| | | | | | | Presented By MethaneSAT | | | | Axios Science | | By Alison Snyder ·Nov 18, 2021 | | Thanks for reading Axios Science. This week's newsletter is 1,578 words, about a 6-minute read. - We'll be off next week for Thanksgiving and back in your inbox on Dec. 2.

- Send your feedback and ideas to me at alison@axios.com.

- Did someone forward this to you? Sign up here.

| | | | | | 1 big thing: Archaeologists dig into digital data |  | | | Illustration: Shoshana Gordon/Axios | | | | Hidden parts of deep human history are being revealed by digital tools that generate new troves of data for archaeologists to analyze and preserve. Why it matters: On-the-ground excavation can be expensive, time-intensive and destructive. Digital techniques — if researchers can access them — could help to focus their search and hasten discoveries. - "These new technologies are allowing us to think more carefully about where we do hand excavation and where we can learn without excavating at all," says Elaine Sullivan, an Egyptologist at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

What's happening: Light detecting and ranging (lidar) measurements, virtual reality, 3D modeling and other technologies have become powerful tools for archaeologists. - Aircraft-based lidar — which emits a laser pulse and measures the return time of light reflected from an object or feature of a landscape to determine the distance to it — can penetrate vegetation and give a precise 3D image of the ground below.

- But it has also revealed massive features concealed by their sheer size, even in more open land.

In a recent study, archaeologists analyzed lidar data and found nearly 500 new Mesoamerican sites across a large swath of southern Mexico. - "Many sites were hidden in plain sight," says archaeologist Takeshi Inomata of the University of Arizona.

- The structures were likely built between 1050 B.C. and 400 B.C., and features of their remnants suggest the Olmec and the Maya civilizations interacted, Inomata and his colleagues report in the journal Nature Human Behaviour.

The intrigue: Mayans built a large structure — Aguada Fénix — between 1,000 and 800 B.C., just as they were transitioning to a more sedentary way of life, but "we don't see evidence of very much developed social inequality," Inomata says. - The site — and a handful of others — is part of emerging evidence that suggests the construction of monuments, cultural centers and other features of civilization might not depend on societies developing the hierarchy and inequality that was long seen as an inevitable consequence of development.

What's next: Where there's data, there's usually AI close behind, and archaeologists are adapting algorithms to analyze lidar and other data from remote sensing. - Leila Character, a graduate student at the University of Texas, Austin, is training a deep learning algorithm for object detection on more than 17,000 features of structures Inomata mapped at one archaeological site. She plans to then run the algorithm on unlabeled data from other sites to try to then find new sites, with confirmation in the field to follow.

What to watch: How the field moves to preserve and standardize all this amassing data. - It's not just information about structures and artifacts themselves but also about the environment objects are excavated from that contains valuable information about connections between artifacts.

- These objects can never be excavated again, says Sullivan, who is using GIS and 3D modeling to recreate Saqqara, Egypt's oldest known pyramid built around 2630 B.C., and its surroundings.

- "In 150 years, are archaeologists going to be able to access and reuse this digital data?" Sullivan says. "If the answer is no, we have a real problem."

Go deeper. |     | | | | | | 2. Fear and loneliness caused surge of early pandemic calls for help |  Fear and loneliness replaced relationship and livelihood concerns during the pandemic, a team of scientists said after looking at millions of helpline calls in multiple countries before and after the COVID-19 pandemic started, Axios' Eileen Drage O'Reilly reports. The big picture: Doctors and policymakers are trying to assess the impact of quarantines, school closures and other public health measures on our emotional and mental well-being. Using helpline data could become an important assessment tool, the researchers said. - "When it comes to tracking mental health, we are so far behind," says Cindy Liu, director of the Developmental Risk and Cultural Resilience Laboratory at Brigham and Women's Hospital, who published a perspective piece in Nature.

- The impact of pandemic measures on mental health was unclear because "we have no historical data to compare these situations to," says Marius Brülhart, professor of economics at the University of Lausanne and co-author of the study, published Wednesday in Nature.

What they found: The team examined 8 million calls or texts to 23 helplines in 14 EU countries, the U.S., China, Hong Kong, Israel and Lebanon from 2019 to early 2021. - They found a 35% rise on average in helpline calls, which peaked about six weeks after the initial outbreak.

- "We were really interested to see what was behind the increase in the calls, and we were kind of relieved to see there were two main motives for people to call: They were anxious about the virus and anxious about getting infected. The other one was loneliness, [as] people with stay-at-home orders were cut off from their social circle," Brülhart says.

- The risk of suicide did not appear to increase, he says, matching U.S. reports showing a national decline in 2020.

Read the entire story. |     | | | | | | 3. Catch up quick on COVID-19 |  Data: N.Y. Times; Cartogram: Kavya Beheraj/Axios "Coronavirus cases are rising, nationally and in most states — an ominous trend heading into the week of Thanksgiving," per Axios' Caitlin Owens and Kavya Beheraj. A new study predicted which animals are likely reservoirs for SARS-CoV-2, findings that could help to prioritize species for testing and surveillance of spill back events, Emma Yasinski reports in The Scientist. NIAID director Anthony Fauci said this week that COVID-19 could be reduced to an endemic illness in the U.S. next year from the current emergency phase, if vaccination rates increase, per Reuters' Julie Steenhuysen. |     | | | | | | A message from MethaneSAT | | We need to cut methane fast. Our first-of-its-kind satellite can help | | |  | | | | The U.S. joined over 100 countries in a pledge to slow global warming by cutting methane emissions 30% by 2030. MethaneSAT, a methane tracking satellite scheduled to launch in 2022, will help countries and companies meet this pledge to address the climate crisis. Learn more at MethaneSAT.org. | | | | | | 4. A new kind of propulsion could aid in space exploration |  | | | Side view of a flight model of the propulsion system firing in a vacuum chamber. Photo: ThrustMe | | | | A new kind of fuel for small satellites was successfully tested in space for the first time, Axios' Miriam Kramer writes. Why it matters: Iodine electric propulsion could offer new ways for tiny satellites to explore the solar system and enable spacecraft to avoid collisions in orbit, according to the company behind the technology, ThrustMe. - Analysts predict thousands of new small satellites could launch into space in the coming years, and engineers are looking for efficient and less expensive ways to maneuver them in orbit and keep them out of the way of harmful space debris or other satellites.

What's happening: The iodine-fueled thruster — called NPT30-I2 — was launched aboard the Beihangkongshi-1 satellite sent to space by China's Long March 6 rocket in November 2020. - A new study in Nature detailing the mission suggests the novel thruster could act as an alternative for satellite companies looking to diversify the types of fuel they use in the future.

Context: Thrusters for small satellites typically run on xenon, a relatively rare and expensive gas that's not easy to produce. - ThrustMe's CTO and co-founder Dmytro Rafalskyi said in a statement that iodine-based propulsion is cheaper and the fuel is easier to work with than xenon.

- The new type of propulsion can also be used in a relatively small thruster, which is key for small satellites where every gram of weight counts toward performance.

Yes, but: "Iodine is highly corrosive, presenting a potential danger to electronics and other satellite subsystems," Igor Levchenko and Kateryna Bazaka, two researchers who weren't involved in the study, point out in a commentary. - And it takes about 10 minutes for the iodine to heat up, meaning it might be hard to maneuver satellites using the thruster in time if a quick-turnaround emergency occurs, they write.

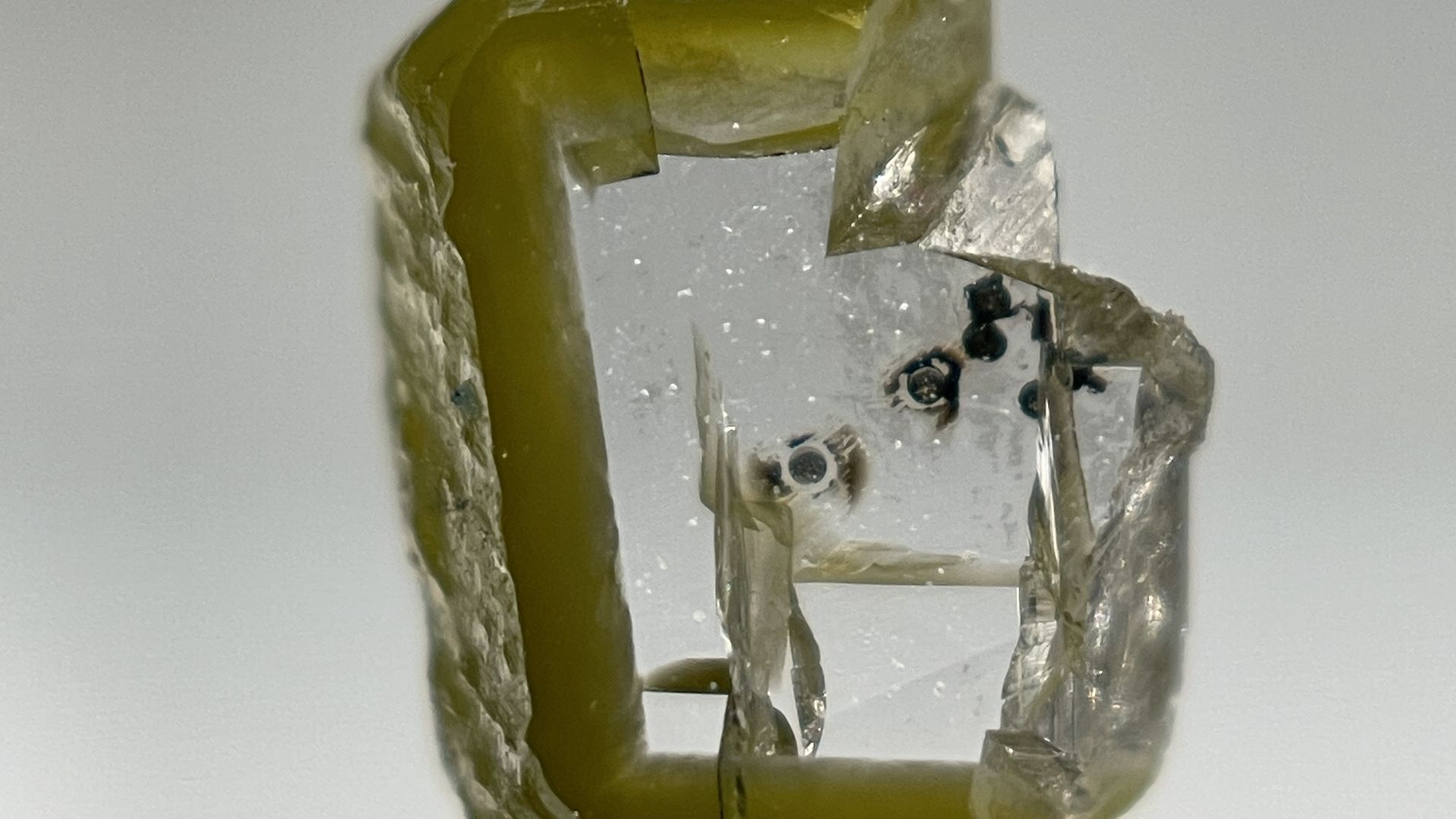

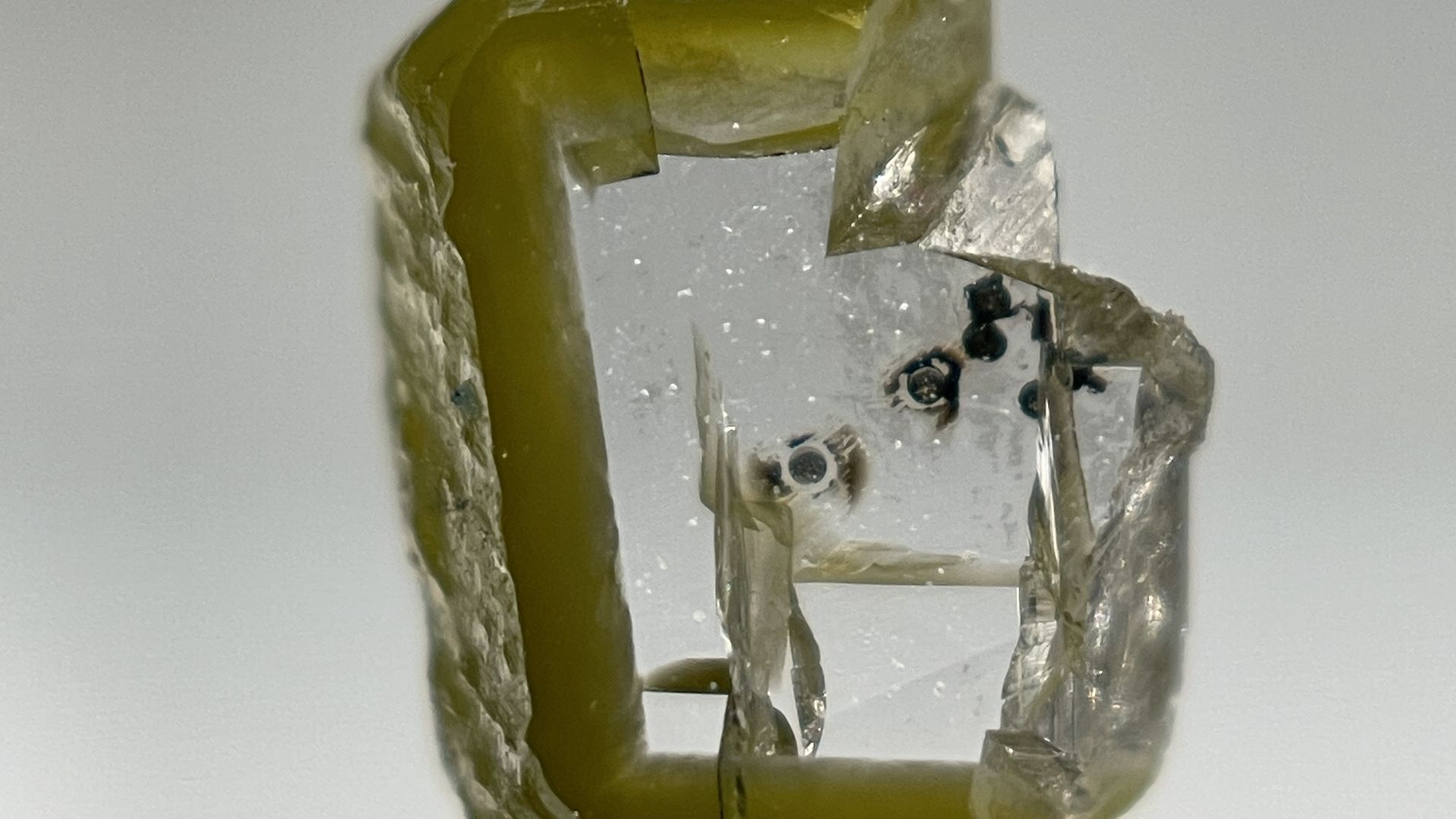

Go deeper: Russian anti-satellite test reveal dangers of space junk |     | | | | | | 5. Worthy of your time | | A little space rock with strange origins (Miriam Kramer — Axios) A new particle accelerator aims to unlock secrets of bizarre atomic nuclei (Emily Conover — Science News) A hope for Lyme disease? New vaccine targets ticks (Meredith Wadman — Science) Europe's Roma people are vulnerable to poor practice in genetics (Veronika Lipphardt et al. — Nature) |     | | | | | | 6. Something wondrous |  | | | The diamond that carried a new mineral to the surface of the Earth. Photo: Aaron Celestian/Los Angeles County Natural History Museum | | | | A mineral scientists sought for decades in nature has been found in a diamond mined from Botswana in the 1980s. The big picture: The mineral — predicted to exist by earlier experiments — forms in the intense pressure found deep within Earth's mantle. On the surface, it falls apart. - The diamond's strength maintained high enough pressures that the mineral survived in tiny inclusions — considered imperfections by jewelers and geochemistry gold mines by scientists — as the diamond moved to the surface.

What they found: Davemaoite — named by the researchers for pioneering experimental geophysicist Ho-kwang 'Dave' Mao — is composed mostly of calcium silicate. - But it is also rich in radioactive isotopes of potassium that generate heat in Earth's lower mantle, which helps to drive plate tectonics, Oliver Tschauner, a mineralogist at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and his colleagues reported last week in the journal Science.

The backstory: The green-rimmed diamond was acquired by Caltech in the late 1980s, where mineralogist George Rossman was interested in studying it to try to work out how gems get their colors. (They can come from ions of transition metal elements like iron or from defects, like those that give amethyst its purple hues.) - In the process, the researchers found inclusions of carbon dioxide in the diamond. Carbon dioxide can be in different phases — ice or gas — depending on the pressure it formed under, which is a valuable clue about Earth's interior.

- When they were studying those inclusions, Tschauner and his colleagues came across the calcium silicate perovskite and conducted a full analysis.

Davemaoite is abundant in Earth's lower mantle — it's just not accessible, Tschauner says. - He says the mineral was likely formed 410 to 560 miles deep within Earth. Pockets in the diamond that are at nearly 10,000 times atmospheric pressure protected the davemaoite as the diamond carried it to the surface.

|     | | | | | | A message from MethaneSAT | | We need to cut methane fast. Our first-of-its-kind satellite can help | | |  | | | | The U.S. joined over 100 countries in a pledge to slow global warming by cutting methane emissions 30% by 2030. MethaneSAT, a methane tracking satellite scheduled to launch in 2022, will help countries and companies meet this pledge to address the climate crisis. Learn more at MethaneSAT.org. | | | | Thanks to Shoshana Gordon for this week's illustration and to Amy Stern for copy editing this edition. |  | | It'll help you deliver employee communications more effectively. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters. If you're interested in advertising, learn more here.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1300, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment