| | | | | | | Presented By PhRMA | | | | Axios Science | | By Alison Snyder · May 05, 2022 | | Thanks for reading Axios Science. This week's edition is 1,463 words, about a 5.5-minute read. | | | | | | 1 big thing: Rising fertilizer prices highlight soil science |  | | | Illustration: Natalie Peeples/Axios | | | | Skyrocketing fertilizer prices are renewing focus on other tools that could ultimately improve the health of soil and strengthen food production. Why it matters: Shocks to the world's agriculture systems — including droughts fueled by climate change, as well as seed and fertilizer shortages due to conflicts and natural disasters — are likely to become more frequent. Driving the news: The price of fertilizer has climbed around the world, pushing some farmers to apply less nitrogen, phosphorus and potash to their crops, Bloomberg reports. What's happening: In the U.S., rising fertilizer prices may be motivating some farmers to test plant- or microbe-based biological fertilizers being developed by a slew of startups, the WSJ reports. - Farmers may also take another look at new digital agriculture tools to help them use fertilizer and other resources more precisely, says Harold van Es, a professor of soil and water management at Cornell University.

In the near term, alternative fertilizers, cover crops and digital tools could be used to reduce and optimize the use of synthetic fertilizer, which comes with environmental costs, including run off of nitrogen into rivers and aquifers. - Over time, they could help to accumulate nutrients in the soil, improving its health and buffering crops from disruptions, Kaye says.

Details: Regenerative and circular agriculture approaches focus on restoring soil health and recycling and upcycling the resources required for producing food. - The science underlying them progressed over decades as the tools of genetics, biology and chemistry became more sophisticated and less expensive — and people became more interested in the systems that produce their food.

At the University of Minnesota, researchers led by Donald Wyse are developing more than a dozen cover crop plants that can be grown when fields in the upper midwestern U.S. would otherwise sit bare, the NYT's Jonathan Kauffman wrote this week in a profile of Wyse. Those "evergreen crops" can provide farmers with another source of income and soil with organic matter and carbon. - Scientists at Penn State University are looking at whether composted urban food waste combined with animal manure could help reduce the amount of fertilizer needed for crops. Preliminary modeling data of croplands in the Chesapeake Bay region suggests it could without impacting water quality, says Jason Kaye, a professor of soil biogeochemistry at Penn State University.

But, but, but ... Designing agriculture around ecology carries uncertainties for farmers and food supplies. - Nutrients are supplied by the decomposition of cover crop plants and manure — a process that depends on microorganisms, the water available in the soil and soil temperature.

- Those processes are harder to predict than taking a known amount of fertilizer and determining how much nitrogen a field will get, says Kaye, who is developing tools to predict how much of a nutrient a plant or manure will deliver.

A better understanding of soil health is emerging as scientists shift from focusing exclusively on the chemicals in soil to incorporating biology and physics as well, says van Es. - He and others are honing assessments of the indicators in soil that signal its health — a mix of organic matter, how compacted it is, the microbiome of the soil and more.

- In a recent preprint paper, van Es and his colleagues identified bacterial indicators of soil health, based on genetic sequencing.

The catch: Adopting new tools means taking on new costs. The price points matter for farmers, especially those raising food for their own consumption rather than for market. - And, "these systems take a long time to implement. Once you do, they are resilient to shocks," Kaye says. "But they aren't going to help us next year. It takes a decade to build soil organic matter like that."

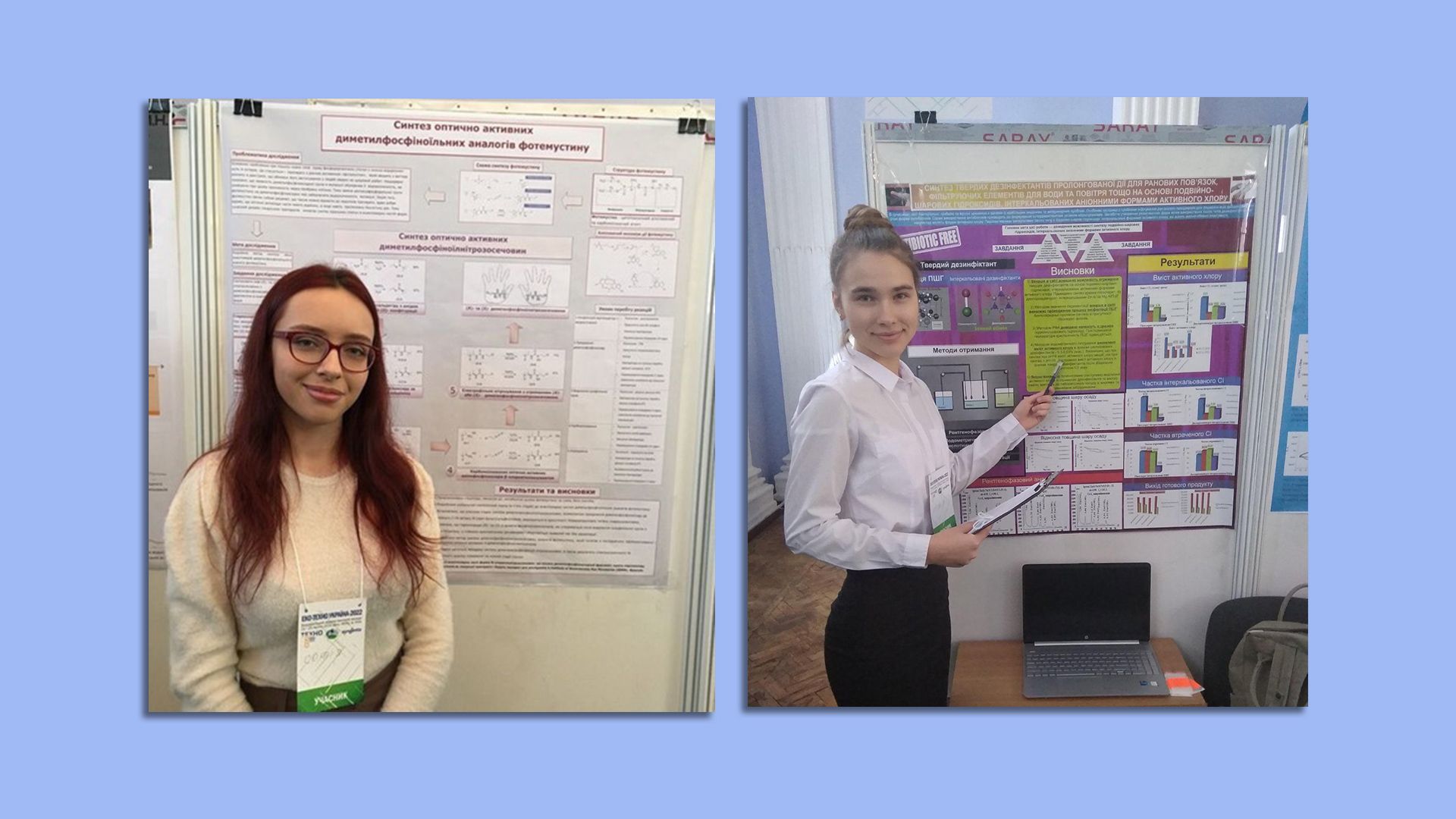

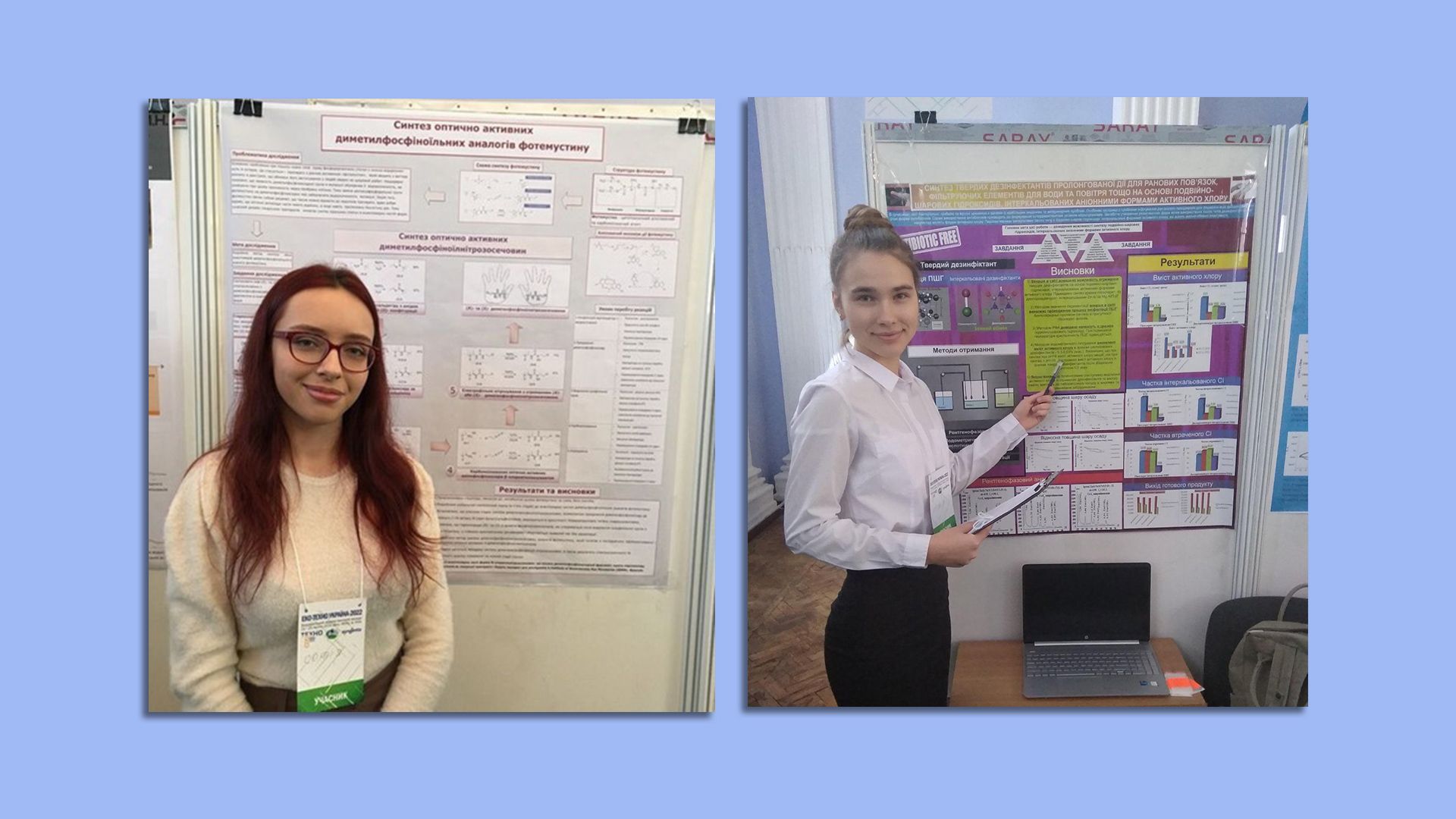

Go deeper. |     | | | | | | 2. Catch up quick on COVID |  Data: N.Y. Times; Cartogram: Kavya Beheraj/Axios "COVID cases are rising in all but four states and Washington, D.C., as Omicron and new, potentially more transmissible versions of the Omicron variant, sweep across the U.S.," per Axios' Tina Reed and Kavya Beheraj. About two in every three children between 1 and 4 years old in the U.S. have been infected with SARS-CoV-2, Smriti Mallapaty reports for Nature. The two Omicron subvariants fueling South Africa's surge can evade antibodies from previous COVID infection, but researchers say vaccinated people "should be better protected," Reuters reports. Immune system proteins involved in producing excess mucus and closing airways in people with allergic asthma appear to also protect them against COVID-19, Tina Hesman Saey reports for Science News. |     | | | | | | 3. Ukrainian science students persist in wartime |  | | | Sofiia Smovzh with her research poster at ISEF in Kiev in February 2022 (on left); Sofiia Timofieieva at Eco-Techno Ukraine fair. Photos courtesy of Sofiia Smovzh and Sofiia Timofieieva | | | | Displaced by war, separated from family and far from home, six students from Ukraine are competing in the world's largest science fair. Details: This week, the students will participate virtually alongside more than 1,750 other finalists in the Regeneron International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF). - The students from Ukraine qualified by competing in a series of regional ISEF-affiliated events, culminating with the national fair in Kyiv.

- That event ended on Feb. 23, cut short by Russia's invasion of the country the next day.

Sofiia Smovzh, a 17-year-old student from Kyiv, quickly left Ukraine and went to Budapest, then Paris, where she is living with friends. - In France, she takes in-person classes in the morning and logs on in the afternoon to complete work for her Ukrainian school certificate.

- She's also been working on her presentation for ISEF. Her scientific interest is organic chemistry and how it can be leveraged to improve anti-cancer drugs. She developed analogs of a drug that are soluble in water instead of a sugar solution, making them a possible cancer treatment for people with diabetes.

Her biggest challenge: Her supervisor and mentor was living under occupation in Kyiv. It was difficult to communicate with her, but Smovzh said she messaged Smovzh when she could and helped her despite the circumstances. - "She's very courageous," Smovzh says.

Sofiia Timofieieva, a 10th grade student from Dnipro, is now living with her aunt and extended family in Frankfurt, Germany, and preparing for ISEF. - For her project, she created a type of solid disinfectant that doesn't use antibiotics and could be used to bandage wounds.

What they're saying: The students "reflect Ukraine's strength in science and engineering on the world stage; their resilience and bravery to pursue excellent scientific work while facing military attack is nothing short of inspiring," says Maya Ajmera, president and CEO of the Society for Science, which organizes ISEF and publishes Science News. What's next: Smovzh says without hesitation that she wants to return to Ukraine to attend university. Since that isn't likely to happen next year and she doesn't want to miss a year of school, she's beginning to look at universities in other countries. |     | | | | | | A message from PhRMA | | Insured Americans face barriers to care | | |  | | | | Nearly half of insured Americans who take prescription medicines encounter barriers that delay or limit their access to medicines. Learn more about the abusive insurance practices that can stand between patients and the care they need in PhRMA's new report. | | | | | | 4. Worthy of your time | | The gene-edited pig heart given to a dying patient was infected with a pig virus (Antonio Regalado — MIT Tech Review) Long-awaited accelerator ready to explore origins of elements (Davide Castelvecchi — Nature) What happens to the gut microbiome after taking antibiotics (Sophie Fessl — The Scientist) Ancient zircons may record the dawn of plate tectonics (Nikk Ogasa — Science News) |     | | | | | | 5. Something wondrous |  | | | Field site on the Whillans Ice Stream, West Antarctica. Credit: Kerry Key, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University | | | | Deep under the ice in West Antarctica, a massive reservoir of groundwater may help to drive ice from the interior of the continent to the ocean, scientists report today. Why it matters: Determining how fast-flowing streams of ice work would allow researchers to better understand how ice melt in Antarctica contributes to sea level rise. - Right now, projections for sea level rise don't include the contributions from the groundwater reservoir to the timing, size and pace of ice streams.

Background: Scientists knew there is shallow water that moves through a network of channels, lakes and porous sediments just under the ice streams. - But for decades, they suspected there was also water deeper under the ice, much like aquifers on other continents.

What's new: Measurements of seismic activity and the electromagnetic fields around the Whillans Ice Stream in West Antarctica indicate there is a layer of sediment one half-mile thick that holds water like a sponge, Chloe Gustafson, a geophysicist at the University of California, San Diego, and a team of researchers report in the journal Science today. - They estimate it contains 10 times more water than the shallower sources.

- It is also saltier toward the sediment and becomes less salty toward the base of the ice.

- That suggests the groundwater is being exchanged with fresh water in the subglacial lakes above it, possibly providing those lakes with carbon that supports the life observed there, Wired's Gregory Barber writes.

The big picture: "Ice streams transport about 90% of Antarctic ice from the interior out to edges," Gustafson says. - "I would bet there is groundwater beneath all the ice streams, and it is a continental wide process that we haven't truly accounted for."

|     | | | | | | A message from PhRMA | | Voters want Congress to address health insurance | | |  | | | | A decisive majority of Americans (86%) agree Congress should crack down on abusive health insurance practices impacting patients' access to care. Why it's important: Greater transparency and accountability within the current health insurance system. Read more in new poll. | | | | Big thanks (and welcome) to Natalie Peeples on the Axios Visuals team, to Laurin Whitney-Gottbrath and Andrew Freedman for edits and to Carolyn DiPaolo for copy-editing this week's newsletter. |  | It's called Smart Brevity®. Over 200 orgs use it — in a tool called Axios HQ — to drive productivity with clearer workplace communications. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters. If you're interested in advertising, learn more here.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1300, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment