| | | | | | | | | | | Axios Markets | | By Matt Phillips and Emily Peck · Aug 05, 2022 | | ⛱ It's here! Friday! We'll be off next week but Felix Salmon will still hit your inbox on Saturday. In the meantime, send in some fresh questions you'd like us to tackle when we're back. 🚨Before we go, we'll be watching for the unemployment report to see if the July jobs market held up. It's out later this morning, and Axios Macro is on it. Today's newsletter, edited by Kate Marino, is 1,155 words, 4.5 minutes. | | | | | | 1 big thing: Reader mailbag edition! |  | | | Illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios | | | | We recently asked readers to send questions they'd love to see us grapple with (keep 'em coming! Just reply to this email!). Here's a pithy query from Stephen Opler in Atlanta: - "Does the wave of inflation indicate that Modern Monetary Theory just wasn't sound?"

Why it matters: The left embraced MMT to say the government has been too squeamish about large deficits in recent years. They say the U.S. suffered weak growth and high unemployment as a result, Matt writes. How it works: MMT says countries like the U.S., which have their own currencies and central banks and repay debts in that currency, don't run out of money. The big picture: It's a simple premise, with big implications. - It means these governments don't need to raise taxes or borrow money to spend.

- Instead, they can — and indeed do — direct the central bank to create money they spend.

"We said the government's budget does not work like a household budget," Stephanie Kelton, an economics professor at Stony Brook University and a well-known MMT proponent, told Axios. - "If the votes are there, and Congress wants to authorize the spending of $500 billion, $1 trillion, $2 trillion, $5 trillion, Congress, via the power of the purse, has the capacity to spend money that it, quote-unquote, does not have."

Flashback: Since COVID struck, this theory was proven more or less correct. - Between early 2020 and 2021, Congress passed multiple bills that flooded the U.S. economy with roughly $5 trillion — but it didn't raise taxes to come up with the money.

- While the government technically raised funds in the bond market, the vast majority of those bonds ended up being purchased by the Federal Reserve, with freshly printed money.

The rub: Inflation. Yes, but: Others say inflation has damaged the policy proposals that emerged from MMT — which have tended to downplay the risks of running large deficits. - "One thing MMT tells you is that you shouldn't worry about debt and deficits," while de-emphasizing the risk that leads to inflation, says Michael Strain, director of economic policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute, a right-leaning think tank.

- "So in that sense, I think it is fair to say that MMT got it wrong."

The bottom line: The last two years revealed that MMT's basic ideas about how the financial plumbing of the Federal government works are essentially right. - Paul McCulley, the former chief economist of the giant asset manager Pimco, thinks proponents of MMT should lean into that victory. But keep the lessons of the current inflation in mind as well.

- "The description of the plumbing proved to be correct," he tells Axios.

- "The pandemic proved yes, it can be used in that way," he said. "We will stipulate that. But as a policy matter, it would not be wise to do this any longer."

|     | | | | | | 2. Catch up quick | | 📺 Merged HBO Max and Discovery+ streaming service to launch next summer. (Axios) ⚖️ Alex Jones ordered to pay $4 million to Sandy Hook parents. (Axios) 📝 Dems cut carried interest provision to secure Sinema's support. (Axios) |     | | | | | | 3. Oil drops below $90 a barrel |  Data: FactSet; Chart: Axios Visuals U.S. crude prices continue to tumble as stockpiles of oil and gas climb, Matt writes. Why it matters: Falling energy prices could help lower the next round of inflation readings, reducing pressure on the Federal Reserve to continue the rate-raising campaign that clobbered the stock market during the first half. Driving the news: U.S. benchmark West Texas Intermediate crude oil closed below $90 a barrel for the first time since February, before the Russian invasion of Ukraine set off a near crisis in global energy markets. - Recent reports from the Energy Information Administration showed rising stockpiles of oil and gasoline, hinting at a slowdown in demand.

- OPEC, the global oil cartel, also decided on Wednesday to boost production, albeit modestly.

- Benchmark gasoline futures prices are also down sharply this week. If sustained, that should ease prices at the pump (now averaging just over $4) in the coming weeks.

Yes, but: Goldman Sachs commodities analysts wrote in a recent note to clients: "The world is still facing a generalized energy shortage that spans the entire energy complex — from oil to natural gas and even to coal — due to both demand and supply factors that are unlikely to ease in the coming months." |     | | | | | | A message from Axios | | Equip your team with Axios Pro | | |  | | | | Axios Pro Corporate Subscriptions are here, with special pricing, dedicated account management and on-demand support for your employees. - Speak with our team, and we'll build you the best plan for your organization.

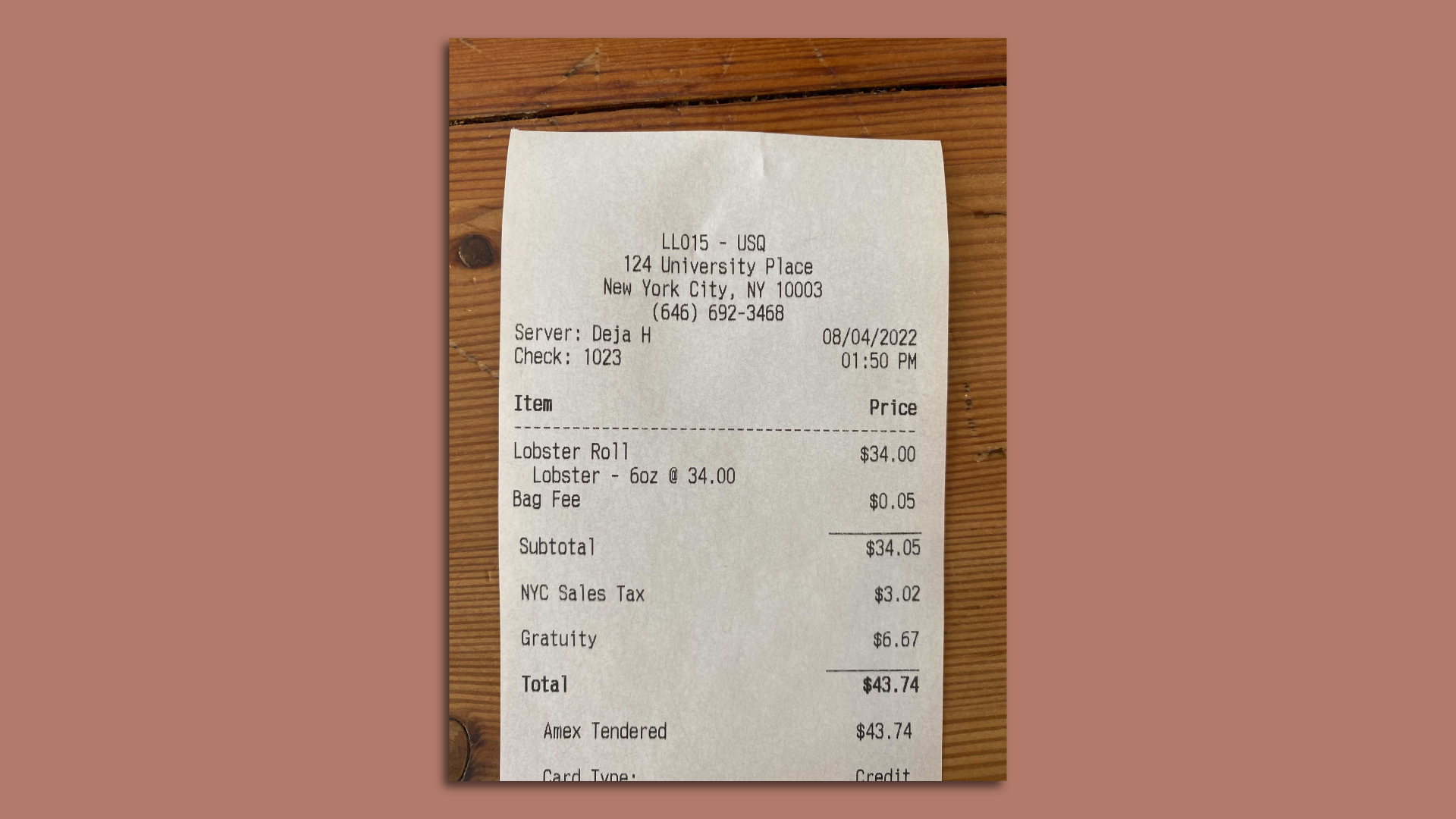

Learn more. | | | | | | 4. Stochastic lobsters |  | | | Photo: Felix Salmon/Axios | | | | On a hot August day, the lobster roll place across from the Axios office beckons temptingly, Axios' Felix Salmon writes. State of play: Reader, I caved. Doing so cost me $43.74, for a six-ounce sandwich, after tax and tip. Why it matters: Lobster prices are down this year, but lobster roll prices? Not so much. Instead, they increasingly seem to be generated by a random number machine. By the numbers: The benchmark lobster roll from The Clam Shack in Kennebunkport, Maine, is $29.95 this season. - At Nick's Lobster House in Brooklyn, the classic lobster roll is $22.

- In the Hamptons, prices range from $29 to $45.

- Manhatta, 60 stories above Lower Manhattan, sells a lobster roll with tarragon beurre blanc for $26.

- At the Grand Central Oyster Bar, the lobster roll is $38.95, with slaw and fries included.

- At Claws in West Sayville, New York, the standard roll is $29.95, but there are also options for a "double roll" for $57.95 or even a "triple roll" — "just obnoxious," per the menu — at $85.95.

The bottom line: When it comes to lobster rolls, there's no correlation between price and quality. But one thing is constant: Extracting lobster meat out of lobsters has never been easy. As a result, when labor costs go up, so do lobster roll prices. |     | | |  | | | | If you like this newsletter, your friends may, too! Refer your friends and get free Axios swag when they sign up. | | | | | | | | 4. Nerding out on mortgage rate data |  Data: MBA, Freddie Mac; Chart: Thomas Oide/Axios On Wednesday, the Mortgage Bankers Association said the rate on the average 30-year-mortgage was 5.43%. The very next day Freddie Mac said the rate was 4.99%. That's a big spread. At Felix's urging, Emily explains: What's happening: Timing. Even though they release the numbers just one day apart, the MBA data is almost a week older. It comes out Wednesday but covers the prior week ending Saturday. - Freddie's data covers the current week, looking at Monday through Wednesday and then coming out on Thursday.

- If you actually line up the dates covered, the rates are close together. (See the chart?)

Why it matters: It's a sign of a wild week, when markets changed their mind about what they think the Fed will do. Of note: Even when you line the dates up, Freddie's are typically lower than MBA's because of how Freddie calculates points, says Bankrate's Greg McBride. (Points are the upfront fees borrowers pay, sometimes in exchange for lower rates.) - MBA also includes data on rates for refinances; Freddie doesn't.

The bottom line: If you're in the market for a mortgage, these are just guideposts. You should shop around, McBride advises. "An average is an average." |     | | | | | | A message from Axios | | Equip your team with Axios Pro | | |  | | | | Axios Pro Corporate Subscriptions are here, with special pricing, dedicated account management and on-demand support for your employees. - Speak with our team, and we'll build you the best plan for your organization.

Learn more. | | | | ☀️ A big thank you to Mickey Meece for copy editing Markets today, and every day. |  | | Why stop here? Let's go Pro. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters. If you're interested in advertising, learn more here.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment