| | | | | | | Presented By PhRMA | | | | Axios Science | | By Eileen Drage O'Reilly · Aug 25, 2022 | | Welcome back, science readers! - Alison Snyder returns from her sabbatical next week (yay!).

- Let me know your feedback as well as what topics you're most interested in.

Today's newsletter is 1,557 words, a 6-minute read. | | | | | | 1 big thing: Why explaining virus spread is a balancing act |  | | | Illustration: Maura Losch/Axios | | | | Public health messaging on both COVID and monkeypox has been too disjointed, confusing Americans on what steps they need to take to mitigate their risks. Between the lines: Viruses often have multiple routes of transmission, and educating the public on the likeliest route to infection can be a balancing act for officials who want to cover all their bases and have to account for unknowns and public mistrust, several experts tell Axios. Why it matters: The CDC and other public health agencies need to offer clear information on both potential and present risks that each outbreak poses and explain what they know — and don't know — before they lose more credibility. Context: It can take time to gather enough data to yield answers about how the majority of infections are happening, particularly when it's a novel pathogen, like Sars-CoV-2, which officials didn't immediately recognize as spreading asymptomatically — a fact that would have altered COVID guidance significantly. - "Oftentimes, you get a list of ways [the virus] can transmit, but there's a difference between how you list it in the textbook versus what's actually driving transmission," says Amesh Adalja, senior scholar for Johns Hopkins University's Center for Health Security.

- "There may be some very, very small chance of getting it a certain way in a certain circumstance — but is that actually behind how people are getting infected?" Adalja asks.

- For example, he says, monkeypox can be spread via surfaces, but "if we remove all the doorknobs from every door, will we still have a monkeypox problem? Yes."

Yes, but: The waiting period while data is gathered is a time when fear and misinformation can foment and people can start to take misguided actions. Misinformation about monkeypox appears to have spread faster than the virus itself. - This was also seen with the COVID-19 pandemic, where "the message got lost" that public health officials didn't know everything at the start, says Sarah Bauerle Bass, director of Temple University's Risk Communication Laboratory.

- "The messages seemingly just kept changing, and then [public health officials] lost that trust in the public's eye," Bass says.

- "You have to rate [behaviors] from the most risky to the least risky. Because it is possible to contract [monkeypox] from a surface or shared clothing or bedding. ... But, is it as risky as having close sexual contact with someone where you are skin-to-skin? No," she adds.

Respiratory viruses are the most vexing because it's hard to determine if the virus is airborne and can hover or transmit over distances, or if it can spread via aerosols that remain in the air for shorter distances. Plus, something that could be shown in a lab with animals may not be happening in the real world. - "You can infect a monkey with monkeypox in laboratory conditions by aerosol, but the epidemiology doesn't indicate that's how it's been primarily transmitted in the real world," says Angela Rasmussen, a virologist at the University of Saskatchewan's Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization.

- Another factor is that there are a limited number of institutions that can safely study airborne transmission of a virus, says Julie Fischer, microbiologist and senior technical adviser for CDGF Global.

The big picture: Three main ways to determine transmission are looking at "historical lines of evidence," "epidemiological evidence in the real world," and experimental evidence of potential avenues, Rasmussen says. - "But there's also the need to explain that risk is not binary. It's not that you're either not at risk or you're almost certainly going to get monkeypox. Everything exists in a shade of gray in between those two extremes."

Read the full story |     | | | | | | 2. Zoom in: What we know about monkeypox spread |  Data: CDC, U.S. Census; Chart: Erin Davis/Axios Visuals There are multiple transmission routes for a virus that's now in every state and has become a public health emergency. What's happening: While the majority of cases are concentrated among men who have sex with other men, there are signs of spillover into the general population, including to children. - This has led to concern that the virus is spreading via airborne particles, like COVID-19, or on surfaces, like smallpox.

While close bodily contact is the main risk, particularly via lesions that are thought to have high concentrations of viral DNA, "there is some evidence that monkeypox can be transmitted by droplet transmission," Fischer says. - People can transmit it by other means to household members, but that's not seen as a primary mechanism, Rasmussen says.

- As for close bodily contact, it's unknown "whether that's due to sexual transmission by semen or other body fluids, or whether that's just close skin-to-skin contact. It could be a combination of both," Rasmussen says.

Surface transmission, via shared bedding, clothing, or other objects, is also possible, but it doesn't appear to be a main transmission route, Rasmussen says. The CDC says it is researching if the virus can be spread via an asymptomatic person. - It's also looking at the role of respiratory secretions as well as if they can transmit via semen, vaginal fluids, urine or feces.

Read more and see Axios' Erin Davis' interactive map |     | | | | | | 3. Psychedelic may help with alcohol addiction |  | | | Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios | | | | Psilocybin from mushrooms combined with psychotherapy — a growing field of therapeutic research — may also help adults with alcohol use disorder, Axios' Tina Reed writes. What's new: Researchers found "robust decreases" in heavy drinking by adults diagnosed with alcohol dependence, per the small study published in JAMA Psychiatry. Details: The trial compared the effectiveness of 12 weeks of psychotherapy delivered with two day-long medication sessions of either psilocybin or an active placebo. - The 95 participants were adults diagnosed with alcohol dependence who had at least four heavy drinking days during the 30 days prior to screening but were not currently receiving treatment.

- During the seven-month period following the treatment, the percentage of heavy drinking days was 10% for the group that received psilocybin compared to 24% in the placebo group. The consumption of drinks per day was also lower in the psilocybin group.

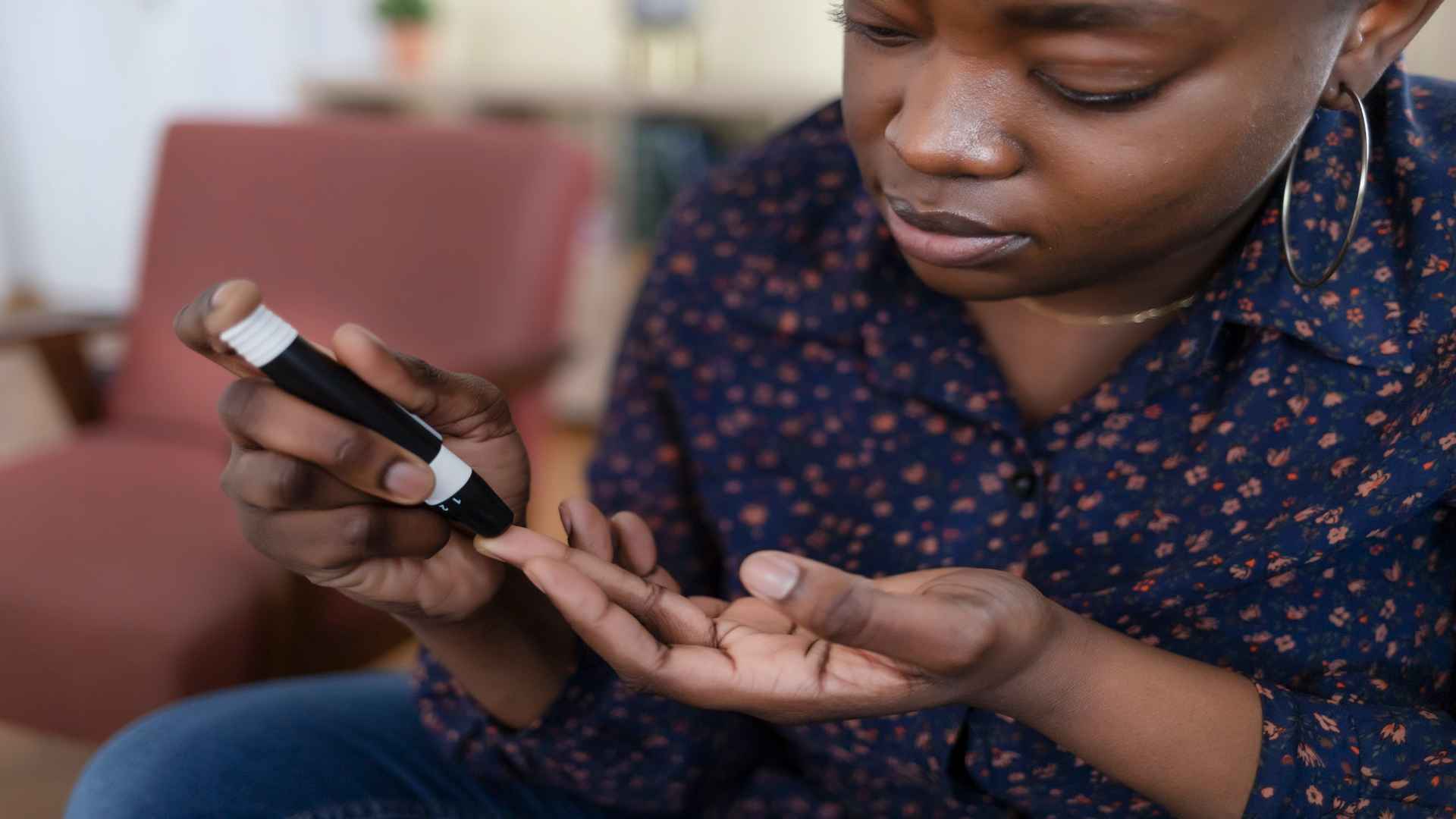

The bottom line: While further research is needed, it's a promising development for the understanding and treatment of alcohol abuse, which has few effective medication options, as well as for addictions more generally. Go deeper: Read the full story and check out Tina's newsletter, Axios Vitals. |     | | | | | | A message from PhRMA | | Improving access to life-saving medicine | | |  | | | | Insurance companies and PBMs don't pay full price for insulin. So why do patients? Rebates, discounts and other payments from manufacturers lower the cost of insulins by more than 80% on average — but insurers and PBMs usually don't share these discounts directly with patients. Stand up for patients. | | | | | | 4. What (threats) we're watching |  | | | California firefighters remove duff, or decomposing forest floor vegetation, in an effort this month to reduce fuels and decrease wildfire risk around giant sequoias. Photo: Mario Tama/Getty Images | | | | Valley fever: The invasive Coccidioides fungus that's been named a growing threat in the U.S. is endangering wildland firefighters in California when they don't wear respiratory protection and don't wet the ground before digging, the CDC weekly report warns. Polio: Scientists are on alert for polio, the highly contagious virus that can lead to permanent disability and death and has been found in New York and other countries, threatening a planned global eradication. Weather extremes: Areas around the world are reporting sometimes deadly weather events, including China's unprecedented heat wave and flooding in the U.S. Southwest. "Tomato flu": This very contagious but rare viral infection that's spreading in children in India could be a variant of foot-and-mouth disease. |     | | | | | | 5. What (advances) we're watching |  | | | Illustration: Rebecca Zisser/Axios | | | | Brain stimulation: Long-term memory was improved for up to a month after non-invasive, high-frequency electrical stimulation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex near the front of the brain, per a study in Nature Neuroscience. - Working memory was also boosted by stimulating the inferior parietal lobe, farther back in the brain, with low-frequency electrical currents.

- The technology, called tACS, holds potential, but many hurdles remain before this could be approved as a therapy, STAT writes.

Artemis: NASA's Space Launch System is expected to lift off Aug. 29, a move that will test whether the agency is "still on the cutting edge" of where it would need to be for human space exploration. Mini robot: A new robot called MiGriBot was 10x faster at micromanipulation than current models — potentially advancing microscale industrial assembly, per a study in Science Robotics. PFAS: Researchers may have discovered a way to get rid of toxic "forever chemicals," nearly 5,000 types of chemicals that resist degradation and are pervasive in drinking water. |     | | | | | | 6. Something wondrous |  | | | The galaxy NGC 7727 seen by the Very Large Telescope. Photo courtesy of the ESO | | | | About 1 billion years ago, two galaxies merged, creating a new galaxy seen in a photo taken by a telescope in the Southern Hemisphere, Axios' Miriam Kramer writes. Why it matters: Galaxies can grow and evolve through collisions like this one, giving scientists a glimpse into the diversity of these types of objects out there in the universe. What they found: The galaxy — called NGC 7727 — began to form when two galaxies danced around one another, disrupting their gas and dust, changing the way they each look. - The "tangled trails" in the photo taken by the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope were produced during the merger as stars and dust were stripped from their home galaxies and combined into one, the ESO said.

- "The core of NGC 7727 still consists of the original two galactic cores, each hosting a supermassive black hole," the ESO said in a statement. "Located about 89 million light-years away from Earth, in the constellation of Aquarius, this is the closest pair of supermassive black holes to us."

- The two black holes are about 1,600 light-years away from one another and will merge within 250 million years, producing a more massive black hole, the ESO added.

The big picture: The Milky Way is heading toward its own slow-speed cosmic collision with the Andromeda Galaxy billions of years from now, so learning more about these kinds of crashes could help scientists understand more about our own galaxy's future. Check out Miriam's weekly Axios Space newsletter. |     | | | | | | A message from PhRMA | | Health savings for patients, not middlemen | | |  | | | | Rebates and discounts from manufacturers lower the cost of insulins by more than 80% on average — but insurers and PBMs usually don't share these savings directly with patients. Next steps: Fix harmful insurance practices and lower out-of-pocket patient costs. Here's what you should know. | | | | Sign up here to receive this newsletter. |  | | Are you a fan of this email format? It's called Smart Brevity®. Over 300 orgs use it — in a tool called Axios HQ — to drive productivity with clearer workplace communications. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters. If you're interested in advertising, learn more here.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

Post a Comment

0Comments