| | | | | | | | | | | Axios Future | | By Bryan Walsh ·Jan 06, 2021 | | Welcome to Axios Future, where 2021 is already making us long for 2020. Today's Smart Brevity count: 1,888 words or about 7 minutes. | | | | | | 1 big thing: "Shifting baselines" are changing what normal means |  | | | Illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios | | | | Scientists this year will update how they calculate average temperatures, altering our reference point of a "normal climate." Why it matters: What we think of as normal in life — whether in climate, politics or society — is always changing due to what's known as the "shifting baselines syndrome." Because we often miss those changes, we end up with a warped image of the present that shapes our policies and our future. What's happening: This spring the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) will update its calculation of average temperatures and precipitation. - "Normal" high and low temperatures and precipitation — the figures you might see on a daily weather report — are drawn from weather data over a 30-year period.

- Every decade forecasters shift to a newer 30-year dataset. Over the past decade that meant 1981–2010, but beginning this year averages will be calculated from 1991–2020.

Because 1991–2020 was warmer than 1981–2010 in nearly every part of the U.S., the update means what we classify as normal temperatures now will actually be higher than just a year ago, because the baseline for what's considered normal has shifted. Background: The term "shifting baselines" was coined in 1995 by fisheries scientist Daniel Pauly in what became a landmark paper. - Pauly was writing about the efforts of fisheries science to determine what was a sustainable catch level for commercial fish

- The problem, as Pauly wrote, was that "each generation of fisheries scientists accepts as a baseline the stock size and species composition that occurred at the beginning of their careers, and uses this to evaluate changes."

- By the time the next generation of scientists began their career, those stocks had declined because of overfishing. But instead of including that decline in their measurements, the new generation of scientists treats the reduced stocks as the new baseline.

Once you've awakened to the concept of shifting baselines, you begin to see it everywhere, from the effects of climate change to our gradual accommodation to COVID-19's once unthinkably high death count. - A study published last year looked at Twitter to see how people reacted to unusually hot or cold days. Researchers found the baseline for "normal" was weather that had been experienced just two to eight years before — hardly long enough to accurately perceive the changes wrought by global warming.

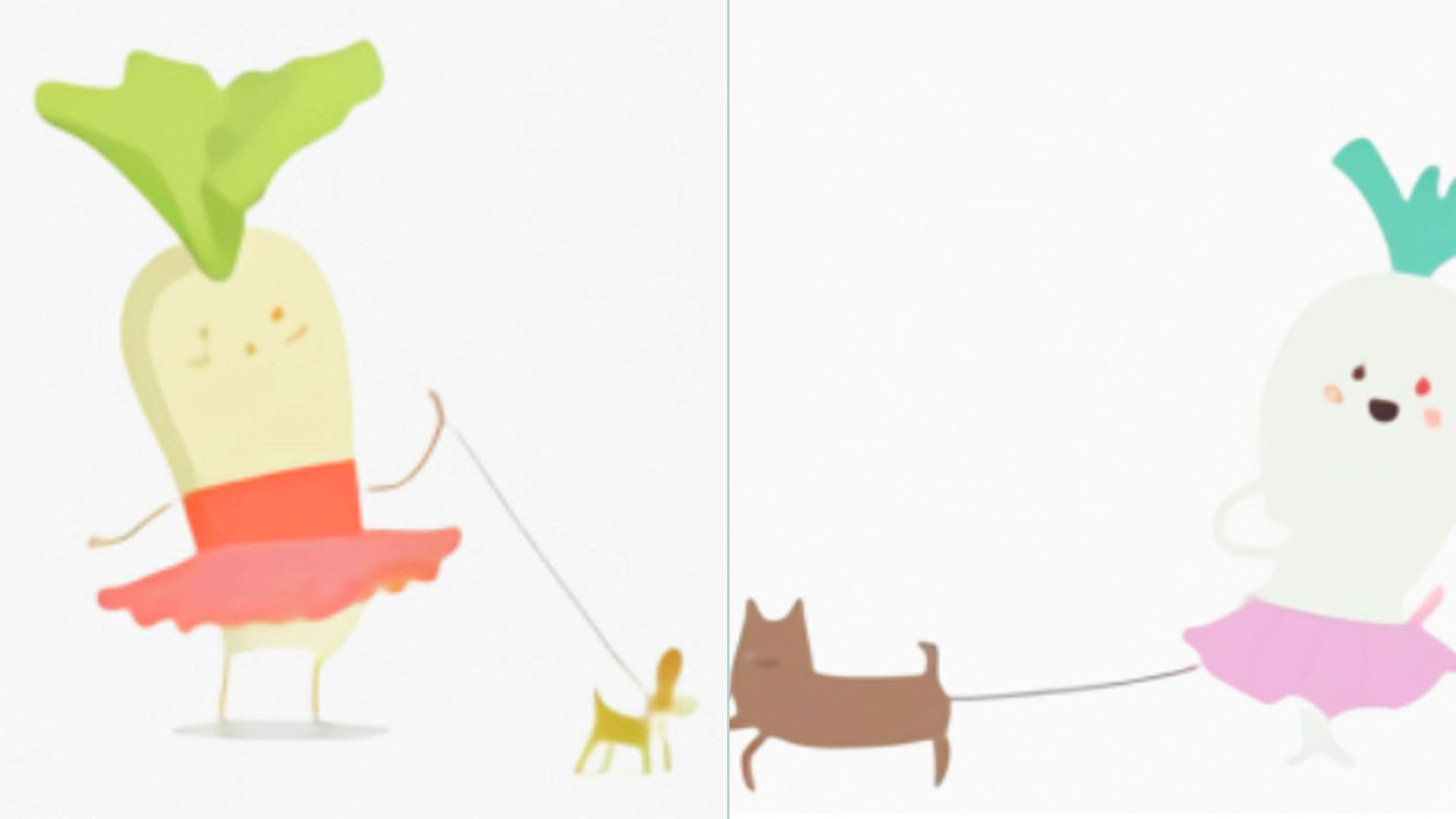

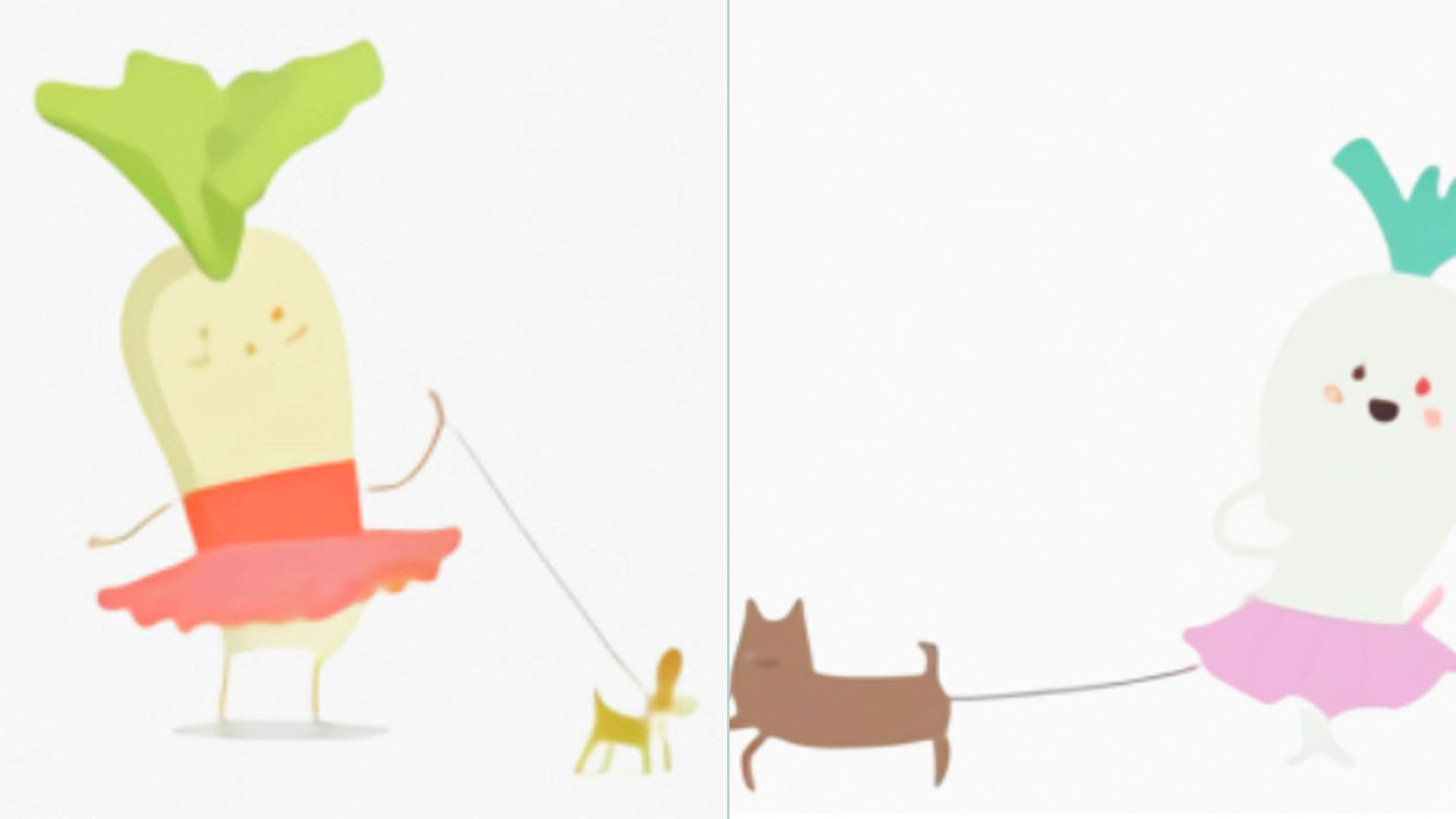

Be smart: In essence, shifting baselines syndrome results from one of the fundamental aspects of human psychology: our remarkable ability to adjust to circumstances, whether good or bad. Of note: Some climate scientists have urged weather agencies to fight shifting baselines by sticking with a static 30-year time period when calculating weather averages, rather than updating the reference period every decade. The bottom line: If we lose our way among shifting baselines, we lose our ability to value what we've accomplished in the past and fight for what we want to save in the future. |     | | | | | | 2. A new AI model generates images from text |  | | | An image generated by OpenAI's DALL-E model, from the prompt "an illustration of a baby daikon radish in a tutu walking a dog." Credit: OpenAI | | | | The machine learning company OpenAI is developing models that improve computer vision and can produce original images from a text prompt. Why it matters: The new models are the latest steps in ongoing efforts to create machine learning systems that exhibit elements of general intelligence, while performing tasks that are actually useful in the real world — without breaking the bank on computing power. What's happening: OpenAI yesterday announced two new systems that attempt to do for images what its landmark GPT-3 model did last year for text generation. - DALL-E is a neural network that can "take any text and make an image out of it," says Ilya Sutskever, OpenAI co-founder and chief scientist. That includes concepts it would never have encountered in training, like the drawing of an anthropomorphic daikon radish walking a dog shown above.

- CLIP, the other new neural network, improves on existing computer vision techniques with less training and expensive computational power.

What they're saying: "Last year, we were able to make substantial progress on text with GPT-3, but the thing is that the world isn't just built on text," says Sutskever. "This is a step towards the grander goal of building a neural network that can work in both images and text." Yes, but: Like GPT-3, the new models are far from perfect, with DALL-E, in particular, dependent on exactly how the text prompt is phrased if it's to be able to generate a coherent image. The bottom line: Artificial general intelligence may be getting closer, one doodle at a time. Share this story |     | | | | | | 3. Q&A: Ethics for the age of tech |  | | | Credit: Simon and Schuster | | | | A new book looks at how ethics can help guide decision-making at a time when corporations and technologies seem all powerful. Why it matters: Remarkable advances in AI and biotech have empowered us as a species, but have made it more difficult for individuals to navigate a changing world with their ethics intact. Susan Liautaud's new book offers a promising map for ethical behavior in the 21st century. Background: Liautaud runs a strategic advisory firm, advising corporations and nongovernmental organizations on ethics, and also teaches the subject at Stanford University. - I spoke with Liautaud about her new book "The Power of Ethics." Here are some lightly edited highlights from our conversation.

On how average people can navigate the black box nature of new tech like AI: "We don't need to understand how the AI works any more than we need to understand exactly how a car engine works. I just need to understand what matters to me. So I think what we need is to help the public assess the ethics by understanding what AI will do to us in a practical way. How is this going to impact us in the ways that really matter, like racial bias, like health, like the information silos that affect democracy." On the role government regulation should play in tech ethics: "I would tell tech companies that ethics are their greatest strategic opportunities, but left unheeded they will become their biggest risk. If tech companies really want to seize ethics as an opportunity, they would get out ahead of regulations. And similarly, regulators need to be careful that they focus on what really matters, because we don't want to quash innovation." On using powerful technologies like gene editing or geoengineering ethically: "We actually have the ability to control things, so we're talking about defining choices that could permanently change humanity. With that power comes responsibility, and one of the biggest risks today is that so many people have power that is untethered to ethical responsibility. The important question is: Who gets to decide who uses that power?" |     | | | | | | A message from Axios | | AxiosHQ: A better way to communicate with your employees | | |  | | | | What's new: AxiosHQ is a simple writing tool — perfected by Axios writers and machine learning — that helps you write with clarity and efficiency. - Why it matters: Users are seeing better alignment through more efficient internal communications.

Learn more. | | | | | | 4. The battle over the origins of COVID-19 |  | | | Vendors sell fish at an open market in Wuhan, China, last month. Photo: Getty Images | | | | A long-awaited World Health Organization-led investigation into the origins of how SARS-CoV-2 emerged is being stymied by the Chinese government. Why it matters: Understanding the origins of COVID-19 is vital if we're going to prevent the next pandemic, but the longer experts are kept out, the less chance we'll ever know the truth for sure. Driving the news: WHO director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus aired a rare public criticism of China on Tuesday for delaying authorization that would allow groups of scientists from other countries to investigate the origins of the novel coronavirus in Wuhan. Context: Even if the team is eventually allowed to begin its investigation, it will start more than a year after the first reported cases, which will make it difficult to reach any firm conclusions. How it works: Assuming it finally gets underway, the investigation will likely focus on fleshing out the prevailing theory of how the outbreak began: a bat coronavirus that somehow made its way to human beings in an example of zoonotic spillover. - But in a 12,000-word story published Monday in New York magazine, writer Nicholson Baker argued that it was possible, and even probable in his view, that what became SARS-CoV-2 "was made more infectious in one or more laboratories" through what is known as "gain of function" research, and somehow escaped into the wild.

Reality check: There is little conclusive evidence in the piece that the virus originated in a lab. The big picture: Baker is right to note the growing risk posed by gain-of-function experiments that involve creating new, more virulent or contagious strains of existing viruses in the lab in an effort to predict and prepare for future pandemics. Go deeper: The coronavirus pandemic reawakens bioweapons fears |     | | | | | | 5. Worthy of your time | | The first pig-to-human organ transplants could happen this year (Emily Mullin — OneZero) - A biotech company has plans to transplant organs from genetically modified pigs into human beings.

Inside the collapse of a disrupter: How Haven's high hopes of redefining health care came to a crashing halt (Erin Brodwin and Casey Ross — STAT) - The inside story of how three companies worth trillions of dollars were broken by the health care industry.

After the pandemic (Ted Nordhaus and Alex Trembath — Breakthrough Institute) - Two of the smartest thinkers on energy and climate provide some hope for the post-pandemic era — and a bracing dose of climate realpolitik.

Will the U.S. have another civil war? Interview with Paul Staniland (Noah Smith) - This came out over the holiday break, but it is, sadly, very timely.

|     | | | | | | 6. 1 hopeful thing: Appreciating the techno-fix |  | | | A woman receives a COVID-19 vaccine in Florida on Jan. 6. Photo: Joe Raedle/Getty Images | | | | For all the many issues with its rollout, the COVID-19 vaccine is a rare example of a true technological fix to a complex problem. Why it matters: A technology is truly valuable in the degree to which it can circumvent difficult social trade-offs. We'll need similar innovations to overcome the even greater challenges we'll face in the future. How it works: In a 1966 article, physicist Alvin Weinberg defined the "technological fix" — an innovation that can turn a complex social problem into an easier to address technological one. - Weinberg noted that social problems are more complex than engineering ones because "to solve social problems one must induce social change — one must persuade many people to behave differently than they have behaved in the past."

- Technological problems — because they don't have that same social component — are comparatively easier.

- Weinberg explored whether it would be possible in the future to circumvent those complex social problems through a technological fix.

Context: The COVID-19 vaccine, as climate scientist Roger Pielke Jr. argued in a post this week, is an example of just that kind of technological fix. - Without the vaccine, all our tools to blunt COVID-19 are social — think encouraging masks or shutting businesses — and we've witnessed how difficult it is to get an entire country to follow those social fixes for months on end.

- An effective vaccine could obviate the need for that. No trade-offs — just mRNA in a syringe.

Yes, but: Relatively few of the big challenges we face will have a technological fix as clean as the COVID-19 vaccine. The bottom line: From disinformation to climate change, we should always be on the lookout for technological fixes that can ease our burdens. - But the ultimate responsibility still lies with us.

|     | | | | | | A message from Axios | | AxiosHQ: A better way to communicate with your employees | | |  | | | | What's new: AxiosHQ is a simple writing tool — perfected by Axios writers and machine learning — that helps you write with clarity and efficiency. - Why it matters: Users are seeing better alignment through more efficient internal communications.

Learn more. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1300, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment