|

|  Hello Reader! This is the weekly email digest of Maria Popova's daily writings on The Marginalian (formerly Brain Pickings). If you missed last week's edition — every loss reveals what we're made of; David Whyte's poems of presence with wonder; Michael Pollan on the radical roots of the flying-witch broomstick — you can catch up right here. If you missed my very personal essay about the name-change, that is here. And if my labor of love enriches your life in any way, please consider supporting it with a donation — for more than fifteen years, it has remained free and ad-free and alive (as have I) thanks to reader patronage. If you already donate: THANK YOU. Hello Reader! This is the weekly email digest of Maria Popova's daily writings on The Marginalian (formerly Brain Pickings). If you missed last week's edition — every loss reveals what we're made of; David Whyte's poems of presence with wonder; Michael Pollan on the radical roots of the flying-witch broomstick — you can catch up right here. If you missed my very personal essay about the name-change, that is here. And if my labor of love enriches your life in any way, please consider supporting it with a donation — for more than fifteen years, it has remained free and ad-free and alive (as have I) thanks to reader patronage. If you already donate: THANK YOU.

|

To face the question of what makes us who we are with courage, lucidity, and fulness of feeling is to face, with all the restlessness and helplessness this stirs in the meaning-hungry soul, the elemental fact of our choicelessness in the conditions that lead to our existence. That is what the Nobel-winning founding father of quantum mechanics Erwin Schrödinger (August 12, 1887–January 4, 1961) addresses in some exquisite passages from My View of the World (public library) — the slender, daring deathbed book containing two long essays penned on either side of his Nobel Prize, thirty-five years apart yet united by the unbroken thread of his uncommon mind unafraid of its own capacity for feeling, that vital capacity for living fully into the grandest open questions of existence.  Erwin Schrödinger, circa 1920s. Schrödinger opens with one swift, awe-striking defense of what scientists dismiss as metaphysics — a realm of knowledge that lies beyond the current scientific tools and modes of truth-extraction, which history attests always reveals more about the limitations of the tools than about the limits of nature's truths. (Lest we forget, even so pure a form of physics as the hummingbird's flight was long considered a metaphysical phenomenon — that is, a yet-unsolved phenomenon explained as magic — until science fermented the technology of photography to capture the mechanics of the process.) Echoing Hannah Arendt's daring indictment that ceasing to ask unanswerable question would mean relinquishing "not only the ability to produce those thought-things that we call works of art but also the capacity to ask all the answerable questions upon which every civilization is founded," Schrödinger writes:  It is relatively easy to sweep away the whole of metaphysics, as Kant did. The slightest puff in its direction blows it away, and what was needed was not so much a powerful pair of lungs to provide the blast, as a powerful dose of courage to turn it against so timelessly venerable a house of cards. It is relatively easy to sweep away the whole of metaphysics, as Kant did. The slightest puff in its direction blows it away, and what was needed was not so much a powerful pair of lungs to provide the blast, as a powerful dose of courage to turn it against so timelessly venerable a house of cards.

But you must not think that what has then been achieved is the actual elimination of metaphysics from the empirical content of human knowledge. In fact, if we cut out all metaphysics it will be found to be vastly more difficult, indeed probably quite impossible, to give any intelligible account of even the most circumscribed area of specialisation within any specialised science you please. Metaphysics includes, amongst other things — to take just one quite crude example — the unquestioning acceptance of a more-than-physical — that is, transcendental — significance in a large number of thin sheets of wood-pulp covered with black marks such as are now before you… A real elimination of metaphysics means taking the soul out of both art and science, turning them into skeletons incapable of any further development.

Even as he made his reality-reconfiguring contributions to science and its search for fundamental truth, Schrödinger never relinquished his passionate curiosity about philosophy and the ongoing questions of meaning that kernel every truth in the flesh of consciousness. He was as drawn to Spinoza and Schopenhauer as he was to the ancient Eastern traditions, and especially in their untrammeled common ground of panpsychism — one of the oldest and most notoriously misunderstood theoretical models of consciousness in relation to the universe.  Total eclipse of the sun by Étienne Léopold Trouvelot. (Available as a print, as stationery cards, and as a face mask.) A century after the pioneering Canadian philosopher, psychiatrist, and nature-explorer Richard Maurice Bucke drew inspiration from Whitman to develop his theory of cosmic consciousness, and a century before the emerging science of counterfactuals threw its gauntlet at our fundamental assumptions about the nature of the universe, Schrödinger takes up the parallels between the discoveries of quantum physics and the core ideas of the Hindu philosophy of Vedanta. In what might best be described as an existentialist prose-poem, he invites you to imagine yourself seated on a mountain bench at sunset, beholding a transcendent display of nature:  Facing you, soaring up from the depths of the valley, is the mighty, glacier-tipped peak, its smooth snowfields and hard-edged rock-faces touched at this moment with soft rose-colour by the last rays of the departing sun, all marvellously sharp against the clear, pale, transparent blue of the sky. Facing you, soaring up from the depths of the valley, is the mighty, glacier-tipped peak, its smooth snowfields and hard-edged rock-faces touched at this moment with soft rose-colour by the last rays of the departing sun, all marvellously sharp against the clear, pale, transparent blue of the sky.

According to our usual way of looking at it, everything that you are seeing has, apart from small changes, been there for thousands of years before you. After a while — not long — you will no longer exist, and the woods and rocks and sky will continue, unchanged, for thousands of years after you. What is it that has called you so suddenly out of nothingness to enjoy for a brief while a spectacle which remains quite indifferent to you?

I see my soul reflected in Nature by Margaret C. Cook from a rare 1913 English edition of Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass. (Available as a print.) In a passage evocative of Whitman's timeless lines from "Crossing Brooklyn Ferry" — "Others will enter the gates of the ferry and cross from shore to shore… Others will see the islands large and small… A hundred years hence, or ever so many hundred years hence, others will see them… I am with you, you men and women of a generation, or ever so many generations hence … Just as you feel when you look on the river and sky, so I felt… Just as any of you is one of a living crowd, I was one of a crowd… What is it then between us?" — Schrödinger answers:  The conditions for your existence are almost as old as the rocks. For thousands of years men have striven and suffered and begotten and women have brought forth in pain. A hundred years ago, perhaps, another man sat on this spot; like you he gazed with awe and yearning in his heart at the dying light of the glaciers. Like you he was begotten of man and born of woman. He felt pain and brief joy as you do. Was he someone else? Was it not you yourself? What is this Self of yours? What was the necessary condition for making the thing conceived this time into you, just you and not someone else? What clearly intelligible scientific meaning can this 'someone else' really have? If she who is now your mother had cohabited with someone else and had a son by him, and your father had done likewise, would you have come to be? Or were you living in them, and in your father's father… thousands of years ago? And even if this is so, why are you not your brother, why is your brother not you, why are you not one of your distant cousins? What justifies you in obstinately discovering this difference — the difference between you and someone else — when objectively what is there is the same? The conditions for your existence are almost as old as the rocks. For thousands of years men have striven and suffered and begotten and women have brought forth in pain. A hundred years ago, perhaps, another man sat on this spot; like you he gazed with awe and yearning in his heart at the dying light of the glaciers. Like you he was begotten of man and born of woman. He felt pain and brief joy as you do. Was he someone else? Was it not you yourself? What is this Self of yours? What was the necessary condition for making the thing conceived this time into you, just you and not someone else? What clearly intelligible scientific meaning can this 'someone else' really have? If she who is now your mother had cohabited with someone else and had a son by him, and your father had done likewise, would you have come to be? Or were you living in them, and in your father's father… thousands of years ago? And even if this is so, why are you not your brother, why is your brother not you, why are you not one of your distant cousins? What justifies you in obstinately discovering this difference — the difference between you and someone else — when objectively what is there is the same?

[…] Inconceivable as it seems to ordinary reason, you — and all other conscious beings as such — are all in all. Hence this life of yours which you are living is not merely a piece of the entire existence, but is in a certain sense the whole.

Double rainbow from Les phénomènes de la physique, 1868. Available as a print and face mask. Once we fathom this fundamental reality of interbeing, Schrödinger observes, it becomes impossible to wish anything for ourselves that we do not wish for everyone else or to harm anyone else without harming ourselves:  It is the vision of this truth (of which the individual is seldom conscious in his actions) which underlies all morally valuable activity. It is the vision of this truth (of which the individual is seldom conscious in his actions) which underlies all morally valuable activity.

A decade later, in a lovely testament to Schrödinger's insistence on the indivisibility of science and art in addressing those grandest unanswered question, Iris Murdoch — one of the vastest minds and finest literary artists of her time, and of all time — captured this elemental truth in her case for art as "an occasion for unselfing," observing:  The self, the place where we live, is a place of illusion. Goodness is connected with the attempt to see the unself… to pierce the veil of selfish consciousness and join the world as it really is. The self, the place where we live, is a place of illusion. Goodness is connected with the attempt to see the unself… to pierce the veil of selfish consciousness and join the world as it really is.

Complement this fragment of Schrödinger's My View of the World — a superb read in its slim totality — with the poetic physicist Alan Lightman on selfhood, mortality, and what makes life worth living, then revisit Alan Watts — who introduced the Western mind to Vedanta and its consonance with "the new physics" of the quantum world — on the self, the universe, and becoming who we really are. donating=lovingFor a decade and half, I have been spending hundreds of hours and thousands of dollars each month composing The Marginalian (formerly Brain Pickings). It has remained free and ad-free and alive thanks to patronage from readers. I have no staff, no interns, no assistant — a thoroughly one-woman labor of love that is also my life and my livelihood. If this labor makes your own life more livable in any way, please consider lending a helping hand. Your support makes all the difference.monthly donationYou can become a Sustaining Patron with a recurring monthly donation of your choosing, between a cup of tea and a Brooklyn lunch. | | one-time donationOr you can become a Spontaneous Supporter with a one-time donation in any amount. |  | |  |

|

| Partial to Bitcoin? You can beam some bit-love my way: 197usDS6AsL9wDKxtGM6xaWjmR5ejgqem7 Need to cancel an existing donation? (It's okay — life changes course. I treasure your kindness and appreciate your support for as long as it lasted.) You can do so on this page. |

|

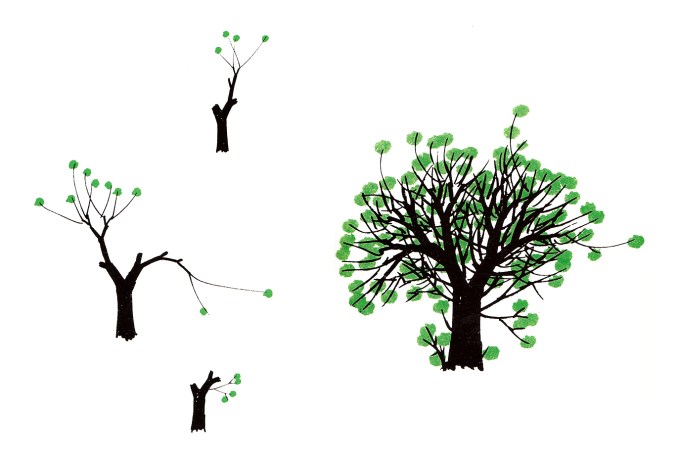

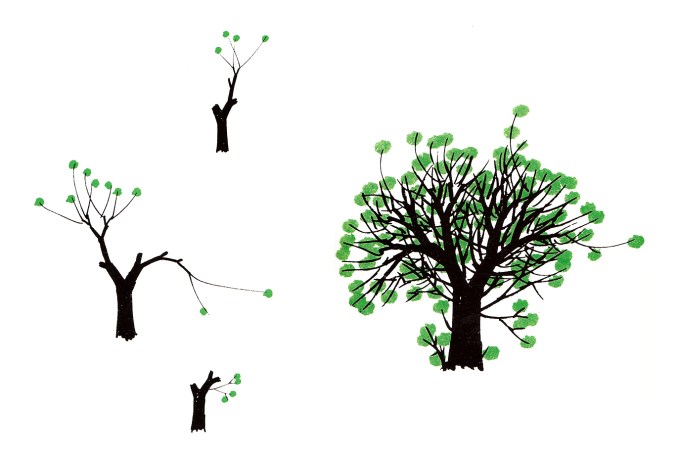

Few things salve sanity better than the awareness that there are infinitely many kinds of beautiful lives, and few places foster this awareness more readily than the forest — this cathedral of infinite possibility, pillared by trees of wildly different shapes and sizes that all began life as nearly identical seeds. Among the many existential consolations of trees — these teachers in loss as a portal to revelation, these high priestesses of optimism, these virtuosi of improvisation, these emissaries of eternity — is how they self-sculpt their beauty and character from the monolith of challenge that is life. Once planted in its chance-granted location, each tree morphs the basic givens of its genome into a singular shape in response to the gauntlets of its environment: It boughs down low to elude the unforgiving wind, rises and bends to reach the sunlit corner of the umbral canopy, grows a wondrous sidewise trunk to go on living after lightning. This endless, life-affirming dialogue between a tree's predestined structure and its living shape is what the visionary Italian artist, designer, inventor, futurist, and visual philosopher Bruno Munari (October 24, 1907–September 30, 1998) explores in the spare, splendid 1978 gem Drawing a Tree (public library). Inspired by Leonardo da Vinci's centuries-old diagrammatic study of tree growth, this unexampled masterpiece is a work of visual poetry and existential philosophy in the guise of a simple, elegant drawing guide to the art of trees rooted in their science.  Leonardo da Vinci's diagram of tree growth. Munari — who made some wildly inventive "interactive" picture-books before the Internet was born and who saw graphic literacy as the bridge "between living people and art as a living thing" — annotates the drawing lesson with his spare, poetic prose, contouring the life of a tree:  At last winter is finished and, from the ground where a seed has dropped, a vertical green blade appears. The sun starts to make itself felt and the green shoots grow. It is a tree, but so small no one recognizes it yet. Little by little it grows tough. It begins to branch, buds germinate on its branches, other branches spring from the buds, other leaves from the branches, and so on. A few years later, that green blade will have become a fine trunk covered in boughs. Later still, it will have produced wide branches which will produce leaves, blossoms and fruit. In autumn it will spread its seeds around, and some will fall beneath it while others will be carried far away by the wind. At last winter is finished and, from the ground where a seed has dropped, a vertical green blade appears. The sun starts to make itself felt and the green shoots grow. It is a tree, but so small no one recognizes it yet. Little by little it grows tough. It begins to branch, buds germinate on its branches, other branches spring from the buds, other leaves from the branches, and so on. A few years later, that green blade will have become a fine trunk covered in boughs. Later still, it will have produced wide branches which will produce leaves, blossoms and fruit. In autumn it will spread its seeds around, and some will fall beneath it while others will be carried far away by the wind.

Almost everywhere a seed falls, a new tree will grow.

Writing while elsewhere in Europe a refugee was revolutionizing the mathematics of reality with the discovery of fractals — a new science that would come to explain everything from earthquakes to economics markets, most readily visible in nature in trees — Munari deduces a basic growth pattern all trees share: each branch splitting into newer branches, each slenderer than its progenitor.

If they grew in isolation, free from any environmental challenge, all trees would follow perfectly predictable fractal geometries — a pattern so simple anyone could draw it, yet an ideal form not found in nature. This is where the existential meets the scientific and the artistic. Munari observes:  To grow so exactly, a tree would have to live in a place where there was no wind and with the sun always high in the sky, with the rain always the same and with constant nourishment from the ground all the time. There would have to be no lightning flashes nor even any spar changes in temperature, no snow or frost, never too hot or dry. To grow so exactly, a tree would have to live in a place where there was no wind and with the sun always high in the sky, with the rain always the same and with constant nourishment from the ground all the time. There would have to be no lightning flashes nor even any spar changes in temperature, no snow or frost, never too hot or dry.

Because no such idyllic conditions exist in reality, Munari draws the tree as versions of the pattern adapted to various challenges. (Yes. There are infinitely many kinds of beautiful lives.)

Delighting in the wildest subversions of the pattern — "there are the mad branches too, like in nearly all families" — Munari observes that even through them, you can still discern the fundamental form if you look attentively enough.

Drawing on the long human tradition of seeing ourselves in trees, Munari offers a tender reminder that trees — like us — take their shape and sculpt their individual character in the act of healing from hurt:  Here we are at the point where the sky turns dark and a real and proper storm comes, the tree waves frantically in the wind, as if it were afraid. A flash of lightning from the almost black sky hits the tree and disappears in a blaze of light. Through the heavy rain you can see a part of the tree on the ground, a big limb with its smaller branches. All you can hear is the sound of the heavy rain on the leaves. Here we are at the point where the sky turns dark and a real and proper storm comes, the tree waves frantically in the wind, as if it were afraid. A flash of lightning from the almost black sky hits the tree and disappears in a blaze of light. Through the heavy rain you can see a part of the tree on the ground, a big limb with its smaller branches. All you can hear is the sound of the heavy rain on the leaves.

The next year the tree is different, wounded. New branches still shoot out though, as if nothing has happened. This is how trees change shape: a flash of lightning, the weight of the snow on the branches, insects that gnaw at the wood… and the tree changes shape.

As he draws "some hurt and wounded trees," Munari observes that you can still see the contours of their elemental structure through their scars and healing adaptations.

In an oak leaf's "network of nerves," he finds a miniature of the entire tree's branching pattern. (This resemblance, of course, is what fractals explain — the leaf at the tip of the branch at the side of the trunk is just the finest extension of the fractal structure.)

Munari goes on to draw variations on the basic tree-growth pattern in different species, and variations on each species' adaptation of the pattern in different specimens.

Exactly two centuries after William Blake issued his searing indictment of inattention and numbness to life — "The tree which moves some to tears of joy is in the eyes of others only a green thing which stands in the way… As a man is, so he sees." — what emerges from the pages of Munari's little, largehearted book is an invitation to look at green things more intimately as training ground for loving the world and its variousness more joyously.

Complement Drawing a Tree with Japanese artist Hasui Kawase's stunning woodblock prints of trees and some equally, differently stunning drawings of trees by indigenous Indian artists, then revisit Munari's delightful visual-anthropological guide to Italian hand-gestures. For a contemporary counterpart of existential-processing-disguised-as-drawing-lessons, dive into my friend Wendy MacNaughton's wondrous DrawTogether project for human saplings.

When Matthew Burgess was an eleven-year-old already feeling other in the suburban Southern California of his childhood — long before he became a poet and a public school art teacher, before he made a bicontinental home in Brooklyn and Berlin with his husband — he was captivated by a tiny bright-spirited rainbow on a postage stamp that appeared on the television show The Love Boat. It was the now-iconic 1985 USPS Love stamp — a miniature of the largest copyrighted artwork in the world: the colossal rainbow swash painted on a Boston gas storage tank in 1971 by Corita Kent (November 20, 1918–September 18, 1986) — the radical nun, artist, teacher, social justice activist, and long-undersung pop art pioneer, who inspired generations of makers with her 10 rules for learning and life, collaborated frequently and dazzlingly with poets, believed that "the person who makes things is a sign of hope," and made her art and her life along the vector of this belief. This sentiment — the most precise and poetic summation of Sister Corita's credo — is the epigraph that opens Burgess's loving picture-book biography Make Meatballs Sing: The Life and Art of Corita Kent (public library), created in collaboration with the Corita Art Center and illustrated by artist Kara Kramer with patterned, textured, sensitive vibrancy consonant with Corita's art spirit and sensibility.

Doing and making are acts of hope, and as that hope grows we stop feeling overwhelmed by the troubles of the world. We remember that we — as individuals and groups — can do something about those troubles. Doing and making are acts of hope, and as that hope grows we stop feeling overwhelmed by the troubles of the world. We remember that we — as individuals and groups — can do something about those troubles.

Emerging from these tender pages is an activist who devoted her life to fighting with fierce gentleness and generosity of soul for justice and peace in every form, from civil rights to nuclear disarmament; a rebel who subverted commerce for creativity, turning a corporate slogan (for Del Monte tomato sauce) into a clarion call for the the power of art to constellate the ordinary with wonder (which lent the book its title); a visionary who subverted the outdated dogmas of the very institution she served to effect landmark reform within the Catholic Church and to engage the secular world with the creative life of the soul; a teacher who helped her students overcome the self-consciousness and overthinking that stifle creativity by fusing play and work through her quirkily titled, ingeniously deployed process of PLORKing; an artist who became a patron saint of noticing, of paying closer attention to the world as the only means of loving it more fully — something Corita herself captured in an essays on art and life:  Poets and artists — makers — look long and lovingly at commonplace things, rearrange them and put their rearrangements where others can notice them too. Poets and artists — makers — look long and lovingly at commonplace things, rearrange them and put their rearrangements where others can notice them too.

We meet Corita before she was Corita — little Frances Elizabeth Kent, growing up in Iowa, full of warm and wakeful wonder at the world — and we see her discover art as a portal of connection to this living, loving world.

And then, at eighteen, Frances astonishes everyone in her world with the decision to join the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart, becoming Sister Mary Corita Kent.

We watch her learn art history from the elder nun heading the Immaculate Heart art department and learn screen-printing from the Mexican printmaker María Sodi de Ramos Martínez, to whom one of Corita's students had introduced her.

We see her transform the annual Mary's Day religious procession into a community festival welcoming believers and the rest of us alike.

We see her teach kids the power of art to magnify happiness, and we see her use that power to stand up for the civilizational foundations of happiness — peace and justice — with her own art.

We leaf through the decades of her extraordinary life as she presses against the status quo in every guise with the gentle paint-stained hand of art and love: There she is, yielding protest signs with a radiant smile; there she is, on the cover of Newsweek as a modern hero of art and justice, earning her nation's affection and her Archbishop's wrath.

And then, astonished again, we watch her make the decision at age fifty to leave the church, move to Boston, and devote herself fully to art and activism.

There, she paints her colossal rainbow of love; there, she makes her iconic love your brother print shortly after the assassination of Dr. King.

Curiously, delightfully, Burgess did not arrive at the idea for this tribute of a book through his childhood encounter with Corita's art. In a touching testament to the breadth of Corita's creative ecosystem, he arrived at it through a sidewise strand unspooling from his debut children's book, also a picture-book biography of one of his artistic heroes — the wondrous Enormous Smallness: A Story of E. E. Cummings. Upon its publication, Burgess learned from his cousin's partner — a historian then working on a retrospective of Corita's work at the Harvard Art Museum — that Corita had greatly admired Cummings and incorporated lines from his poems into her prints. (It is hardly surprising that a woman of such countercultural courage and fierce daring found resonance with the poet who had built his own life upon the credo that "to be nobody-but-yourself — in a world which is doing its best, night and day, to make you everybody else — means to fight the hardest battle which any human being can fight.") "Down the rabbit hole I happily tumbled," Burgess recounts of immersing himself in the wonderland of Corita's world — and so the book was born.

Couple Make Meatballs Sing with Burgess's equally loving picture-book biography of another of his artistic heroes — Drawing on Walls: A Story of Keith Haring — then revisit this ever-growing reliquary of excellent picture-book biographies of cultural heroes. Illustrations by Kara Kramer courtesy of Enchanted Lion Books. Photographs by Maria Popova. donating=lovingFor a decade and half, I have been spending hundreds of hours and thousands of dollars each month composing The Marginalian (formerly Brain Pickings). It has remained free and ad-free and alive thanks to patronage from readers. I have no staff, no interns, no assistant — a thoroughly one-woman labor of love that is also my life and my livelihood. If this labor makes your own life more livable in any way, please consider lending a helping hand. Your support makes all the difference.monthly donationYou can become a Sustaining Patron with a recurring monthly donation of your choosing, between a cup of tea and a Brooklyn lunch. | | one-time donationOr you can become a Spontaneous Supporter with a one-time donation in any amount. |  | |  |

|

| Partial to Bitcoin? You can beam some bit-love my way: 197usDS6AsL9wDKxtGM6xaWjmR5ejgqem7 Need to cancel an existing donation? (It's okay — life changes course. I treasure your kindness and appreciate your support for as long as it lasted.) You can do so on this page. |

|

A SMALL, DELIGHTFUL SIDE PROJECT: AND: I WROTE A CHILDREN'S BOOK ABOUT SCIENCE AND LOVE | |

| |

Hello Reader! This is the weekly email digest of Maria Popova's daily writings on

Hello Reader! This is the weekly email digest of Maria Popova's daily writings on

It is relatively easy to sweep away the whole of metaphysics, as Kant did. The slightest puff in its direction blows it away, and what was needed was not so much a powerful pair of lungs to provide the blast, as a powerful dose of courage to turn it against so timelessly venerable a house of cards.

It is relatively easy to sweep away the whole of metaphysics, as Kant did. The slightest puff in its direction blows it away, and what was needed was not so much a powerful pair of lungs to provide the blast, as a powerful dose of courage to turn it against so timelessly venerable a house of cards.

No comments:

Post a Comment