| | | | | | | Presented By Wondrium | | | | Axios Science | | By Alison Snyder · Jan 26, 2023 | | Thanks for reading Axios Science. This week's newsletter is 1,437 words, about a 5.5-minute read. | | | | | | 1 big thing: What's pushing the Amazon toward the edge |  | | | A deforested and burning area of the Amazon rainforest in the region of Labrea, state of Amazonas, northern Brazil, on Sept. 2, 2022. Photo: Douglas Magno/AFP via Getty Images | | | | Two new analyses detail how land clearing and degradation are pushing the Amazon rainforest toward a tipping point of no longer being a forest that supports an abundance of life and buffers Earth from climate change. Why it matters: The findings offer insights for policy paths and priorities aimed at trying to save the climate-crucial ecosystem. Driving the news: Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and Colombian President Gustavo Petro formed a "grand pact" earlier this month to try to save the Amazon "for humanity." - The first anti-deforestation raids on Lula's watch took place last week to stop illegal clearing of the forest.

- Earlier this month, Lula signed a series of executive orders to address illegal deforestation in Brazil, which is home to 60% of the Amazon forest, and reactivated the Amazon Fund that invests in efforts to stop deforestation.

Where it stands: An estimated 13% to 17% of the original Amazon rainforest has been deforested over the last half century. - "Somewhere in the next 10% or 20%, there will be a phase shift," says James Albert, a biologist at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. A recent analysis suggests about 31% of the eastern Amazon has been deforested — far above the estimated threshold of 20% to 25%.

- "Forests exist within a range of factors that can keep them as forest," he says. But they can be pushed to a point where they turn from a forest to a savanna or degraded landscape, get too dry, and "simply burn."

What's new: In a paper published today in the journal Science, Albert and an international team of scientists report humans are causing changes to the Amazonian ecosystem in a matter of decades or centuries, as opposed to millions to tens of millions of years for natural processes. - "Organisms can't adapt in the period of decades or centuries," Albert says.

Another analysis published today looked at the lesser-known problem of land degradation in the Amazon due to logging, fires, extreme droughts and changes at the edges of the forest caused by the habitat being fragmented. - Deforestation changes the landcover and can be spotted by satellites. Degradation stems from changes in how the land is used and can be hidden by the forest canopy — a forest continues to be a forest but is degraded and weakened.

- Using data from earlier studies and new satellite images, the authors estimate about 2.5 million square kilometers of the Amazon — about 38% of the remaining forest — is considered degraded by one or more the disturbances. That's in addition to the deforestation.

- They also found the carbon lost from the forest due to degradation is on par with that due to deforestation — and degradation can lead to as much loss of the forest's biodiversity as deforestation.

Their projections suggest "degradation will continue to be a major source of emissions in the region, regardless of what happens with deforestation," says study co-author David Lapola, a research scientist at the University of Campinas (Unicamp) in Brazil. - "We need specific policies to handle degradation. It's not using the same policies and actions for deforestation," he says.

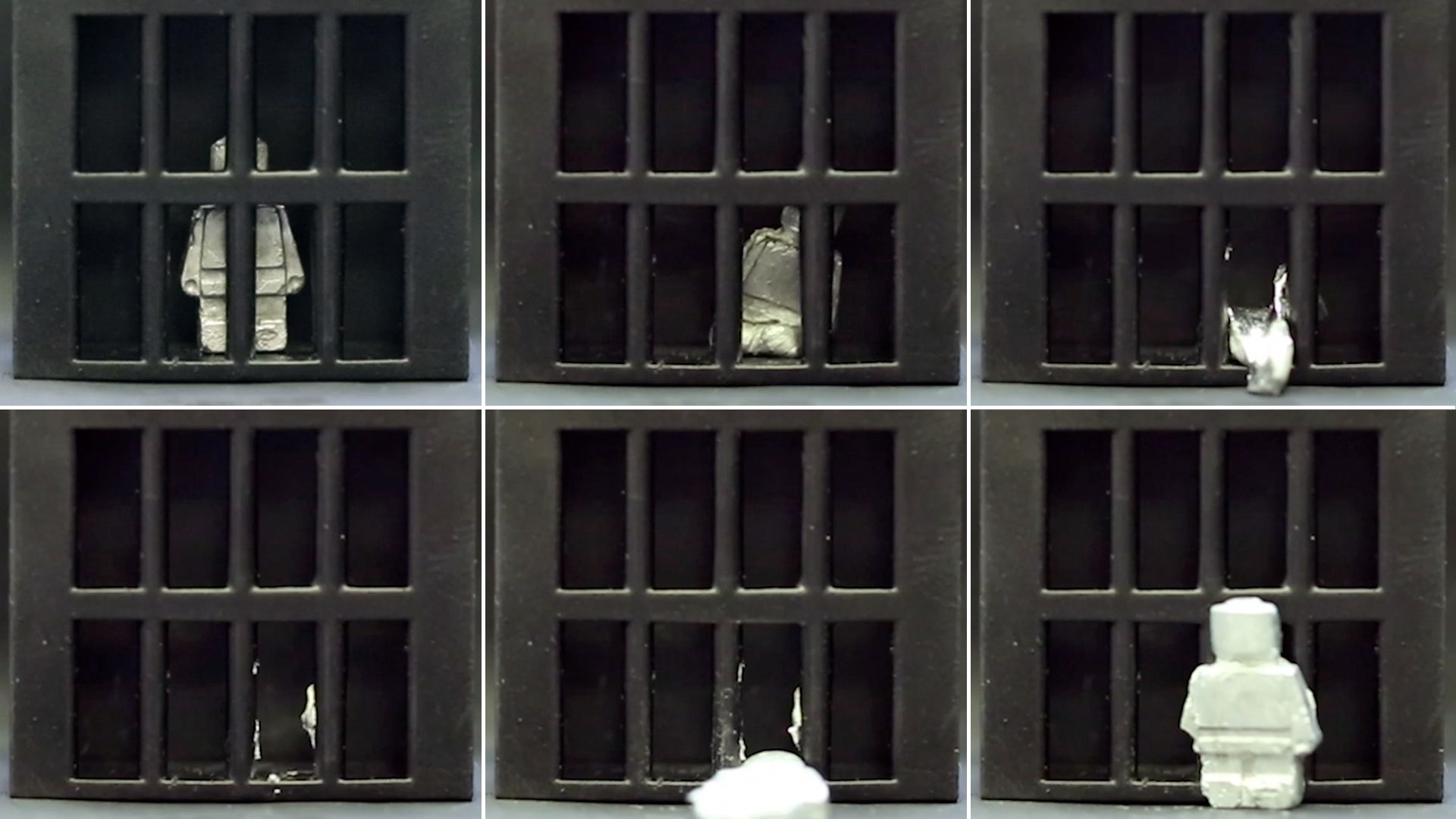

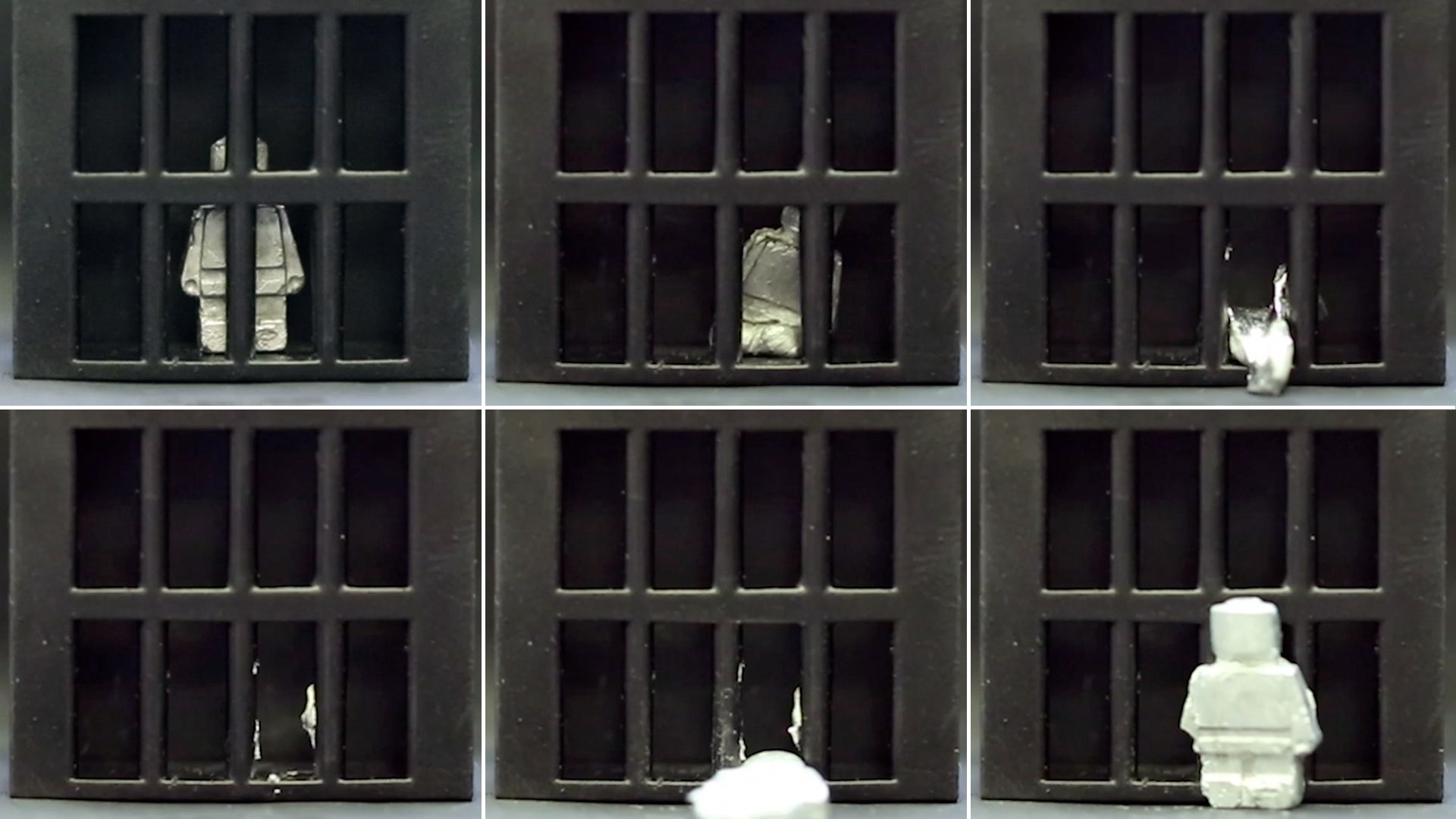

Read the entire story |     | | | | | | 2. Shape-shifter |  | | | Credit: Wang and Pan et al. Matter 6, 1–18 March 1, 2023 | | | | Scientists reported this week they've created a material that can be molded into forms that can shift between being liquid and solid. Why it matters: Shape-shifting materials could be used for a range of applications — from biomedical devices to electrical circuitry that could be wirelessly repaired, study co-author Carmel Majidi, a professor of mechanical engineering at Carnegie Mellon University, told me in an email. How it works: The material is made from the metal gallium — which melts at about 86 degrees Fahrenheit — embedded with magnetic particles. - Electricity generated from a rapidly alternating magnetic field creates heat that liquifies the metal.

- A magnet is then used to move the material around. When it cools back down to room temperature, the metal solidifies.

- The researchers' inspiration? Sea cucumbers that can soften into a material that sinks between your fingers — and then stiffen again.

In one experiment, the material was cast as a Lego-like figure, liquified and moved out of a jail cell, then recast in a mold. - They also tested the material by having it jump over moats and climb walls.

- In another experiment, it softened around a small ball in order to remove it from a model stomach — a proof of concept for potential biomedical applications.

Yes, but: Operating in the human body would likely require a non-toxic material that could degrade and one with a higher melting point, which could possibly be created by adding other metals to gallium, the authors note. |     | | | | | | 3. Light pollution's existential threat to astronomy |  | | | Illustration: Natalie Peeples/Axios | | | | The night sky is getting dramatically brighter due to light pollution spreading across the globe — and it poses an existential crisis for our ability to study space, Axios' Miriam Kramer writes. Why it matters: Information about distant galaxies and star systems gathered through telescopes and other tools is vital for humanity's understanding of our place in the universe. Driving the news: A new study published in Science last week found through 51,351 citizen scientists' observations from 2011 to 2022 that light pollution increased the brightness of the night sky by 7% to 10% per year. - That increase is far more than estimates made through satellite measurements that previously suggested an increase of about 2% per year.

- Another study published at the end of 2022 found 21 of 28 "major astronomical observatory sites" are under skies that have a level of light pollution that is able to seriously affect their observations.

The intrigue: Scientists have found light pollution affects animal migration patterns and sleep-wake cycles, and it harms insect populations that birds and other animals depend on for food. - "We are cutting territory with walls of light," Fabio Falchi, a light pollution researcher who was uninvolved in the new study, tells Axios.

- "A bridge over a river is not a wall for some species, but during the night when it is lighted, this light is cutting the river in half for some species. So we are fragmenting the environment where animals live."

- According to Christopher Kyba, a researcher with the GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences and one of the authors of the new study, a good rule of thumb is to only light what needs to be lit — like a sign — when it needs to be lit and only the amount of light that you need for it to be seen.

Between the lines: The increase in light pollution each year is likely, in part, caused by growing cities and wasteful lighting techniques, Kyba said. - "When you see that the sky keeps getting brighter, year after year, it means we're just doing a bad job of lighting our cities," Kyba said, adding that taxpayers are paying for much of that lighting. "We're also using a lot of fossil fuels to produce all of that light."

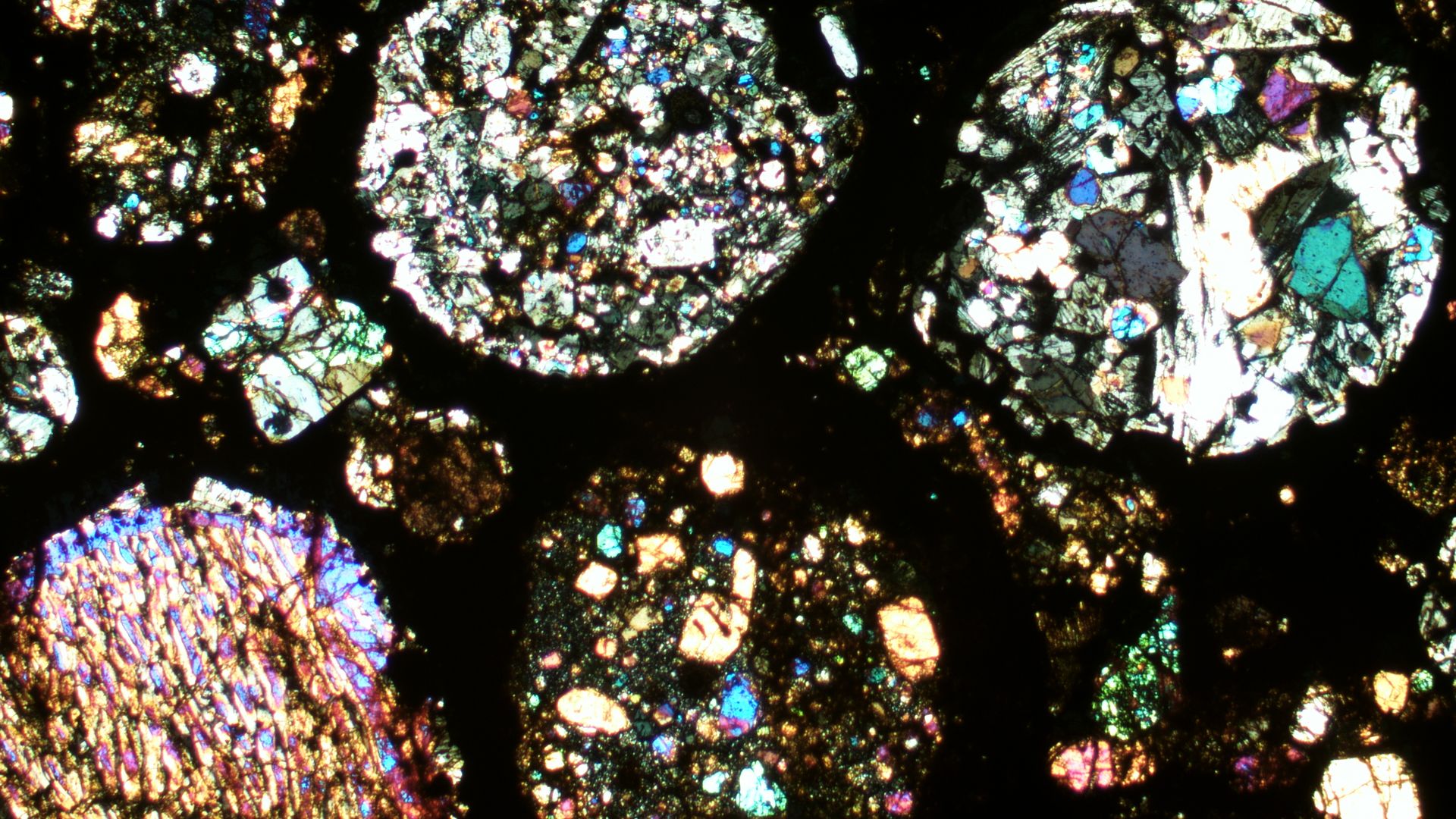

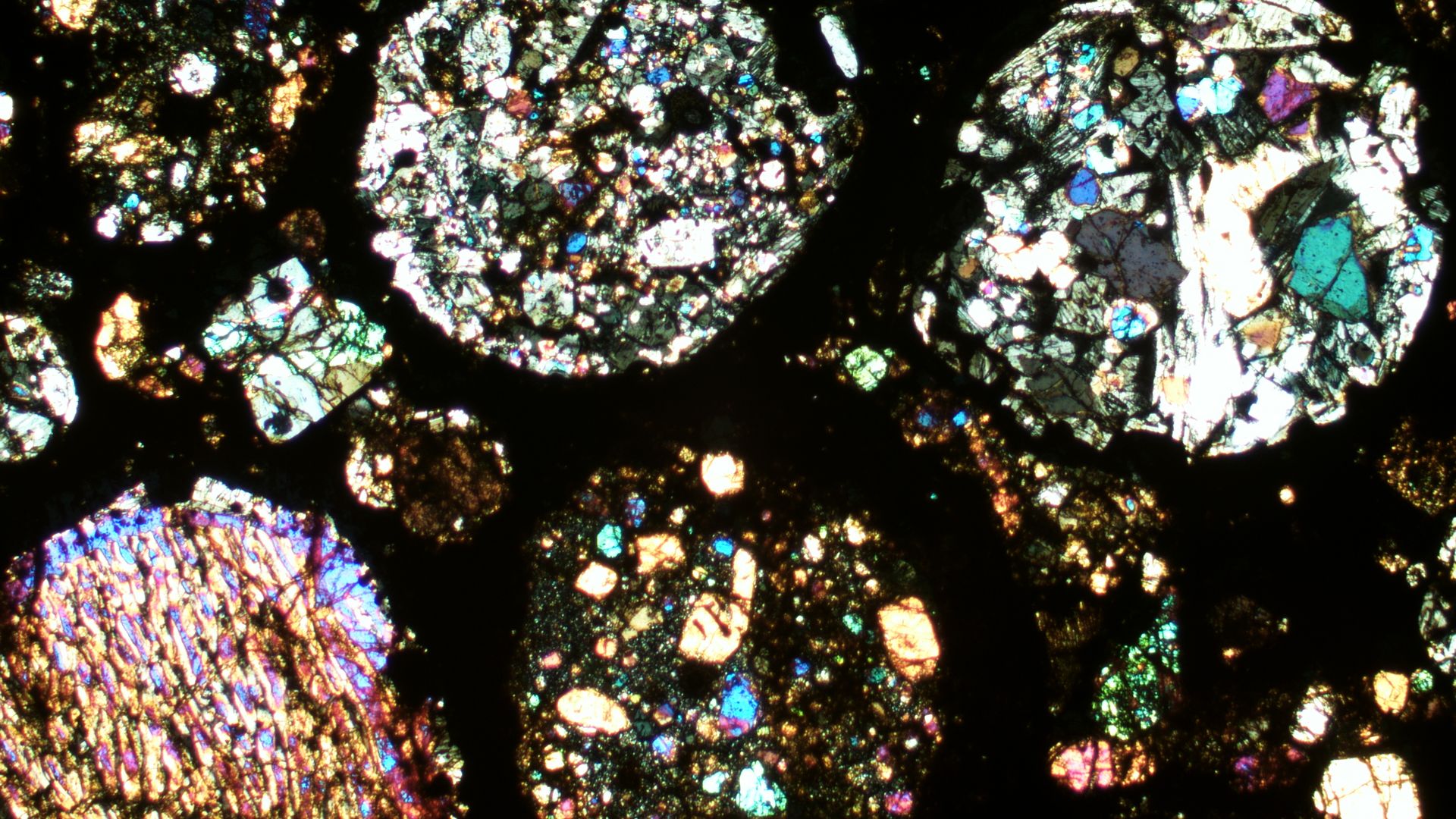

Read the entire story. |     | | | | | | A message from Wondrium | | Explore the world — anytime, anywhere | | |  | | | | Learn anything about everything with expert-led courses, documentaries and other immersive educational adventures. Here's how: From history to cooking to business, discover more about the world from your favorite device. Start with a 14-day free trial — then save 50% off your first 3 months. | | | | | | 4. Worthy of your time | | Humans and wild apes share a common language (Victoria Gill — BBC) Weird supernova remnant blows scientists' minds (Shannon Hall — Nature) Ukraine's scientists receive a funding lifeline from abroad (William Broad — NYT) |     | | | | | | 5. Something wondrous |  | | | A thin section of primitive meteorite under a microscope. Credit: Nicole Xike Nie | | | | Some of the volatile elements involved in forming Earth existed closer to the Sun than scientists thought, according to two new studies. The big picture: Meteorites carry a record of the materials that built Earth — and potentially clues about how planets might form around other stars. - Meteorites that came from the far edge of the disk of gas and dust from which the solar system formed have different ratios of isotopes of elements than those that formed closer to the Sun.

- And, meteorites formed close to the Sun — called noncarbonaceous chondrites — have a ratio of isotopes of some metals similar to that found in metals on Earth, indicating these Earth ingredients came from the same part of the solar system.

- But volatile elements, like potassium and zinc, haven't been detected in these same types of meteorites.

What's new: Two papers published in Science today report measuring ratios of potassium and zinc in noncarbonaceous chondrites and detecting anomalous patterns in them that are similar to those found in rocks on Earth. - The findings indicate at least half of the zinc and 80% of the potassium on Earth came from the inner regions, in line with previous research.

- Together, the studies suggest about 90% of Earth's mass came from materials from the inner solar system.

"This is a game changer for cosmochemistry," Nicole Nie, an author of the paper studying potassium isotopes and planetary scientist at the California Institute of Technology, told Science's Paul Voosen. |     | | | | | | A message from Wondrium | | Start binge-learning in 2023 | | |  | | | | Go from binge-watching to binge-learning. With Wondrium, find new passions or dig deeper into your favorite topics with expert-led courses, documentaries and other educational adventures. Start with a 14-day free trial — then save 50% off your first 3 months. | | |  | | Are you a fan of this email format? Your essential communications — to staff, clients and other stakeholders — can have the same style. Axios HQ, a powerful platform, will help you do it. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

To stop receiving this newsletter, unsubscribe or manage your email preferences. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment