| | | | | | | | | | | Axios Science | | By Alison Snyder · Apr 07, 2022 | | Thanks for reading Axios Science. This week's newsletter is 1,676 words, a 6.5-minute read. - Send your feedback and ideas to me at alison@axios.com.

- 🌴 Programming note: We'll be off next week for spring break.

- Sign up here to receive this newsletter.

| | | | | | 1 big thing: Polar science threatens to crack under strain of war |  | | | Illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios | | | | Crucial scientific projects in the Arctic are in limbo — and their progress is under threat — as Russia becomes more isolated from the world for its invasion of Ukraine, my Axios colleague Andrew Freedman and I write. Why it matters: These research collaborations provide key insights about the effects of climate change, the health of the oceans and geology — and they underpin cooperation among the U.S., Russia and others in the geopolitical hotspots of the Arctic and Antarctica. Driving the news: Scientific projects and collaborations are on hold around the world as sanctions and the severing of ties with Russian research institutions prevent scientists in the U.S., Europe and elsewhere from working with their colleagues and students in Russia. - The war's effects are being felt acutely by scientists who work in the Arctic, where the summer research season is about to get underway.

- Last week's Arctic Observing Summit of international scientists monitoring how climate change is affecting the Arctic was closed to researchers from Russian institutions and organizations, Hakai reports.

- Last month, seven of the eight members of the Arctic Council, whose purview includes research cooperation around sustainable development and environmental protection of the Arctic, paused all activities with Russia, the council's eighth member and current chair.

Details: About 53% of the Arctic Ocean coastline belongs to Russia. Access alone to that land and sea makes the country a key partner for international research on biology, ecology and conservation. - The country is also home to the majority of Arctic permafrost, and in recent years, concerns have grown over the pace and extent of melting and an uptick in Siberian wildfires.

- Pressing projects to understand Arctic fires, conducted under the Arctic Council's auspices, are in a state of suspended animation.

Yes, but: While the impacts of lost research opportunities will build up over time, a months long pause likely won't be especially damaging, according to Malte Humpert, senior fellow and founder of the nonprofit Arctic Institute. - "A 'pause' of a few weeks or a few months is one thing, but how will this work be organized and continued if the [Arctic Council] remains defunct for years?" he says.

On the other end of Earth, Antarctica is dominated by science activities. - It's too soon to determine the war's effects on research on the continent as it is heading into winter and reduced operations, says Alan Hemmings, a polar specialist and adjunct professor at the Gateway Antarctica Centre for Antarctic Studies & Research at the University of Canterbury in Christchurch, New Zealand.

- He adds that large international science programs on Antarctica could continue much like the ISS.

The big picture: China, India and other countries are keeping — and in some cases moving forward with plans to strengthen — their scientific ties to Russia, Nature reported this week. What to watch: Existing projects are being stressed, but the war could already be shaping the future of polar science. - A spokesperson from the National Science Foundation, which leads most U.S. research in the Arctic, urged researchers "to consider whether this is the best time" to conduct projects in Russia or with scientists from Russian institutions or whether their "research objectives can be accomplished through other means."

|     | | | | | | 2. Catch up on COVID |  Data: N.Y. Times; Cartogram: Kavya Beheraj/Axios - COVID case numbers are rising again in half of U.S. states while nationwide totals continue to fall, Axios' Tina Reed and Kavya Beheraj write.

- "Even people who have had COVID-19 receive long-lasting benefits from a full course of vaccination, according to three recent studies," Saima May Sidik reports for Nature.

- FDA advisers began "sketching out a long-term strategy for COVID vaccinations, addressing the risk of new variants and the need for new boosters," Axios' Adriel Bettelheim writes.

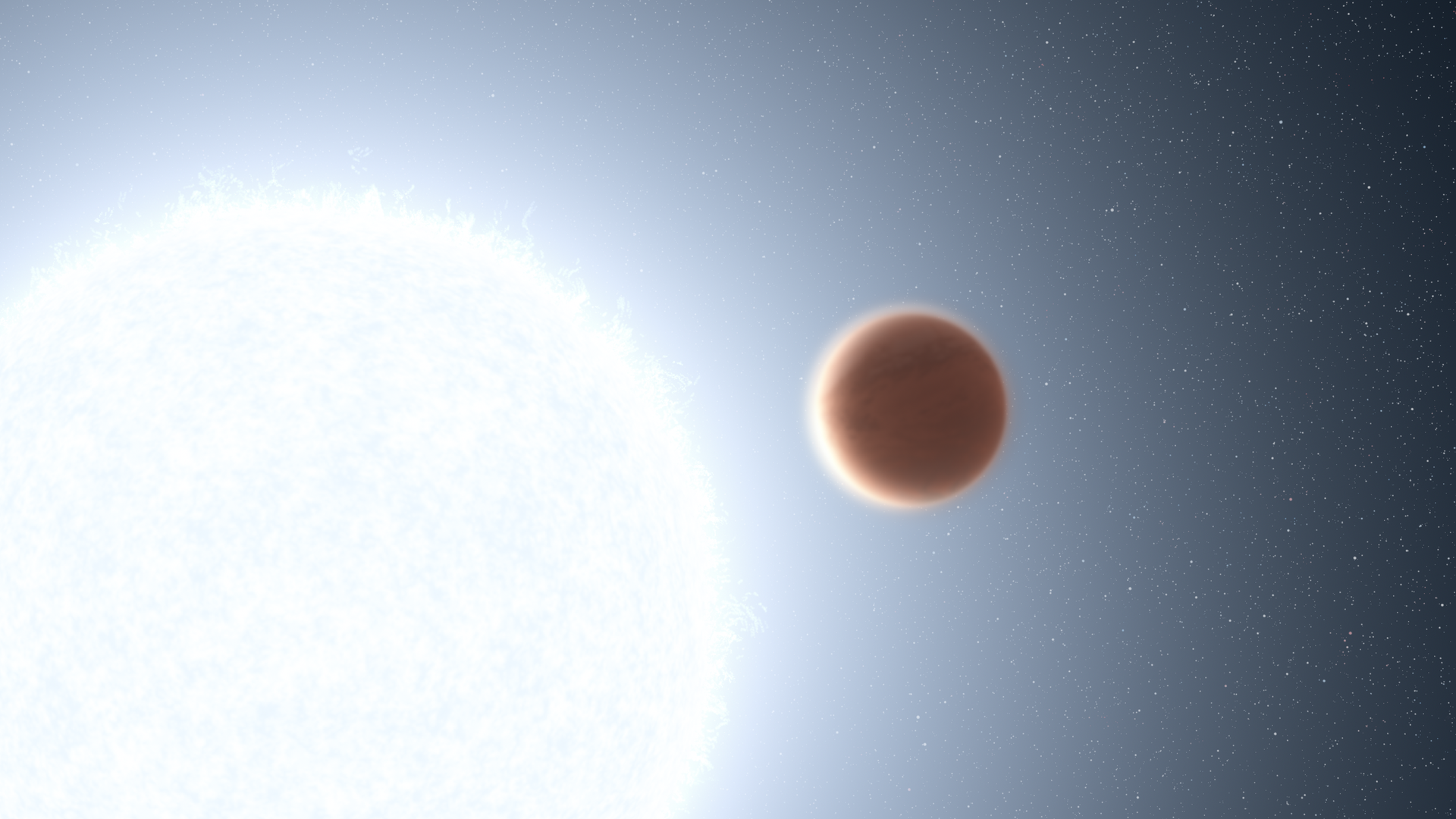

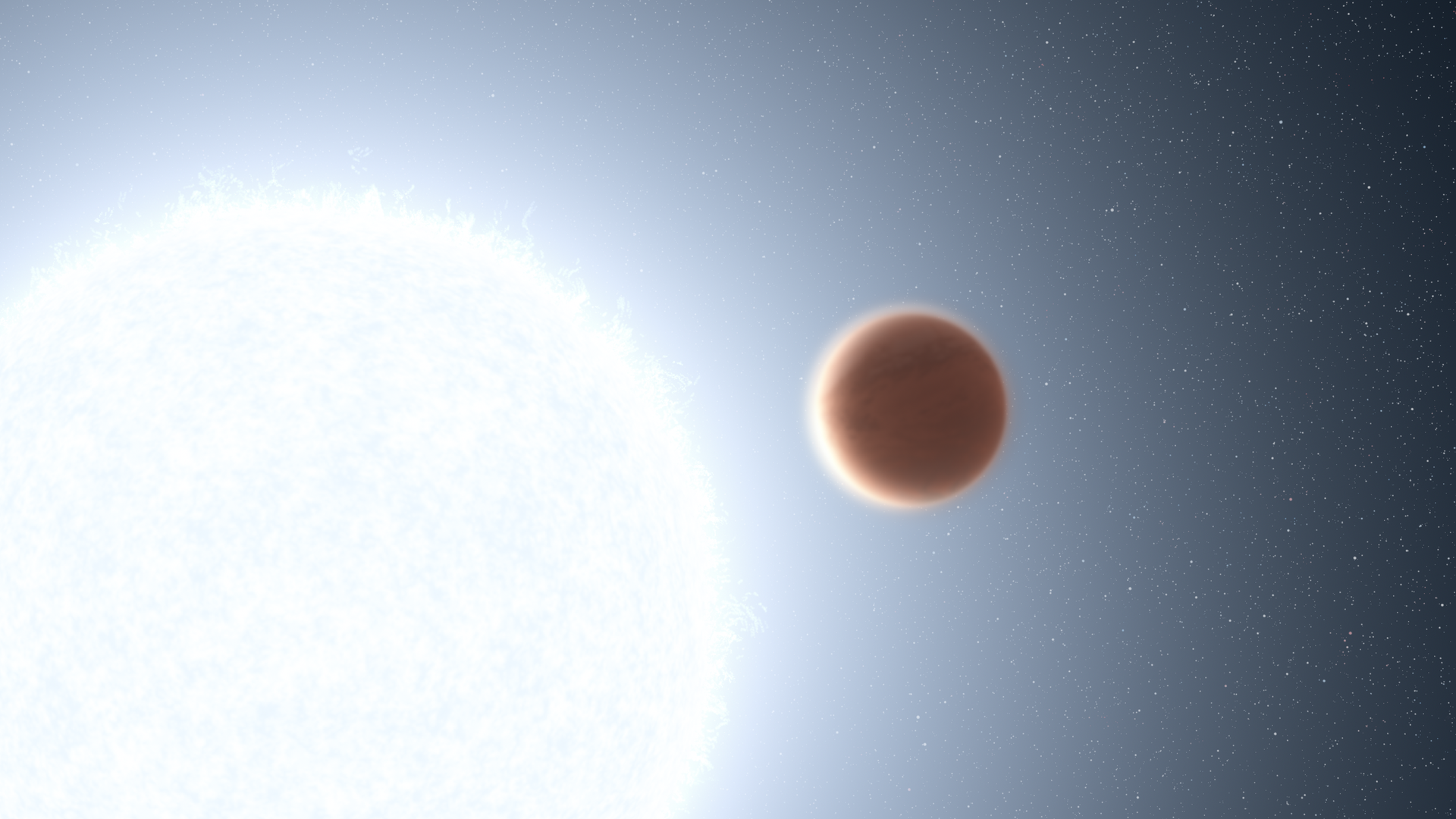

|     | | | | | | 3. Hubble peeks at "ultra-hot" Jupiter-like planets |  | | | An artist's depiction of an ultra-hot gas planet, KELT-20 b. Illustration: NASA, ESA, Leah Hustak | | | | Astronomers studying massive, extremely hot Jupiter-like exoplanets have found evidence of extreme weather conditions — like raining vaporized rock — and atmospheric chemistry occurring on the worlds, NASA announced yesterday. Why it matters: Studying the exotic weather on these uninhabitable gas giants can help researchers better understand Earth's atmosphere and the atmospheres of other potentially inhabitable terrestrial planets, Axios' Jacob Knutson writes. On WASP-178 b, a gas giant discovered in 2019 around 1,300 light-years away from Earth, Hubble Space Telescope researchers detected the presence of silicon monoxide, suggesting the solid is condensing and raining from clouds in certain parts of the planet. On KELT-20 b, another extremely hot gas giant discovered in 2017 about 400 light-years away, researchers discovered a thermal inversion layer in its atmosphere — similar to Earth's stratosphere — caused by ultraviolet light from its parent star heating atmospheric metals to extremely high temperatures. - This inversion layer creates KELT-20 b's unique atmosphere, which seems to contain more water and carbon monoxide than other hot Jupiter-like planets, as detailed in a paper published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters in January.

|     | | | | | | A message from Axios | | Get smarter, faster on the internet's native currency | | |  | | | | Axios Crypto brings you daily updates on the most consequential trends in cryptocurrency and the blockchain Why it matters: Cryptocurrencies are moving into the mainstream, upending financial markets, and creating new ways to monetize the internet. Subscribe for free | | | | | | 4. International STEM graduates stick around |  Data: National Science Foundation; Analysis: Center for Security and Emerging Technology; Chart: Baidi Wang/Axios Most international students who received doctoral degrees in science, technology, engineering and math from U.S. universities between 2000 and 2015 remain in the country long after graduating, according to a new analysis. Why it matters: The data suggests concerns about many U.S.-trained researchers returning to their home countries with skills and knowledge that could pose national security risks to the U.S. are "largely unfounded," researchers at Georgetown University's Center for Security and Emerging Technology write. - "If anything, available data supports the Chinese Communist Party's concern that China is losing STEM talent to the United States and other countries," the brief says.

Details: The researchers found about 77% of the roughly 178,000 international students who received a STEM PhD between 2000 and 2015 were still in the U.S. as of early 2017, according to survey data from the National Science Foundation. - 90% of the 55,000 graduates from China and 87% of the 28,000 from India during that time remained in the U.S.

- Together, they make up about half of all international graduates who stay.

Yes, but: China, for example, has adapted its own research programs so scientists based outside China can hold positions and work in both the U.S. and China. These arrangements were one focus of the U.S. Department of Justice's China Initiative, which was ended in February after accusations of racial profiling. Keep in mind: The analysis only looks at PhD graduates, not those with master's and bachelor's degrees who are also part of the STEM talent pool. The big picture: There's ongoing debate about how open the U.S. scientific system should be to international talent and collaboration because of concerns about a "reverse brain drain" increasing the risk of research theft. - But the new data doesn't support the notion that many PhD students leave, says Jack Corrigan, a co-author of the brief and research analyst at CSET.

- "That is not to say research security is not a concern," he says. "We still need to be wary of specific ties, but to all countries. Blanket policies that target people from a single country will probably do more harm than good."

|     | | | | | | 5. Worthy of your time |  | | | Illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios | | | | The search for next-generation cancer treatments (Caitlin Owens and me — Axios AM Deep Dive) Can mushrooms "talk" to each other? (Natalia Mesa — The Scientist) The web of life (Juli Berwald — Aeon) We're children of ice and snow. Can we survive the coming heat? (Robert Frodeman and Mark Bullock — Psyche) |     | | | | | | 6. Something wondrous |  | | | Images generated by DALL-E 2 in response to the prompt "astronaut riding a horse." Credit: OpenAI | | | | A new algorithm can produce realistic images from a text prompt, OpenAI announced this week. The big picture: As advancements in artificial intelligence surge forward, projects like DALL-E 2 could help researchers to create systems that visualize the world around them. - "The world is not just text," says OpenAI co-founder and chief scientist Ilya Sutskever. To gain a more human-like understanding of the world and to interact with people, "our neural networks need to master the visual world."

How it works: OpenAI's text generator GPT-3 builds on a prompt to predict what word would most likely come next in a sequence. - The image generating algorithm DALL-E 2 works in the same way but its palette is pixels not words.

- It uses a language model called CLIP to first take a text prompt and try to produce dots with features that represent the prompt.

- Then it uses a neural network to render an image that tries to match the text provided.

In a demo with me this week, researchers showed off a range of images DALL-E 2 can generate — from "teddy bears mixing sparkling chemicals as mad scientists" to "an ibis in the wild painted in the style of John Audubon." - The algorithm builds on earlier work, but generates higher resolution images and adds the ability to make specific edits to parts of an image and to generate variations of an image from the same prompt.

- "It's really fascinating," says OpenAI research scientist Prafulla Dhariwal. "It's like watching art being generated through math, and it is kind of magical."

But, but, but ... DALL-E 2 does make mistakes. - It struggles when asked to count large numbers of features — for example, if you ask it to draw a cat with eight legs.

- And it has a hard time when prompted to go against strongly held priors established through training — like a big mouse chasing a small lion.

What to watch: Like the language generator GPT-3, there are concerns about its misuse. - The OpenAI researchers say they are taking steps to try to minimize the risk, including removing violent content from the algorithm's training data, filtering violent or pornographic prompts, and having humans review the images shared on the platform. (Images will also have a signature — the rainbow in the bottom right corner.)

So is it considered creative? It depends what you mean and who you ask. - The AI has the ability to create variations of images by breaking them down into their essential components and then blending them together, says OpenAI researcher Aditya Ramesh.

- "To the extent that humans can take an idea from a source of inspiration and apply it to something new, this can be viewed as a kind of creative ability."

|     | | | | | | A message from Axios | | Get smarter, faster on the internet's native currency | | |  | | | | Axios Crypto brings you daily updates on the most consequential trends in cryptocurrency and the blockchain Why it matters: Cryptocurrencies are moving into the mainstream, upending financial markets, and creating new ways to monetize the internet. Subscribe for free | | | | Big thanks this week to Sarah Grillo and Baidi Wang on the Axios Visuals team, to Jacob for contributing and to Carolyn DiPaolo for copy editing this edition. |  | It's called Smart Brevity®. Over 200 orgs use it — in a tool called Axios HQ — to drive productivity with clearer workplace communications. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters. If you're interested in advertising, learn more here.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1300, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment