| | | | | | | Presented By Blue Cross Blue Shield Association | | | | Axios Science | | By Alison Snyder ·Jul 29, 2021 | | Thanks for reading Axios Science. This week's newsletter is 1,644 words, a 6-minute read. | | | | | | 1 big thing: The genome's uncharted territories |  | | | Illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios | | | | Scientists have now drafted a complete version of the human genome sequence — but the job of deciphering our DNA has only just begun, Eileen and I write. Why it matters: The bulk of the human genome is noncoding regions, some of which play an important role in how genes are expressed. New tools are allowing scientists to test exactly how these elements — once called "junk DNA" — work, which could lead to new drug targets. Driving the news: A team of 99 scientists completed the human genome sequence last week, filling in gaps in the draft sequence published 20 years ago using some new technologies. - They reported the human genome is 3.05 billion base pairs long and consists of 19,969 protein-coding genes, including more than 100 newly deciphered genes that can likely produce proteins.

- The completed genome sequence also now has 189 million base pairs of large swathes of highly repetitive DNA that doesn't encode for genes, including 5.5 million base pairs of newly discovered DNA repeats.

- These and other noncoding DNA have been ignored over the past two decades, says Karen Miga, a genomics researcher at the University of California, Santa Cruz who co-founded the consortium of scientists who completed the sequence.

The big picture: Scientists have known for decades that the bulk of the human genome — roughly 98% — doesn't encode the genes for proteins that power biology and also underlie disease when their function is altered. - Instead, some of these noncoding regions likely regulate whether genes are on or off or alter their activity — roles that researchers are now trying to test.

- They're also trying to understand how these elements vary between individuals and how they guide the course of a disease or what treatments might be effective.

Zoom in: Tools like the gene editor CRISPR are allowing researchers to test the roles of noncoding DNA in specific diseases or disorders. 1) The course of a cancer or the effectiveness of treatment for it may be affected by different types of noncoding RNA. 2) Limb and head formation during human development may also be guided by the noncoding genome. 3) A new therapy for sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia, which affect hemoglobin in red blood cells, acts on a noncoding part of the genome. The challenge: With coding regions of the genome, scientists can see the effects of changing a base pair of DNA in the protein it forms. - "In noncoding regions, we don't have a similar Rosetta Stone to translate," says Neville Sanjana, who studies genomics at New York University and the New York Genome Center and whose research underpins the sickle cell anemia therapy.

- That's why tools like CRISPR are necessary but he says they'll need to be improved and combined with single-cell technologies to screen the massive noncoding genome and understand the network of genes it regulates.

What to watch: Gene editing can cause unwanted edits, or "off-target effects," often in the noncoding portion of the genome. - Hsieh says those effects can't be assumed harmless in the long run — and is another reason it's important to determine the functions of the noncoding regions.

The bottom line: "We need to understand how these regions change or vary between individuals in the human population, and how that organization influences genome regulation and function," Miga says. |     | | | | | | 2. Urban landscaping to blame in prolonged allergy season |  | | | Illustration: Shoshana Gordon/Axios | | | | Allergy season in North America has been the lengthiest and the most severe in decades, and experts say the millions of disproportionately male trees planted in urban areas are partly to blame for high pollen counts, Axios' Marisa Fernandez reports. Why it matters: Prolonged exposure to pollen is disrupting the lives of an increasing number of people who are developing allergies that can lead to lifelong treatments for respiratory problems. Threat level: Pollen counts are greatly affected by the "botanical sexism" found in urban landscaping, horticulturist Tom Ogren tells Axios. - Trees that have male reproductive organs are preferred in areas because they don't drop messy seed pods or fruit, but instead, release pollen at certain times during the year.

- When female trees, which capture pollen, are nearly non-existent, landscaped areas can be overrun by mass amounts of pollen in the air.

What's happening: Immediate symptoms of tree pollen allergies include rhinitis, conjunctivitis, hay fever, allergic-asthma, dermatitis and even anaphylactic shock. - Longer-term, it could lead to the need to treat asthma, chronic sinusitis, upper respiratory infection, nasal congestion or sleep-disordered breathing.

The big picture: Pollen season has increased by 20 days annually between 1990 and 2018, while pollen concentrations in North America increased 21% over the same time period, a recent study found. - A study published last month found male trees and shrubs studied as early as 1998 have inundated cities and contributed to the overall allergy index in the U.S. by about 6%, with increases as great as 20% in Casper, Wyoming, and by nearly 15% in Minneapolis.

- Warming temperatures and extreme weather due to climate change, pollution and excess carbon dioxide in the air have exacerbated this issue by lengthening the pollen-producing season.

What to watch: Some cities like Albuquerque and Berkeley have made pledges or created pollen control ordinances that require a better ratio in male-to-female planting or only require female trees. |     | | | | | | 3. Catch up on COVID-19 |  | | | Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios | | | | The surge in COVID-19 cases is strengthening the case for more frequent testing, Axios' Bryan Walsh writes. A billion-dollar debate about booster shots is unfolding as Pfizer released data suggesting its COVID-19 vaccine's efficacy diminishes over time, Axios' Bob Herman reports. Vaccine mandates were announced this week by state governments, private businesses and part of the federal government, Axios' Caitlin Owens writes. The CDC issued new mask guidance saying vaccinated people in COVID-19 hotspots should again wear masks in public, indoor settings, per Marisa. |     | | | | | | A message from Blue Cross Blue Shield Association | | Using data to build vaccine confidence | | |  | | | | Reluctance about vaccines tends to be higher in communities of color due to a long history of inequitable health treatment. Learn how we are using Blue Cross and Blue Shield data to identify social vulnerabilities and replace hesitancy with hope. | | | | | | 4. NASA's Perseverance rover gets busy on Mars |  | | | Mars seen by Perseverance. Photo: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASU/MSSS | | | | NASA's Perseverance rover on Mars is about to collect its first rock sample from the Red Planet, Axios' Miriam Kramer reports. Why it matters: The space agency wants to send a future mission to collect that sample and other Perseverance caches for a return to Earth where they can be analyzed by high-powered tools. Details: Some of these samples are expected to be chosen because they may contain preserved signs of ancient life within them, but this first sample likely won't. - "While the rocks located in this geologic unit are not great time capsules for organics, we believe they have been around since the formation of Jezero Crater and [will be] incredibly valuable to fill gaps in our geologic understanding of this region — things we'll desperately need to know if we find life once existed on Mars," Perseverance project scientist Ken Farley, of Caltech, said in a statement.

- NASA expects Perseverance will collect its sample within the next couple of weeks and it will do some reconnaissance work to make sure the rover is gathering exactly the kind of sample scientists are hoping for on this first go.

How it works: As part of Perseverance's survey of the area, the rover will take detailed images so that mission managers can pick a geological target similar to the one they want to sample and use it as additional data for studying the sample they extract. - Once survey and analysis are done, Perseverance will take a Martian day to charge its battery and then collect and store the sample.

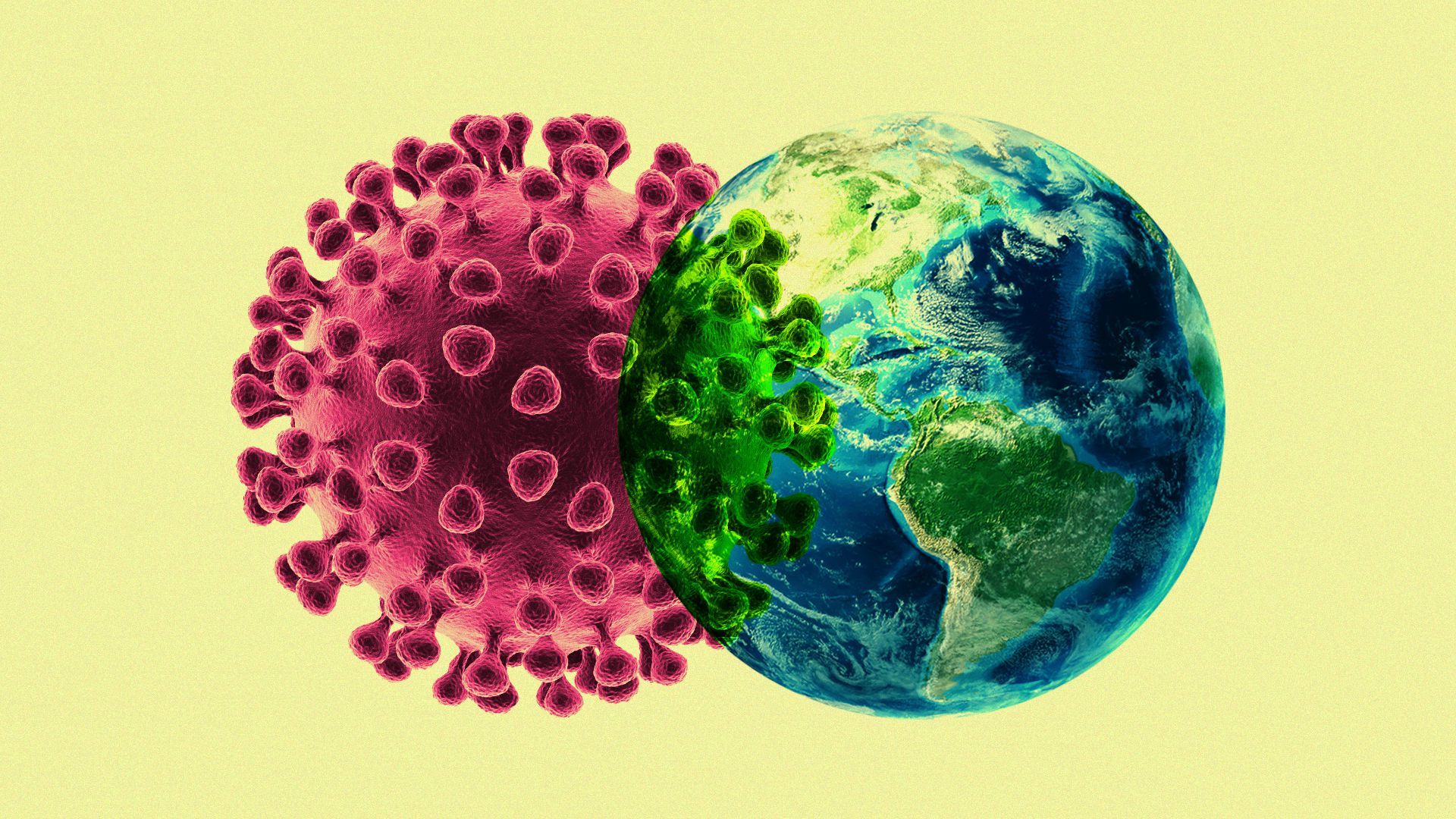

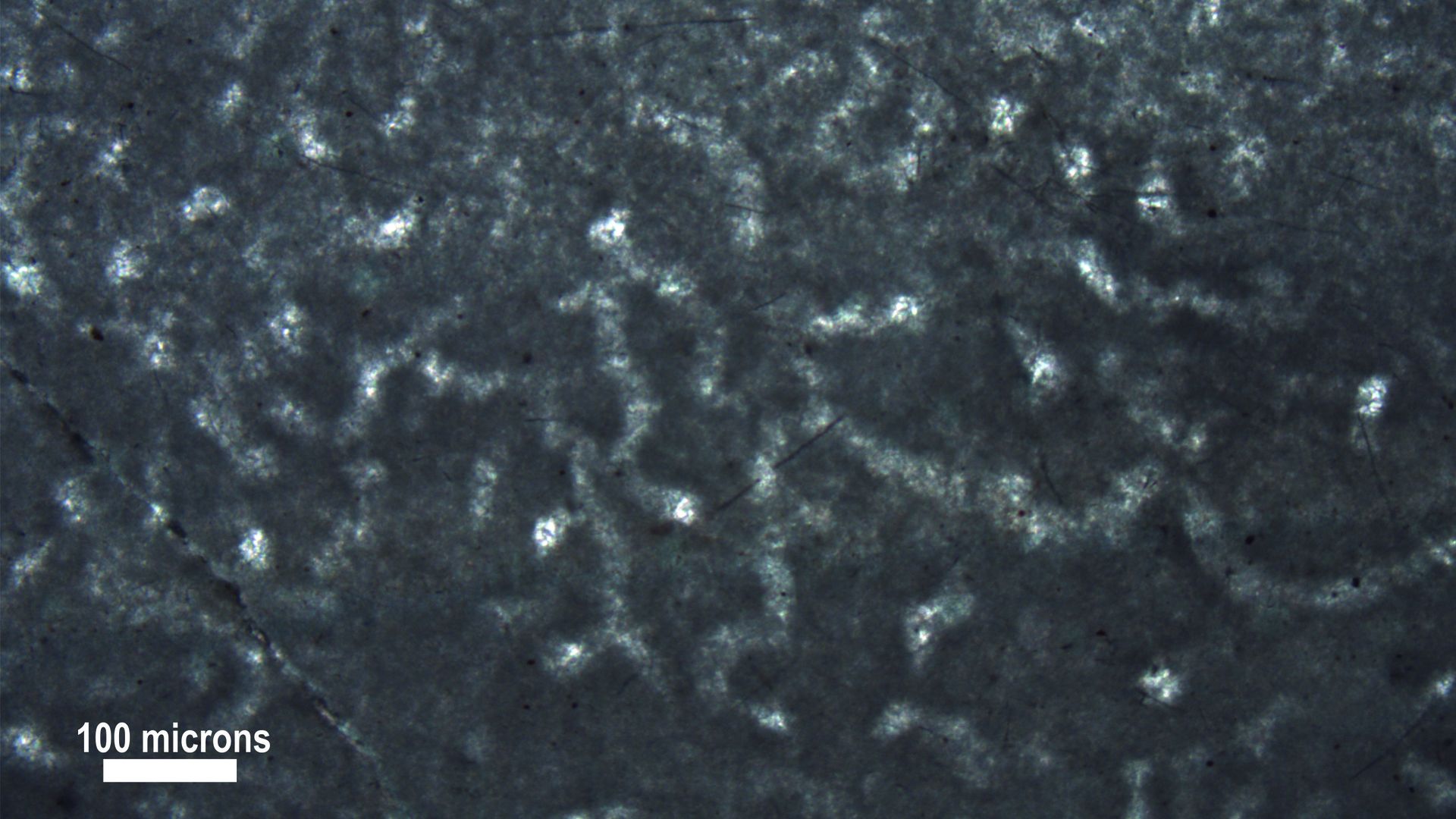

|     | | | | | | 5. Worthy of your time |  | | | Illustration: Shoshana Gordon/Axios | | | | Australian wildfires had bigger influence on climate than lockdowns (Andrew Freedman — Axios) How trust in science can make you vulnerable to 'pseudoscience' (Robert Preidt — U.S. News and World Report) Learning to live in Steven Weinberg's pointless universe (Dan Falk — Scientific American) What animals see in the stars, and what they stand to lose (Joshua Sokol — NYT) |     | | | | | | 6. Something wondrous |  | | | A microscope image of the wormlike structures. Credit: E.C. Turner/ Nature 2021 | | | | A meshlike network of tubes etched in 890-million-year-old rock may be evidence of early sea sponges, a new paper claims — with some controversy. Why it matters: The fossil, if confirmed to be the mark of sea sponges, would represent the earliest record of animal life on Earth by far — and suggest animals emerged on the planet before oxygen reached a level considered essential for them to thrive. - The oldest undisputed sponge fossils to date are from about 540 million years ago at the beginning of the Cambrian Period, when most of the animal groups on Earth today emerged from a burst of evolution.

What was found: Geologist Elizabeth Turner of Laurentian University in Ontario discovered rocks in Little Dal reefs — an area of northwestern Canada once submerged in water — containing wormlike tubes similar in size, shape and branching to the skeletons of modern sponges. Yes, but: The possible fossils lack spicules, or mineralized skeletal parts, characteristic of some sponges. - Turner writes in the paper published this week in Nature that focusing on spicules overlooks the possibility of protein skeletons similar to those found in some modern sponges.

- The record of Earth's oceans at the time also suggests there wasn't enough oxygen to support life until something known as the Neoproterozoic Oxygenation Event 800 million to 540 million years ago.

- But sponges may have been able to live in pockets of the reefs if photosynthetic bacteria nearby released enough oxygen, Turner suggests.

What they're saying: Some scientists say the finding is in line with genomic data suggesting modern-day sponges could have emerged as early as one billion years ago. - But skeptics say there may be other explanations for the patterns — microbes or crystals — and if sponges did emerge 890 million years ago, they would have proliferated on Earth.

- Turner's explanation: Sponges may have been limited to their low-oxygen environment for millions of years until oxygen became more abundant and sponges more ubiquitous, she told Smithsonian Magazine.

The big picture: "Everything on Earth has an ancestor," Roger Summons, an MIT geobiologist who was not involved in the research, told the AP. - "It's always been predicted that the first evidence of animal life would be small and cryptic, a very subtle clue."

|     | | | | | | A message from Blue Cross Blue Shield Association | | Making health coverage more affordable | | |  | | | | Enhanced premium assistance that makes health care coverage more affordable will end in 2022. See how Congress can help millions of middle class families by expanding access, reducing costs and making health care more equitable for everyone. | | |  | | It'll help you deliver employee communications more effectively. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters. If you're interested in advertising, learn more here.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1300, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment