We're seeing here the last phase of the Pompeian wall painting with incredible details, so you can stand before these images for hours and still discover new details," Pompeii's director, Gabriel Zuchtriegel, told AP.

- "You have this mixture: nature, architecture, art. But it is also a story about the social life of the Pompeiian society and actually the Roman world in this phase of history," Zuchtriegel added.

The intrigue: Considered a UNESCO World Heritage site along with the nearby areas around Herculaneum and Torre Annunziata, Pompeii shows "the evolution of archaeological practices, conservation techniques and approaches to presentation over the past two centuries." |     | | | | | | A message from Babbel | | Broaden your ability to connect with anyone | | |  | | | | Explore up to 14 languages with Babbel, the expert-led app helping users learn to have real-world conversations in as little as 3 weeks. - Lessons even include context tips that offer useful cultural knowledge to help you better understand the words you learn.

Get up to 55% off for a limited time. | | | | Big thanks to Laurin-Whitney Gottbrath for contributing to and editing this edition, to Andrew Freedman for contributing this week, to Aïda Amer on the Axios Visuals team and to Carolyn DiPaolo for copy editing. |  | | Are you a fan of this email format? Your essential communications — to staff, clients and other stakeholders — can have the same style. Axios HQ, a powerful platform, will help you do it. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

To stop receiving this newsletter, unsubscribe or manage your email preferences. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment