| | | | | | | | | | | Axios Science | | By Alison Snyder ·Mar 24, 2022 | | Thanks for reading Axios Science. This week's newsletter is 1,657 words, about a 6-minute read. - Send your feedback and ideas to me at alison@axios.com.

- Sign up here to receive this newsletter.

- 🎉 ¡Feliz cumpleaños! Happy first birthday to Axios Latino. Sign up here for the twice-weekly newsletter.

| | | | | | 1 big thing: The great debate about animal emotions |  | | | Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios | | | | A longstanding debate about whether animals have emotions and feelings is being reshaped by new tools and concepts. Why it matters: Understanding whether non-human animals have emotions — and how they are formed if they do — could provide new insights into the mental health of humans. The big picture: Emotion is tricky to study. There isn't a formal, widely held definition of what an emotion is, and neuroscientists, biologists, psychologists, anthropologists, sociologists and philosophers all have different views. - One question among them centers on how much emotions are hardwired in networks of neurons in the brain that may even be found across humans, mammals and other animals, or if they are the products of a conscious brain influenced by culture, experience and learning.

Many studies of human emotion have leaned on asking people across cultures to match facial expressions to emotions. That they often assigned the same emotion to the same expression led some psychologists to conclude there are a handful of universal basic emotions like fear or anger that are innate. - But the method is criticized by some researchers and the idea of basic emotions is contested. "Nobody can tell you what the rules are for getting non-basic emotions out of basic emotions," says Andrew Ortony, a professor emeritus of psychology at Northwestern University who leans to the side of culture guiding emotion.

- Primatologist Frans de Waal of Emory University, who studies behavior in chimpanzees and other animals, also says to continue focusing on the face as the window to emotional experience is "misguided" but for different reasons. It omits animals without facial expressions, like dolphins or fish, and it implies love, hope and other emotions not in the basic bucket are uniquely human, he says.

"I think all emotions that humans have are variations on animal emotions," he says. What's new: Increasing evidence suggests crabs and some other invertebrates — in addition to fish and mammals — experience emotions, de Waal and philosopher Kristin Andrews of York University in Toronto write in Science today. - Crabs have been found to stay away from parts of a tank where scientists have shocked them. De Waal and others argue such learned behavior isn't an unconscious reflex because the crabs are actively avoiding those spots, meaning they must be centrally processing that going there does not feel good.

- But by Ortony's definition, that is not the same as experiencing emotions, he says.

Studying the biology of emotion in mice, fruit flies, jellyfish and other animals is also important because it allows scientists to perform biological experiments they can't do in humans, Caltech neuroscientist David Anderson writes in his new book, "The Nature of the Beast." - They can use tools like optogenetics to switch neurons on and off in the brains of rodents and other animals to see whether they cause an emotion or if their activity is a consequence of an emotion.

- That information "matters if you are trying to decide which type of neuron to study in order to search for a new treatment for anxiety disorders," he writes.

|     | | | | | | Part II. The case that animals have emotions | | Unlike humans, other animals can't tell scientists if or how they feel. (Humans aren't exactly reliable here either: We lie about our feelings, aren't aware of them at times or just can't describe them. Ask any therapist.) - But Anderson argues that doesn't matter. For him and others, emotions are internal, unconscious states of the brain's neurons that exist separate from a feeling, which is conscious.

- These emotional states can be seen in behaviors like aggression, which have different properties — they persist and their intensity can vary — that distinguish them from reflexes, Anderson writes.

- Those "emotion primitives" are seen in the behavior of mice and fruit flies, and in the neurons in their brains that are associated with those behaviors, he writes. That suggests they are common and innate — but he says that doesn't mean flies' emotions are as complex as those of mice or humans.

But, but, but ... New York University neuroscientist Joseph LeDoux, whose research focuses on fear, argues these ancient circuits of neurons seen in different species may very well control defensive behavior but that fear is a conscious feeling assembled through cognition, which evolved more recently. Most scientists acknowledge part of the confusion and cross-talk about emotion in science is rooted in the loose language of our everyday experience as humans that can affect how even they talk about emotions and feelings, with the terms used interchangeably. - And some suspect emotions and feelings may arise from some combination of culture and biology.

What to watch: Lisa Feldman Barrett, a professor of psychology at Northeastern University who has championed the idea that emotion is culturally constructed, recently wrote that "genes and environment are so deeply entwined ... that it's fundamentally unhelpful to call them separate names like 'nature' and 'nurture.'" - In a recent study, psychologists Gaurav Suri of San Francisco State University and James Gross from Stanford University built artificial neural networks representing facial expressions, physiological responses or other features of emotion to model how an emotion occurs.

- When they gave the network inputs, they found in some circumstances the network responded in a way that is consistent with theories that say emotions are the same across people and innate, and in other circumstances with the idea that emotions are constructed or learned.

- Suri cautions it is just a model but it suggests "emotions are emergent phenomena arising from many diverse interactions. It's no use fighting about whether emotions are basic or constructed."

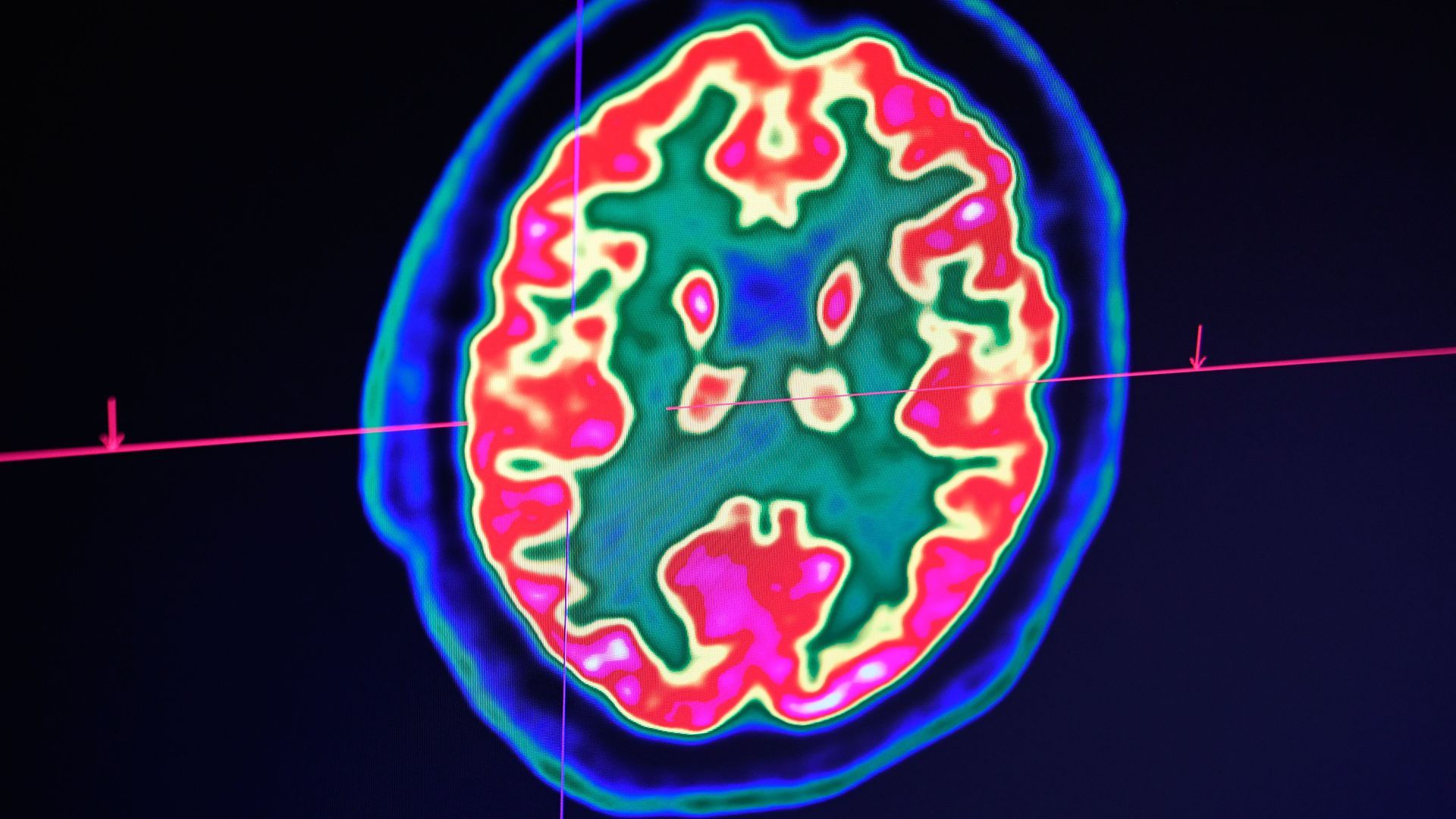

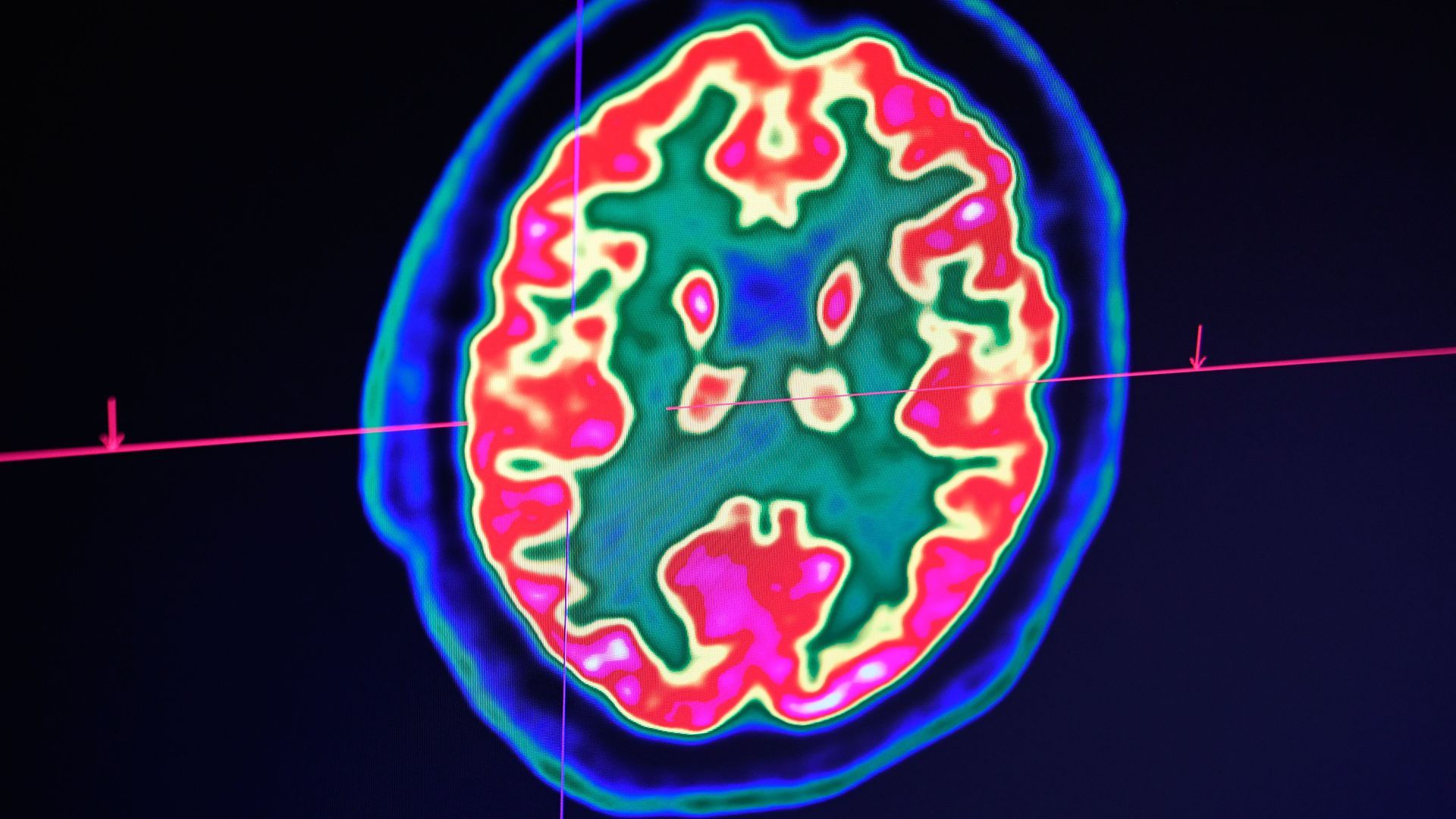

The bottom line: There is hope, whatever that is, that the nature of emotion could become clearer. |     | | | | | | 3. Catch up on COVID |  Data: N.Y. Times; Cartogram: Kavya Beheraj/Axios "The U.S. is now averaging roughly 29,000 new COVID cases per day — a 22% drop over the past two weeks," per Axios' Tina Reed and Kavya Beheraj. "The new COVID-19 variant taking root in the U.S. probably won't pose a big health threat to many Americans, thanks in part to this winter's Omicron surge," Axios' Adriel Bettelheim writes. Moderna said it will seek authorization for the use of a low dose of its COVID-19 vaccine in children ages 6 months to 6 years old. |     | | | | | | A message from Axios | | Get the top stories shaping our world in your inbox | | |  | | | | Take a tour of the most important stories around the globe with Axios World. Delivered weekly to your inbox by world editor Dave Lawler. Subscribe for free | | | | | | 4. Study: Fully paralyzed patient uses brain implant to communicate |  | | | Image of a brain. Photo: Fred Tanneau/AFP via Getty Images | | | | A fully paralyzed patient with ALS, or Lou Gehrig's disease, has regained his ability to communicate via a new brain implant, according to a study published by European researchers in Nature Communications on Tuesday, Axios' TuAnh Dam writes. Why it matters: The number of people diagnosed with ALS has risen every year and is projected to reach 300,000 by 2040, with no cure or treatment that stops or reverses the disease's progression. Details: Two microchip implants were inserted into the brain of a German patient, according to the study published by Ujwal Chaudhary and Niels Birbaumer. Afterward, the patient was able to form words and full sentences using mental impulses. - The experimental treatment was tested on only one patient in the study.

Yes, but: Chaudhary and Birbaumer had conducted similar experiments in 2017 and 2019, but both studies were retracted. - An investigation by the German Research Foundation found they had not appropriately shown details of their analyses and had made false statements, the New York Times writes.

- The foundation said that it would investigate the latest study, the Times reports.

What they're saying: Nature Communications declined to reveal how the study was vetted. - "We have rigorous policies to safeguard the integrity of the research we publish, including to ensure that research has been conducted to a high ethical standard and is reported transparently," a spokesperson told the Times.

|     | | | | | | 5. Worthy of your time |  | | | A mule deer in Grand Teton National Park in Wyoming. Photo: Karen Bleier/AFP via Getty Images | | | | How one Wyoming mule deer won friends and influenced science (Kylie Mohr — High Country News) How species adapt to survive in cities (Eric Bender — Knowable) Forests help reduce global warming in more ways than one (Nikk Ogasa — Science News) We've found 5,000 exoplanets and we're still alone (Marina Koren — The Atlantic) |     | | | | | | 6. Something wondrous |  | | | The deep-water cone snail, Conus neocostatus, catching a fish. Photo: Dylan Taylor/University of Utah | | | | The potent venom of a cone snail that lives deep in the ocean contains a pain-suppressing compound, scientists reported this week. Why it matters: The compound is similar to a hormone that inhibits pain in the human body but the snail version lasts far longer and could be used to help develop new pain medicines. The details: There are more than 1,000 species of cone snails, each with a different cocktail of toxins in their venom. - Researchers were studying one group — the Asprella clade — when they discovered the snail used a hunting strategy that hadn't been observed in the animal before.

- Instead of the taser-and-tether tactic in which a snail injects its venom and stays attached to the fish and quickly eats it, Asprella inject their venom and go back into their shell to wait. Once the fish is dead — which takes one to three hours with Asprella venom — the snail swallows it.

- That is "a very unusual predation behavior which made us think the toxins they make are unusual," says Helena Safavi-Hemami, a biologist at the University of Copenhagen and one of the authors of the study published in Science Advances.

What they found: When the researchers studied the snail's venom, they found a molecule similar to the hormone somatostatin that suppresses pain in the human body. - But unlike short-lived human and synthetic versions, the snail's compound — dubbed Conosomatin Ro1 — has a half-life of more than 158 hours, they report.

- And it binds to two of the five receptors in humans that activate pain inhibition suggesting it would work in people.

- They also studied Conosomatin Ro1's effect in mice and found higher doses of the compound decreased their sensitivity to pain.

Background: Cone snails also make a form of insulin that is being used to try to improve insulin drugs, Safavi-Hemami says. - "They've had millions of years to evolve the best compounds."

What's next: There are hundreds of toxins arranged in potentially thousands of combinations of venoms, Safavi-Hemami says. - Next, the team wants to "survey other cone snail species and find the very best cone snail toxin."

|     | | | | | | A message from Axios | | Get the top stories shaping our world in your inbox | | |  | | | | Take a tour of the most important stories around the globe with Axios World. Delivered weekly to your inbox by world editor Dave Lawler. Subscribe for free | | | | Thanks to Aïda Amer on the Axios Visuals team for this week's illustration and to Carolyn DiPaolo for copy editing this edition. |  | It's called Smart Brevity®. Over 200 orgs use it — in a tool called Axios HQ — to drive productivity with clearer workplace communications. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters. If you're interested in advertising, learn more here.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1300, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment