|

|  Hello Reader! This is the weekly email digest of the daily online journal Brain Pickings by Maria Popova. If you missed last week's edition — love, death and Whitman; George Saunders on the two keys to storytelling; Alan Turing, the world's first digital music, and the poetry of the possible — you can catch up right here. If my labor of love enriches your life in any way, please consider supporting it with a donation – for a decade and a half, I have spent tens of thousands of hours, made many personal sacrifices, and invested tremendous resources in Brain Pickings, which remains free and ad-free and alive thanks to reader patronage. If you already donate: THANK YOU. Hello Reader! This is the weekly email digest of the daily online journal Brain Pickings by Maria Popova. If you missed last week's edition — love, death and Whitman; George Saunders on the two keys to storytelling; Alan Turing, the world's first digital music, and the poetry of the possible — you can catch up right here. If my labor of love enriches your life in any way, please consider supporting it with a donation – for a decade and a half, I have spent tens of thousands of hours, made many personal sacrifices, and invested tremendous resources in Brain Pickings, which remains free and ad-free and alive thanks to reader patronage. If you already donate: THANK YOU.

|

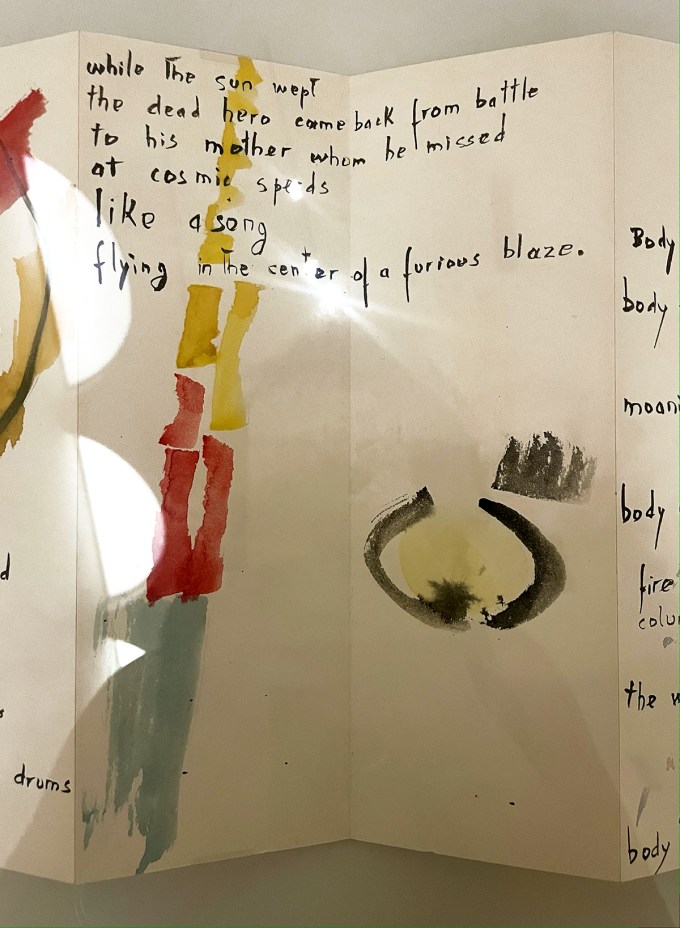

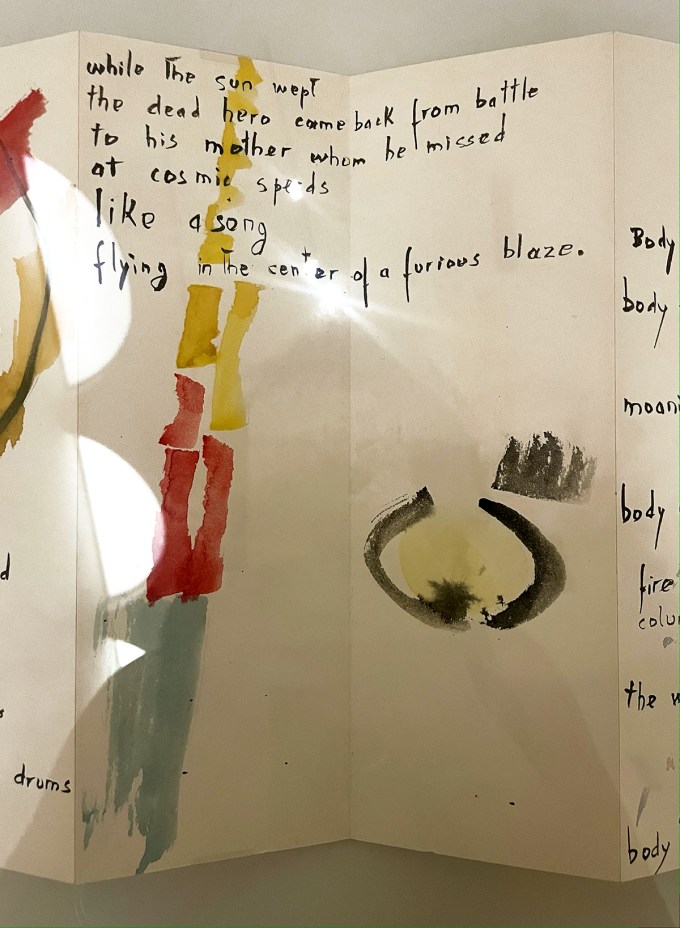

"When you realize you are mortal," the polymathic poet, painter, journalist, novelist, and philosopher Etel Adnan (b. February 24, 1925) wrote in her sixtieth year while wresting wisdom from the mountain, "you also realize the tremendousness of the future. You fall in love with a Time you will never perceive." These questions of space, time, morality, and transcendence, which continue to permeate Adnan's century-wide body of work and wonder, had come into formative focus two decades earlier, in one of her most original and unexampled works: a hybrid of poetry and painting — a new form Adnan christened leporello, after the Italian bookbinding term for concertina-folded leaflets — reflecting on a triumphal and tragic moment in the history of our species. In 1961, the Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin had become the first human animal — of all the hundred-some billion of us who ever lived and died — to leave the planet on which we had evolved several million years earlier. It was an era of terror and wonder — science had swung open new portals of possibility for knowing the miracle of life more intimately, and politics had hijacked science to build new weapons for destroying that miracle. When Gagarin perished in a plane crash seven years later under mysterious circumstances, Adnan composed an eleven-part epic poem in ink and watercolor, titled Funeral March for the First Cosmonaut — at once a memorial for the new Icarus and new scripture for the human mythos of space, painted into an accordion book, exploring the largest questions of existence: life, death, loneliness, longing, creation, destruction, the relationship between the ephemeral and the eternal, our relationship to the cosmos and to each other.  Adnan's Funeral March for the First Cosmonaut on display at the Guggenheim Museum. (Photograph: Maria Popova.)  you were searching through the hands of the monkey tree you were searching through the hands of the monkey tree

that pipeline to the sky

a light incoherent like a wave

was moving behind the clouds

and you went swimming into that distant

pool you went to be suspended there

cool as the western side of palm leaves

under the break of noon

there are potholes in the skyes

familiar to the wanderers of the sierras

moving icebergs which taste like

antimatter when physics go wild

Gagarin Scott Gherman Titov McDivitt

Komarov the new hierarchy of archangels

bringing messages from outer space

decoding the protons and moving under

a shower of travelling electrons. seven sunsets for a single evening

and the uninterrupted moon

growing into their eyes with the look

of mothers looking back on us from the other

side of our deaths Seven sunrises for a cosmonaut!

Page from Funeral March for the First Cosmonaut on display at the Guggenheim Museum. (Photograph: Maria Popova.) Born in Beirut and educated in Paris, Adnan was then living at the foot of Mount Tamalpais in California, teaching philosophy at a local university, painting and writing poetry — the polyphonous calling through which she soon met the Lebanese-American artist Simone Fattal, now her partner of half a century, who has made the most astute observation about Adnan's paintings of rising and setting celestial bodies, horizons perched on infinity, and mountains rising toward eternity: that they do for us what icons used to do for believers, conferring upon our everyday lives a certain supranatural energy, an aura of awe at the sheer miracle of existence.  Ending of Funeral March for the First Cosmonaut on display at the Guggenheim Museum. (Photograph: Maria Popova.) Funeral March for the First Cosmonaut is an elegy for humanity in the classic sense, a hybrid of celebration and lamentation — an elegy for us creatures forever "eating and remaining hungry," "kissing and remaining lonely," "speaking and remaining doomed"; creatures who bomb and imprison each other, but who also never cease to "struggle towards freedom, struggle toward meaning" with the fury of a song. In this respect, it is kindred to Maya Angelou's staggering poem "A Brave and Startling Truth," which voyaged into the cosmos aboard the Orion spacecraft a generation later.  Ulrike Haage with Etel Adan in Paris, 2019. (Photograph: Anton Maria Storch.) In 2019, having just turned 94 and living in Paris with her partner, Adnan collaborated with the German composer and sound artist Ulrike Haage on adapting Funeral March for the First Cosmonaut into an experimental radio requiem — a kind of spacetime sound installation, beautiful and haunting, fusing musical elements from the classical tradition of Gagarin's native Russia and the ancient Middle Eastern tradition of Adnan's native Beirut, embodying the opening verse of the poem's third sequence:  In the beginning was the white page In the beginning was the white page

In the beginning was the Sufi in orbit

In the beginning was the sword

In the beginning was the rocket

In the beginning was the dancer

In the beginning was color

In the beginning was music

Funeral March for the First Cosmonaut is the first artwork greeting the wonder-smitten visitor to Light's New Measure — the Guggenheim Museum's retrospective of Adnan's work, launched midway through her ninety-seventh year, titled after a line from her 2012 poetry collection Sea and Fog:  The heart is a stranger to patterns of matter or their distribution. In darkness, light's new measure. The heart is a stranger to patterns of matter or their distribution. In darkness, light's new measure.

Page from Funeral March for the First Cosmonaut on display at the Guggenheim Museum. (Photograph: Maria Popova.) Complement with Umberto Eco's semiotic children's book The Three Astronauts, written and painted in the same era, then revisit astronaut Leland Melvin reading Pablo Neruda's love letter to Earth and poet Sarah Kay performing her ode to awe, "Astronaut." donating=lovingFor 15 years, I have been spending hundreds of hours and thousands of dollars each month to keep Brain Pickings going. It has remained free and ad-free and alive thanks to patronage from readers. I have no staff, no interns, no assistant — a thoroughly one-woman labor of love that is also my life and my livelihood. If this labor makes your life more livable in any way, please consider aiding its sustenance with a donation. Your support makes all the difference.monthly donationYou can become a Sustaining Patron with a recurring monthly donation of your choosing, between a cup of tea and a Brooklyn lunch. | | one-time donationOr you can become a Spontaneous Supporter with a one-time donation in any amount. |  | |  |

|

| Partial to Bitcoin? You can beam some bit-love my way: 197usDS6AsL9wDKxtGM6xaWjmR5ejgqem7 |

|

In 1634, Rembrandt painted his wife, Saskia, as Flora — the Roman goddess of flowers and spring. One large bloom droops over her left ear from the wreath crowning her head, dwarfing the other blossoms in scale and splendor — a single tulip, its silken petals aflame with stripes of red and white. These tulips no longer exist. Today, their closest kin are known as Rembrandts. In the painter's day, these living canvases of expressionist color transfixed the human imagination across cultures, casting a singular enchantment with their sudden and mysterious eruptions of contrasting color. Lay gardeners and professional horticulturalists all over Holland, France, and the Ottoman Empire planted tulip bulbs by the hundreds, by the thousands, hoping some would bloom in this inexplicable pattern of painterly stripes. On those rare and unbidden occasions when it happened, the tulip was said to "break."  Broken tulip by Henriette Antoinette Vincent, 1820. (Available as a print, as a face mask, and as stationery cards.) Gardeners went to extraordinary lengths to force tulips to break, their techniques still insentient to the newborn scientific method, still resonant with the echoes of alchemy haunting the atmosphere of their time: They would plant beds of white tulips, then sprinkle over the soil pigment powders of the hue they wished to see stripe the white petals, hoping rainwater would wash the bulb with pigment and somehow imprint the flower-to-be. Because the history of our species is the history of humans longing for control of their fortunes and other humans exploiting this longing in the absence of knowledge and critical thought — from religions imbuing with mystical meaning yet-unexplained astronomical phenomena like comets and eclipses, to internet scammers — a new trade of charlatans emerged, promising surefire recipes (some involving pigeon droppings, others powdered plaster from the walls of old houses) to make the tulips break. But what was really at play was something no one suspected, because no one had the reference-point nodes of understanding we call knowledge. What was really at play was an epochal intersection of science and culture, the story of which Michael Pollan tells with his signature enchanting erudition in The Botany of Desire (public library). He writes:  One crucial element of the beauty of the tulip that intoxicated the Dutch, the Turks, the French, and the English has been lost to us. To them the tulip was a magic flower because it was prone to spontaneous and brilliant eruptions of color. In a planting of a hundred tulips, one of them might be so possessed, opening to reveal the white or yellow ground of its petals painted, as if by the finest brush and steadiest hand, with intricate feathers or flames of a vividly contrasting hue… If a tulip broke in a particularly striking manner — if the flames of the applied color reached clear to the petal's lip, say, and its pigment was brilliant and pure and its pattern symmetrical — the owner of that bulb had won the lottery. For the offsets of that bulb would inherit its pattern and hues and command a fantastic price. The fact that broken tulips for some unknown reason produced fewer and smaller offsets than ordinary tulips drove their prices still higher. One crucial element of the beauty of the tulip that intoxicated the Dutch, the Turks, the French, and the English has been lost to us. To them the tulip was a magic flower because it was prone to spontaneous and brilliant eruptions of color. In a planting of a hundred tulips, one of them might be so possessed, opening to reveal the white or yellow ground of its petals painted, as if by the finest brush and steadiest hand, with intricate feathers or flames of a vividly contrasting hue… If a tulip broke in a particularly striking manner — if the flames of the applied color reached clear to the petal's lip, say, and its pigment was brilliant and pure and its pattern symmetrical — the owner of that bulb had won the lottery. For the offsets of that bulb would inherit its pattern and hues and command a fantastic price. The fact that broken tulips for some unknown reason produced fewer and smaller offsets than ordinary tulips drove their prices still higher.

In an epoch when the microscope was still a novelty known to the very few and owned by the very privileged, when the discovery of submicroscopic non-bacterial pathogens was a quarter millennium away and the word ecology was two centuries from being coined, what the ardent gardeners and the ardent bulb-buyers and Rembrandt did not know was that a virus brought by another species was responsible for the rapturous breaking of the tulip; a virus the discovery of which vanquished the broken tulips and broke the spell their beauty had cast upon this ever-living, ever-dying world. Pollan explains the biomechanics behind the beauty:  The color of a tulip actually consists of two pigments working in concert — a base color that is always yellow or white and a second, laid-on color called an anthocyanin; the mix of these two hues determines the unitary color we see. The virus works by partially and irregularly suppressing the anthocyanin, thereby allowing a portion of the underlying color to show through. It wasn't until the 1920s, after the invention of the electron microscope, that scientists discovered the virus was being spread from tulip to tulip by Myzus persicae, the peach potato aphid. Peach trees were a common feature of seventeenth-century gardens. The color of a tulip actually consists of two pigments working in concert — a base color that is always yellow or white and a second, laid-on color called an anthocyanin; the mix of these two hues determines the unitary color we see. The virus works by partially and irregularly suppressing the anthocyanin, thereby allowing a portion of the underlying color to show through. It wasn't until the 1920s, after the invention of the electron microscope, that scientists discovered the virus was being spread from tulip to tulip by Myzus persicae, the peach potato aphid. Peach trees were a common feature of seventeenth-century gardens.

By the 1920s the Dutch regarded their tulips as commodities to trade rather than jewels to display, and since the virus weakened the bulbs it infected (the reason the offsets of broken tulips were so small and few in number), Dutch growers set about ridding their fields of the infection. Color breaks, when they did occur, were promptly destroyed, and a certain peculiar manifestation of natural beauty abruptly lost its claim on human affection.

Every time I think of the story of the broken tulip, I think of Richard Feynman's Ode to a Flower. Couple this fragment of Pollan's altogether enchanting The Botany of Desire with Emily Dickinson and the nonbinary botany of flowers, then revisit Sylvia Plath's almost unbearably beautiful poem "Tulips."

"There is nothing quite so tragic as a young cynic," Maya Angelou observed in her finest interview, "because it means the person has gone from knowing nothing to believing nothing." A decade earlier, in his 1967 Massey Lectures, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (January 15, 1929–April 4, 1968) examined the forces that dispirit the young into cynicism — that most puerile form of impatience — by mapping the three primary regions of reaction and resistance in the landscape of social change. Launched in 1961 by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and named after Vincent Massey — the first Canadian-born person to serve as governor general of Canada, who had spearheaded a royal commission for Canadian arts, letters, and sciences, producing the landmark Massey Report that led to the establishment of the National Library of Canada — the annual Massey Lectures invited a prominent scholar to deliver five half-hour talks along the vector of their passion and purpose, which were then broadcast on public radio each Thursday evening. Eventually, the CBC began publishing the lectures in book form. But some of the earliest ones, including the five Dr. King delivered in the final months of his life, remained unprinted for decades, until they were finally released in 2007 as The Lost Massey Lectures: Recovered Classics from Five Great Thinkers (public library).  Martin Luther King, Jr., 1964 (Photograph by Dick DeMarsico. Library of Congress.) In his third lecture, titled "Youth and Social Action," Dr. King presents a taxonomy of the three types of people into which the era's youth had been "splintered" — his own superb word-choice — by the era's social forces. More than half a century hence, it is a useful exercise, temporally sobering and culturally calibrating, to consider what the equivalents of these archetypes might be in our present time, in our present language. Our language might have changed dramatically — Dr. King was writing in the epoch before the invention of women, when "man" denoted all of humanity; an epoch when the acronym BIPOC would have drawn a blank stare at best and "Negro" was his term of choice — but we are still living with the underlying complexities which language always seeks to clarify and contain. The social forces splintering the present generation of youth have changed, and they have not changed — an eternal echo of Zadie Smith's observation that "progress is never permanent, will always be threatened, must be redoubled, restated and reimagined if it is to survive." With the caveat that the three principal groups sometimes overlap, Dr. King describes the first:  The largest group of young people is struggling to adapt itself to the prevailing values of society. Without much enthusiasm, they accept the system of government, the economic relations, the property system, and the social stratifications both engender. But even so, they are a profoundly troubled group, and are harsh critics of the status quo. The largest group of young people is struggling to adapt itself to the prevailing values of society. Without much enthusiasm, they accept the system of government, the economic relations, the property system, and the social stratifications both engender. But even so, they are a profoundly troubled group, and are harsh critics of the status quo.

It is easy to picture the young of our own time, roiling with the same restless ambivalence, the same resentful submission to the system, perched on their standing desks across the glassy campuses of Google and Facebook, drinking corporate kombucha on tap while composing impassioned tweets against police brutality, homophobia, and climate change, tender with the terror of being a person in the world, a budding person in a world that feels too immense and immovable. Dr. King captures this ambivalence with his characteristic compassionate curiosity:  In this largest group, social attitudes are not congealed or determined; they are fluid and searching. In this largest group, social attitudes are not congealed or determined; they are fluid and searching.

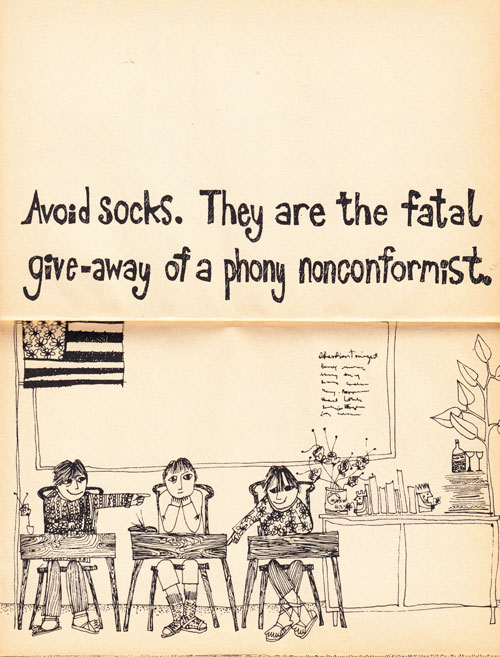

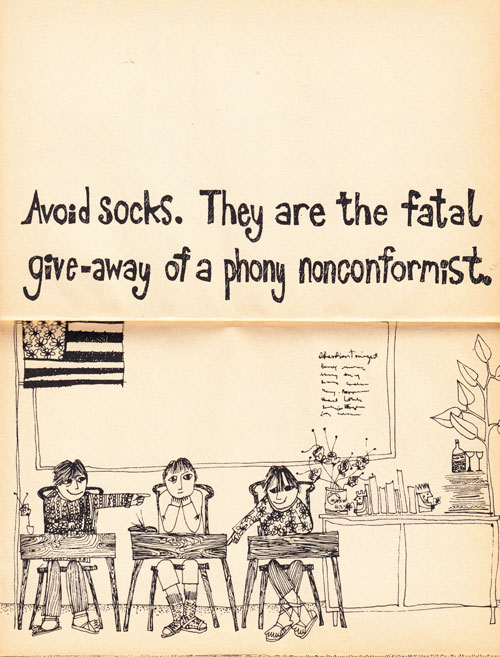

Illustration from How to Be a Nonconformist — a high school girl's 1968 satire of conformity-culture. He contrasts the first group with the second — those in outright and outspoken rejection of the status quo:  The radicals… range from moderate to extreme in the degree to which they want to alter the social system. All of them agree that only by structural change can current evils be eliminated, because the roots are in the system rather than in men or in faulty operation. These are a new breed of radicals. The radicals… range from moderate to extreme in the degree to which they want to alter the social system. All of them agree that only by structural change can current evils be eliminated, because the roots are in the system rather than in men or in faulty operation. These are a new breed of radicals.

This claim of novelty is somewhat ahistorical, or perhaps too narrowly American, for Dr. King's perceptive description of that generation's spirit is an equally apt description of the spirit of the generation that fueled the French Revolution two centuries earlier, an ocean apart. He sketches the radicals of the 1960s:  Very few adhere to any established ideology; some borrow from old doctrines of revolution; but practically all of them suspend judgment on what the form of a new society must be. They are in serious revolt against old values and have not yet concretely formulated the new ones. They are not repeating previous revolutionary doctrines; most of them have not even read the revolutionary classics. Ironically, their rebelliousness comes from having been frustrated in seeking change within the framework of the existing society. They tried to build racial equality, and met tenacious and vivacious opposition. They worked to end the Vietnam War, and experienced futility. So they seek a fresh start with new rules in a new order. Very few adhere to any established ideology; some borrow from old doctrines of revolution; but practically all of them suspend judgment on what the form of a new society must be. They are in serious revolt against old values and have not yet concretely formulated the new ones. They are not repeating previous revolutionary doctrines; most of them have not even read the revolutionary classics. Ironically, their rebelliousness comes from having been frustrated in seeking change within the framework of the existing society. They tried to build racial equality, and met tenacious and vivacious opposition. They worked to end the Vietnam War, and experienced futility. So they seek a fresh start with new rules in a new order.

In a sentiment that fully captures today's social media — that ever-protruding, ever-teetering platform for standing against rather than for things, a place increasingly unsatisfying and increasingly evocative of Bertrand Russell's century-old observation that "construction and destruction alike satisfy the will to power, but construction is more difficult as a rule, and therefore gives more satisfaction to the person who can achieve it" — Dr. King adds of these so-called radicals:  It is fair to say, though, that at present they know what they don't want rather than what they do want. It is fair to say, though, that at present they know what they don't want rather than what they do want.

Art by Ben Shahn from On Nonconformity, 1956. Identifying the third group as the era's "hippies" — a group the contemporary equivalent of which is especially interesting to identify and locate in our present generational landscape — he writes:  The hippies are not only colorful but complex; and in many respects their extreme conduct illuminates the negative effect of society's evils on sensitive young people. While there are variations, those who identify with this group have a common philosophy. The hippies are not only colorful but complex; and in many respects their extreme conduct illuminates the negative effect of society's evils on sensitive young people. While there are variations, those who identify with this group have a common philosophy.

They are struggling to disengage from society as their expression of their rejection of it. They disavow responsibility to organized society. Unlike the radicals, they are not seeking change, but flight. When occasionally they merge with a peace demonstration, it is not to better the political world, but to give expression to their own world. The hard-core hippy is a remarkable contradiction. He uses drugs to turn inward, away from reality, to find peace and security. Yet he advocates love as the highest human value — love, which can exist only in communication between people, and not in the total isolation of the individual.

Art by Corinna Luyken from The Tree in Me. In an especially insightful comment that applies to so many fleeting but vital and vitalizing movements across the sweep of history, he adds:  The importance of the hippies is not in their unconventional behavior, but in the fact that some hundreds of thousands of young people, in turning to a flight form reality, are expressing a profoundly discrediting judgment on the society they emerge from. The importance of the hippies is not in their unconventional behavior, but in the fact that some hundreds of thousands of young people, in turning to a flight form reality, are expressing a profoundly discrediting judgment on the society they emerge from.

He proffers a prediction substantiated by history, contouring the possible future of some of our own social movements when they have become another era's past:  It seems to me that hippies will not last long as a mass group. They cannot survive because there is no solution in escape. Some of them may persist by solidifying into a secular religious sect: their movement already has many such characteristics. We might see some of them establish utopian colonies, like the 17th and 18th century communities established by sects that profoundly opposed the existing order and its values. Those communities did not survive. But they were important to their contemporaries because their dream of social justice and human value continues as a dream of mankind. It seems to me that hippies will not last long as a mass group. They cannot survive because there is no solution in escape. Some of them may persist by solidifying into a secular religious sect: their movement already has many such characteristics. We might see some of them establish utopian colonies, like the 17th and 18th century communities established by sects that profoundly opposed the existing order and its values. Those communities did not survive. But they were important to their contemporaries because their dream of social justice and human value continues as a dream of mankind.

Art by Nahid Kazemi from Over the Rooftops, Under the Moon by JonArno Lawson. The most interesting challenge of applying Dr. King's taxonomy to our own time is that of seeing beyond the surface expressions that shimmer with the illusion of contrast, peering into the deeper similitudes between the attitudes of the past and those of the present. Escapism doesn't always look like escapism — escapism can masquerade as pseudo-engagement. A generation's drug of choice might be a psychoactive molecule, or it might be an intoxicating self-righteousness masquerading as wakefulness to difference. Technology might give the illusion of participatory action in democracy while effecting alienation at the deepest stratum of the soul — something especially true of the vast majority of pseudo-political uses of our so-called social media. Dr. King writes:  Nothing in our glittering technology can raise man to new heights, because material grown has been made an end in itself, and, in the absence of moral purpose, man himself becomes smaller as the works of man become bigger. Nothing in our glittering technology can raise man to new heights, because material grown has been made an end in itself, and, in the absence of moral purpose, man himself becomes smaller as the works of man become bigger.

Another distortion of the technological revolution is that instead of strengthening democracy… it has helped to eviscerate it. Gargantuan industry and government, woven into an intricate computerized mechanism, leaves the person outside… When an individual is no longer a true participant, when he no longer feels a sense of responsibility to his society, the content of democracy is emptied. When culture is degraded and vulgarity enthroned, when the social system does not build security but induces peril, inexorably the individual is impelled to pull away from a soulless society. This process produces alienation — perhaps the most pervasive and insidious development in contemporary society… Alienation should be foreign to the young. Growth requires connection and trust. Alienation is a form of living death. It is the acid of despair that dissolves society.

In consonance with the animating spirit of this here labor of love, he insists upon the importance of mining the collective record of experience we call history "for positive ingredients which have been there, but in relative obscurity." Echoing Whitman's gentle long-ago exhortation that "the past, the future, majesty, love — if they are vacant of you, you are vacant of them," Dr. King adds:  Against the exaltation of technology, there has always been a force struggling to respect higher values. None of the current evils rose without resistance, nor have they persisted without opposition. Against the exaltation of technology, there has always been a force struggling to respect higher values. None of the current evils rose without resistance, nor have they persisted without opposition.

Complement with Seamus Heaney's vivifying advice to the young, Kierkegaard on nonconformity and the power of the minority, and Richard Powers's antidote to cynicisms, then revisit Dr. King on the six pillars of resistance to the status quo. donating=lovingFor 15 years, I have been spending hundreds of hours and thousands of dollars each month to keep Brain Pickings going. It has remained free and ad-free and alive thanks to patronage from readers. I have no staff, no interns, no assistant — a thoroughly one-woman labor of love that is also my life and my livelihood. If this labor makes your life more livable in any way, please consider aiding its sustenance with a donation. Your support makes all the difference.monthly donationYou can become a Sustaining Patron with a recurring monthly donation of your choosing, between a cup of tea and a Brooklyn lunch. | | one-time donationOr you can become a Spontaneous Supporter with a one-time donation in any amount. |  | |  |

|

| Partial to Bitcoin? You can beam some bit-love my way: 197usDS6AsL9wDKxtGM6xaWjmR5ejgqem7 |

|

A SMALL, DELIGHTFUL SIDE PROJECT: AND: I WROTE A CHILDREN'S BOOK ABOUT SCIENCE AND LOVE | |

| |

Hello Reader! This is the weekly email digest of the daily online journal

Hello Reader! This is the weekly email digest of the daily online journal

you were searching through the hands of the monkey tree

you were searching through the hands of the monkey tree

No comments:

Post a Comment