| | | | | | | Presented By PL + US | | | | Axios Science | | By Alison Snyder ·Oct 28, 2021 | | Welcome back to Axios Science. This week's newsletter is 1,492 words, a 5-minute read. | | | | | | 1 big thing: Weighing COVID vaccines for kids |  | | | Illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios | | | | Polls suggest some parents are hesitant to vaccinate their young children against COVID-19, but the benefits outweigh the risks, several infectious disease doctors tell Axios' Eileen Drage O'Reilly. The latest: The FDA and CDC may soon authorize Pfizer's lower-dose vaccine for that age group, with Moderna close to also seeking approval. - The highly transmissible Delta variant changed the pandemic's trajectory: More people — including kids — started getting infected. Children comprise 16.5% of cases, with around 6 million infections and 700 deaths.

- "There's lots and lots of SARS-CoV-2 infection [in kids] out there," says Rohan Hazra, acting director of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development's Division of Extramural Research.

Yes, but: Public health efforts to persuade Americans to get vaccinated have struggled with bad messaging. - A recent Kaiser Family Foundation poll found about 3 in 10 parents say they will "definitely not get" a shot for their 5 to 11 year-olds.

- An Axios/Ipsos Coronavirus Index at the end of September found parents were split (44% likely / 42% unlikely) in allowing their 5 to 11 year-old children to get the vaccine.

Risks from vaccines are tracked closely by the FDA and CDC, Fauci and others say. Trial data found Pfizer's COVID shot so far carries very small risks. - If there were going to be serious side effects from a vaccine in young children, "usually you'd see some signal by now, in animal studies and in other age groups. ... There's been nothing like that, to my knowledge," says Amesh Adalja, senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security.

Between the lines: In general, the younger the person, the less of a chance there will be serious symptoms from a COVID-19 infection. - However, while most children have no serious symptoms, "we can't predict who will develop severe COVID, MIS-C or long COVID. The immunology of the whole spectrum of COVID in children is not well defined," says Danilo Buonsenso, a pediatrician at the Gemelli University Hospital in Rome, who has published papers on long COVID.

- "One thing we don't know is what the long-range effects are of a virus that enters your body and has the capability of inducing aberrant inflammatory and immunological responses," Fauci says.

- Hazra, who researches MIS-C and long COVID in children, tells Axios they are looking at how much of these ailments in children are from the SARS-CoV-2 virus and how much are from other pandemic stressors. This will need large cohort studies on the long-term effects.

What they're saying: "COVID-19 disrupts children's lives. And the more immunity in the population the better," Adalja says. - "This is something that makes them individually more resilient to the virus, and their schools and their organizations and the activities that they're part of more resilient to the virus," he adds.

- Buonsenso says this return to normalcy will also benefit kids' mental health.

- Not only could vaccination help prevent severe disease or long-term symptoms, but it could also "indirectly contribute to protect those younger than 5, who can still have severe COVID," Buonsenso adds.

Go deeper: |     | | | | | | 2. Catch up quick on COVID-19 |  Data: N.Y. Times; Cartogram: Kavya Beheraj/Axios "The U.S. is now averaging roughly 70,000 new cases per day, a 20% drop over the past two weeks," per Axios' Sam Baker. A common antidepressant may reduce the risk of severe COVID-19, CNN's Maggie Fox reports. "The story of epidemics remains a story about people: people who become sick, people who die, people whose lives are upended, people who care for others," Aimee Cunningham writes in her deep dive into epidemics past and present for Science News. Scientists commenting on pandemic policies and science are navigating internet fame — and hate, Kai Kupferschmidt writes for Science. |     | | | | | | 3. AI hints at how the brain processes language |  | | | Illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios | | | | Predicting the next word someone might say — like AI algorithms now do when you search the internet or text a friend — may be a key part of the human brain's ability to process language, new research suggests. Why it matters: How the brain makes sense of language is a long-standing question in neuroscience. The new study demonstrates how AI algorithms that aren't designed to mimic the brain can help to understand it. - "No one has been able to make the full pipeline from word input to neural mechanism to behavioral output," says Martin Schrimpf, a Ph.D. student at MIT and an author of the new paper published this week in PNAS.

What they did: The researchers compared 43 machine-learning language models, including OpenAI's GPT-2 model that is optimized to predict the next words in a text, to data from brain scans of how neurons respond when someone reads or hears language. - They gave each model words and measured the response of nodes in the artificial neural networks that, like the brain's neurons, transmit information.

- Those responses were then compared to the activity of neurons — measured with functional magnetic resonance (fMRI) or electrocorticography — when people performed different language tasks.

What they found: The activity of nodes in the AI models that are best at next-word prediction was similar to the patterns of neurons in the human brain. - These models were also better at predicting how long it took someone to read a text — a behavioral response.

- Models that exceled at other language tasks — like filling in a blank word in a sentence — didn't predict the brain responses as well.

Yes, but: It's not direct evidence of how the brain processes language, says Evelina Fedorenko, a professor of cognitive neuroscience at MIT and an author of the study. "But it is a very suggestive source of evidence and much more powerful than anything we've had." - The finding may not be enough to explain how humans extract meaning from language, Stanford psychologist Noah Goodman told Scientific American, though he agreed with Fedorenko that the method is a big advance for the field.

The intrigue: There was one robust but puzzling finding, Schrimpf says. - AI models can be trained on massive amounts of text or they can be untrained.

- Schrimpf said he expected the untrained models to give poor predictions of the brain responses, but they found the models are decent at it.

- It could be there is an inherent structure that pushes untrained models in the right direction, he says. Humans are similar — our untrained brains are "a good start state from which you can get something without optimizing to real world experiences."

The bottom line: A common criticism of research comparing AI and neuroscience is that both are black boxes, Fedorenko says. "This is outdated. There are new tools for probing." Go deeper: - Meet the AI that can write (Axios)

- Looking to AI to understand how we learn (Axios)

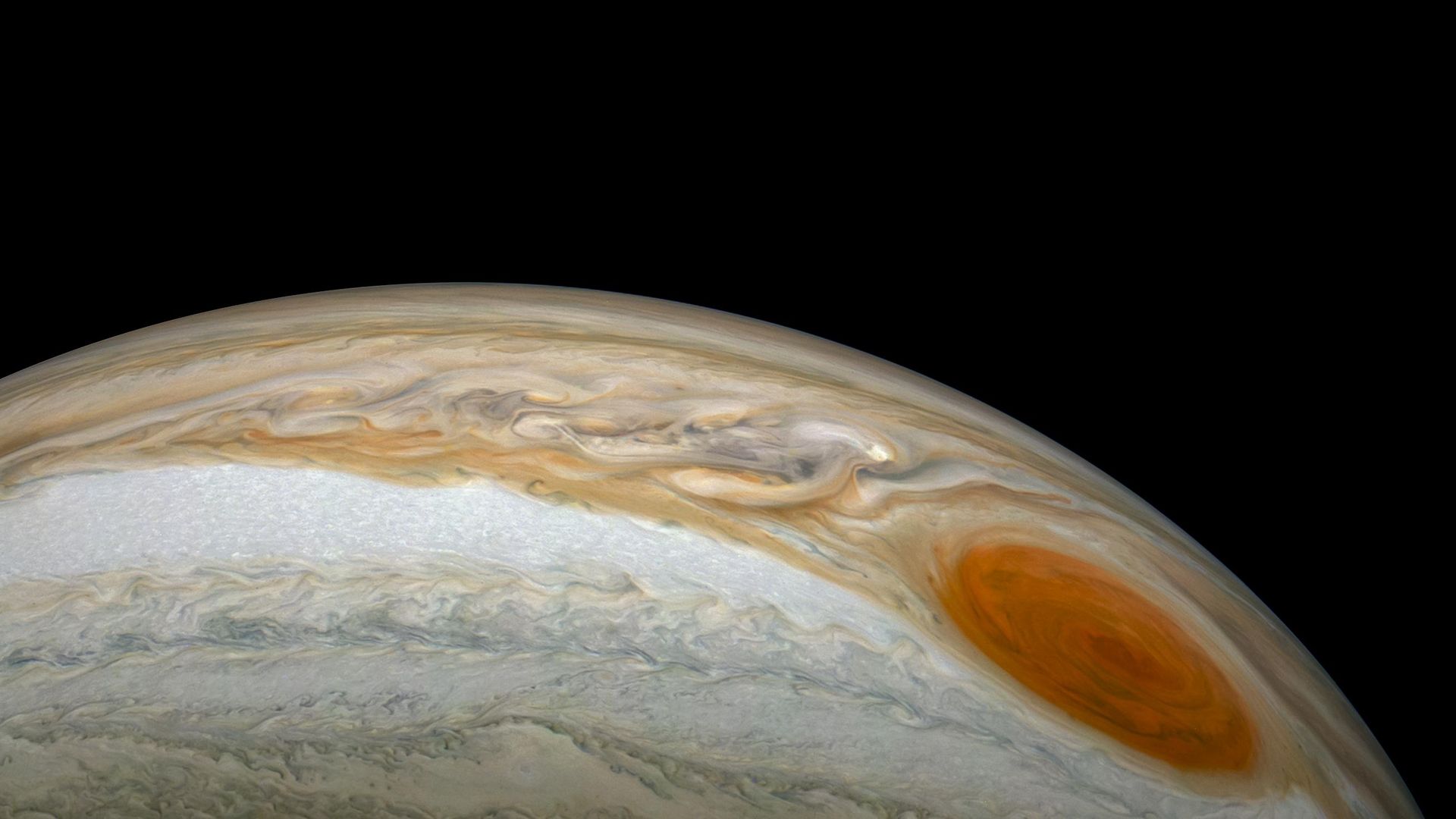

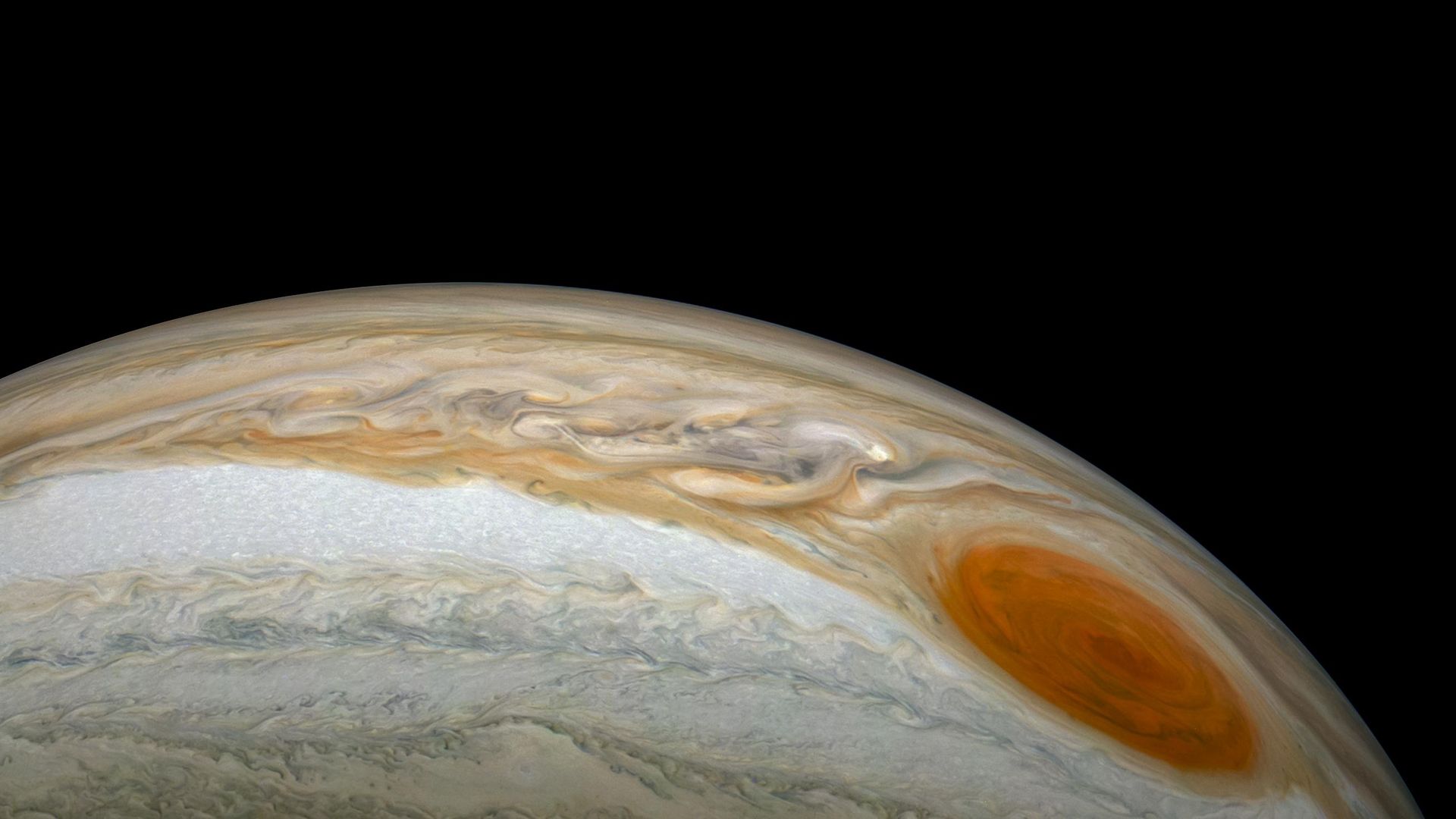

|     | | | | | | A message from PL + US | | Opioid recovery starts with access to a paid national leave policy | | |  | | | | Addiction treatment and recovery groups, organizations and businesses urge Congress to pass a national paid leave program in the Build Back Better legislative package. The reason: This program would make treatment more accessible for 20 million Americans with substance use disorders. | | | | | | 4. Worthy of your time |  | | | Smoke blankets the black spruce forests just north of Fairbanks, Alaska, in 2004. Photo: Ashley Cooper/Corbis via Getty Images | | | | Arctic wildfires threatening North America's black spruce trees (Chen Ly — New Scientist) Sitting Bull's great-grandson identified using new DNA technique (Katie Hunt — CNN) An ultra-precise clock shows how to link the quantum world with gravity (Katie McCormick — Quanta) A whole new world (Razib Khan — Substack) |     | | | | | | 5. Something wondrous |  | | | Jupiter's Great Red Spot from Juno. Image: Enhanced by Kevin M. Gill (CC-BY) based on images provided courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS | | | | Massive and drifting slowly across Jupiter, the Great Red Spot extends hundreds of miles into the planet's atmosphere, new data from NASA's Juno mission reveals. Why it matters: By studying the depths of Jupiter, researchers can learn more about how the planet formed and shaped the development of others in the solar system, and how weather works on other worlds. What they found: Data from two instruments on NASA's Juno mission show the Great Red Spot is between 300 and 500 kilometers, or 186 and 311 miles, deep, according to two papers published today in the journal Science. - The white, red and brown hued jet streams surrounding the Great Red Spot are up to 3,000 km (1,800 mi) deep.

The intrigue: The roots of the storm extend below the cloud tops, and where, at least on Earth, sunlight warms the atmosphere and creates water vapor that rises, condenses and forms clouds and rain. - Jupiter then goes "beyond our simple ideas of water and sunlight being the only driver of weather. That was really surprising," says Scott Bolton of the Southwest Research Institute and principal investigator of the Juno mission.

Juno spotted two other vortex storms, but they aren't as deep. - "The Great Red Spot is not the only vortex storm that is breaking our rules," Bolton says.

What's not known: Whether the depth of the storm is changing over time, says Marzia Parisi of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. The big picture: The finding could help to answer a question that fascinates scientists: how has the storm persisted for centuries? - "Could we have a perpetual storm on Earth?" Parisi asks, adding the new data will help with modeling the longevity of storms and understanding the importance of land, which Jupiter lacks, in breaking up cyclones.

- "When we explain differences between Jupiter and Earth, we learn something about the Earth," Bolton says. "We have to modify ideas so Earth still works and Jupiter still works and explain the differences we observe."

|     | | | | | | A message from PL + US | | Opioid recovery starts with access to a paid national leave policy | | |  | | | | Addiction treatment and recovery groups, organizations and businesses urge Congress to pass a national paid leave program in the Build Back Better legislative package. The reason: This program would make treatment more accessible for 20 million Americans with substance use disorders. | | |  | | It'll help you deliver employee communications more effectively. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters. If you're interested in advertising, learn more here.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1300, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment