| | | | | | | Presented By Malwarebytes Business Solutions | | | | Axios Science | | By Alison Snyder ·Oct 07, 2021 | | Thanks for reading Axios Science. This week's newsletter is 1,676 words, a 6-minute read. | | | | | | 1 big thing: What the science says about fertility and COVID vaccines |  | | | Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios | | | | A growing number of anecdotes about COVID-19 vaccines affecting a person's menstrual cycle is spurring attention and research funding, Axios' Eileen Drage O'Reilly writes. Why it matters: Efforts to halt the pandemic are being stymied by continued vaccine hesitancy, in part due to disinformation about side effects. A CDC scientist tells Axios "there is absolutely no evidence" that the altered periods reported by some are causing infertility, a common refrain among anti-vaxxers. - "Women of childbearing age should absolutely be vaccinated," says CDC medical officer Christine Olson, who is head of the v-safe pregnancy registry.

Threat level: Pregnant people who have a symptomatic COVID infection "have a twofold risk of admission into intensive care and a 70% increased risk of maternal death," particularly with the highly transmissible Delta variant, Olson says. What's happening: There are "thousands and thousands and thousands" who are reporting an impact from the COVID vaccine, particularly on menstruation, says Namandjé N. Bumpus, director of the department of pharmacology and molecular sciences at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. - However, Bumpus adds, "it remains to be seen if there's a causal link or not."

- Olson points out that the CDC "is aware of reports of menstrual irregularities" and continues studying the issue. NIH is funding five one-year supplementary grants worth $1.67 million to further investigate if there's a link and what the underlying mechanisms may be.

- One of the theories is that the change in a person's period could be caused by a temporary immune response to the vaccine, as the endometrium lining the uterus contains multiple immune cells, says Alice Lu-Culligan, an M.D.-Ph.D. student at Yale School of Medicine who is researching the topic and wrote an opinion piece in April.

Changes in menstrual cycles can be caused by many factors like stress or new medications, can happen frequently, and often are temporary without an impact on fertility, says Viki Male, a lecturer in reproductive immunology at Imperial College London. - "The concern about infertility is hypothetical. There is no current evidence to support this, and there are most certainly pregnancies occurring every day following COVID-19 vaccination," Olson says.

Between the lines: Multiple sources say the decision in the early clinical vaccine trials to exclude pregnant people fueled hesitancy. - "We should have known that we were going to need to vaccinate people who are pregnant, but we ended up without trial data from them. I think that's something we should also learn from in the future," Male says

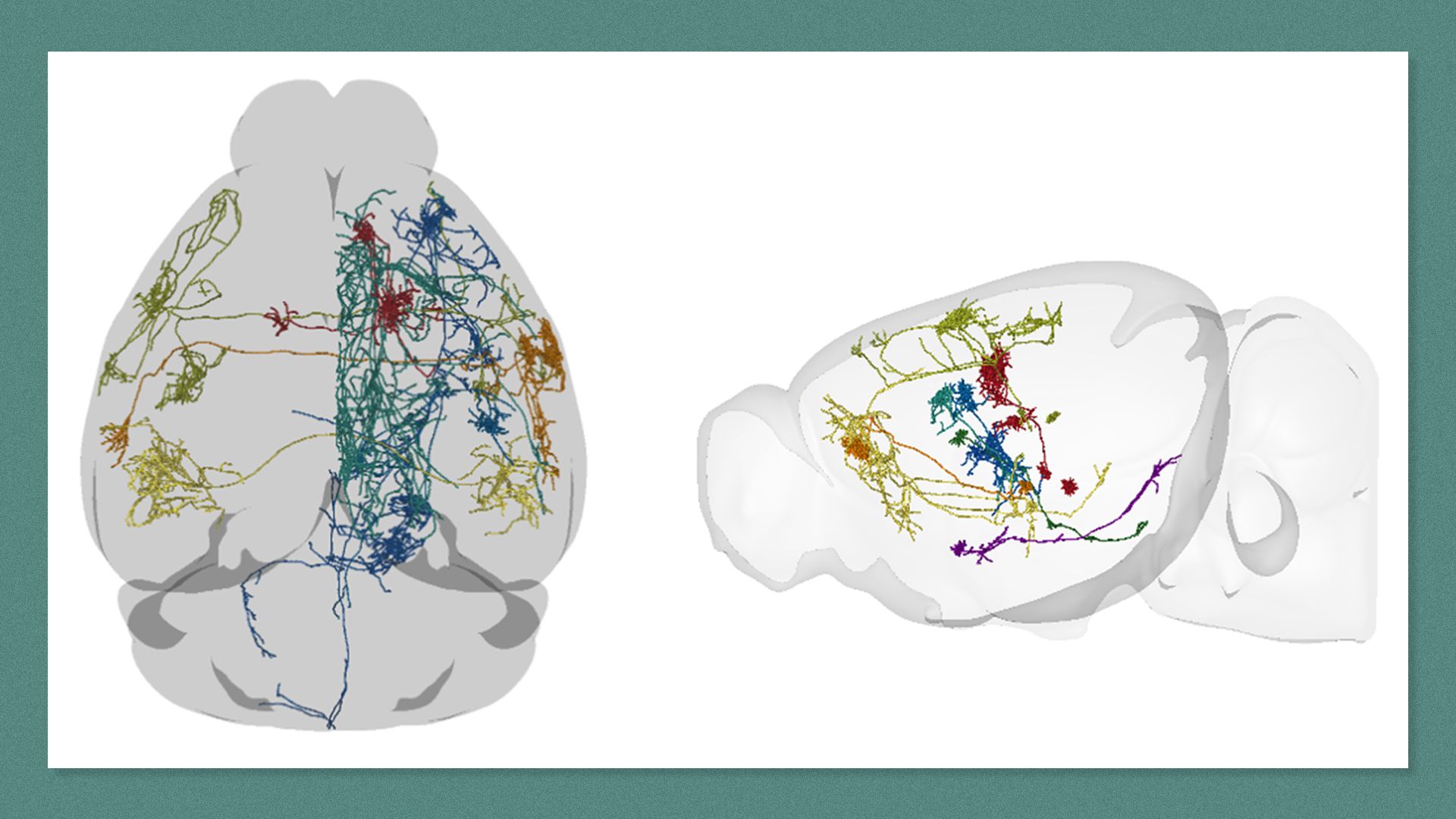

The bottom line: Vaccination is essential "for anyone wanting to make sure their pregnancy is the healthiest it can be and results in a healthy infant," Olson says. Sign up for Axios AM to receive our Deep Dive about women's health this Saturday. |     | | | | | | 2. Catch up on COVID-19 |  Data: N.Y. Times; Cartogram: Kavya Beheraj/Axios "The Delta wave may truly be behind us," Axios' Sam Baker writes. "COVID-19 cases have been falling across the U.S. for weeks — and now deaths are finally on the decline, too." Concerns about long COVID are fueling the Biden administration's push to expand vaccine boosters, the WSJ's Stephanie Armour and Felicia Schwartz report. Pfizer and BioNTech asked the FDA to authorize the use of their coronavirus vaccine in children between the ages of 5 and 11. "Anxiety and depression severity scores are one and a half to two times what they were in 2019," Axios Marisa Fernandez reports from new CDC data. |     | | | | | | 3. A census of brain cells |  | | | Reconstructions of several different types of mouse neurons showing their position in the mouse brain. Credit: Allen Institute | | | | Scientists have created a catalog of the cells in the brain's movement control center — a first step toward deciphering the circuits of the brain's nearly 90 billion neurons that underpin our movements, thoughts and emotions. Why it matters: Cells don't operate in isolation. Determining the circuits that connect neurons could help researchers understand processes in the brain and what happens when they go awry from disease. - Ultimately, the hope is these brain maps will provide new targets for drugs to treat Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases, as well as neuropsychiatric diseases where there is an aberration in the way cells communicate, says John Ngai, director of the NIH's BRAIN (Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies) Initiative, which coordinated the effort to create a cell census.

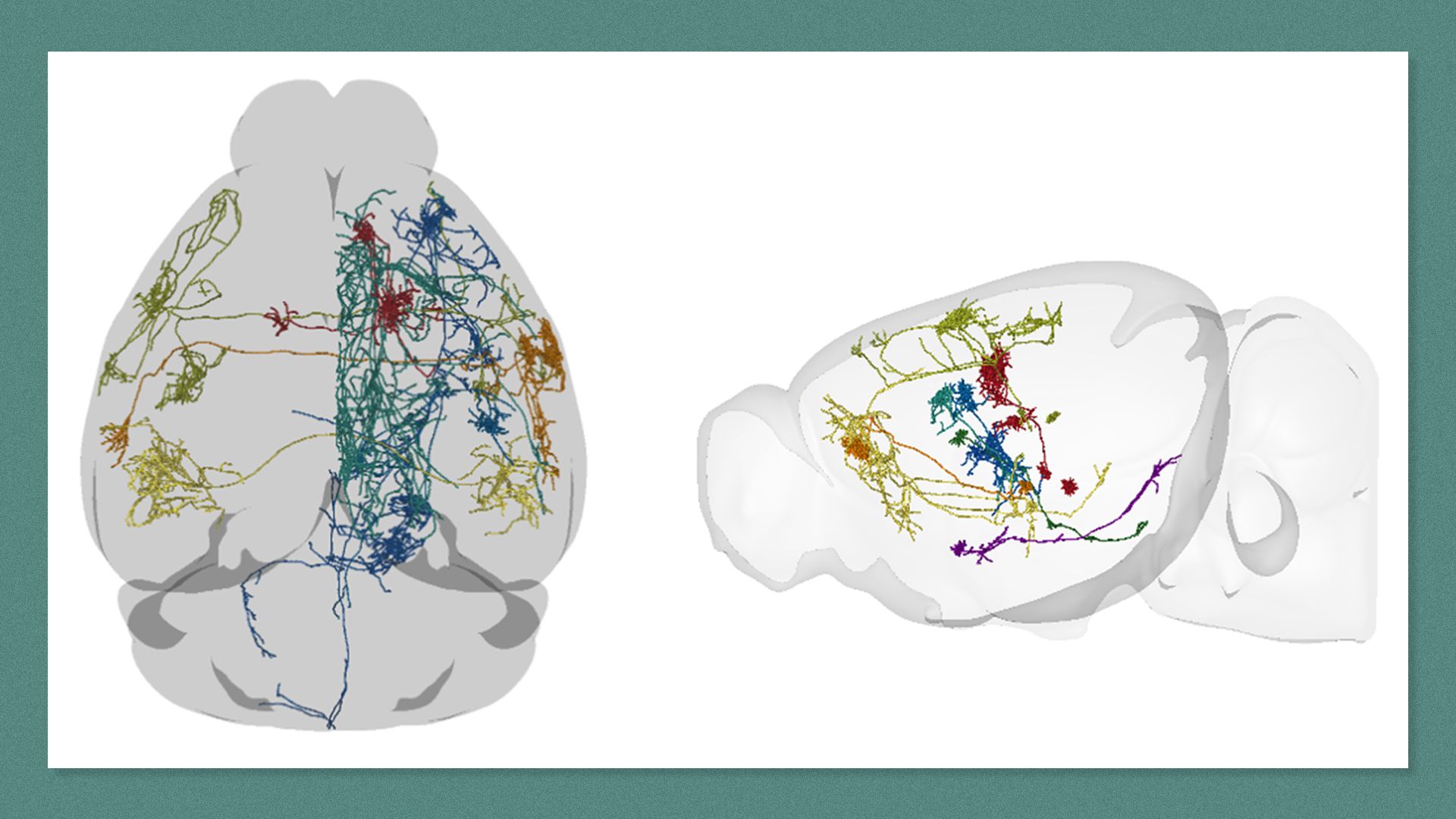

Driving the news: Hundreds of researchers collaborated to define and catalog the cells in the primary motor cortex region of the brains of mice, marmosets and humans, they report this week in 17 papers in the journal Nature. - The goal of the research is to generate a "parts list for the brain," says Hongkui Zeng, director of the Allen Institute for Brain Science and co-author of some of the papers.

- There are close to 170 billion cells in the brain (about half are neurons and half are other cells) with trillions of connections between them. Some cells can have similar shapes but differ in their functions and locations.

- Researchers have struggled to place cells into distinct groups, which would help them figure out the circuits they form and how they function.

What they did: The researchers combined information about the genes being expressed in cells (their transcriptome), their shape, electrical activity and other properties, and found more than 100 types of cells in the human motor cortex. - Comparing the RNA information with the shape, electrical activity and other properties of cells, the researchers found that RNA patterns can be used to predict a cell's type.

- They then determined where classes of cells were located within the motor cortex, which is involved in coordinating movement.

Yes, but: A map of the entire human brain circuitry is still far in the future. - "Getting a parts list is really only the first step," Zeng says. "We don't know what the cell types do yet and how they are connected with one another."

- There's also the issue of how cell circuits vary between individuals and how they change, whether subtly with time or dramatically during development or disease, she says.

- And there is the sheer size of the human brain: It is 200 times larger than a mouse brain. "It could take two years to do the whole mouse brain," Zeng says, adding there is a need for tools to speed the process. "We don't want to take 1,000 years to do the human brain."

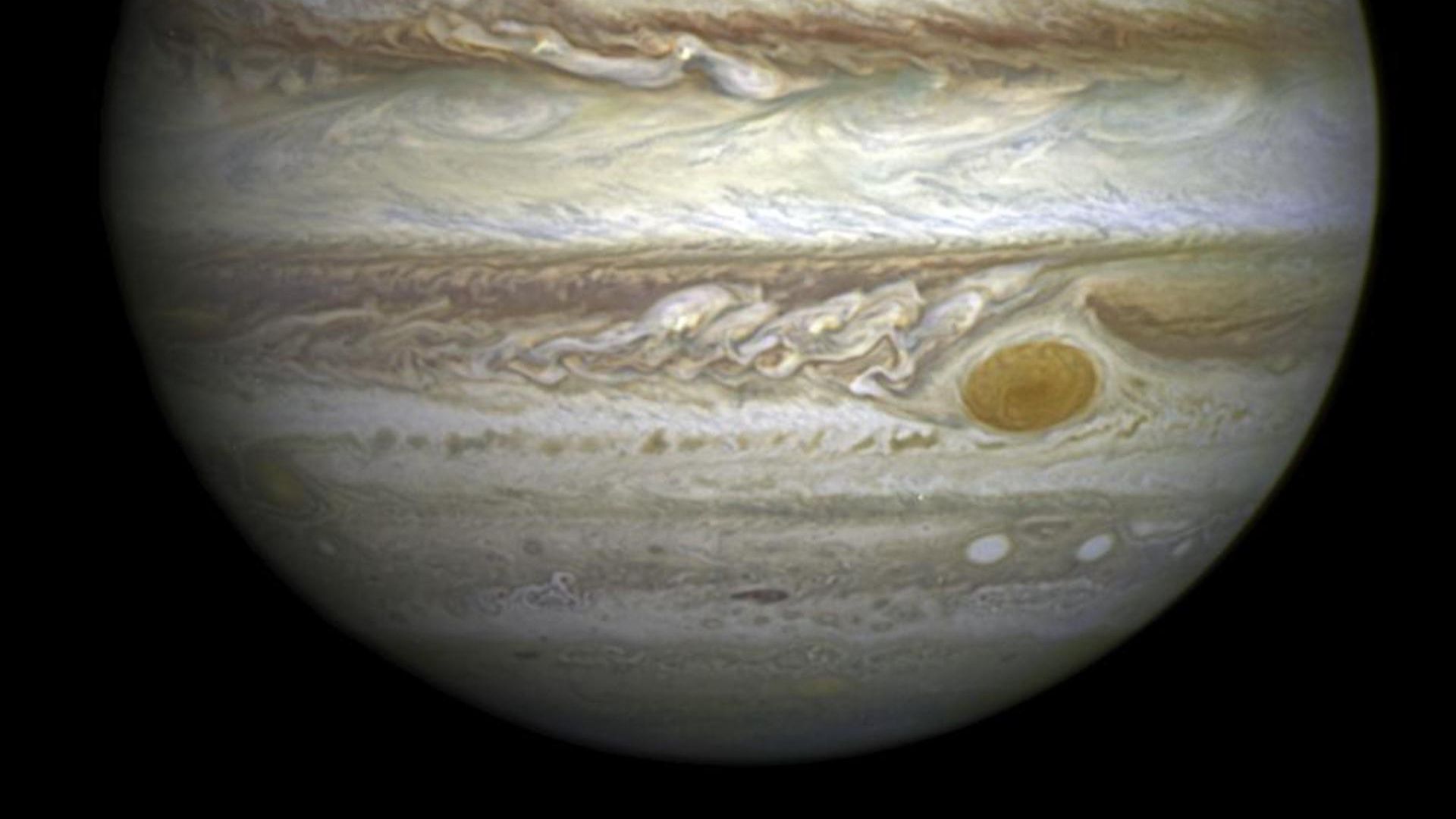

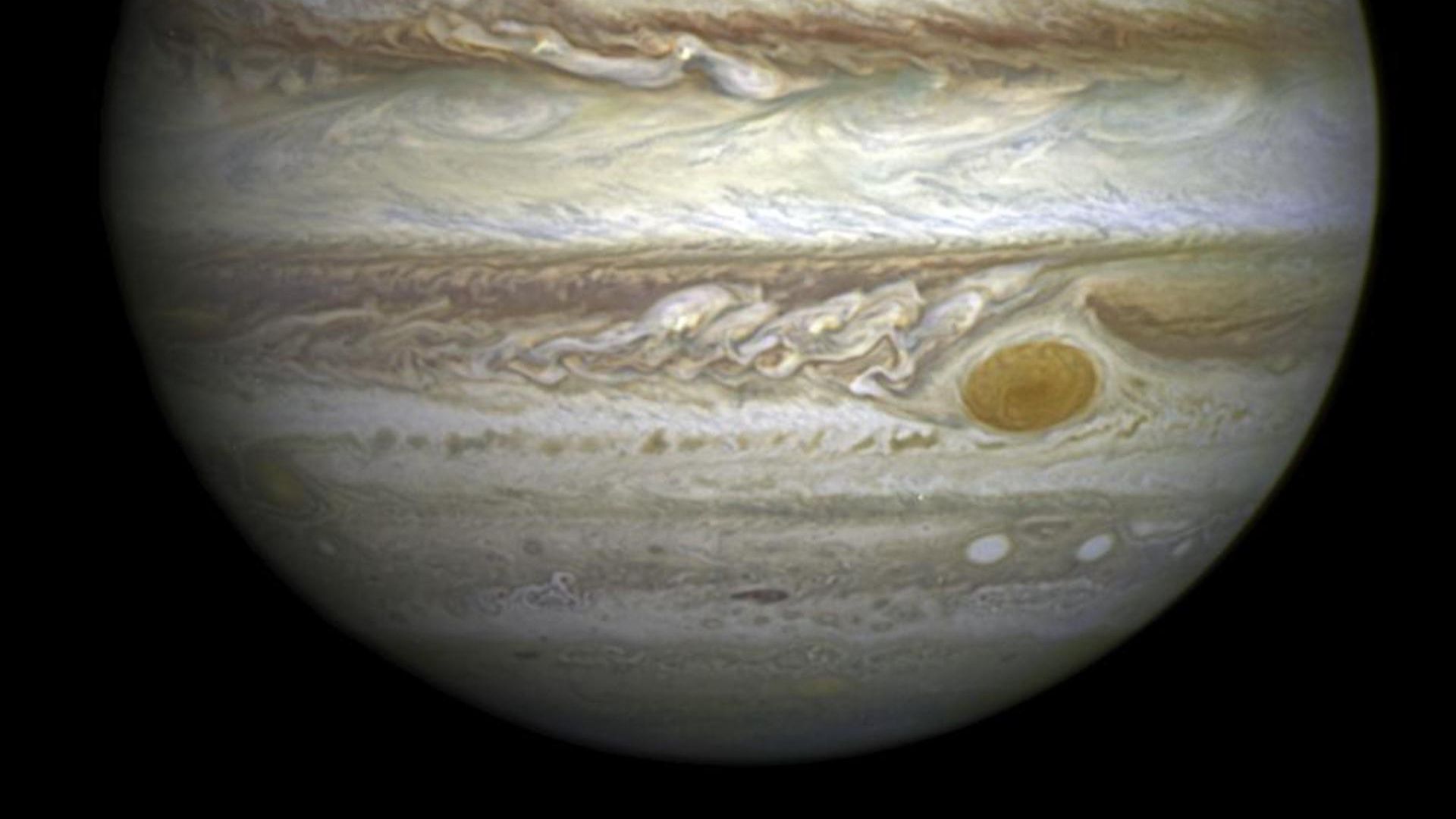

Read the entire story. |     | | | | | | A message from Malwarebytes Business Solutions | | Secure your business devices and data from cyberattacks today | | |  | | | | Malwarebytes Business Solutions' Back to Business Sale has been extended. There's never been a better time to level up your security stack with the top-rated, cloud-based solution. Get 25% off and try Endpoint Protection or Endpoint Detection and Response with 72-hour ransomware rollback. | | | | | | 4. The winds within Jupiter's Great Red Spot are gaining speed |  | | | Jupiter's Great Red Spot seen by the Hubble Space Telescope. Photo: NASA/ESA/STScI | | | | The winds of one of the most recognizable storms in the solar system — Jupiter's Great Red Spot — are speeding up, Axios' Miriam Kramer writes. Why it matters: This weather report for another world is possible because the Hubble Space Telescope has been keeping a close eye on the storm for more than 10 years. What's happening: Scientists using the Hubble have found the winds just inside the bounds of the spot have "increased by up to 8 percent from 2009 to 2020," according to NASA. - Wind speeds in the inner area of the storm have slowed down in that time period.

- The researchers behind the new study aren't sure what's causing that change in wind speed seen over time, but it may have something to do with changes below the planet's cloud tops out of view of the Hubble.

The big picture: The Great Red Spot has been seen by people on Earth for 150 years, and this isn't the first time scientists have spotted changes in the huge storm. - Over the years, researchers have also found the storm is shrinking and changing its shape from oval to circular.

|     | | | | | | 5. The Nobel's persistent diversity problem |  Data: Nobel Prize; Note: Data does not include 2021 economics prize to be announced on Oct. 11; "Other" includes 7 countries with one winner each and 6 winners from multiple countries; Chart: Kavya Beheraj/Axios This year's Nobel Prizes in physiology or medicine, physics and chemistry all went to men. The big picture: A lack of diversity persists among those awarded science's top prize. - 25 of 387 Nobel Prizes awarded in science and economics have gone to women in the history of the prize. (Axios first published this chart four years ago.)

- W. Arthur Lewis, who won the prize in economics in 1979, remains the only Black recipient in the sciences or economics.

Between the lines: "This is a problem much larger than simply bias on the part of the Nobel selection committees — it's systemic," chemist Marc Zimmer wrote last year. Go deeper: Hard Truths: Race and science in America (Axios) |     | | | | | | 6. Worthy of your time | | Public motivation for flu shot remains stale (Marisa Fernandez — Axios) Surrogacy across species (Chloe Williams — Hakai) Ozone pollution's threat to biodiversity (Jim Robbins — Yale360) Woman successfully treated for depression with electrical brain implant (Hannah Devlin — The Guardian) |     | | | | | | 7. Something wondrous |  | | | Aerial view of red mangrove forests along San Pedro Mártir River in Mexico. Photo: Octavio Aburto, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UC San Diego | | | | More than 120,000 years ago, a red mangrove forest was trapped far from the comforts of the salty waters of the Gulf of Mexico, a new study reports. The "lost world" is thriving along a river in the Yucatan Peninsula today. Why it matters: The ancient ecosystem reveals how past climate change shaped the world's coastline — and "opens opportunities to better understand future scenarios of relative sea level rise," the authors write. What they did: Octavio Aburto-Oropeza, a marine ecologist at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego, and his colleagues analyzed the genetics of the red mangroves (Rhizophora mangle) in the forest along the San Pedro Mártir River in Mexico and found they migrated from the coast to the river more than 100,000 years ago. - They also identified other species of flowering plants in the area that typically live near the ocean.

- Marine fossils and models suggesting sea levels during the last interglacial period were 20 to 30 feet higher than they are today indicate the area contained seawater during that time.

- The authors say that when the ocean waters receded in the last glaciation, the forest persisted in the freshwater that took its place.

- They think that is because limestone rocks deposit calcium carbonate in the water, which the mangroves can use to survive.

The backstory: "I used to fish here and play on these mangroves as a kid, but we never knew precisely how they got there," Carlos Burelo, a botanist at the Universidad Juárez Autónoma de Tabasco and co-author of the paper, said in a press release. - "That was the driving question that brought the team together."

|     | | | | | | A message from Malwarebytes Business Solutions | | Secure your business devices and data from cyberattacks today | | |  | | | | Malwarebytes Business Solutions' Back to Business Sale has been extended. There's never been a better time to level up your security stack with the top-rated, cloud-based solution. Get 25% off and try Endpoint Protection or Endpoint Detection and Response with 72-hour ransomware rollback. | | | | Thanks to Kavya Beheraj and Aïda Amer for this week's visuals and to Sheryl Miller for copy editing this newsletter. |  | | It'll help you deliver employee communications more effectively. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters. If you're interested in advertising, learn more here.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1300, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment