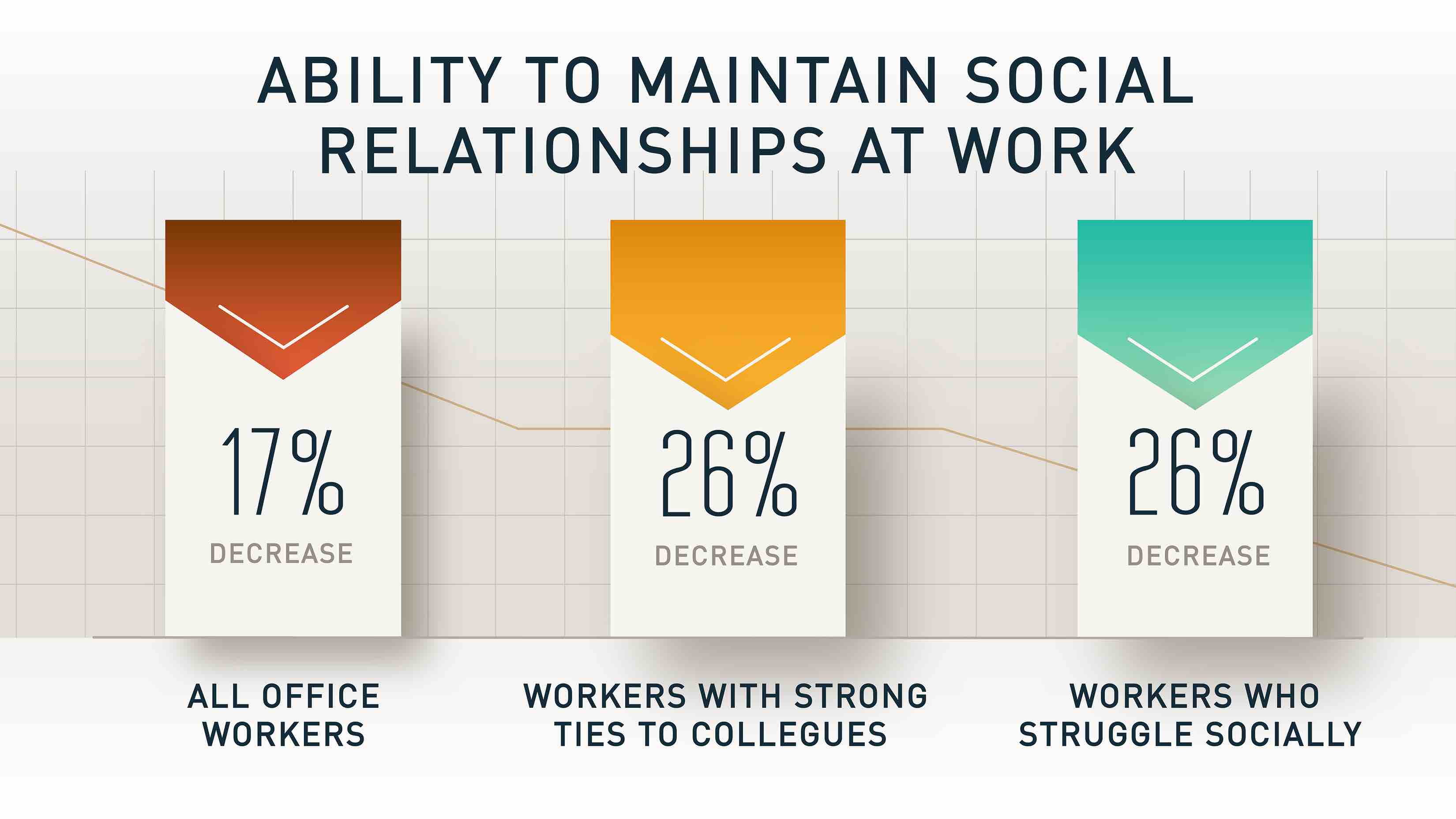

| | | | | | | Presented By WeWork | | | | Axios Future | | By Bryan Walsh ·Dec 19, 2020 | | Welcome to Axios Future, which was pleased to see President Obama likes the sci-fi show "Devs," and would love for him to actually explain it when he has a moment. Today's Smart Brevity count: 1,820 words or about 7 minutes. | | | | | | 1 big thing: Meat grown from cells moves out of the lab |  | | | Illustration: Eniola Odetunde/Axios | | | | The making of food is getting an overhaul with promising new technologies. Why it matters: What we eat and how we make it has enormous implications for the health of humanity and the planet we live on. Meat and fish grown from cells could make for a more sustainable food supply, but they still face scientific, regulatory and consumer challenges. What's happening: Earlier this week, the San Francisco-based startup Eat Just made the first-ever commercial sale of a cultured chicken product to a restaurant in Singapore, which became the first government to approve cultured meat for human consumption. The big picture: Eat Just is one of a number of startups that produces animal protein not by slaughtering animals or using plant-based ingredients that mimic the taste of meat, but by growing animal cells. - There are at least 60 cell-based meat startups around the world, according to the consultancy Lux Research, and VC funding for the sector hit $314 million in 2020 — more than 100 times greater than when Dutch pharmacologist Mark Post made the world's first cell-based hamburger in 2013.

- At least eight startups are building or operating pilot production plants to try to drive the price of production down. Cultured meat still costs $400 to $2,000 a kilogram to produce versus the current consumer price tag of $4 a pound for conventional ground beef in the U.S.

Context: The case for cultured animal protein rests on two pillars: reducing animal cruelty and taking pressure off the planet. - Approximately 70 billion chickens, 1.5 billion pigs, 550 million sheep, 460 million goats and 300 million cattle are killed every year to meet the world's growing demand for meat, while global fisheries are under extreme pressure.

- Animal meat products have by far the biggest impact on the planet and the climate per calorie, compared to other food sources.

Yes, but: There are hundreds of millions of people around the world who manage to mostly meet their nutritional needs without meat. They're called vegetarians, and many of them question the necessity of cell-based meat in a world with plenty of plants. - It's a fair point, but there's no denying that as incomes rise in the developing world, "people in general tend to gravitate toward meat whether we want them to or not," says Kate Krueger, the technical expert for XPRIZE's new Feeding the Next Billion innovation contest on alternative meat and seafood.

The catch: Producing a proper cut of cell-based meat — like a T-bone steak — requires building a 3D scaffolding for the cells, which remains tricky, and companies need to move beyond the fetal bovine serum initially used as a growth factor. - One study concluded that because of the energy consumption needed to scale up cultured meat, its carbon footprint could be several times that of conventional chicken, though that assumes companies won't use cleaner energy sources.

- Labeling will be key to future consumer acceptance — as the ongoing saga over GMO labeling shows — and some in the conventional meat industry have pushed the government to prevent cell-based companies from using the terms "meat" or "poultry."

- "It's important that consumers know what [labels] mean and that they don't confuse the product with what it's not," says Lou Cooperhouse, the CEO of BlueNalu, which is developing cell-based seafood.

The bottom line: Cell-based meat remains the most promising kind of sustainable technology, one that potentially lets us have our cake — or cultured hamburger in this case — and eat it too. |     | | | | | | 2. Human workers can keep pace with AI — if they have help |  | | | Illustration: Eniola Odetunde/Axios | | | | A new report adds more evidence to the case that AI can augment human workers, not merely replace them. Why it matters: We may still be decades or more away from the development of AI that can do everything humans can do, but as the technology continues to advance, workers will need help to get the most out of their new machine colleagues. What's happening: In a report released on Thursday, the MIT Task Force on the Work of the Future dove into the question of how AI will change our jobs. - Building on earlier research, the authors found whole-scale job loss isn't likely, and that "the most promising uses of AI will not involve computers replacing people, but rather, people and computers working together — as 'superminds.'"

The catch: Just as AI is always improving by learning, human workers need to upgrade their skills to keep pace. - To that end, the report's authors recommend programs that can enhance computer skills from kindergarten through the university level, while urging businesses and worker organizations to build cushions for the sometimes harsh changes AI will wreak on work.

Yes, but: Even as the pandemic has accelerated the diffusion of AI into the workplace — upping the stakes for human workers — millions of students around the country are suffering lifelong learning loss because of COVID-closed schools. - "I do worry about this," says Daniela Rus, director of MIT's Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory. Reducing the effects "will require effort on the part of everybody."

- Still, academic education isn't the only way to thrive in a more AI-influenced world, notes Thomas Malone, director of the MIT Center for Collective Intelligence. Social skills — one talent AI very much does not have — will be increasingly important.

"Perhaps we should worry just as much about students missing the chance to have social interactions with their friends at school as we worry about them missing their academic classes." — Thomas Malone, MIT |     | | | | | | 3. Biotech for a better mosquito repellent |  | | | The Aedes albopictus, which can spread Zika, seen way too close. Photo: Kevin Frayer/Getty Images | | | | Biotech companies are partnering with the U.S. military to engineer a better mosquito repellent. Why it matters: More than 1 million people die each year from mosquito-borne diseases, and existing repellents are limited in their effectiveness. Using synthetic biology to design a superior sustainable repellent could help change that. Driving the news: Ginkgo Bioworks announced on Thursday it had won a contract with the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to help engineer a skin-based microbiome mosquito repellent. - The contract is worth up to $15 million and includes partners from the medical dermatology company Azitra, Latham BioPharm Group and Florida International University.

How it works: DEET has been the gold standard for mosquito repellent since the 1940s, but it can cause skin irritation and degrade clothing and loses its effectiveness within hours. - Ginkgo and its partners will use high-throughput testing to discover engineered microbial compounds that can repel mosquitoes and mask the chemical volatiles released by human beings that naturally attract insects.

- "The idea is to create a repellent that you don't have to reapply," says Nádia Parachin, program director of organism engineering at Ginkgo.

Context: The contract is part of the military's ReVector program, which aims to protect U.S. military against disease-causing insects. - The project also demonstrates the way Ginkgo — which synthesizes more DNA than any other company in the world — is working to become the AWS of synthetic biology, providing its microbe-engineering expertise and production capabilities as a service.

- Just as the military can tap cloud computing services for its needs, "they can trust us to be their general purpose biology provider," says Zach Smith, director of government business at Ginkgo.

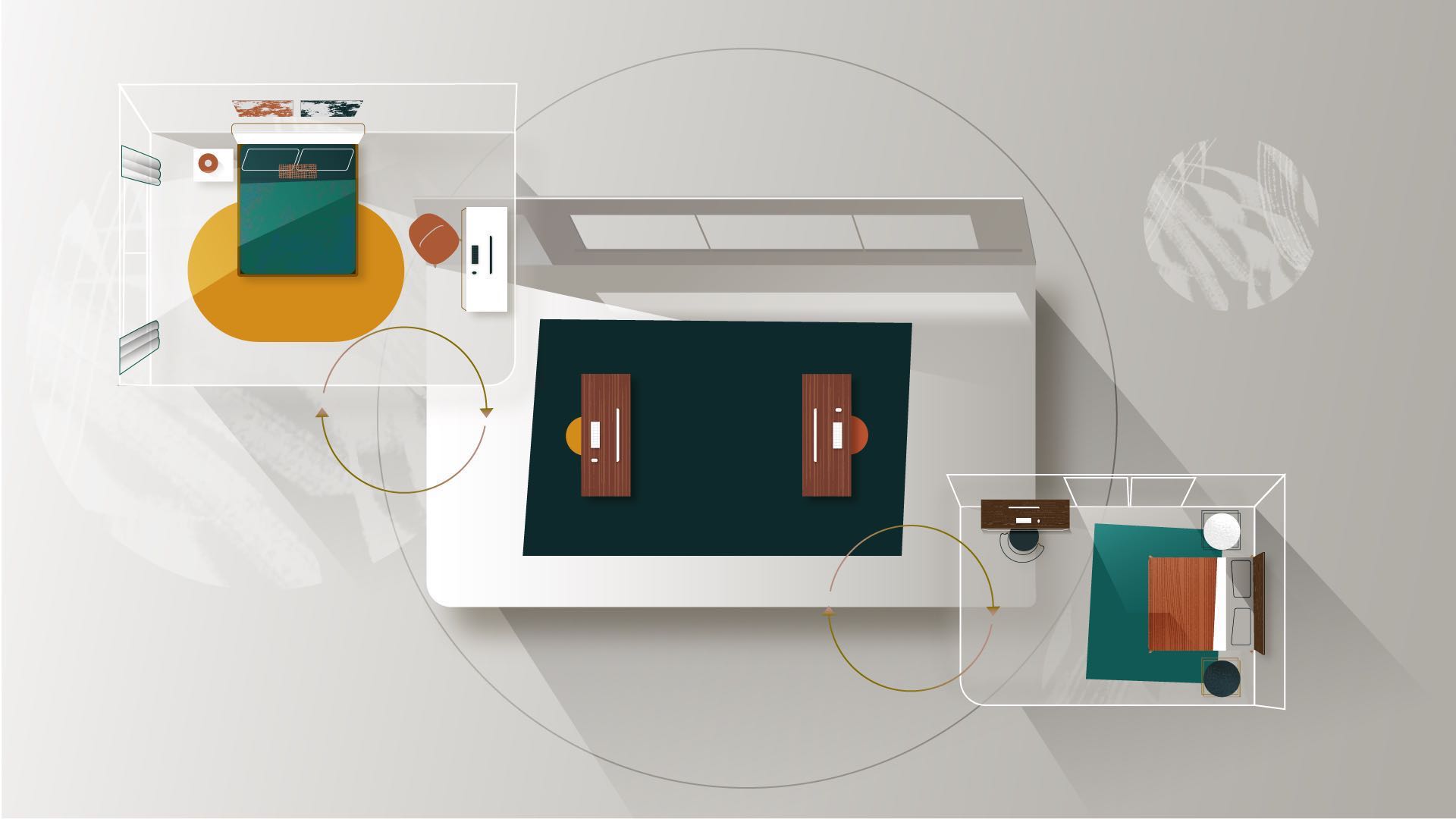

What to watch: Whether the final product is effective and safe, and whether it eventually makes its way to the hundreds of millions of people for whom a better mosquito repellent is a matter of life or death. |     | | | | | | A message from WeWork | | What to expect from the workspaces of the future | | |  | | | | Seventy-six percent of workers still see the office as a place where innovation happens, a Hamilton Place Strategies study finds. So, how can employers find solutions around distancing their workforce while offering a space that inspires people to do their best work? Peer into the future of work. | | | | | | 4. How to judge America's climate-change responsibility |  | | | Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios | | | | Historically, America has emitted the most greenhouse gases of any country in the world. But over the next 80 years, the U.S. may account for as little as 5% of such emissions, my Axios colleague Amy Harder writes. Why it matters: Installing technologies to address climate change will, therefore, be most critical in places other than America where emissions growth is expected to be higher, according to physicist Varun Sivaram. The intrigue: This concept, described by Sivaram, an expert at Columbia University, is counterintuitive given America's wealth and historical responsibility for warming the planet. Sivaram, a former top executive at a large renewable energy company in India, calls this the 5% and 95% problem. The big picture: Most debate and policy work in the U.S. focuses, not surprisingly, on how America can reduce its own emissions. President-elect Joe Biden has a 2050 goal for a U.S. economy that, on net, emits zero greenhouse gases. More and more companies and states are setting similar goals. What they're saying: That's all directly tackling, in Sivaram's words, the 5% problem — not the 95% of future cumulative emissions outside of the U.S. - "Is it important to reduce our emissions to net zero and to meet 2050 targets? Yes," Sivaram says. "But is it of equal importance to reducing the 95% problem? Probably not."

Read the entire story. |     | | | | | | 5. Worthy of your time | | Nigeria at a crossroads? (Adam Tooze — Chartbook) - The historian and author of one of the best books on the 2008 financial crisis looks at an underappreciated megatrend: the vast population growth of Nigeria.

An open letter to President-elect Biden — a tutoring Marshall Plan to heal our students (Robert Slavin — The 74 Million) - A Johns Hopkins education expert calls on the new administration to employ tutors to close the learning gap created by the pandemic.

Who gets to breathe clean air in New Delhi? (New York Times) - A brilliant interactive takes us through a day in the life of two children — one poor, one well-off — in one of the most polluted cities in the world, and shows that exposure to air pollution often comes down to wealth.

What happens when the 1% go remote? (Richard Florida — Bloomberg) - Amid news of the wealthy fleeing big cities — albeit usually for other, more copacetic cities — Florida shows how even a small shift in the wealthy can lead to a downward spiral.

|     | | | | | | 6. 1 book thing: "The Ministry for the Future" |  | | | Photo: Hachette Book Group | | | | A recent novel brilliantly illustrates the likely consequences of climate change in the decades to come, and offers hope that better technology and politics might help us save the future. Why it matters: Perhaps no subject as important as climate change has also proven so difficult to effectively and accurately dramatize. "The Ministry for the Future" is the one novel I've read that captures the consequences of warming while offering a realistic blueprint for how we can stop it. How it works: Written by the prolific author Kim Stanley Robinson, "Ministry" centers around a UN agency created in the near-future that is meant to represent the interests of generations not yet born, the generations that have the most at stake on climate change. - The inciting incident is a horrific heat wave in India, where temperatures and humidity rise so high that human beings can't survive. As a result, millions of people die in a single sweep, kicking off a desperate last-chance effort to slow warming that unfolds over hundreds of pages and a few dozen years in the novel.

- Like much of what Robinson describes, such a catastrophic event is all too possible in the years to come.

Details: Robinson is what's known as a "hard sci-fi" writer, one who engrosses himself in the minute, realistic details of everything from blockchain to geoengineering to ice sheet dynamics. - But he has a playful touch as well, narrating short chapters from the perspective of inanimate forces, like a carbon molecule or the global market.

- Beyond science, "Ministry" illustrates the knotty political and financial problems that bar the way to effective climate action — and shows how we might solve them.

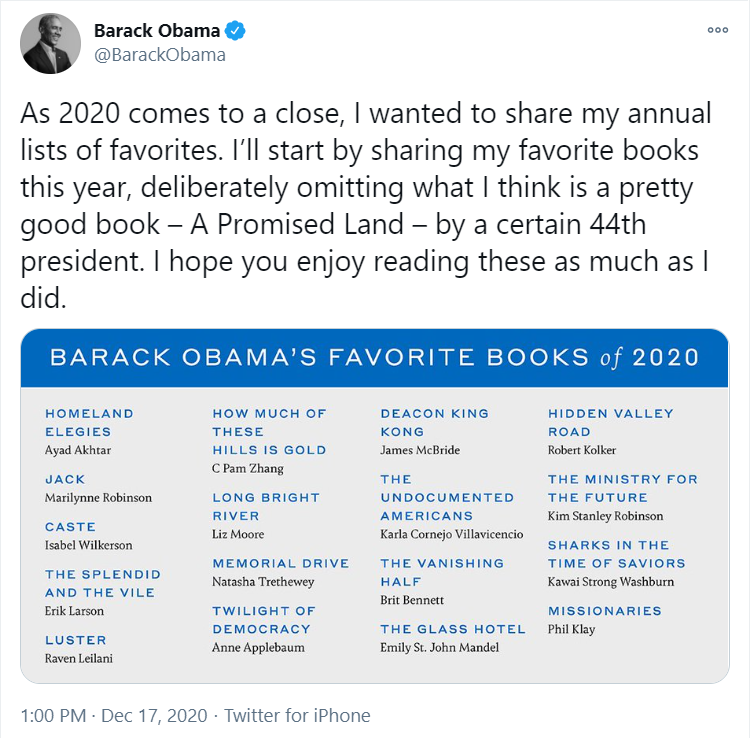

The bottom line: If you don't trust my take, just listen to President Obama. |     | | | | | | A message from WeWork | | The impact of the global work from home movement | | |  | | | | Office workers' ability to maintain social relationships has declined 17% since working from home, finds a WeWork blind study. That number is 26% for workers who struggle socially at work. See how less in-person collaboration impacts innovation. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1300, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment