| | | | | | | | | | | Axios Generate | | By Ben Geman and Andrew Freedman · Nov 28, 2022 | | 👋 Welcome back! Today's newsletter has a Smart Brevity count of 1,187 words, 4.5 minutes. 📉 "Oil prices fell to near their lowest levels this year on Monday as street protests against strict COVID-19 curbs in China, the world's biggest crude importer, stoked concern about the outlook for fuel demand." (Reuters) 🎶 Today marks 45 years since funk pioneers Parliament dropped the album "Funkentelechy vs. the Placebo Syndrome," which provides today's intro tune... | | | | | | 1 big thing: Pacific NW heat wave was a warning |  | | | Illustration: Brendan Lynch/Axios | | | | The 2021 heat wave in the Pacific Northwest, which killed hundreds of people in the U.S. and Canada, was a harbinger of a new generation of climate disasters to come, a new study finds, Andrew writes. Why it matters: In the most comprehensive analysis to date of what made the heat wave so extreme, scientists ruled out the possibility this was a "black swan" event, which is unpredictable and unlikely to recur. The big picture: Instead, the new study in Nature Climate Change shows that amplifying feedbacks between factors such as unusually dry soils and a highly contorted jet stream added to the effects of long-term climate change. - This dialed up the heat to unprecedented levels for the region.

- The wavy jet stream pattern, itself tied to climate change, helped give rise to a record-strong heat dome that parked itself over British Columbia and the Northwest U.S. in early summer.

- The study finds that in the Northwest but likely other areas as well, multiple trends are pushing the climate into a zone where such extremes are far more likely.

- "The background warming, the atmospheric dynamics, and the soil moisture deficiency interacted in a way that amplified this event beyond a normal extreme," study coauthor Kai Kornhuber, a senior fellow at the German Council on Foreign Relations, tells Axios in an interview.

Between the lines: In the 1950s, the study states, the prospect of such a heat wave occurring in the Pacific Northwest was virtually impossible, but climate change had transformed that into a 1-in-200-year event by 2021. - Kornhuber says that while it is "encouraging" that models used for weather forecasting captured the heat wave's likely development and severity, climate models used to conduct risk assessments for heat hazards in coming decades may be flawed.

- If they are missing some of the feedbacks the study identifies, climate models could underplay the risk of a repeat or even worse event.

- Looking ahead, if climate change is held to 2°C above the pre-industrial average, 2021-type Pacific Northwest heat events are likely to take place at a frequency of about once every 10 years.

Yes, but: Even if all existing emissions pledges are met, the world is currently headed for greater than 2°C of warming. What they're saying: "Our study supports a very direct conclusion that extreme heat like this will only become more and more likely — both in this region and across the globe, especially where heat stress is already extremely high — as more fossil fuels are burned," lead author Samuel Bartusek of Columbia University told Axios via email. |     | | | | | | 2. The politics of easing sanctions on Venezuela |  | | | Illustration: Shoshana Gordon/Axios | | | | 🚨Interesting take alert: Some analysts say Florida's rightward political shift can't be untethered from Biden officials' new decision to ease oil sanctions against Venezuela, Ben writes. Catch up fast: The Treasury Department announced Saturday it's giving Chevron a six-month license to resume oil production and exports there. Officials cited new talks between leftist President Nicolás Maduro and the opposition coalition, and their agreement on humanitarian aid. The intrigue: Republican candidates romped on Election Day this month in Florida, once a swing state that's becoming reliably red. Two Atlantic Council analysts, in a blog post, cited this evolution among the forces behind the move. - "Now that Florida is a reliably Republican state, U.S. policy no longer needs to revolve around the more hard-line interests of voters in the state that is home to over half of [U.S.] Venezuelan immigrants," Jason Marczak writes.

What they're saying: The research firm ClearView Energy Partners said in a note... - "After decisive re-election victories by Florida Republicans like Governor Ron DeSantis and Representative María Elvira Salazar (who represents a significant Venezuelan diaspora), Democrats may see little political upside in keeping a hard line against Caracas when crude supplies are tight."

- The Washington Post explores this, too.

Yes, but: Saloni Sharma, a White House spokesperson, tells Axios via email that "it's because of concrete steps taken like political talks after years of stalemate to restore democracy and a humanitarian agreement for the Venezuelan people." - Treasury's statement notes "longstanding U.S. policy to provide targeted sanctions relief" following tangible steps toward those aims.

- Chevron's resumption of joint venture activities with Venezuela's state-owned PdVSA does not allow the Maduro regime to receive taxes or royalties.

What we're watching: The political fallout and especially the reaction of DeSantis, a potential GOP White House contender. |     | | | | | | 3. Venezuela's crude decline |  Data: EIA; Chart: Will Chase/Axios Venezuela holds massive oil reserves but its production plummeted in recent years amid Trump-era sanctions and other forces, Ben writes. - "Output slumped following sanctions and mismanagement of oil fields and refineries under the socialist rules of Hugo Chavez and Maduro," Bloomberg notes.

- It has rebounded somewhat, reaching 679,000 barrels per day last month in OPEC's data.

Yes, but: Don't look for a return to prior levels of around 3 million barrels per day, at least not for a long time. The FT quotes Francisco Monaldi, a Rice University expert in Latin American energy, saying Chevron's joint ventures could boost production to up to 100,000 barrels in a few months. After that "it will require significant investments, which will take about two years to achieve an additional 120,000 bpd." |     | | | | | | A message from Chevron | | Chevron is working to fuel a lower carbon future. | | |  | | | | We believe the future of transportation can be lower carbon. At Chevron, our renewable diesel, made with bio feedstock, can fuel trucks, trains, heavy-duty equipment and more with lower carbon intensity today. Because we know creating renewable fuels is just as important as putting them to use. | | | | | | 4. Vietnam's VinFast joins expanding U.S. EV pool |  | | | VinFast LLC's VF8s are loaded into a ship for export at a port in Haiphong, Vietnam, on Friday. Photo: Linh Pham/Bloomberg via Getty Images | | | | The Vietnamese EV startup VinFast shipped almost 1,000 California-bound VF 8 models on Friday, marking what the company called the first step in its major push into international markets, Ben writes. Driving the news: "This international export is the first batch of the 65,000 global orders already made for VinFast's VF 8 and VF 9," the company said. Why it matters: It's part of the wider growth of EVs available in the U.S. and elsewhere as startups and legacy automakers bring more models to market. The research firm BloombergNEF, in a report this month, said there were 84 models available in the U.S. in mid-2022, up from 59 at the end of 2020. What we're watching: The company is planning to build a factory in North Carolina that would begin churning out cars in 2024. - VinFast chief executive Le Thi Thu Thuy tells Reuters that vehicles built there would fully qualify for consumer subsidies available under the new climate law.

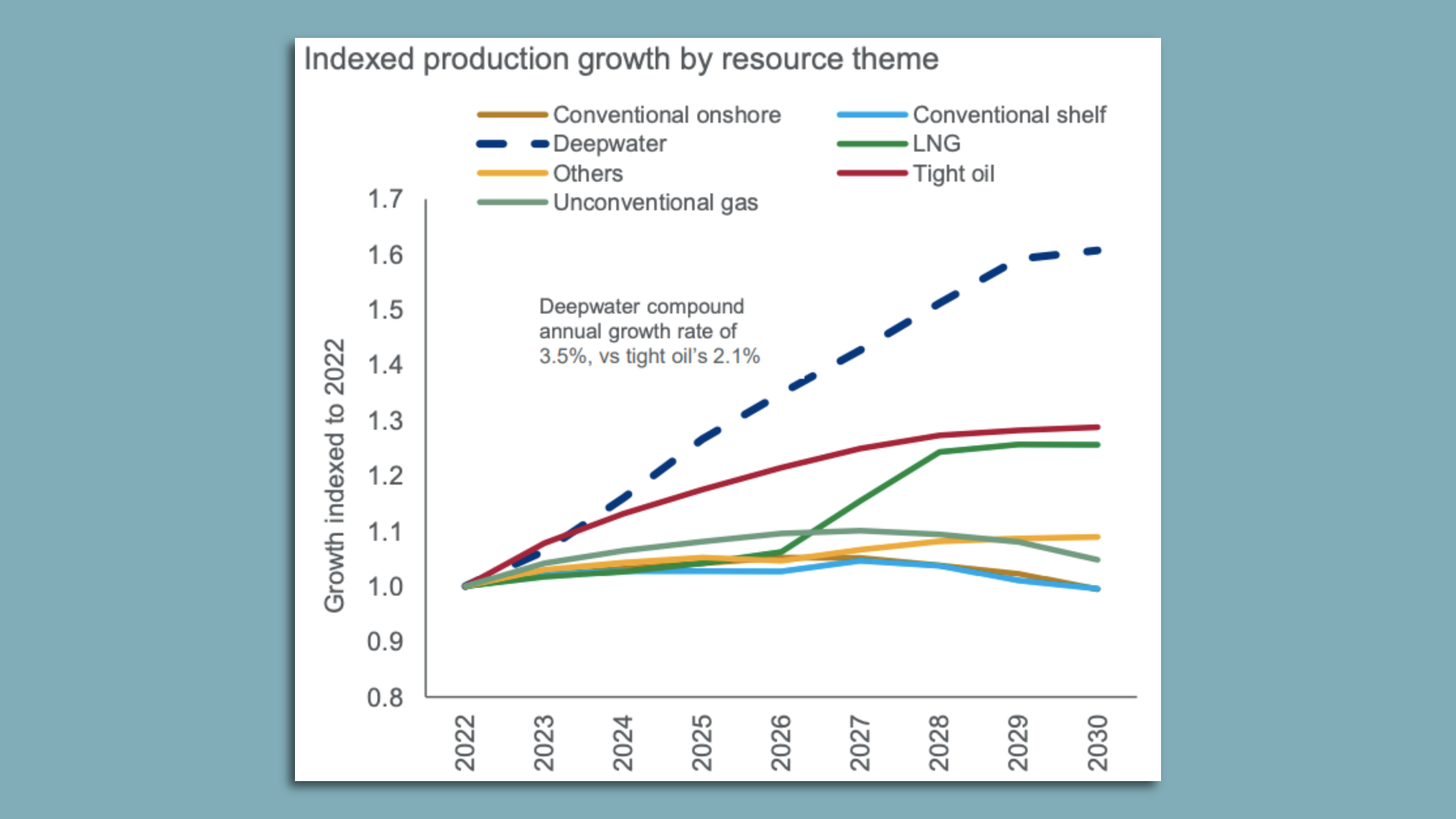

|     | | | | | | 5. Charted: A coming deepwater production surge |  | | | Image courtesy of Wood Mackenzie | | | | Oil from wells in very deep waters (at least 400 meters and often far more) will be the fastest growing type of global crude production this decade, per a new Wood Mackenzie analysis, Ben writes. What's next: The research and consulting firm sees production rising from over 10 million barrels per day this year to over 17 million in 2030, when it will be 8% of total global production. - Major growth areas include Brazil and Guyana, where Exxon is bringing giant fields online.

- Projects in waters at least 1,500 meters will grow most quickly, they estimate.

|     | | | | | | 6. 💬 Quoted | | "I've got a number of members who feel strongly that a 2-2 split is going to further slow projects and a number of other members who sort of think, well, maybe a 2-2 split isn't the end of the world." — Charlie Riedl, executive director for the Center for Liquefied Natural Gas, via BloombergThat's the industry group exec on the drama surrounding the fate of Federal Energy Regulatory Commission Chairman Richard Glick, whose renomination has not advanced yet on Capitol Hill. |     | | | | | | A message from Chevron | | Chevron is working to fuel a lower carbon future. | | |  | | | | We believe the future of transportation can be lower carbon. At Chevron, our renewable diesel, made with bio feedstock, can fuel trucks, trains, heavy-duty equipment and more with lower carbon intensity today. Because we know creating renewable fuels is just as important as putting them to use. | | | | 📬 Did a friend send you this newsletter? Welcome, please sign up. 🙏Thanks to Mickey Meece and David Nather for edits to today's newsletter. We'll see you back here tomorrow! |  | | Your personal policy analyst is here. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters. If you're interested in advertising, learn more here.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment