| | | | | | | Presented By Abbott | | | | Axios Science | | By Alison Snyder ·Sep 30, 2021 | | Thanks for reading Axios Science. This week's newsletter is 1,543 words, a 6-minute read. | | | | | | 1 big thing: Science of psychedelic therapy breaks on through |  | | | Illustration: Annelise Capossela/Axios | | | | Scientific studies of psychedelic therapies may be entering a new, broader phase thanks to more interest and funding from federal governments. Why it matters: MDMA, psilocybin and LSD — combined with psychotherapy — have shown promise for treating a range of addictions and mental health disorders, including treatment-resistant depression and PTSD. - Mental health and substance use disorders take lives and cost money — directly for treating the disorders and indirectly in productivity. Efforts to find new treatments have come up short, leading to a decline in investment in developing new drugs.

- The big dollars that come with funding from science agencies like the National Institutes of Health could allow researchers to study nitty-gritty details — about dosing and other variables — needed for a drug to become an accepted part of medical practice.

- Public funding could also allow trials of psychedelic therapies to be larger and more diverse, as well as independently evaluated.

The long, strange trip: The therapeutic benefits of psilocybin and LSD were studied in the 1950s and 1960s. - But that research largely stopped in 1970 for a combination of reasons, including concerns about recreational use of the drugs that led to them being classified as Schedule I compounds — which are considered to have no currently accepted medical use and carry a high risk for abuse. That hampered studies about their therapeutic use.

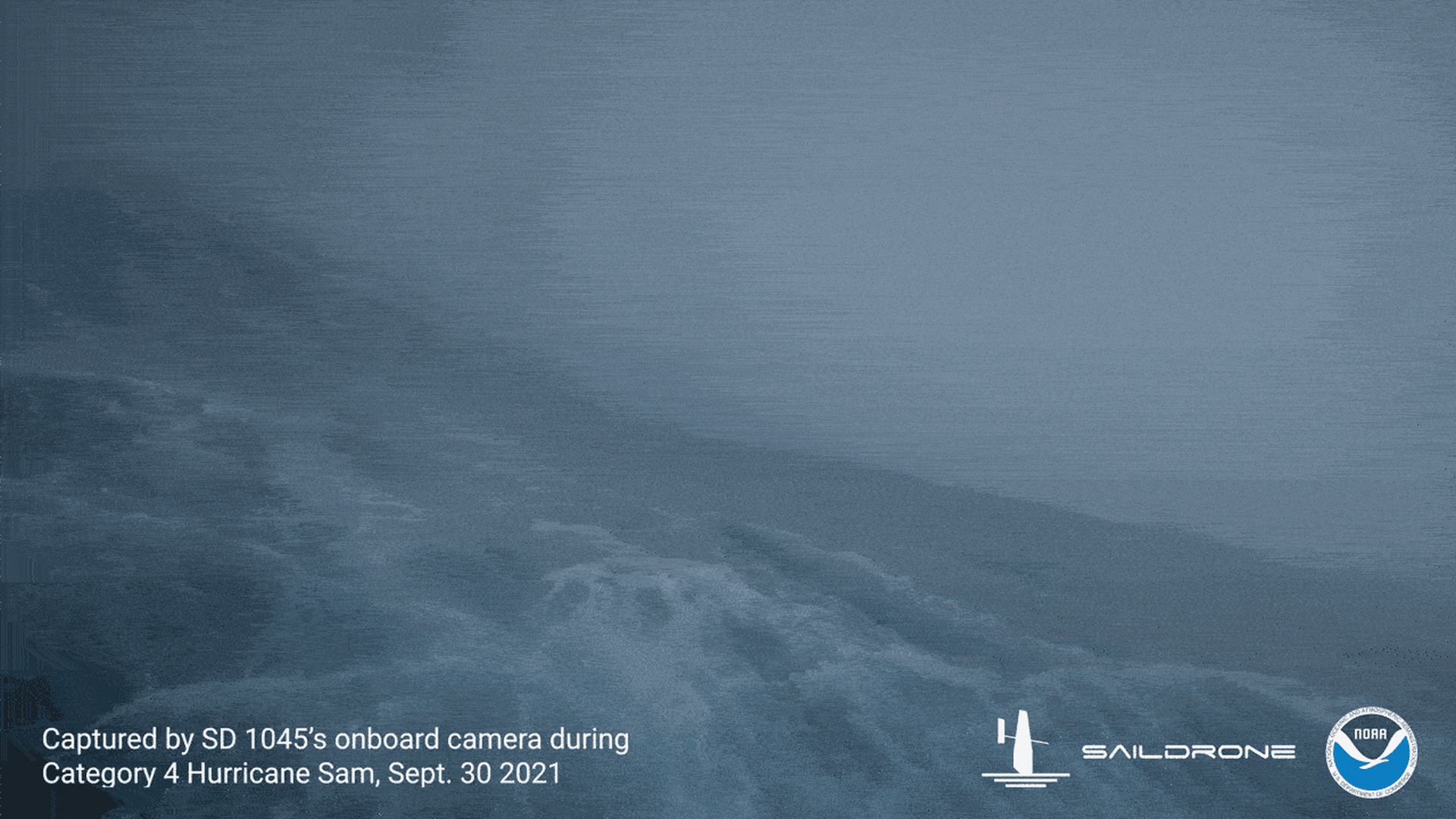

- About 20 years ago, there was a resurgence in studying psychedelics in humans, but the research has largely been backed by private philanthropists.

- That's partly because studies struggled to meet best scientific practices, like randomizing trials and having a placebo control, says Steven Grant, a former program officer at the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) who is now director of research at Heffter Research Institute, which promotes the scientific study of classic psychedelics, like psilocybin.

- There also weren't companies lining up to take the drugs and further develop them.

Where it stands: Philanthropists have funded pilot studies about psychedelic therapies, and a recent boom in biotech companies pursuing them indicates the treatments could have a path to market. - But in between foundational research and a treatment that can be prescribed, there's a need for more incremental science, which is often the purview of the NIH.

- The agency has funded research in psychedelics, but largely focused on the their potential for addiction, how they work and how they affect the brain.

- That informs whether and how they can be used in therapies but little federal funding has gone toward clinical studies in humans of treatments involving classic psychedelics like LSD and psilocybin. (NIH has supported research on the therapeutic effects of ketamine, which isn't considered a class psychedelic.)

|     | | | | | | 2. Part II: Psychedelic therapy science | | "The funding side of the government has been the last to the party for a long time," says Matthew Johnson, who studies psychedelics at Johns Hopkins University. What's happening: NIDA recently awarded Johnson a grant to investigate the use of psilocybin-enhanced therapy to help people quit smoking, building on earlier studies. The grant hasn't been added to the NIH's public database, but Johnson says it amounts to about $4 million. - It's a significant moment for the field, several psychedelic researchers told me.

- Funding from the NIH, which tends to award larger grants than philanthropists, allows researchers to delve more into the details, Johnson says. Studies can look at the effects of dosing, changing the type of therapy given and altering other variables that could optimize treatment.

"It is that type of non-sexy research that is the backbone for everything in the long term," he says. - The Australian government is also funding research into using psychedelics to treat mental disorders.

What they're saying: "Newly funded research on the therapeutic effects of hallucinogens reflects a resurgence in interest in hallucinogens in the scientific community and is predicated on the submission of well-designed research studies for funding consideration," NIDA director Nora Volkow told Axios in an email. Background: Earlier studies demonstrated psychedelics can be safely administered in combination with therapy and that treatment may alleviate depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder and substance use disorders. - The work also brought more scientific rigor to the field and showed how the effectiveness of psychedelic drugs can be measured, Grant says.

Yes, but: There are still challenges in evaluating the treatment, including the possibility of bias in participants who have expectations of the drugs. And the treatment is administered in highly controlled environments alongside repeated therapy sessions, a practical hurdle for widespread use. What to watch: Beyond the funding's impact on the science itself, knowing the NIH is open to investing in research about psychedelic therapies could spur more young researchers to enter the field, Johnson says. |     | | | | | | 3. Proteins give a clearer picture of cancer growth |  | | | Illustration: Rebecca Zisser/Axios | | | | A new analysis found unique networks of hundreds of proteins that may drive the growth of breast, head and neck cancers, according to three studies out today, Axios' Eileen Drage O'Reilly reports. Why it matters: Cancers differ in many aspects, including their mutations. But there are some common systems of cells involved, including protein networks, that may affect cancer growth, and scientists hope to target them with therapies. - By better understanding protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks and their role in driving cancers, scientists can greatly expand the number of potential drug targets.

The latest: The journal Science Thursday posted studies with an analysis that mapped 395 protein systems in 13 cancer types, focusing on data from studies on head and neck squamous cell cancers and breast cancers. - The three related papers examined how hundreds of mutations in breast and head and neck cancers affect the activity of proteins that drive the diseases.

- They also discovered some hard-t0-detect mutations in some proteins that may affect tumor growth as well as some biomarkers that could be used in clinical sequencing panels.

- For head and neck cancer, they found 771 PPIs, 84% of which were never reported before. The breast cancer findings include locating two proteins that affect the function of the tumor-suppressor gene BRCA1 and two proteins that regulate PIK3CA, which have been linked to breast cancer.

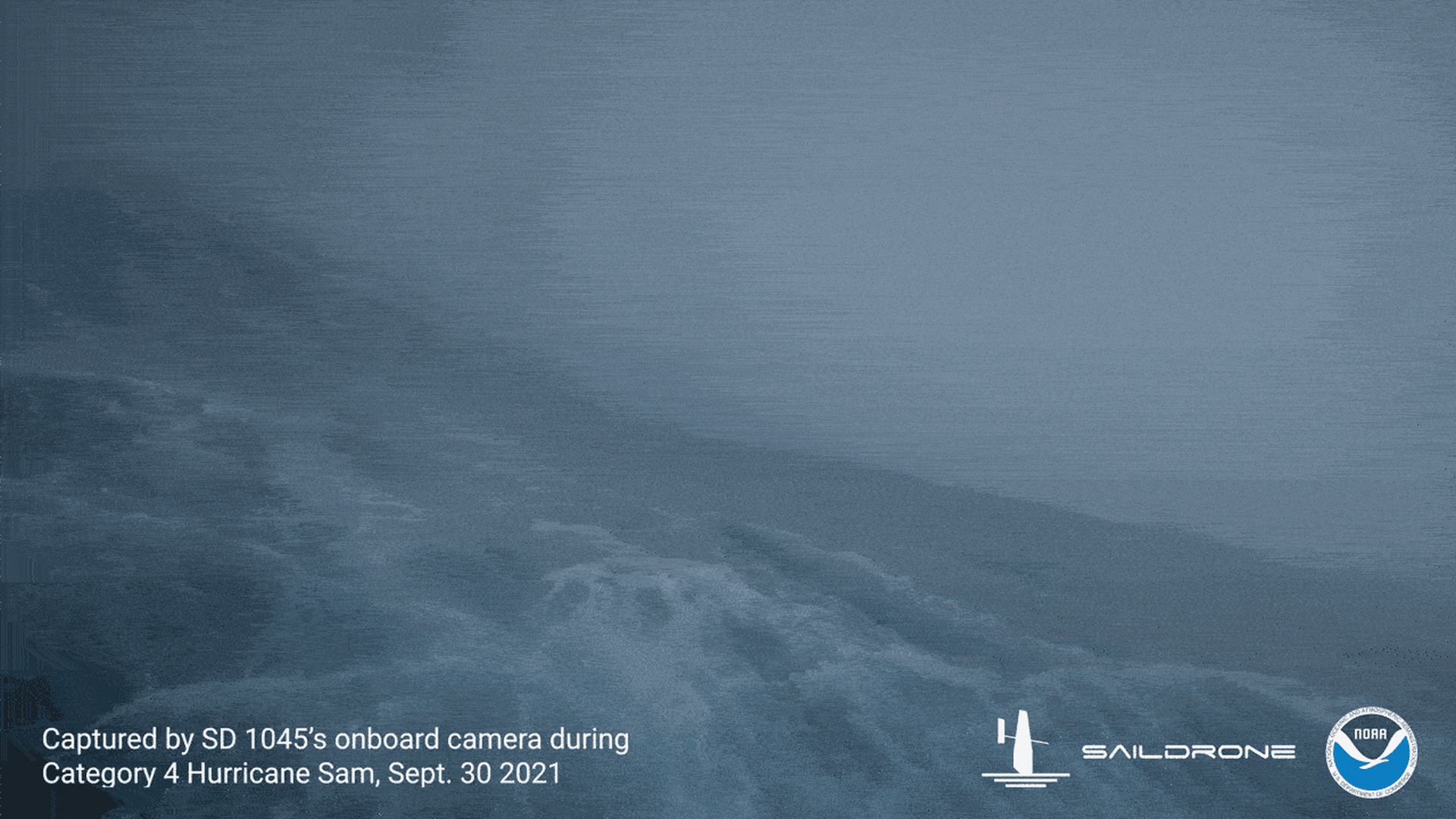

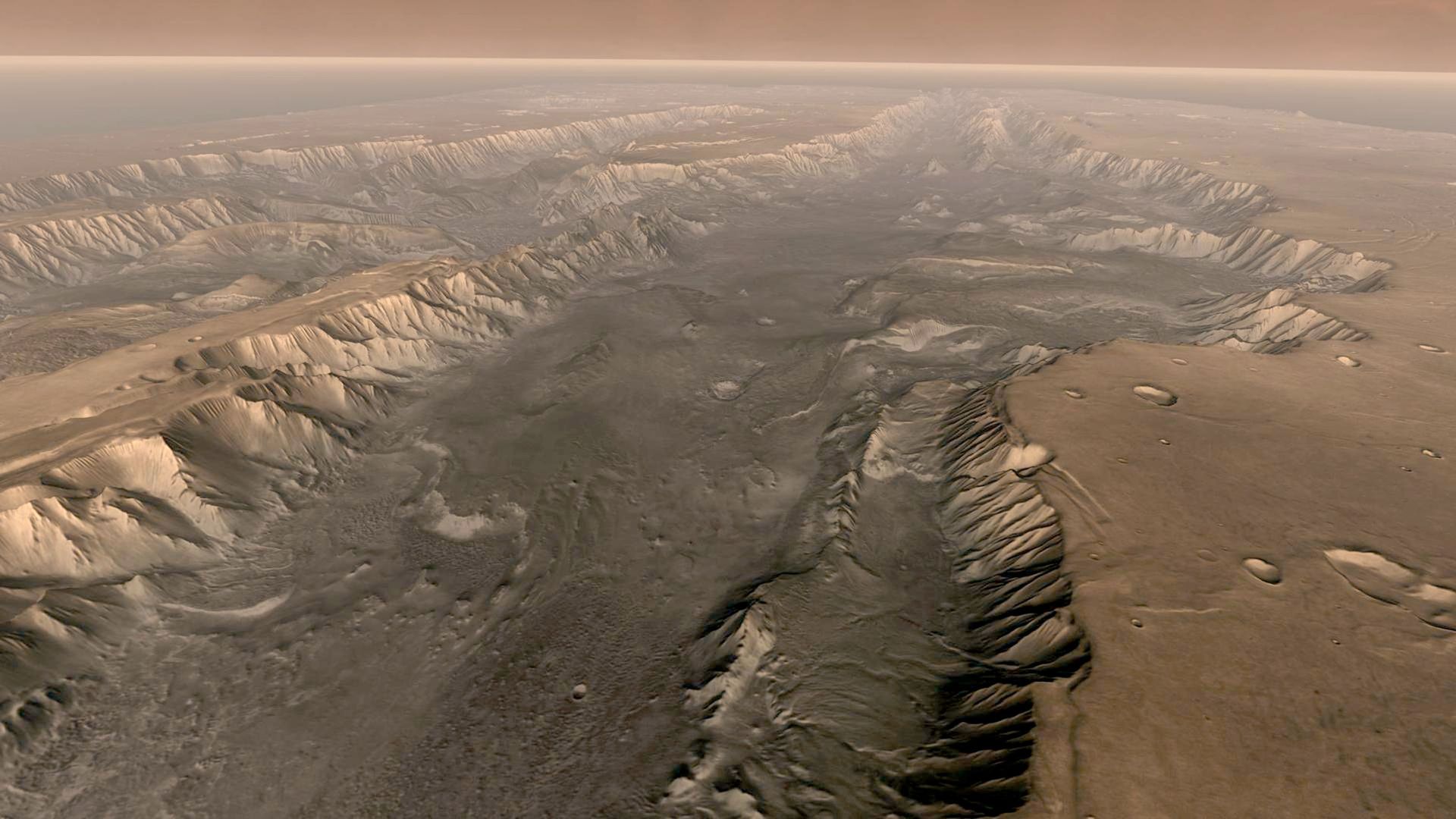

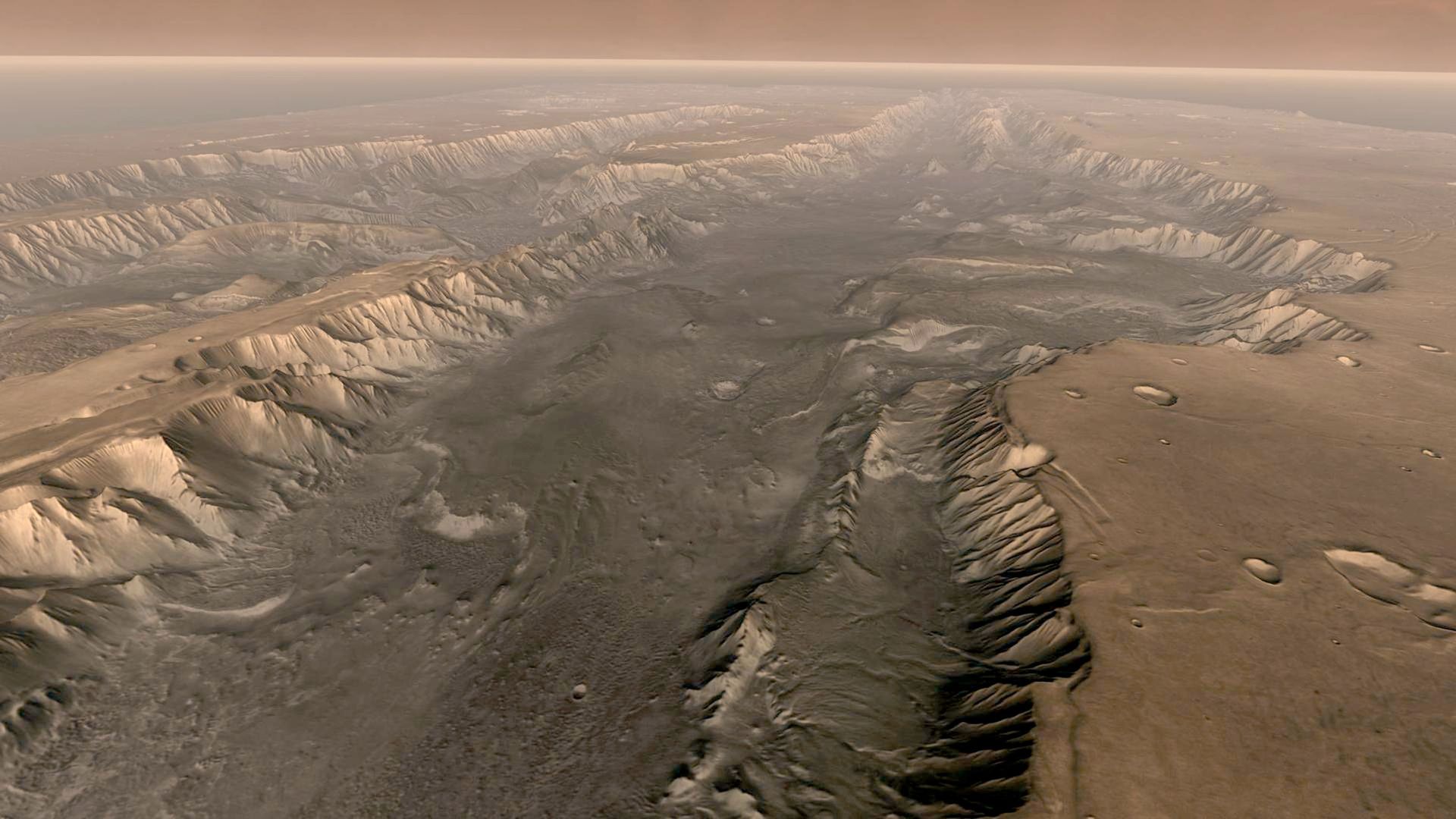

What's next: Researchers will continue working on the big question of which mutations in different genes affect the interactions of proteins that drive cancer growth, Marcus Kelly, postdoctoral researcher and a co-author of one of the papers, tells Axios. Go deeper. |     | | | | | | A message from Abbott | | COVID-19 Delta variant: What you need to know | | |  | | | | The Delta variant has come to dominate new coronavirus infections in the U.S. As we continue to gather at more public places and events at full capacity — including schools — here's what you need to know and how testing can help restore peace of mind. | | | | | | 4. Worthy of your time |  | | | From the video from the Atlantic Ocean inside Category 4 Hurricane Sam on Sept. 30, 2021. Credit: NOAA | | | | NOAA sailed a drone into Hurricane Sam, the strongest storm on Earth, and captured video (Andrew Freedman — Axios) U.S. declares more than 20 species extinct after exhaustive searches (Jacob Knutson — Axios) Hispanic Heritage: How a Colombian neurosurgeon saved our brains (Russell Contreras — Axios) Not every question has a scientific answer (Jay Varma — The Atlantic) |     | | | | | | 5. Catch up quick on COVID-19 |  Data: N.Y. Times; Chart: Kavya Beheraj/Axios "New coronavirus infections in the U.S. fell by 25% over the past two weeks — another hopeful sign that the worst of the Delta wave may be behind us," per Axios' Sam Baker. The WHO is putting together a new group of scientists to look for evidence of the origins of COVID-19 in China and other countries, the Wall Street Journal's Drew Hinshaw and Betsy McKay report. Pfizer's CEO said the company will release vaccine data for children under the age of 5 before the end of the year, per the Atlantic's Sarah Zhang. |     | | | | | | 6. Something wondrous |  | | | A composite image of Valles Marineris canyon on Mars from video taken by NASA's Mars Odyssey spacecraft. Photo: NASA/Arizona State University via Getty Images | | | | NASA's InSight lander detected a 90-minute marsquake on the Red Planet — the longest measured yet. The big picture: Like Earth, Mars is seismically active. But even the biggest earthquakes shake Earth at the frequencies picked up by seismometers for no more than 20 minutes, says Bruce Banerdt, principal investigator of InSight at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Details: In August and September, the lander recorded three quakes with a magnitude greater than 4.0, the space agency reported last week. Before then, the most intense marsquake recorded registered at 3.7. - One kept vibrating and rolling through Mars for an hour and a half.

- Its source isn't clear, though it appears to have come from nearly 5,300 miles away. One candidate is the Valles Marineris canyon, according to Banerdt.

How it works: Mars' crust is believed to be more cracked than Earth's. Banerdt thinks when the waves left the source of the quake, some may have directly hit the seismometer while others traveled through the planet and reflected off its cracks, eventually being detected. - The frequency of the waves in marsquakes is similar to that of quakes on Earth, suggesting it is the same process of a fast break and movement in a fault that sets off the waves, Banerdt says.

- "We don't have a reason to believe there is something happening at the source that would make it shake longer."

What it means: On Earth, the crust is broken as well, but those cracks tend to heal over time — water dissolves minerals and cements the cracks back together. - One theory then is that the scattering of waves on Mars might be related to the amount of water in the Martian crust.

- On the Moon, which is very dry and has extensive cracks from meteorite impacts, moonquakes can reverberate for hours, according to data from the Apollo missions.

The intrigue: Banerdt says they expect the length of Mars' quakes to be somewhere between those on the Moon and Earth. - But interestingly, the waves from some marsquakes scatter a lot, whereas others don't.

- "The implication is maybe that Mars' crust isn't the same everywhere," he says.

|     | | | | | | A message from Abbott | | Kids back in school? Our tech can help ease your mind | | |  | | | | After COVID-19 kept many kids out of the classroom, students around the country are rejoining classmates in school. Just because they're out of sight doesn't mean they're out of mind. From testing to diabetes care, Abbott technologies can help. | | |  | | It'll help you deliver employee communications more effectively. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters. If you're interested in advertising, learn more here.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1300, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment