| | | | | | | | | | | Axios Science | | By Alison Snyder ·Mar 10, 2022 | | Welcome back to Axios Science. This week's edition is 1,421 words, about a 5-minute read. - Send your feedback and ideas to me at alison@axios.com. You can reach Eileen Drage O'Reilly at eileen@axios.com.

- 🎧 "How it Happened," Season 4, focused on the slow-motion path to Russia's invasion of Ukraine, is now available for download. Listen.

- Sign up here to receive this newsletter.

| | | | | | 1 big thing: How COVID can damage the brain |  | | | Illustration: Rebecca Zisser/Axios | | | | The mystery of how SARS-CoV-2 may cause brain fog or other neurological symptoms in some people is driving new global research, Axios' Eileen Drage O'Reilly writes. Why it matters: Roughly 79 million Americans contracted COVID-19 in the first two years of the pandemic. While most survived, many are grappling with long-term symptoms, or long COVID, that affect the brain and other body systems. - "Neuro-long COVID is a very important problem in the U.S. It affects millions of people and leads to people not being able to work the way they used to, or to lose time from work," Igor Koralnik, chief of neuro-infectious diseases and global neurology at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, tells Axios.

- There's an "urgent need" to research the disorders and develop therapies, NIH's Avindra Nath and Yale's Serena Spudich wrote earlier this year.

How it works: Some of the big questions researchers are trying to answer include if and how the virus is breaching the protective blood-brain barrier, how it is damaging the brain, and if the effect is permanent. - Most of the accumulated data so far is based on adults, so there's less known about how the virus affects the brains of older teens or children and infants.

Accessing the brain: The blood-brain barrier often prevents many germs from reaching the brain, but certain pathogens are able to breach it. - Whether SARS-CoV-2 has the ability to directly cross that barrier remains in question, although recent studies indicate it can.

- Autopsies have also found SARS-CoV-2 infections in cells near the brain can inflame the brain-barrier cells and that this inflammation can be relayed into the brain's neurons and glial cells.

- Koralnik's team published a study this week that found biomarkers in blood plasma that suggest the brain's supportive glial cells are activated — indicating there is inflammation — and neurons were found to be damaged in both long COVID patients who'd had mild disease and those who had been hospitalized with severe symptoms.

Tracking damage: Some MRI studies link brain lesions to the virus, although those were not found in all patients. - A study of 785 people aged 51 to 81 published this week in Nature indicates COVID can shrink the size of the brain, so that months after infection some people show as much as a decade of normal aging.

- People infected with even mild cases showed cognitive decline, degeneration in parts of the brain, and brain shrinkage, says co-author Anderson M. Winkler, senior associate scientist at the National Institute of Mental Health.

Long-term implications: Whether this damage is permanent is unknown as the brain has a remarkable ability to recover or compensate for certain damage. - But, there is some concern it might accelerate or trigger early Alzheimer's or Parkinson's diseases.

- A JAMA Neurology study out this week followed 1,438 COVID survivors and 438 uninfected people from Wuhan, China, all 60 or older, for more than a year. They found a "markedly higher" risk of dementia in those who had experienced severe COVID. The risk appears to increase for those with mild symptoms as well.

- But Winkler says there's still much unknown.

What's next: NIH and others are working to determine if the changes are reversible, if they affect younger individuals the same as older ones, if changes in the brain are directly related to the brain fog people experience, and what the best therapeutic options will be. |     | | | | | | 2. Catch up quick on COVID |  Data: N.Y. Times; Cartogram: Kavya Beheraj/Axios "Coronavirus cases have continued to plummet nationally and in nearly all states, and daily deaths are also dropping," per Axios' Caitlin Owens and Kavya Beheraj. More than 6 million people around the world have now died from COVID-19, David Rising reports for the AP. Two new reports outline disease surveillance, next-generation PPE and other measures to prepare for future pandemics, Axios' Tina Reed writes. Wastewater monitoring is being used around the world to track COVID but "the jury is out on just how useful the technology is," Gretchen Vogel reports in Science. |     | | | | | | 3. Giant spiders could spread across the East Coast |  | | | A jorō spider in Georgia. Photo: University of Georgia | | | | An invasive species of spider the size of a child's hand could spread across the East Coast this spring, Axios' Karri Peifer writes. Why it matters: Large jorō spiders — millions of them — are expected to begin "ballooning" up and down the East Coast as early as May. - Researchers have determined jorō spiders (Trichonephila clavata) can tolerate cold weather, but are harmless to humans as their fangs are too small to break human skin.

- The spider, which is native to Japan, began appearing in the U.S. about a decade ago but was confined to the southeast and specifically Georgia, according to NPR.

- They fanned out across the state using their webs as parachutes to travel with the wind.

- Andy Davis, author of the study and a researcher at the University of Georgia's Odum School of Ecology, tells Axios it isn't certain how far north the spiders will travel, but they could make it to D.C. or even Delaware.

What they found: Davis and his colleagues compared sightings and physiological features of the jorō spider with a closely related species — the golden silk spider — that has been limited to the same region of the U.S. for at least 160 years. - They report the jorō spider's metabolism is twice as high as the golden spider's, its heart rate is 77% higher when it is exposed to low temperatures, and it can survive better in a brief freeze.

- That suggests the Jorō spiders could exist in regions colder than the southeastern U.S. that are above freezing for more than six months, Davis says.

The details: Jorō spiders are bright yellow, black, blue and red and can grow to about 3 inches long. - They likely traveled around the globe on shipping containers.

- They're named for Jorōgumo, a spider-like creature of Japanese folklore that can shapeshift into a woman to seduce its prey.

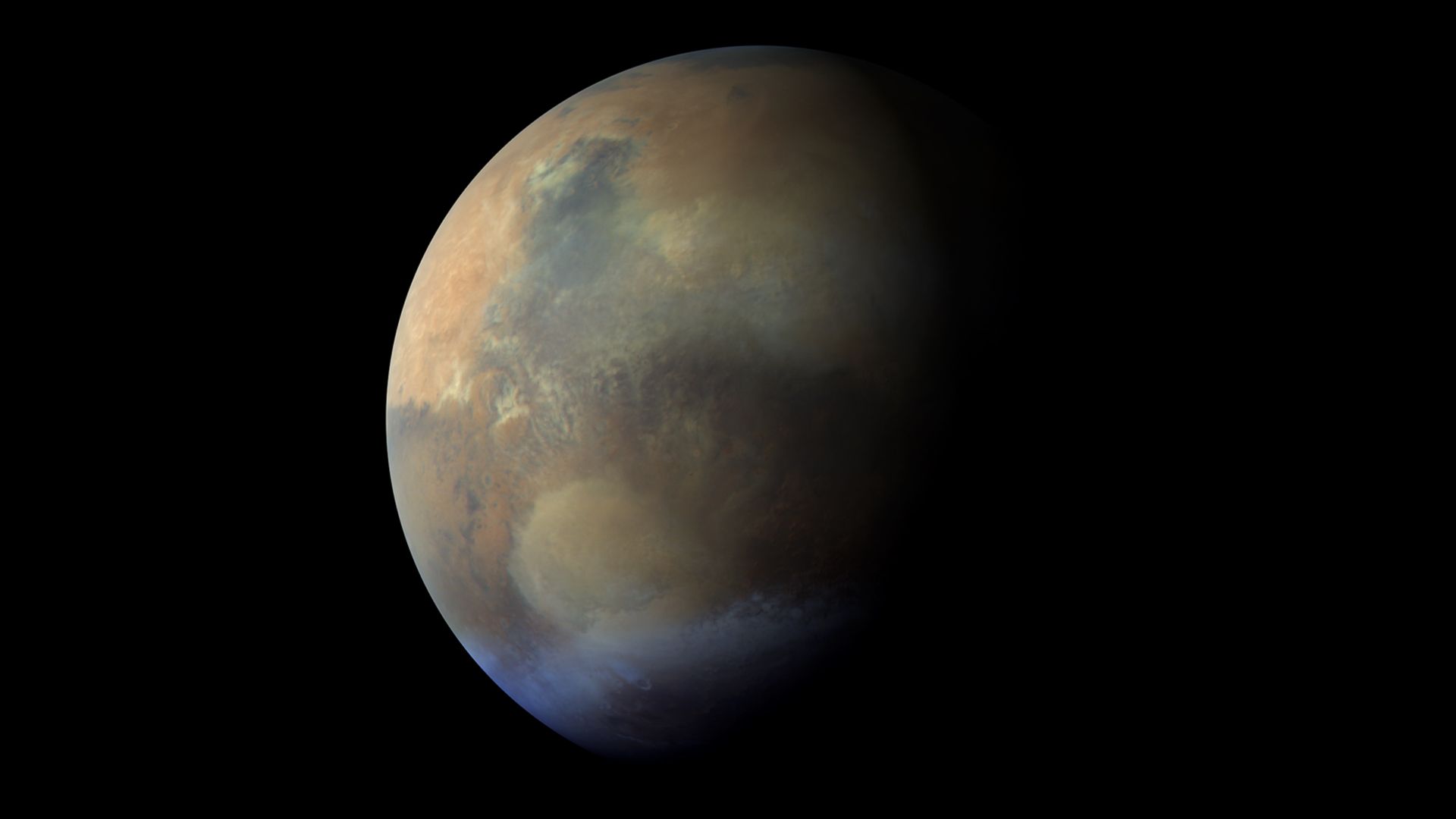

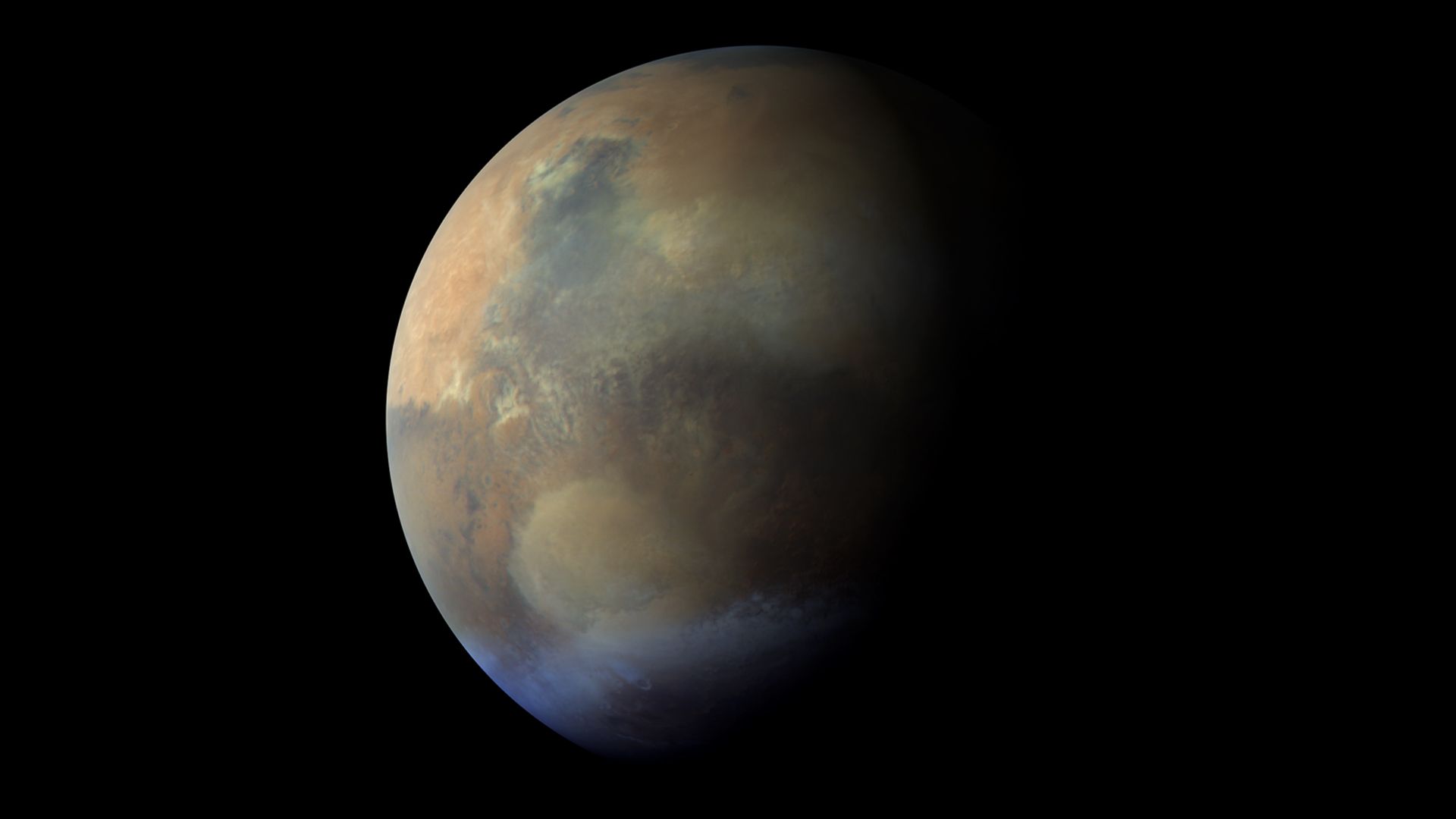

|     | | | | | | A message from Axios | | Tech news worthy of your time | | |  | | | | Catch up on the top tech stories in just a few short minutes with Axios Login. Why it matters: Get the tech insights from Silicon Valley and DC that impact our lives Subscribe for free. | | | | | | 4. Worthy of your time |  | | | 3D-printed statues outside the Smithsonian Castle in Washington, D.C., honor women in STEM. Photo: Alex Wong/Getty Images | | | | The famous and forgotten women of STEM (JSTOR Daily) Western nations cut ties with Russian science, even as some projects try to remain neutral (Richard Stone — Science) U.S. scientist falsely accused of hiding ties to China speaks out (Natasha Gilbert — Nature) John von Neumann thought he had the answers (Samanth Subramanian — The New Republic) |     | | | | | | 5. Something wondrous |  | | | A color composite of images of Mars collected at three wavelengths. The contrast has been adjusted to enhance the visibility of surface and atmospheric features. Image: Emirates Mars Mission | | | | As the earthly new year rang in, a mighty dust storm was growing on Mars — a process captured by the United Arab Emirates' Hope probe. Why it matters: Dust storms play a role in the Red Planet's atmosphere — and could help explain how it became so thin. - Sunlight is absorbed by dust in the atmosphere, warming it and creating large temperature differences between the surface and mid-atmosphere.

- As air flows from an area of high pressure to low pressure, winds build and put more dust into the atmosphere, further heating it and strengthening the winds.

"These dust storms are, in Martian terms, violent events that impact all layers of the atmosphere, lifting aerosols and changing the concentration and distribution of gases in the atmosphere," Hessa Al Matroushi, science lead of the mission, tells Axios in an email. Catch up quick: The Emirates Mars Mission's (EMM) Hope probe has been orbiting the Red Planet for 13 months, collecting data about water and carbon dioxide ice clouds and dust storms below with a high-resolution camera and infrared and ultraviolet spectrometers. - From its orbit, the probe can cover more of the planet, providing finer scale data to understand the weather and climate in different parts of Mars over the course of a Martian day and year (about 687 Earth days).

How it works: The camera system takes images at five different wavelengths, in this case over a two-week period starting on Dec. 29, 2021. - The dark triangle in the upper left quadrant of the image above — taken on Jan. 7 and released by EMM this week — is a feature known as Syrtis Major. The tan circle below it is the Hellas impact basin, which is "often shrouded in dust and water-ice clouds," Steve Lee, a member of the science support team said.

- In the image, taken in the middle of the day, the dust clouds and hazes (tannish) and water-ice clouds (blue-gray) are to the east and northwest of Syrtis Major and to the north of Hellas.

The storm lifted dust from the surface and carried it nearly 2,500 miles from where it originated. What's next: Mars' southern hemisphere is heading into spring, a time when dust storms typically spread even more, Lee said. |     | | | | | | A message from Axios | | Tech news worthy of your time | | |  | | | | Catch up on the top tech stories in just a few short minutes with Axios Login. Why it matters: Get the tech insights from Silicon Valley and DC that impact our lives Subscribe for free. | | | | Thanks to Carolyn DiPaolo for copy editing this week's newsletter. |  | It's called Smart Brevity®. Over 200 orgs use it — in a tool called Axios HQ — to drive productivity with clearer workplace communications. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters. If you're interested in advertising, learn more here.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1300, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment