| | | | | | | Presented By University of Nebraska Medical Center | | | | Axios Science | | By Alison Snyder ·Jun 03, 2021 | | Thanks for reading Axios Science. This week's newsletter — about HIV research, pandemic preparations, puppy social skills and more — is 1,859 words, a 7-minute read. - Send your feedback and ideas to me at alison@axios.com. You can reach Eileen Drage O'Reilly at eileen@axios.com.

- Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up here.

- And sign up for Axios What's Next newsletter, launching 6/14 and covering the latest megatrends in work, transportation, cities and more.

| | | | | | 1 big thing: The long drive toward ending HIV/AIDS once and for all |  | | | Illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios | | | | After watching the swift success story of COVID-19 vaccines, researchers and advocates are hopeful renewed funding and vaccine advances might finally lead to an end to the devastating 40-year-old AIDS epidemic, Axios' Eileen Drage O'Reilly writes. The big picture: HIV is more difficult to target than the coronavirus responsible for COVID-19 because the virus can mutate quickly and a vaccine would need to trigger a broadly neutralizing antibody response. - The other "showstopper" about HIV is that unlike other types of viruses that infect and kill cells, HIV is a retrovirus that integrates its genome into the genome of cells very quickly and very early after infection, NIAID director Anthony Fauci tells Axios.

The state of play: Death rates from AIDS have dropped dramatically, particularly in the U.S., where new annual HIV infections decreased 73% from 1981 to 2019, the CDC reported Thursday. However, disparities persist and worries have grown about the COVID-19 pandemic's impact on the AIDS epidemic. - Examining the disparities in HIV incidence in 2019, the CDC said Thursday that 70% of new infections were in gay and bisexual men. African Americans accounted for 41% and Hispanic/Latinos 29% of new cases. And a recent CDC survey of seven cities found 4 out of 10 transgender women had HIV.

- A lot of the disparities come from distrust in the health care system, racism, language barriers, stigma, plus a lack of education, awareness and access, says Carl Schmid, executive director of the HIV+Hepatitis Policy Institute.

- "The stigma associated with HIV is the one thing that has remained constant of the past 40 years," Schmid says.

"The biggest challenge is that there are still tens of thousands of cases that occur in the United States every year, that we don't have a true cure or a vaccine, and that because HIV is not in the headlines, there's often complacency that it's not a major problem anymore," Amesh Adalja, senior scholar at Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, tells Axios. - The biggest accomplishment over the past 40 years has been developing PrEP and treatments like antiretroviral therapy that can block certain stages of viral replication, Adalja says. "That's allowed HIV to no longer be a death sentence."

But a vaccine could offer the key to halting the epidemic. - To succeed with an HIV vaccine, Fauci says researchers need to find a better HIV immunogen, or antigen, to target for an immune response, like the spike protein that many of the COVID-19 vaccines focus on.

- The NIAID's clinical trial of an investigational HIV vaccine called HVTN 702 failed, although other trials continue.

- Fauci, Adalja and others hope the mRNA vaccine platform that has offered an adaptable and flexible tool to fight COVID-19 may be able to help combat AIDS as well.

- But "it's unclear yet whether that's going to work" with HIV, Adalja says.

What's next: Now that the urgency of COVID-19 is diminished a bit in the U.S. and the new vaccine platform has been proven, advocates hope more attention and funding will be given to this 40-year epidemic. - The funding proposed by the Biden administration falls a little short of what was requested, Schmid says, but it would continue a positive momentum if Congress passes it.

- "We know how to prevent HIV, we know how to treat HIV, and we know we can end it. But we need the leadership and the resources to make sure it happens," Schmid says.

Go deeper: Fauci interview: Reaching for a "home run" in AIDS research |     | | | | | | 2. Pandemic prepping |  | | | Illustration: Eniola Odetunde/Axios | | | | Scientists and public health experts are trying to leverage lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic to spur the development of technologies and infrastructure needed to stop the next big outbreak. Why it matters: Scientists predict infectious disease outbreaks will become more frequent, and the COVID-19 pandemic showed the enormous costs of not being adequately prepared. Driving the news: Eric Lander, the newly confirmed White House science adviser, told AP's Seth Borenstein that, when the next pandemic-potential virus emerges, he wants to be able to have a vaccine available in about 100 days. - The main route to achieving that timeline depends on the further development of "plug-and-play" vaccine platforms, like the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines made by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna, and determining if they can be tested — and brought to market — more rapidly.

- There are also efforts underway to create universal vaccines that protect against a range of flu viruses or coronaviruses, Axios' Caitlin Owens writes. But they face a number of technical and financial hurdles.

Beyond vaccines, there are calls to build out early warning systems for pandemics. - The technology exists to spot emerging pathogens, but there is a need to coordinate it globally, according to recommendations released today by the Milken Institute.

- The authors say there's a need for a nongovernmental coordinating center that sits aside governments and works with existing institutions, including the WHO, and that better leverages the capabilities of the private sector. They envision building capacity at the local level for labs to sample and sequence pathogens and then feed that information into an appropriate response network.

- "We don't have a robust local presence or communication vehicle right now," says Esther Krofah, executive director of FasterCures at the Milken Institute.

Yes, but: Geopolitics can get in the way of the global buy-in and coordination needed for pandemic surveillance. - Our thought bubble: "Technologies like mRNA vaccines that can cover for inevitable and impossible-to-fix political weaknesses will be particularly valuable going forward," Axios' Bryan Walsh notes.

The bottom line: "The COVID-19 pandemic showed the fault lines of what we thought we were prepared for," says Carly Gasca of the Milken Institute. |     | | | | | | 3. Catch up on COVID-19 |  Data: The COVID Tracking Project, CSSE Johns Hopkins University, state health departments; Map: Andrew Witherspoon, Michelle McGhee/Axios "The U.S. has brought new coronavirus infections down to the lowest level since March 2020, when the pandemic began," Axios' Sam Baker and Andrew Witherspoon write. 25 million COVID-19 vaccine doses will be shared globally by the U.S., with 75% going to the COVAX initiative and focused first on Latin America, Southeast Asia and Africa, Axios' Orion Rummler reports. It's the first wave of 80 million doses that Biden has pledged to share this month. The global pool of flu viruses may have shrunk due to mask wearing, social distancing and other COVID-19 pandemic control measures, STAT's Helen Branswell reports. That could potentially simplify the selection of viruses included in the annual flu vaccine. The NIH launched a clinical trial to study the safety and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccine combinations, per Axios' Rebecca Falconer. A new naming system that uses Greek letters for coronavirus variants is being adopted by the WHO, Nature News' Ewen Callaway writes. |     | | | | | | A message from University of Nebraska Medical Center | | UNMC and Nebraska Medicine to lead pandemic response program | | |  | | | | The University of Nebraska Medical Center/Nebraska Medicine brought world-class research and response expertise to fight the COVID-19 pandemic. Now we are working to better respond to future pandemics. Read more about the Project NExT initiative and how we are working to keep America safe. | | | | | | 4. A genetic recode | | Bacteria with a completely synthetic genome can be engineered to create new proteins from building blocks not naturally found in cells, researchers report today in Science. Why it matters: The approach could ultimately be used to turn cells into programmable factories for new therapeutics and polymers, says Jason Chin of the Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology in the U.K. and one of the study's authors. How it works: Life is built upon a set of 20 amino acids that are strung together in cells to create proteins. - 64 combinations or codons of the nucleic acids in DNA encode those 20 amino acids. Some of them are produced by more than one codon and some by up to six.

- In previous work, Chin and his colleagues reduced the number of codons in E. coli cells while keeping the ones that encoded molecules called transfer RNAs. Those molecules read codons and add the correct amino acids to the right position in a protein as it is built.

What's new: The researchers have now removed the genetic code for the transfer RNAs that recognize the codons they had deleted from the cell. - Viruses reproduce by using a cell's machinery. When the researchers tried to infect their synthetic bacterial cell with viruses, they found the viruses couldn't replicate, evidence that the bacteria didn't have the transfer RNAs the viruses needed. (Bacteria that still had the molecules were infected.)

- The team also demonstrated they could reassign codons to two amino acids not found in nature and put them together to form a fragment of a polymer.

What's next: Chin says they want to explore the range of polymers and bonds they can form and, ultimately, "we want to be able to encode and discover materials that have new properties but also want to have a route to degradation and recyclability of those molecules." The intrigue: The approach the researchers took is analogous to a hypothesis that the genetic code itself may have evolved as codons went through a state where they didn't have meaning to a cell and then get reassigned, Chin says. - The team showed this can be done synthetically, he says. "It is not proof but experimental variation that it is plausible."

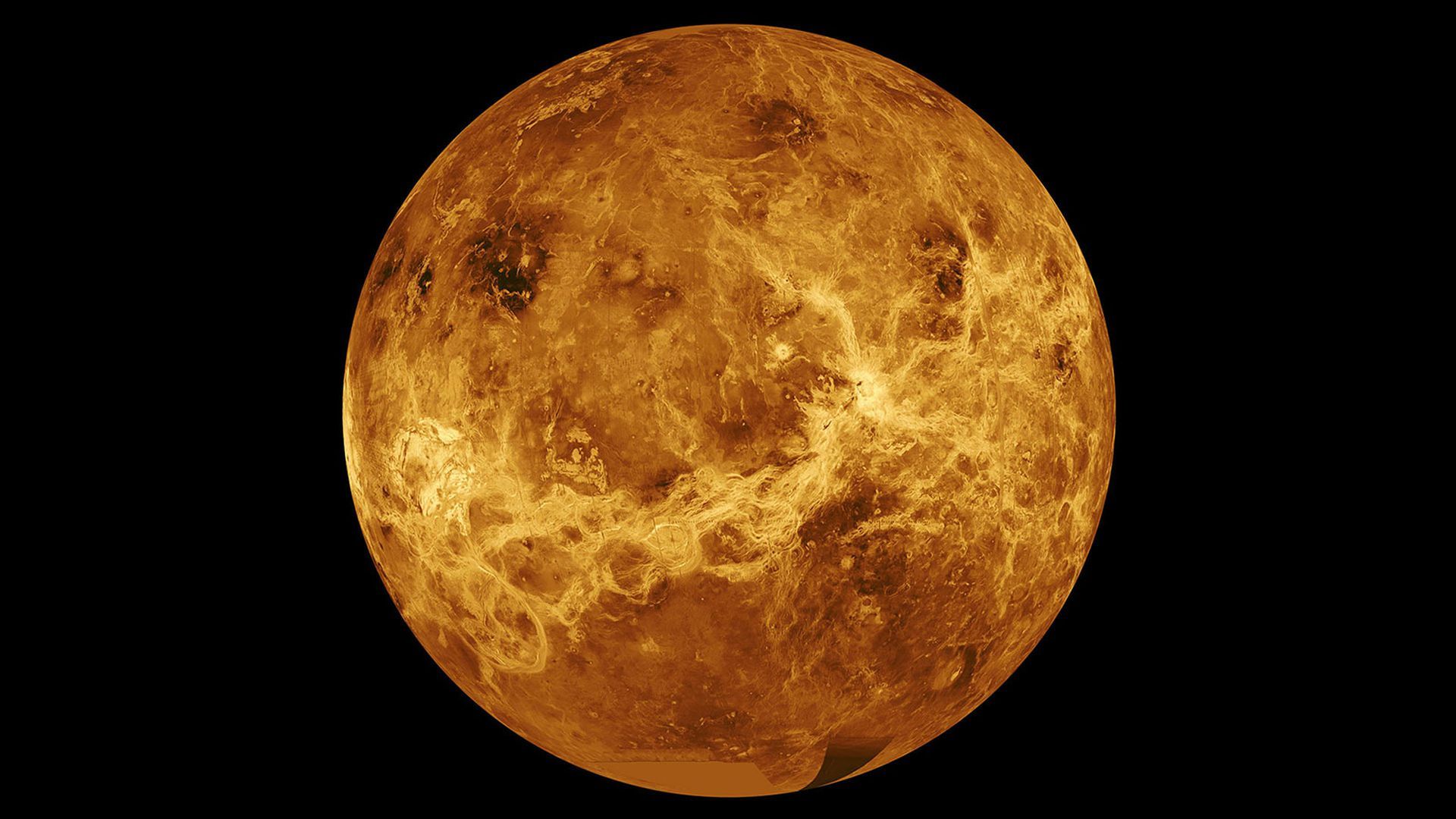

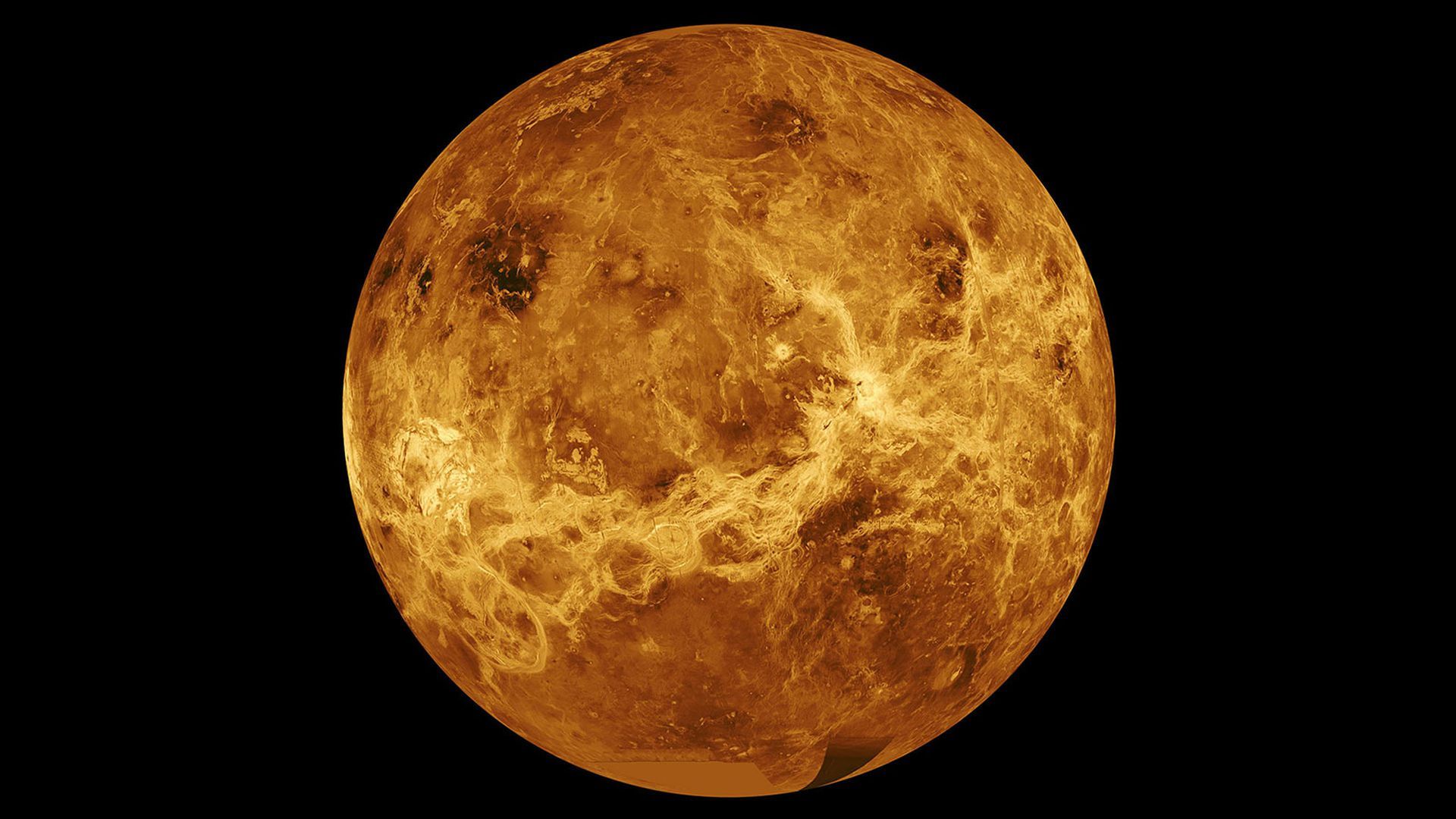

|     | | | | | | 5. Worthy of your time |  | | | Venus in full view. Photo: NASA/JPL-Caltech | | | | NASA is going back to Venus (Miriam Kramer — Axios) Labs: The $10 billion bright spot in the battered world of office real estate (John Gittelsohn — Bloomberg) Bringing bison back to the Great Plains (Louise Johns — Undark) |     | | | | | | 6. Something wondrous |  | | | An 8-week-old yellow retriever puppy follows a human point to find hidden food. Photo: Canine Companions for Independence | | | | By our side for thousands of years, dogs are masters of understanding human communication. A new study finds their ability to understand social cues emerges from an early age — without much training — and that genetics plays a key role. Why it matters: The findings suggest human preferences for communication may have shaped the domestication and evolution of one of our best animal friends. It could also help researchers to understand dogs' social cognition — and how it compares to humans. - The dogs' abilities to evaluate social cues were similar to humans — and appear to be more sophisticated than chimpanzees and bonobos, our close social relatives.

What they did: 375 8-week-old golden and Labrador retriever puppies or a mix of the two breeds, which were bred to be service dogs and had spent most of their lives at that point with their littermates, were given a range of cognitive and behavioral tests to assess their responses to human gestures, speech and interaction. - Some of the puppies used pointing and gazing from humans to successfully complete the task of finding a treat hidden under a cup, starting with their first trial, researchers led by Emily Bray of the University of Arizona, Tuscon, and Canine Companions for Independence report today in the journal Current Biology. Their performance didn't improve over 12 trials, indicating they weren't learning over time.

- Speech was important, too: Experimenters had to initiate the interaction with the dog using a high-pitched voice.

Knowing the pedigree of the puppies, the researchers then tried to tease out whether genetics played a role in the differences in the individual puppies' abilities. - They found more than "40% of the variation in dogs' point-following abilities and attention to human faces was attributable to genetic factors." (Other abilities — including the tendency to approach the experimenter or to use a marker placed next to a cup to indicate the food — were less heritable.)

What's not known ... the cognitive mechanisms dogs use to follow these cues and the specific genes that are implicated in playing a role in these social behaviors, says Bray. What they're saying: Scientists have long debated whether the ability of dogs to follow human social cues was innate or learned. - The new study suggests dogs have innate skills and that the ability to follow social cues was actively selected by humans in early dog domestication, says Zachary Silver, a graduate student at Yale University who studies domestic dogs and their communication and wasn't involved in the research.

The big picture: "We don't know of other species that, without extensive exposure, can successfully interpret the cues of a different species," Silver says of dogs. - "That says something interesting and important about dogs' domestication that they can communicate with their own species and others."

|     | | | | | | A message from University of Nebraska Medical Center | | UNMC and Nebraska Medicine to lead pandemic response program | | |  | | | | The University of Nebraska Medical Center/Nebraska Medicine brought world-class research and response expertise to fight the COVID-19 pandemic. Now we are working to better respond to future pandemics. Read more about the Project NExT initiative and how we are working to keep America safe. | | |  | | The tool and templates you need for more engaging team updates. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters. If you're interested in advertising, learn more here.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1300, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment