| | | | | | | Presented By PhRMA | | | | Axios Science | | By Alison Snyder · Nov 03, 2022 | | Thanks for reading Axios Science. This week's newsletter is 1,735 words, about a 6-minute read. | | | | | | 1 big thing: A tiny message from a hidden supermassive black hole |  | | | Illustration: Shoshana Gordon/Axios | | | | Scientists detected some of the tiniest particles in the universe and tracked them back to a supermassive black hole hidden out of Earth's view. Why it matters: Tiny neutrinos carry clues about some of the most energetic events in the universe — and are key to understanding the fundamental forces that govern it. - "They're interesting on both the largest and the smallest scales in nature," says Steven Prohira, a professor at the University of Kansas who studies ultra-high energy neutrinos.

- "Neutrinos are a bridge between what we know and what is just beyond what we understand."

How it works: The cosmic backdrop of neutrinos is thought to be mostly produced when cosmic rays — high-energy particles that travel through space at nearly the speed of light — smash into matter. Those collisions also create gamma rays, the highest-energy form of radiation. - The chargeless, almost massless neutrinos aren't deflected by magnetic fields and interact weakly with matter, so if they hit Earth as they race through the universe they point back to their source.

- They're a unique messenger but detecting them is difficult. "It's a really tough business — a heroic effort to do this," says Heino Falcke, a professor at Radboud University Nijmegen in the Netherlands who studies black holes.

- The IceCube neutrino detector at the South Pole uses more than 5,000 sensors buried 1 to 1.5 miles in the ice. When neutrinos hit molecules of ice they produce particles that emit blue light spotted by the sensors.

- Neutrinos and cosmic rays carry messages about their origins, which scientists have long sought. A leading candidate has been explosive gamma ray bursts.

Catch up quick: IceCube first detected an excess of 28 neutrinos from outside the Milky Way in 2013. - In 2018, a blazar (TXS 0506+056) was identified as the point of origin of a single neutrino. Blazars are active galaxies with a supermassive black hole at the center that produces a jet of ionized matter.

- The team then went back through nearly 10 years of IceCube data and found evidence of neutrinos coming from other active galaxies.

- "A pattern emerged but we weren't sure whether we were seeing fluctuations in the data or if this was real," says Francis Halzen, principal investigator of IceCube and a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

What's new: A combination of improvements — in calibrating the detector, improving the data analysis, gaining a better understanding of the ice and the use of machine learning — has confirmed the pattern was real, Halzen says. - In a study published today in the journal Science, the IceCube team reports evidence that the source of a stream of neutrinos detected between 2011 and 2020 can be traced back to the Messier 77 galaxy, or NGC 1068. (The statistical significance in the study isn't strong enough to qualify it as a discovery.)

- NGC 1068 is the second source of high-energy neutrinos found so far. The galaxy is about 47 million light-years from Earth.

The intrigue: At the center of NGC 1068 is an active galactic nucleus (AGN) fueled by a supermassive black hole hidden from Earth's view behind gas and dust. - "Of course, for neutrinos, there is no problem," Halzen says. "They get out of everything."

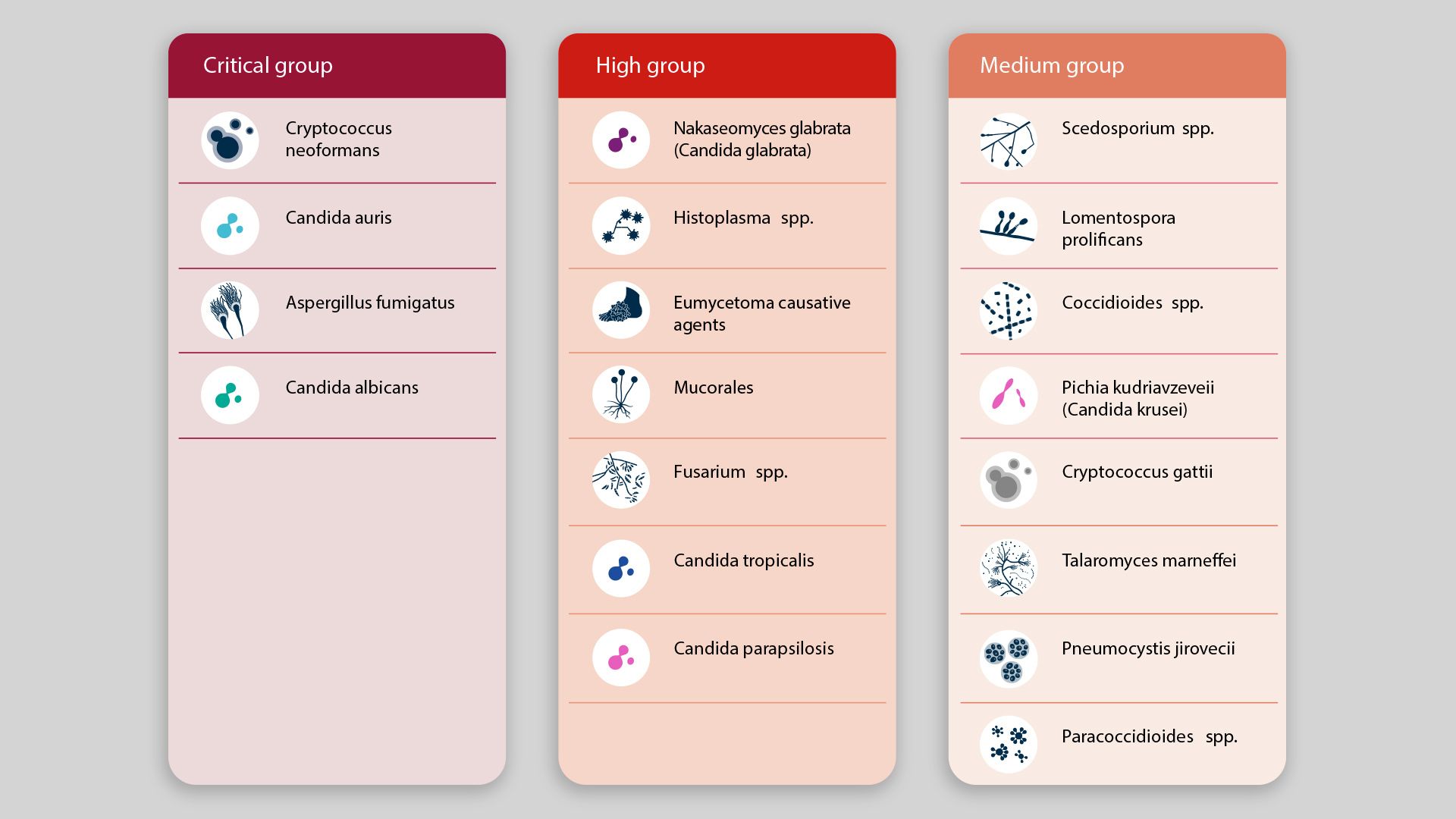

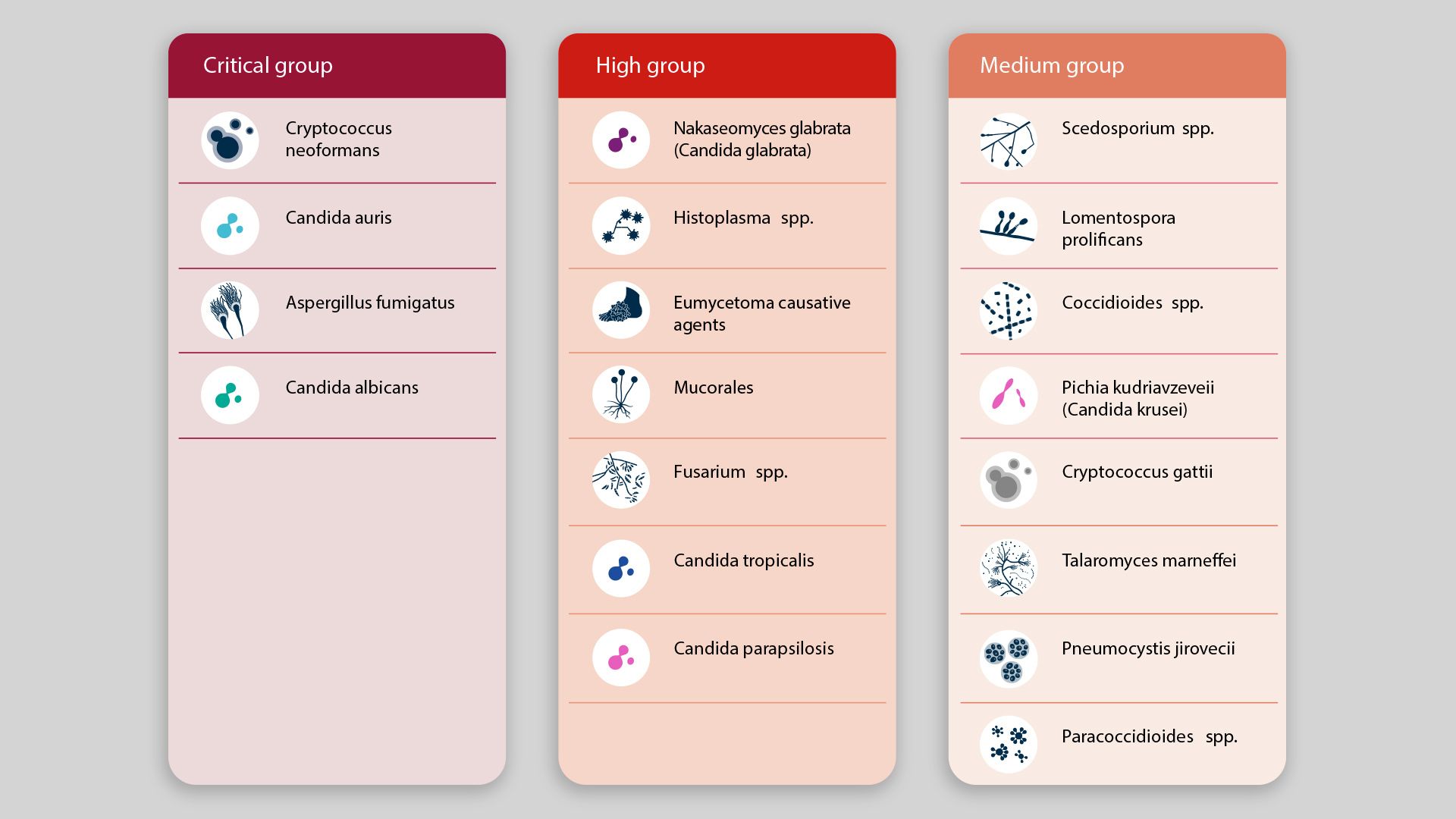

Go deeper. |     | | | | | | 2. Invasive fungi recognized as a global threat |  | | | Source: WHO's fungal priority pathogens list | | | | The dangers posed by growing outbreaks of opportunistic fungi that kill 1.6 million people globally every year require new drugs, diagnostics and surveillance programs, a CDC scientist tells Axios' Eileen Drage O'Reilly. Driving the news: The pandemic accelerated the rise of drug-resistant fungi in health care settings, and global warming has expanded the range of fungi growth in certain areas — problems flagged by the WHO, which released its first-ever list of dangerous fungi last week. What's happening: Fungi are "smart, tough organisms that are here to stay" and are evolving to take advantage of a growing immunocompromised population living in a world increasingly hospitable to certain pathogens due to climate change, says Tom Chiller, head of the CDC's Mycotic Disease Branch. Zoom in: "In recent years, the epidemiology has shifted. We've seen the emergence of new fungi that previously were not recognized as causes of human infections or rare cases that have now become more prominent, and also the emergence of antifungal drug resistant fungi," Cornelius Clancy, infectious disease doctor and professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh, tells Axios. - Chiller points to Candida, which is in our mouth, intestines and skin but can sometimes invade the bloodstream and cause sepsis and other complications. Over the past decade, though, Candida auris has become more drug resistant and shown new characteristics, Chiller says. "This is a Candida that's actually transmitting, from patient to hospital environment to patient. ... That was really a sea change for us."

- Another threatening development is seen in Sporothrix brasiliensis, a dimorphic fungus that usually exists in different forms as either a mold that can be infectious when it's in the outside world or as a yeast once it's inside a human or animal body and not infectious to others.

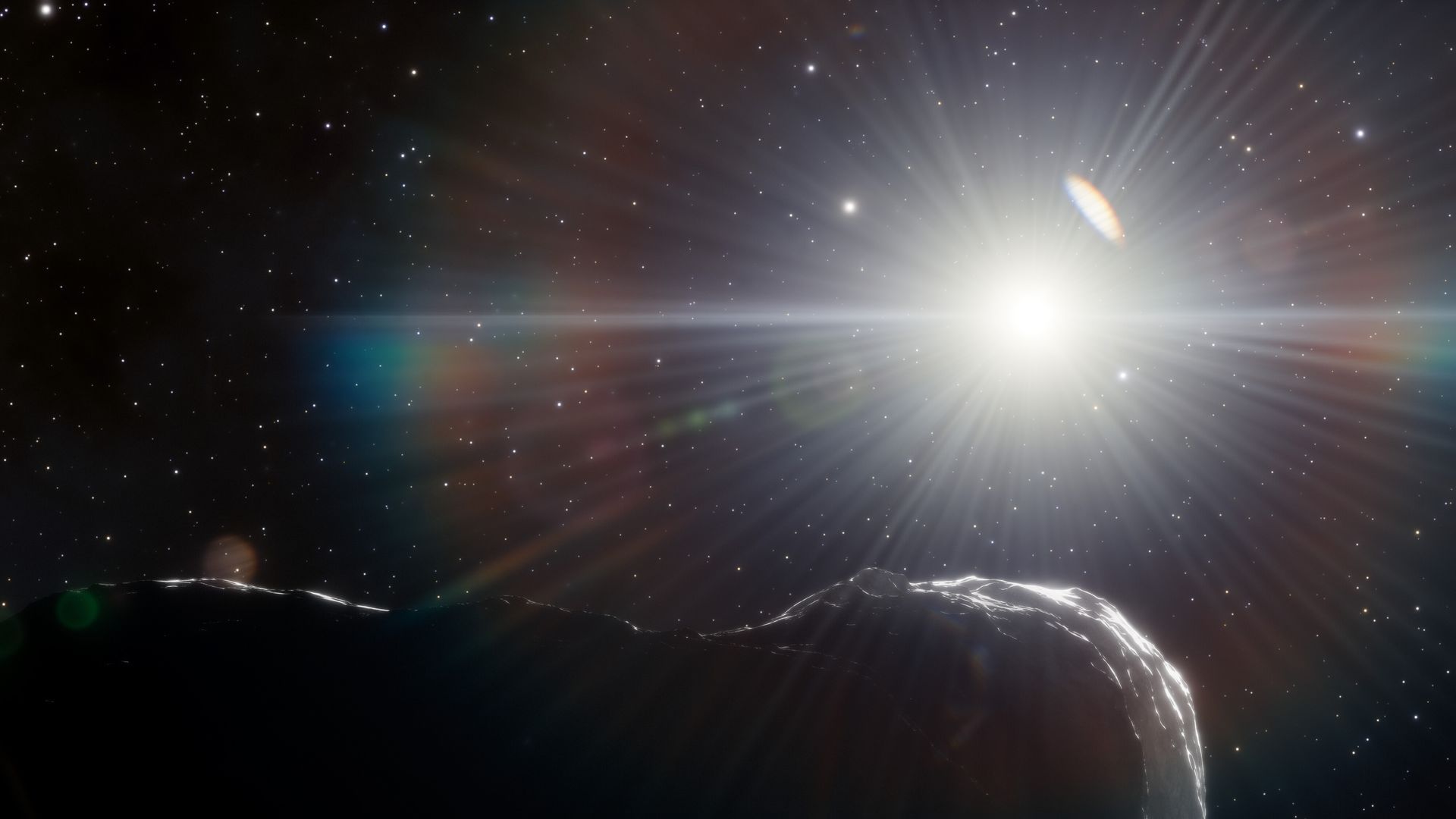

Between the lines: Humans and fungi are both eukaryotes, which makes it harder to target drugs for fungi without hurting human cells as well and complicates efforts to create diagnostics that can easily identify the difference. |     | | | | | | 3. "Planet killer" asteroid found in the glare of the Sun |  | | | Artist's illustration of an asteroid in the Sun's glare. Image: DOE/FNAL/DECam/CTIO/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/J. da Silva/Spaceengine | | | | Scientists have discovered a "planet killer" asteroid nearly a mile long within the orbits of Earth and Venus, Axios' Miriam Kramer writes. Why it matters: The space rock — named 2022 AP7 — poses no immediate threat to Earth, but its orbit crosses the planet's, making it an important object for scientists to keep an eye on in the future. What they found: 2022 AP7 is thought to be about 0.9 miles long — wide enough that if it hit Earth, a wide swath of the planet would feel the effects. - Details of the newfound asteroid and two others were first published in the Astronomical Journal and announced Monday in a news release.

- Scott Sheppard of the Carnegie Institution for Science, and an author of the study, stresses there is no evidence to suggest the asteroid will ever impact Earth, and even if it were to threaten the planet, that would happen thousands, if not millions of years in the future.

How it works: Researchers using the Dark Energy Camera in Chile discovered the space rock by observing during twilight — a crucial time for ground-based telescopes to find possibly dangerous asteroids usually lost in the glare of the Sun. - The part of the sky where 2022 AP7 was found is particularly challenging to search for asteroids within because astronomers only have two 10-minute windows each night for the survey of the area.

- "Our twilight survey is scouring the area within the orbits of Earth and Venus for asteroids," Sheppard said in the release. "So far we have found two large near-Earth asteroids that are about 1 kilometer across, a size that we call planet killers."

The big picture: NASA and other space agencies have been focusing on searching for and characterizing possibly hazardous asteroids for years. - Scientists think they've found most of the asteroids near Earth in the size range of 2022 AP7, but other, smaller yet still potentially devastating space rocks have gone undiscovered.

- "Less than half of the estimated 25,000 NEOs that are 140 meters and larger in size have been found to date," according to NASA.

|     | | | | | | A message from PhRMA | | Policymakers: It's time to advance solutions that address AMR | | |  | | | | The use of antibiotics to treat patients with non-confirmed bacterial infections gives bacteria the chance to mutate and resist the drugs made to kill them. The impact: This natural process known as antimicrobial resistance (AMR) ranks as a top 10 global public health threat. Get the facts. | | | | | | 4. Worthy of your time | | COP27 climate summit: what scientists are watching (Jeff Tollefson — Nature) Color is in the eye, and brain, of the beholder (Nicola Jones — Knowable) Rejoice in the end of daylight saving time (Katherine J. Wu — The Atlantic) |     | | | | | | 5. Reader postcards |  | | | Grizzly Giant, a giant sequoia in Yosemite National Park. (L) Photo: Kitty Boone; Redwoods in Henry Cowell Redwoods State Park, Calif. (R) Photo: Jack Baker | | | | There are some ancient tree fans among Axios Science readers... - Kitty Boone shared a photo she took of the Grizzly Giant, a giant sequoia in Yosemite National Park. "There is a reason the world loves them. They are 3,000 years old and so graceful… imagine what they have been around for in their lifetime," she writes.

- Jack Baker sent photos from California's Henry Cowell Redwoods State Park, where redwoods more than 1,500 years old stand about 270 feet tall — "wonderful!"

|     | | | | | | 6. Something wondrous |  | | | Príncipe Scops-Owl (Otus bikegila) Photo: Martim Melo | | | | An owl species found on the island of Príncipe is now named after a park ranger who has tracked and studied the birds for more than two decades. Why it matters: "If there is today the description of this new species, it is because of local knowledge and because of [park ranger] Bikegila in particular," Martim Melo from the Natural History and Science Museum at the University of Porto in Portugal said in an email. Details: The distinctiveness of the Príncipe Scops-Owl (Otus bikegila) was confirmed by its morphological features, the color and pattern of its plumage, DNA sequence data and the bird's song, Melo and his colleagues report this week in the journal ZooKeys. - The bird's song is "a unique, "tuu" note repeated at a fast rate of about one note per second, reminiscent of insect calls. It is often emitted in duets, almost as soon as the night has fallen," Melo said in a news release.

- "The song is the most diagnostic character," Melo says in an email. "Each species has its own, distinctive, call."

- Unlike songbirds that culturally transmit their songs, which can then change quickly, owls' songs are genetically determined, he explains. Differences in their songs indicate how long ago different species diverged.

The owl is named after Ceciliano do Bom Jesus, known as Bikegila, a former parrot harvester who is now a ranger in Príncipe Obô Natural Park. - Scientists first confirmed the owl in 2016, but Bikegila has tracked them since 1998. And "testimonies from local people suggesting its existence could be traced back to 1928," the authors write.

- Bikegila encountered the owls inside parrot nests — in tree holes often 65 feet to 100 feet off the ground — more than 20 years ago.

- The research represents "years of hard work," Melo says.

- "Bikegila and other local field assistants, such as co-author Sátiro da Costa, have a deep knowledge of the forest and on how to spend long periods inside it, removed from any contact with the outside world. Which is, of course, absolutely essential if we want to succeed."

What to watch: The researchers simultaneously published a paper about the ecology and conservation of the owl and proposed it be classified as "critically endangered." - An estimated 1,100 to 1,600 owls live only in a nearly 6 square mile section of rainforest in Príncipe Obô Natural Park, they write.

|     | | | | | | A message from PhRMA | | How to prepare against future public health threats | | |  | | | | Many disease-causing bacteria are constantly adapting to outsmart the medicines used to treat them through a process known as antimicrobial resistance (AMR). The challenge: Our current arsenal of medicines is inadequate to battle increasing rates of AMR. Learn about AMR solutions. | | | | Big thanks to Laurin-Whitney Gottbrath for editing this newsletter, to Shoshana Gordon on the Axios visuals team and to Carolyn DiPaolo for copy editing this edition. |  | | Are you a fan of this email format? It's called Smart Brevity®. Over 300 orgs use it — in a tool called Axios HQ — to drive productivity with clearer workplace communications. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters. If you're interested in advertising, learn more here.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment