| | | | | | | Presented By University of Central Florida | | | | Axios Science | | By Alison Snyder · Apr 21, 2022 | | Thanks for reading Axios Science. This week's edition is 1,629 words, about a 6-minute read. | | | | | | 1 big thing: Climate change and farming driving loss of some insects |  | | | Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios | | | | As the sheer number and types of insects living on Earth's land decreases, scientists are beginning to determine the impacts of habitat loss, climate change and other threats on insect populations worldwide. What's new: The combined consequences of climate change and high-intensity agriculture may be driving declines in insects — on average by 49% in some of the most impacted places, according to a study published this week in Nature. Why it matters: Insects that pollinate crops, cycle nutrients into soil, and eat pests are linchpins in the ecosystems that produce food. - A finer picture of the global insect decline — which species are affected and where — could help to better inform international agreements to protect biodiversity.

Details: Charlotte Outhwaite, a research associate at University College London, and her colleagues found a 27% drop in the number of insect species in places experiencing the highest temperature increases and where one crop is grown or large amounts of pesticides are used. (Agriculture and other changes in land use can alter the microclimate in an area.) - But in farmland near natural habitats, the reductions in insect biodiversity were less dramatic, even if those places experienced climate warming.

- That's consistent globally, Outhwaite says, adding it will "hopefully be applicable in most contexts" and could "provide alternative resources to help protect insect biodiversity in the future when it is likely further warming will occur."

Insects in heavily farmed regions of the tropics were particularly hard hit, based on data collected in a 20-year period for nearly 17,900 species of beetles, flies, butterflies, bees and other insects from more than 6,000 places around the world, the researchers found. - Tropical insects evolved in a narrow temperature range, and it is possible they are already living close to their climate limits, Outhwaite says, adding that because there is less data from tropical regions, the impact there is likely even worse.

The big picture: Studies have pointed to massive losses of insects — but not everywhere and not among every species of insect. - The abundance of some insects — for example, some arthropod species in the Arctic and freshwater insects— and the range of others, including some butterfly species in Europe and mosquitoes —haven't changed or have increased as the climate, people, and how they use land and water shifts.

- A study published this week found warmer spring temperatures in the U.S. Rocky Mountains are associated with an increase in smaller bees and a decrease in bumblebees and other larger species, which could reorder bee communities that are crucial for pollination, the Guardian reports.

Between the lines: That suggests some good news for the world's insects, but the metrics of abundance and species richness (the number of species) that are commonly used to assess biodiversity may be masking the nuances of what is happening, Nature's Gayathri Vaidyanathan wrote last year. - For example, a study of Arctic arthropods found their total abundance dropped gradually from 1996 to 2014 before sharply increasing.

- But when researchers looked at the diversity of insect families, they found those increases appeared to be driven by a small number of types of insects.

- Another challenge is that data skews toward North America and Europe though some global-scale datasets are becoming available, Outhwaite says.

"There are definitely instances where insects are at risk and are declining," she says. - But, "whether it is as dire as some say, we don't have enough data to say one way or another."

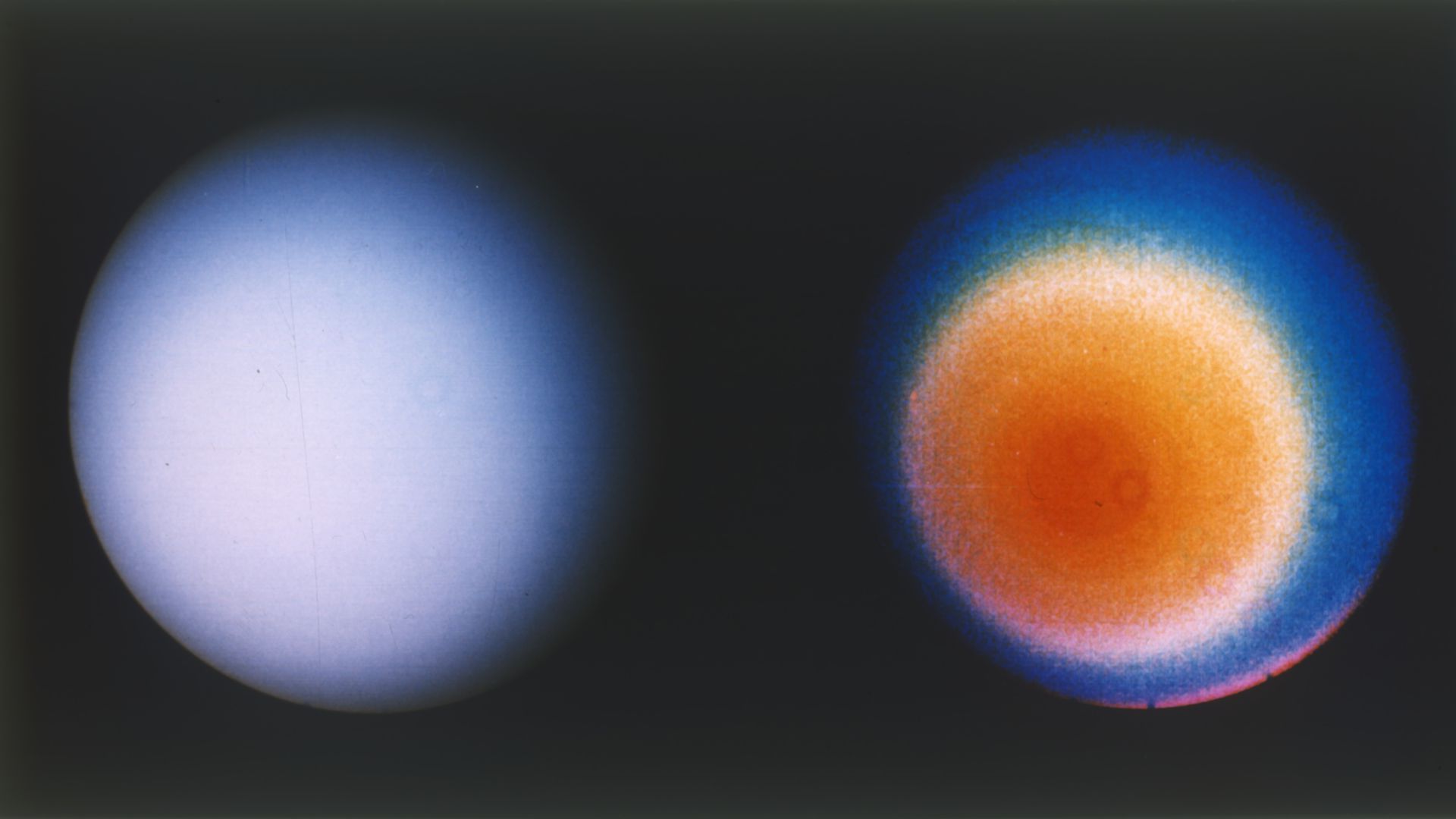

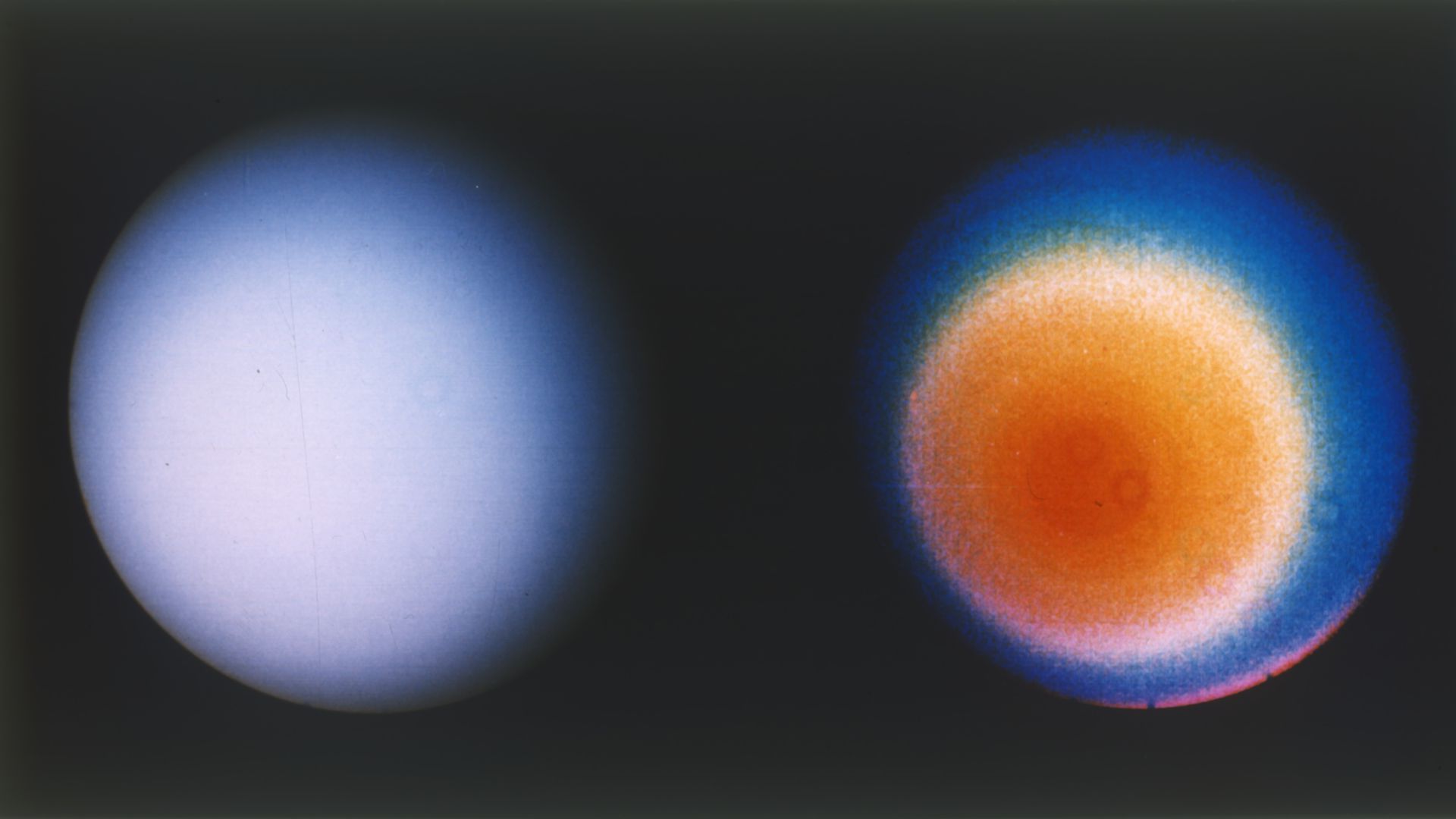

What to watch: Governments will convene in Côte d'Ivoire in about two weeks for the UN conference on the future of land management, which Outhwaite's study indicates has a strong impact on insect biodiversity. Go deeper. |     | | | | | | 2. Priority planets |  | | | The planet Uranus viewed by the Voyager 2 spacecraft in 1986. Photo: Heritage Space/Heritage Images/Getty Images | | | | A once-in-a-decade report released Tuesday recommended NASA and other space agencies study the planet Uranus within the next decade to better understand giant icy worlds in our solar system and beyond, Axios' Jacob Knutson reports. Why it matters: Proposals published by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine are not binding, but they are influential and often guide federal funding toward future space missions. The Committee on the Planetary Science and Astrobiology Decadal Survey designated the Uranus Orbiter and Probe as the highest-priority new flagship mission for initiation between 2023 and 2032, calling the planet "one of the most intriguing bodies in the solar system." - "Its low internal energy, active atmospheric dynamics, and complex magnetic field all present major puzzles. A primordial giant impact may have produced the planet's extreme axial tilt and possibly its rings and satellites, although this is uncertain," the report reads.

- The mission would deliver a probe to Uranus' atmosphere to better understand the planet's origin, interior, atmosphere, magnetosphere, rings and satellites.

The Enceladus Orbilander, the second-highest priority mission flagged in the report, would entail exploring Saturn's sixth-largest moon, specifically for evidence of life beyond Earth in the water-rich plumes spewing into space from the planet's subsurface ocean. - The Cassini spacecraft in 2017 discovered the plumes contained hydrogen, suggesting there are probably hydrothermal vents at the bottom of Enceladus' sea. Scientists have proposed that conditions around those underwater vents could support life.

- The proposed Orbilander would analyze plume material from orbit and during a two-year landed mission to better understand the habitability of Enceladus' ocean.

What they're saying: "This report sets out an ambitious but practicable vision for advancing the frontiers of planetary science, astrobiology and planetary defense in the next decade," said Robin Canup, assistant vice president of the Planetary Sciences Directorate at the Southwest Research Institute and co-chair of the National Academies' steering committee for the report. The big picture: For the first time, the report also recommended NASA and other agencies prioritize planetary defense by detecting and tracking objects that pose a threat to life on Earth, saying this proposal was "more concerned with human health and safety rather than the advancement of scientific understanding." |     | | | | | | 3. Catch up quick on COVID |  Data: GISAID; Chart: Will Chase/Axios Omicron subvariant BA.2.12.1 now accounts for about 20% of new COVID cases in the U.S., per Axios' Erin Doherty. Go deeper: Axios' Coronavirus Variant Tracker. Scientific American and the NYT looked at the challenges of assessing the personal and community risks of COVID-19. "[T]here are still many mysteries about the virus and the pandemic it caused," STAT journalists write in outlining six open science questions about SARS-CoV-2. Smart watches and other wearable devices can "track the progression of COVID and even show how sick an individual becomes through their heart rate," Axios' Tina Reed reports on a study published this week. |     | | | | | | A message from University of Central Florida | | The frontline of cyber defense innovations | | |  | | | | The University of Central Florida's (UCF) Cyber Security and Privacy cluster examines the social implications that new technology has on our lives. The goal: Develop innovative solutions for security and privacy issues that arise in business and life. Learn about UCF's hub for cyber innovation. | | | | | | 4. Watchdog: Political interference underreported at CDC, FDA |  | | | Illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios | | | | CDC, FDA and NIH employees didn't report what they viewed as political interference in their work during and before the pandemic because they feared retaliation, Axios' Adriel Bettelheim reports from a new federal audit. The big picture: Allegations of political interference affecting mask-wearing guidelines and other scientific decisions during the Trump administration raised concern about scientific integrity policies. - That led the Government Accountability Office to review oversight within HHS.

What they're saying: Employees at the agencies reviewed said they observed incidents they perceived as political meddling but didn't report them, in part out of fear and in part because they didn't know how, GAO found. - Some of the interference was believed to have led to the alteration of public health guidance and delayed publication of COVID-19 scientific findings.

- No formal reports of potential political interference were logged at the federal health agencies in question from 2010 through 2021, GAO said, likely due to a lack of guidance.

Only NIH includes information on political interference in scientific decision-making in its scientific integrity training. What's next: GAO made seven recommendations, mostly surrounding enhanced training and reporting. - HHS said it has formed a working group with representatives of the relevant agencies to update scientific integrity policies.

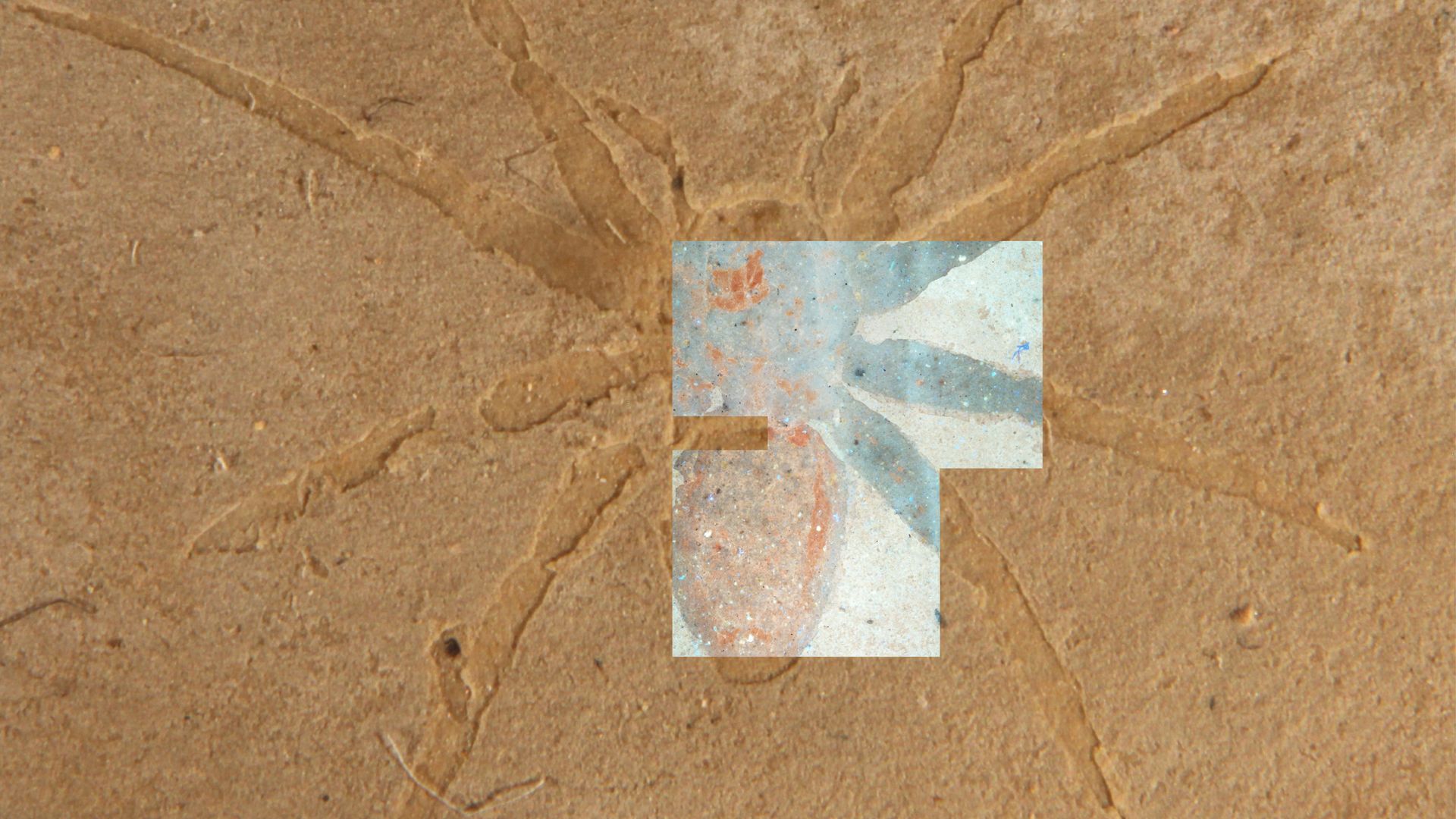

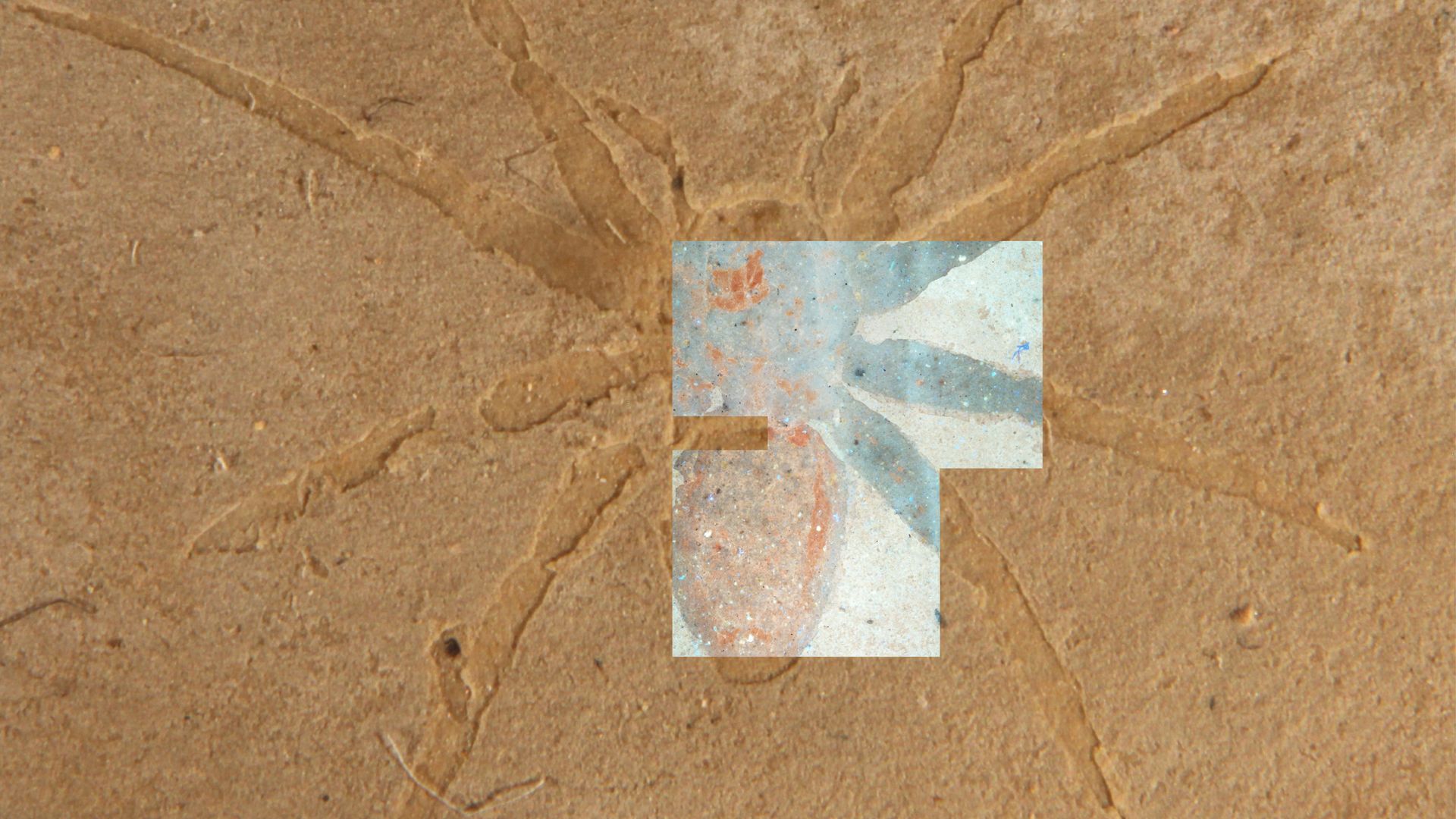

|     | | | | | | 5. Worthy of your time | | Viruses are not always the villain (Saima Sidik — Hakai) Biotech firm announces results from first U.S. trial of genetically modified mosquitoes (Emily Waltz — Nature) A new nuclear imaging prototype detects tumors' faint glow (Anna Gibbs — Science News) Can we fall out of love? (Allison Hope — NYT) |     | | | | | | 6. Something wondrous |  | | | Fossilized spider from the Aix-en-Provence Formation in France with fluorescent microscopy image of the same fossil overlaid. Credit: Alison Olcott | | | | Tiny diatoms may have helped record life on Earth, according to new research. The big picture: Bones, teeth, shells and other mineralized features of life are captured in stone but the feathers, skins and exoskeletons of insects and arachnids often disappear into Earth's history. What they found: Fluorescence microscopy revealed little claws, hairs and other tiny features on 22.5-million-year-old spider fossils found in a lakebed in France, researchers wrote this week in Communications Earth & Environment. - They also found thick mats of spherical- and needle-shaped diatom on the fossils and, using scanning electron microscopy, a sticky black material secreted by diatoms covering the spiders' bodies.

- Through chemical analysis, the researchers determined the polymer was composed of carbon and sulfur, which they suggest could be preserving the spiders.

Scientists noted diatoms before in many of the world's rich fossil deposits and hypothesized that the substance from the microalgae created an oxygen-free environment that allowed soft tissues to be preserved. - But the material could be doing something else: It may be providing the chemical building blocks that allow preservation to happen, says Alison Olcott, an associate professor of paleobiogeochemistry at the University of Kansas and an author of the study.

- The substance might be reacting with the spider's exoskeleton and preserving the arachnids.

What's next: There are "tantalizing hints" that this happened widely, says Olcott, who adds a next step would be to apply these methods to fossils found in similar lakebeds. - "These exceptional fossils sites provide a wonderful snapshot of what Earth was like in the past," she says. They're a "window into how life has adapted and evolved at times of climate change."

|     | | | | | | A message from University of Central Florida | | The frontline of cyber defense innovations | | |  | | | | The University of Central Florida's (UCF) Cyber Security and Privacy cluster examines the social implications that new technology has on our lives. The goal: Develop innovative solutions for security and privacy issues that arise in business and life. Learn about UCF's hub for cyber innovation. | | | | Thanks to Aïda Amer and Will Chase on the Axios' visuals team, to Laurin-Whitney Gottbrath and Andrew Freedman for editing and to Carolyn DiPaolo for copy editing this week's newsletter. |  | It's called Smart Brevity®. Over 200 orgs use it — in a tool called Axios HQ — to drive productivity with clearer workplace communications. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters. If you're interested in advertising, learn more here.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1300, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment